Mapping No-Man’s Land: On Thomas Dilworth’s “David Jones: Engraver, Soldier, Painter, Poet”

Kevin McMahon praises “David Jones: Engraver, Soldier, Painter, Poet” by Thomas Dilworth.

By Kevin McMahonFebruary 8, 2018

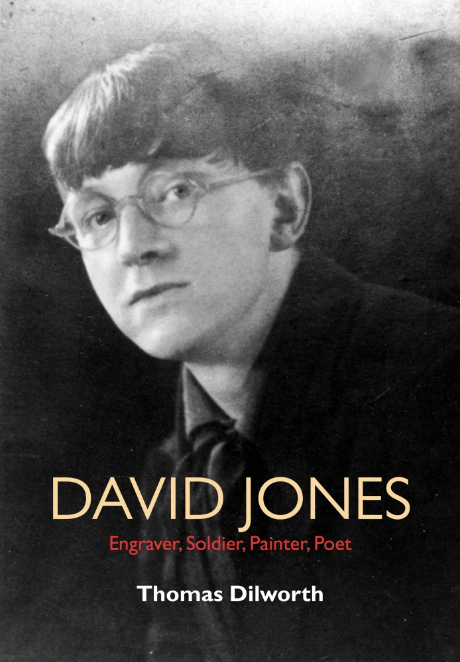

David Jones by Thomas Dilworth. Counterpoint. 448 pages.

IF THOMAS DILWORTH had chosen to arrange the material in his new biography of David Jones a bit differently, a big-budget biopic staring Daniel Radcliffe would already have been announced. All the necessary sensations are there: epic battles (Somme, Ypres), Eric Gill’s Jazz Age commune, serial unrequited infatuations, picturesque locales (Welsh countryside, Mandate-era Jerusalem, 18th-century country estates, squalid London rooming houses), villains (his dealer, his doctor), challenges (PTSD, agoraphobia, prescription meds), a heroic rally at the end, plus cameos by world-class scene-stealers like William Butler Yeats and the Queen Mother.

Moreover, Jones’s work itself is eminently cinematic, with his visual art (illustration, painting, drawing, painted inscriptions) being as important as the writing.

In fact, the time for a Jones biopic may be ripe. After all, the mythological deposits (his word) that he worked into his art also underlie some of the more prominent products of contemporary pop culture, even if Game of Thrones doesn’t explicitly credit Chrétien de Troyes. It serves to recall that Jones’s first book came out the same year as another saga of a journey to battle by another Anglo-Catholic veteran of the Somme enchanted by Anglo-Saxon war songs. The Hobbit might provide readers with a bridge to In Parenthesis (1937).

However, instead of maximizing sensation and sentiment, Dilworth has followed Jones’s own methodology of intense observation and jarring contrast.

¤

In Parenthesis provides the model. In a famous passage, Jones described the moment just before being blown up by artillery:

He looked straight at Sergeant Snell enquiringly — whose eyes changed queerly, who ducked in under the low entry. John Ball would have followed, but stood fixed and alone in the little yard — his senses highly alert, his body incapable of movement or response. The exact disposition of small things — the precise shapes of trees, the tilt of a bucket, the movement of a straw, the disappearing right boot of Sergeant Snell — all minute noises, separate and distinct, in a stillness charged through with some approaching violence — registered not by the ear nor any single faculty.

The juxtapositions of data, another term beloved by Jones, are the heart of his literary art. It makes it hard to introduce his work to people who haven’t read it, because individual phrases and passages don’t, on their own, give the real effect. For example, “Dai Greatcoat’s Boast” (from Part 4 of In Parenthesis) is everybody’s David Jones party piece. You can listen to recitations by Dylan Thomas and Michael Sheen on YouTube. Iain Bell’s 2016 opera of In Parenthesis made it an Act II showstopper. The grandeur is a neat dramatic effect: Jones inflates a soldier’s idiotic big talk into something truly extravagant, covering every conflict from Eden to now. But the real impact owes to the contrast with what comes before and what follows.

