Making It by Faking It

A new memoir about a youthful career as a fake classical violinist.

By Tucker CoombeMarch 11, 2019

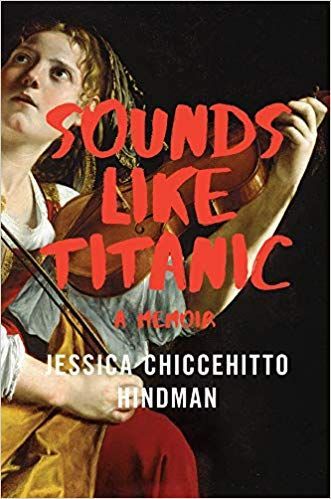

Sounds Like Titanic by Jessica Chiccehitto Hindman. W. W. Norton & Company. 256 pages.

TWENTY-THREE-YEAR-OLD JESSICA CHICCEHITTO HINDMAN, attired in long black dress, heels, and stockings, walks onto a stage at a New Hampshire craft fair. She takes her place alongside another violinist and a flutist. A dark-haired, lanky man — “The Composer,” as she refers to him — sits down at the piano. Projection screens on either side of the stage light up with images of an eagle swooping over the Grand Canyon, and the music — rich, satisfying, and strangely reminiscent of the theme song from the movie Titanic (1997) — begins. The audience is enthralled — entirely unaware that the musicians are playing in front of dead microphones, and that the music is emanating from a CD player purchased for $14.95 at Walmart.

Hindman’s debut, Sounds Like Titanic: A Memoir, recounts the nearly four years, beginning in 2002, that she spent working as a sham violinist for a nationally recognized American composer. By layering together scenes from her childhood in rural West Virginia, her time as an undergraduate at Columbia University, and the years she spent performing, Hindman strives “to get at the truth” of how she wound up where she did. Her memoir is original, funny, and deeply moving. It’s also perplexing. What caused Hindman, a young woman with obvious drive and intelligence, to settle for this farce of a career?

Hindman grew up in a dirt-poor town of 2,000. Her father was a family physician, her mother a social worker. At age four, after hearing a particularly haunting piece of music, she began begging for a violin. Four years later, her parents surprised her not just with an instrument but also with the promise of weekly lessons, which was no small gift. The nearest teacher was in the next state, and getting to and from the lessons — “over a half-dozen wheel-spinning, stomach-churning, ear-popping mountains” — routinely took anywhere from five to eight hours. These trips, Hindman writes, allowed “you to pretend, for at least a few hours, that you [were] not an eight-year-old girl wearing a pink ‘Almost Heaven: West Virginia’ t-shirt with a rainbow and unicorn on it, but [were] instead a serious adult person with serious adult person things to say.”

In adolescence, when the girls around her began falling prey to bullying boys and “drowning” in anorexia, “you [had] something tethering you to the shore,” she writes. “By putting a violin under your chin […] it [was] as if you [were] telling the world that you [had] authority on something, and in having this authority, you [were] more complex, more consequential than your young female body” suggested. Hindman’s insights into her childhood — the community she grew up in, as well as her own family — provide some of the most vivid and poignant passages in this memoir.

She enrolled at Columbia University in 1999, where every assumption she’d had about life was turned inside out. At home she had considered herself well off — she was, after all, a doctor’s daughter — but in New York, she viewed herself as “the only emissary of the Appalachian poor to the coastal rich.” Surrounded by classmates who had spent years studying at music conservatories, she was completely outclassed. Her violin professor, writes Hindman, “suggested that her time would be better spent hammering nails into her forehead than it would be teaching you how to play the violin.”

Hindman offers a harrowing account of a young woman whose ambition slowly gives way to desperation. In her first semester at Columbia, short of tuition money, she decided to sell her eggs at a Madison Avenue fertility clinic. But she wound up “on the cool tile floor of [the] dorm in a warm puddle of […] green vomit, a side effect of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome” — becoming so sick that she failed her midterms and missed earning a spot on the student orchestra, even as her roommate won the university’s concerto competition. In 2002, when Hindman was approaching her senior year, working two jobs but still not covering tuition, she spotted an advertisement for a professional violinist. She submitted a demo tape and — finally! some luck! — was offered a job with a traveling ensemble.

Much of Hindman’s time with this group was spent traveling through small towns as part of an ambitious 54-performance trip — the God Bless America Tour. The ensemble traveled in an increasingly dilapidated RV, stopping at locales so bland and faceless that she found herself checking the hotel phone book each morning to remind herself where she was. Hindman’s prose — even in describing barren, soulless towns — is lovely. Here, ruminating on how Walmart had changed the United States, the young Hindman gazed out the window at a Louisiana town that was “all but dead, its only pulse a skinny blue-vested teenager pushing a bumpy line of empty shopping carts toward the immaculate glass doors, which yawn[ed] open and swallow[ed] him whole.”

