The Magic of the Everyday: An Interview with Kelly Luce

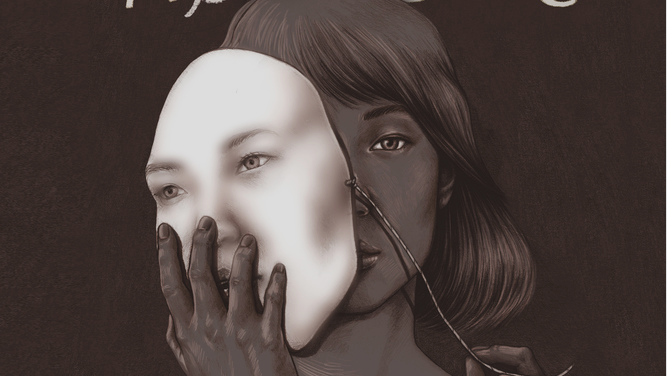

R. O. Kwon talks to Kelly Luce about karaoke, the limits of magical realism, and Luces's new novel, "Pull Me Under."

By R. O. KwonJanuary 6, 2017

I FIRST ENCOUNTERED Kelly Luce’s writing in 2013, with the publication of her debut story collection, Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail. The book was published by what was then a new press, Austin-based A Strange Object, founded by Jill Meyers and Callie Collins. I’d trusted their taste for years, and I was delighted by Luce’s stories, which mixed surreal inventions — death-predicting toast, a life-changing karaoke machine — with emotional truths.

Luce just published her first novel, Pull Me Under (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). In it, she explores a differently surreal condition: childhood, and the way it shapes our eventual adult selves. The protagonist of the novel is Chizuru Akitani, a sixth-grade girl in Japan who is tormented by a bullying classmate. She eventually stabs and kills her bully. The rest of the book follows Chizuru, now known as Rio, as she grows up and lives with the repercussions of her act.

¤

R. O. KWON: What led you to telling this story about a biracial girl in Japan who kills her bully?

KELLY LUCE: Going back to the beginning: I lived in Japan for a few years and while I was there, I taught in public junior high schools for a while. While I was at that job, I learned about this phenomenon in Japan known as kireru — which means “to cut” or “to snap.” It was, and still is, this phenomenon of young children, often under 14, committing violent acts for seemingly no reason. Kids who were otherwise well behaved, got good grades, didn’t make waves. There was a boy who beheaded a classmate in the next prefecture when I was there. He was the same age — seventh grade — as the kids I was teaching.

Oh, god.

Another aspect of this phenomenon that caught my attention was that it happened with female students, too. You think of kids “snapping” in western culture, and you think Columbine, et cetera. In the West, it’s always men. (And it’s usually guns, but that’s another conversation!) It became this question for me, as a person interacting with kids in Japan who were this age on a daily basis. What would make a kid do this? Why does this happen in Japan, a relatively crime-free and peaceful country, and nowhere else? And by nowhere else, I’m referring to the male/female ratio of violent outbursts, and the young age at which kireru attacks often happen.

That’s where Rio came from. She’s biracial, haafu, which in Japan can and often does make one an outsider. Just look at the recent news of the backlash to the new Miss Japan, who has an Indian parent, and Ariana Miyamoto before her [a Miss Universe winner, whose father is African-American] — a lot of backlash with regards to purity of blood being part of what makes a “true Japanese.” I witnessed mixed-race kids in my schools bullied in subtle ways as well. I imagined there would be a lot of anger in a child who always felt “half” and never whole.

I’m curious about the slow unveiling of the central kireru scene, when Rio kills her bully. You keep going back to it, spiraling around it. There’s narrative suspense! How did you think about releasing information?

I reluctantly realized that the book was not truly about the events of Chizuru or Rio’s childhood. The real story was Rio as an adult, living with this in her past, so that’s how the novel is framed and paced. But we needed to see what led up to Chizuru committing this act. So I wrote those episodes leading up to the stabbing — the escalating bullying, the details of what’s going on in her home life — and then found that they actually naturally fit into the present action of the novel as brief flashbacks.