For example, a few pages before Dai Greatcoat’s outburst is an account of the soldiers being roused too early on a miserable morning. In the space of a few lines, it mixes material from a variety of deposits. It begins in the strong beats of Anglo-Saxon alliterative verse: “see their uneased bodies only newly clear; fearful to know afresh their ill condition; yet made glad for that rising, yet strain ears to the earliest note — should some prevenient bird make his kindly cry.” That is succeeded by tongue-tripping clipped precision: “Nothing was defined beyond where the ground steepened just in front, where the trip-wire graced its snare-barbs with tinselled moistnesses.” And this is answered, in counterpoint, by scraps of unfussy dialogue: “It hurts you in the bloody eyes, […] it makes you sneeze — christ how cold it is.”

Passages like this demonstrate the influence of traditional Welsh cerdd dafod (tongue craft). But Jones didn’t merely reproduce formal cynghanedd or englyn patterns of stress, quantity, alliteration, and rhyme. Instead, he was inspired to conduct similarly intricate but asymmetrical experiments in a great range of idioms: martial, profane, lyrical, and ecstatic.

Relating the story of this book and its author is challenge enough for any biographer, but Jones complicated things by his equally significant accomplishments in a different field. The same year In Parenthesis was published, Jones painted The Farm Door, one of dozens of pictures in a details-in-an-open-field style he developed eight years earlier. The conventional data of a pokey English barnyard are economically delineated: cows, flowers, chickens, and trees, as well as the interior from which they are presumably being viewed. Some are caricatures, some are careful portraits; some are elaborated in detail, others breezily sketched in. The relations between the cows, flowers, et cetera, and the interior fluctuate: the barnyard penetrates the walls, floors, and ceiling. Up and down, near and far are also muddled in washes of color. And the whole is bathed in a light that does not seem real. When summarized, this sounds like it might be the work of another modernist painter — Marc Chagall, Raoul Dufy, Pierre Bonnard — but in facture, detail, and tone it is utterly unique.

¤

Nobody alive knows more about David Jones than Thomas Dilworth. Moreover, he knows so much about his subject that he knows he doesn’t know everything. His biography offers a fair bit of interpretation and speculation, but he doesn’t assault readers with theories — he collates relevant data and organizes it in a chronicle, and he lets the stories speak for themselves. For example, he provides a concise account of the botched circumcision Jones received at 14, conveys the horror, then goes on to the next thing. He doesn’t make it an explanation of Jones’s life. Nor does he provide an essay about adult circumcision practices in the United Kingdom circa 1910.

The chronological organization permits Dilworth to spin out several different threads without bewildering the reader. The military thread, for example, first appears on page six, when five-year-old David watches with wonder as a recruitment parade for the Second Boer War passes by. “Who are they?” he asks his mother. “You’ll know soon enough,” she replies. It is picked up again, 15 years later, when Dilworth reproduces one of Jones’s first publications, a drawing of a resolute knight titled “Pro Patria.” It’s a polished piece and, in light of what’s to follow, darkly ironic. Its inclusion is an example of Dilworth’s insightful handling of Jones’s visual art: not merely Jones’s greatest hits, but significant works that also mark significant life events. The design (Rosie Palmer at Vintage) and physical production of the book — worthy of its subject, who first gained fame as an illustrator for editions de luxe — integrate words and images seamlessly.

By the time the reader arrives with Jones at the front, Dilworth has already chronicled his subject’s superior education in drawing, painting, and illustration, as well as his fascination with all things Welsh. Then, in quick succession, Dilworth recounts the milestones that permanently transformed Jones: arriving with the Royal Welch Fusiliers at the Somme in 1916, surviving the slaughter of a third of his comrades at Mametz Wood (chaos in which he almost shot his own commanding officer), receiving a bullet in the leg that prompts an orderly to exclaim, “What a beautiful blighty!”

While recuperating, Jones experienced his first crush, falling for a volunteer nurse named Elsie Hancock. Dilworth recounts it as leading nowhere, setting the pattern for Jones’s subsequent infatuations with Petra Gill, Prudence Pelham, Valerie Price, et al.

Jones’s return to the front (Ypres) was even more fateful. He was given a task more suited to his talents: map making. Dilworth’s insightful comment on the impact of this assignment is worth the price of the book:

Mapping no-man’s land since early 1916 intensified Jones’s spatial imagination in ways that would influence his art. […] His visual art of a decade later, and increasingly from then on, would consist of irregular areas of colour, wandering lines, and broken perspectives that give them affinity with maps.