Threaded through her stories of life on the road are anecdotes about The Composer. (Hindman resists telling us his real name, but with a bit of detective work and help from Google, readers can come up with his likely identity.) He’s described with disdain early in the memoir — almost as if he were a caricature of a real person — but later depicted with surprising compassion. When he stood before an audience, Hindman tells us, his smile had such an intense, pasted-on “toothiness” that he reminded her of a velociraptor from the movie Jurassic Park (1993). He could not identify Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, and in all the years Hindman worked with him, he never learned her first name. He drove his musicians relentlessly, organizing performances at locales ranging from fairs and shopping malls — Hindman recounts performing at a 3:30 a.m. gig on the QVC home shopping network — to venues as prestigious as Carnegie Hall and the Shanghai Concert Hall in China.

But there’s something admirable about The Composer. His concerts raised millions of dollars for public television. His music — “thought by many to have curative properties,” Hindman tells us — had touched orphans in Africa and American soldiers stationed overseas. On the road with his ensemble, he insisted on staying after every performance to chat with members of his audience. Hindman shows us that, while he was undoubtedly a bit of a fraud, his knockoff music — combined with his ebullient presence — somehow lightened the load for thousands of Americans. If the performances weren’t entirely genuine, the joy they brought to people certainly was.

The concept of what’s real, what’s fake, and how one distinguishes between the two is raised throughout the memoir. “Notice,” Hindman writes, describing one of her performances, “that even though the music the audience [heard was] not being produced by you, the audience’s applause for you, their praise, their standing ovations, [were] real.” The adulation, far from seeming inconsequential, felt like “an additional form of currency in which you were being paid.” One has to wonder whether the young Hindman was genuinely incapable of telling real from fake, or whether — just perhaps — she so yearned for praise that she gratefully accepted applause she knew to be undeserved.

It’s clear, however, that the work took its toll. After a couple of years with the ensemble, she started experiencing mysterious panic attacks during performances — “the opening notes of a disorder that [would] mar the upcoming years so completely that your life [would] become unrecognizable.” But, for reasons never quite specified, she remained with the group.

The author holds herself accountable for some of her problems and bad decisions — her parents had “begged [her] to turn down Columbia,” she tells us, but she’d insisted on going anyway. At the same time, she describes a world where vague forces seemed aligned against her, with one crisis paving the way for the next. Because of the exorbitant cost of college, for example, she had to work three jobs to cover tuition. Since one of these jobs — traveling with the ensemble — required working long weekends, she was forced to squeeze a full week’s worth of academic work — plus her two other jobs — into four days. Because she was perpetually exhausted, she turned to cigarettes and coffee, and because they didn’t do the trick, she ramped up to Adderall and cocaine. She visited Columbia’s mental health clinic in search of help, but because the counselor got distracted by her West Virginia childhood (“You actually grew up there? Like with cows?”), she was left to sort things out, once again, on her own.

A reader could be forgiven for finishing this memoir and asking, “Did I miss something?” Why did Hindman finally leave the ensemble? The author explains only that, after being diagnosed with a “debilitating psychiatric condition,” she needed a job with health insurance. She worked a couple of demoralizing occupations. And today she’s a college writing professor. How did she get from there to here?

Late in the memoir, as she reflects on her days with the ensemble, Hindman recalls watching a TV show from her childhood, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, and listening to Rogers talk about the importance of make-believe: “It helps to play about things. It helps you to know how it really feels,” he tells his audience. Working as a fake violinist, Hindman claims, taught her “what it would feel like to be an actual, real, world-class musician.” Is Hindman truly suggesting that child’s play translates into carte blanche for a life of fakery? One wonders whether she’s letting herself off the hook a bit too easily.

Hindman is never fully forthcoming about what attracted her to the work, or what allowed her, finally, to choose a new path. Throughout the book, she makes penetrating observations about the people around her — angst-ridden high school girls, smug college students, even her colleagues in the ensemble. And she frequently writes of her young self with raw, searing honesty — even when, as shown from the quotations above, she persistently couches her self-analysis in the second person. Yet her small, but critical, omissions weaken what is otherwise a brave and captivating memoir.

¤

Tucker Coombe writes about nature and education. She lives in Cincinnati.

LARB Contributor

Tucker Coombe writes about nature and education. She lives in Cincinnati. You can find more of her work at tuckercoombe.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Bach at the Burger King

When the music of Vivaldi and Mozart are used to repel the homeless from sidewalks and Burger Kings, does it still glorify the dignity of humanity?

Who Sings the Revolution?: On Julia Balén’s “A Queerly Joyful Noise: Choral Musicking for Social Justice”

Morgan Woolsey wrangles with the political potential of queer singing in Julia Balén’s “A Queerly Joyful Noise: Choral Musicking for Social Justice.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!