The cartographic analogy applies equally well to Jones’s writings, where allusions to the Battle of Catraeth and King Pellam aren’t inserted to render the trenches romantically appealing, but to collects all the relevant data, without any of the corner-cutting or ignorant simplifications that Jones believed were stupefying and suffocating the modern world.

Early in 1917 Jones had two encounters that many would have instantly forgotten, but which fixed the map maker’s coordinates for the rest of his life. The first was a glimpse of a priest conducting mass at an improvised altar. The sight of the ancient rite conducted in the shipwreck of modernity sparked a line of thinking that led to his conversion to Catholicism four years later. “Jones did not become a Catholic to save his soul,” Dilworth writes, but rather, as Jones himself claimed, to “establish continuity with Antiquity.”

The second fateful encounter took place during a German bombardment. When Jones asked Leslie Poulter after their mutual friend Harry Cook, Poulter shouted back a punning quote from Henry IV, Part 1: “I SAW YOUNG HARRY WITH HIS BEAVER ON.” As Dilworth reports, “Poulter’s spontaneous allusion subsequently epitomised for Jones the penetration of the present by the past in the minds of infantrymen.”

This inspired Jones, for instance, to see his experience of service to the British Empire in the 20th century as a repetition of the experience of service to the Roman Empire in the first century. The motley assortments of men from all corners of their empires represented something more than imperial projects of unification and pacification of dubious legitimacy and practicality. Jones observed and projected back into Antiquity his own admiration of the rough and ready community of soldiers, united by grumbling, irony, and the struggle to get by. Dilworth recounts how, immediately after In Parenthesis, Jones began writing a new book, consisting of conversations between Roman legionnaires in Palestine and Wales, with bawdy/lyrical exchanges interrupted by pep talks from the officers. Jones worked on the project for seven years, but abandoned it, “hoping unity would emerge, but it had not.” Fragments of the work appeared decades later in The Sleeping Lord and Other Fragments (1974), and the posthumous The Roman Quarry and Other Sequences (1981). They’re electrifying.

Jones’s second book didn’t appear until 1952. Where In Parenthesis was a contemporary of The Hobbit, The Anathemata was a contemporary of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Klavierstücke. It concerns “inward continuities” and their reverberations through the ages, covering the whole pre-technological world from the standpoint of its almost-total extinction. It’s elliptical, dense, and allusive, and completely free of preening and swanking. These are not intimacies wrung from the heart, but artifacts unearthed from layers of sediment.

Dilworth often qualifies Jones as “native British” (as opposed to T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound), yet there’s nothing parochial about the man. The hierarchies of 20th-century British culture barely registered with him. In the 1960s, though needing the money, Jones declined a commission to design an inscription for the Prince of Wales. As a friend of his explained, he said no — “the last authentic prince of Wales died in 1282.” In general, Jones’s traditionalism was distinctly untraditional. For a religion- and myth-minded visionary, his work is free of revelations, last judgments, and miracles. Dilworth records his horror of mysticism and anything supernatural.

His taste was idiosyncratic and discriminating. He gave up on contemporary British poetry in the 1930s because of “its reversion to outdated conventional forms,” revered Finnegans Wake (1939) as the apex of modern literature and James Joyce as the model artist, but was generally more drawn to premodern works, like The Battle of Maldon. Yet even his antiquarianism was selective; he dismissed the most celebrated medieval Welsh poet, Dafydd ap Gwilym, as “brainless,” the Icelandic sagas as “curiously boring,” and Dante Alighieri as “power politics.”

Though much of his work echoes Rudyard Kipling, it’s free of chauvinism, reaction, and nationalism. As far as cultural authenticity and ethnic purity are concerned, Jones couldn’t have cared less. Quite the contrary: he delighted in hybridization. Catholicism, King Arthur, and ancient Wales were, for him, living — that is, still evolving — pan-European collaborations. Hence, his work frustrates any attempt to appropriate it for any parochial partisanship. For all his concern about preserving the Welsh language and traditional customs, nowhere does he advance anything like the romantic nationalism of, as he referred to it, “that horrible ‘Celtic twilight’ idea.”

¤

Dilworth also demonstrates that Jones’s openness was not merely intellectual. He rescues him from the suspicion that he was a spooky recluse. He may have been eccentric and agoraphobic, but he wasn’t isolated or lost in a visionary trance. In the 1930s, he mixed with most of the British modernist elite — T. S. Eliot, John Betjeman, and even Evelyn Waugh. He responded to fellow-creators as people, not as embodiments of ideologies. To a degree hard to credit in an artist or writer, Jones avoided both gossiping about colleagues and trashing their work.

The roll call of famous names continues throughout the book, all the way to the testimonials on the back cover, but Dilworth isn’t distracted by the glamour of vanished literary and artistic circles. He gives greater space to the people who were most significant in Jones’s life, such as his loyal patrons Helen Sutherland and Kenneth Clark, and a chain of non-celebrities who provided the man not only with friendship but with specific intellectual gifts: Thomism via Eric Gill’s circle; Jacques Maritain from his instructor in Catholic doctrine; T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922) from Tom Burns and the Chelsea circle; Joyce’s recording of the Anna Livia Plurabelle section from Finnegans Wake, thanks to René Hague; and W. F. Jackson Knight’s anthropological readings of Virgil from Harman Grisewood. Nicolete Gray’s appreciation of late Roman inscriptions as drawings inspired Jones’s most original work. The painted inscription designs that are, to steal a phrase from Lyn Hejinian, “words heard with the eyes.”

Dilworth knows that most readers won’t know the names he mentions, and glosses each with a neat phrase, as when he notes that Jones employed and befriended “Ethel Watts, the first female chartered accountant in Britain.” But Dilworth’s not about to pass up a good story. My favorite comes near the end. When the nuns at Jones’s nursing home urge him to tidy up for a visitor, Jones retorts with a bardic growl: “If you think I’m shaving for Kenneth Clark, I am not!”

¤

Dilworth ends his book with a summary evaluation of his subject: “A brilliant visual artist, the best modern native British poet, and the author of an original and convincing theory of culture” — in short, “the foremost native British modernist.” One of the first reviews (London Times) rebuked Dilworth for this misguided sentimentality, and sets the record straight, declaring that Jones’s poetry is — the glee is palpable — “rightly unloved.” Maybe that’s the case in the United Kingdom, but it isn’t true everywhere.

During the dark ages of the 1990s, when the AIDS crisis infected even the words and images directed against it, I found myself reading and rereading a used copy of In Parenthesis acquired years earlier as a curiosity. I didn’t care about the Royal Welch Fusiliers or World War I, but Private Ball’s encounter with a bomb and other disasters were presented with so little melodrama, such clear-sightedness, and such magnificent word-music that the book became a kind of life preserver. The book offers no consolation, but it affirms that empty rhetoric and melodrama do not permanently annihilate all serious thought and feeling. It also affirms that it is possible to survive being a survivor. In Parenthesis is not only an account of the ordeal of 1915 to 1918, but also of the ordeal of 1919 to 1937: the confused melee of recollection, pride, shame, sorrow, and second-guessing.

Jones always insisted that In Parenthesis wasn’t about the war, but about contemporary life: “We find ourselves privates in foot regiments. We search how we may see formal goodness in a life singularly inimical, hateful, to us.”

And so, his continued relevance is guaranteed.

¤

Kevin McMahon is a writer, scholar, and archivist based in Los Angeles.

LARB Contributor

Kevin McMahon is a writer, scholar, and archivist based in Los Angeles. He holds a bachelor’s in Classics from the University of Illinois and a master’s in Moving Image Archive Studies from UCLA. He has been the manager of SCI-Arc’s Kappe Library since 1987, and co-manager (with Reza Monahan) of the SCI-Arc Media Archive since 2012. His writing has appeared in a number of scholarly and popular journals.

LARB Staff Recommendations

When People Wanted Civilisation: Reassessing Kenneth Clark

Kevin McMahon appreciates the focus of “Kenneth Clark: Life, Art and Civilisation” by James Stourton.

Keith Douglas: A War Poet Remembered but Not Simplified

Steven L. Isenberg appreciates the vibrancy of Keith Douglas, Britain’s greatest poet of World War II.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!