I experimented with dropping them into various parts of the present action. I remember well the advice of an early writing teacher, John Dufresne: only jump into a flashback if the flashback is more interesting than the present moment. Get out, and back to the present, as soon as you can. I tried to get the flashbacks and the present action to come to a head around the same time. Though that isn’t something you can force.

What do you mean by that — it isn’t something you can force?

I mean imposing structure on a novel. Trying to force two threads to weave perfectly together. It’s zoomed-out in intention; I think readers can feel that and will call bullshit. Forced elegance feels weird. I don’t want my novel to be prom. I want it to be a messy, ecstatic dance party in a barn.

I first came across your writing with your story collection, Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail. Your novel is very different from the collection, especially in its swerve away from the magical-realist elements in Hana Sasaki. Was that an early choice, or did you just find that fortune-telling toasters had no place in the novel?

I actually dislike all these terms and think they’re misleading, but, yes, I knew from the beginning this wasn’t going to be a novel with magical-realist or traditionally speculative elements. The idea — that question about character and motivation I mentioned earlier — was the seed for the book. It was obvious that it had nothing to do with psychic appliances or talking coins. That collection doesn’t have magic in every story, either.

I also think it’s really hard to carry a magical-realist conceit through a whole novel, at least for me. There was so much that was surreal about Rio’s story, there was no need for anything else. It would’ve been gauche and undermined the whole thing. It never crossed my mind. So much of what drives my writing is the magic of the everyday, which I think is present in spades both in Hana Sasaki and in this novel.

That maybe sounds corny but I’m really interested in how far belief can carry people.

Is there a part of writing you find especially satisfying, something that makes you think, “Damn, this is why I got into this.” Or maybe you have many parts? Or all of it might be like that for you …

[Laughs.] All of it, I wish! Writing is mostly mental torture, because it takes all my energy to dig deep and find the words, the combination of sentences, the scenes, to express something that there aren’t words for. I feel like Whoopi Goldberg when she’s acting as a medium in Ghost: I’m using all my energy to try and get there. The best part is when I find myself typing something I love, and I never knew I thought it before I wrote it.

The act — the physical act — of writing is one of discovery, and it can be incredibly satisfying to put words to a feeling or experience. Words you can look back on forever and say: that’s how it was. And you know that other people, at least some other people, will read it and recognize it and get something from it, too.

I’m not religious, but I always think of writing as a practice of faith. It’s a small miracle, or at least a moment of grace, when you get it right, and that moment is priceless.

I grew up very religious — though I’m not at all religious anymore — and writing, at its best, can feel not unlike worship at its best. Faith falters, though. When you get stuck writing, what do you turn to for help?

That’s tricky to answer, because I’m always thinking about what I’m working on. I don’t write linearly, from start to finish, so I can always just write a scene I know, or think I know. When I’m stuck in terms of decision-making, like, “What should happen to this character? What kind of ending is this story asking for?” I try to let my gut guide me into reading things that will help me answer those questions. I also listen to music. I try to turn my body into a tuning fork for the story.

Of course I also revise constantly, so if I don’t have anything I’m confident writing fresh, I revise raw stuff I’ve already written, and the act of revision takes me a layer or two deeper, and sometimes opens doors. I also like to reread favorite poems and stories. I get in trouble for not reading the new stuff because I like to read my old favorites a zillion times. It reminds me that it’s possible, you know? That powerful, moving writing is possible to create.

What are some of your old favorites?

When I need to be reminded that straightforward, fairly simple language can produce tremendous emotional effects, I read Kawabata’s Palm-of-the-Hand Stories, “The Grasshopper and the Bell Cricket” in particular. And any number of Stuart Dybek stories, or Lois Lowry’s The Giver.

If I want to remember how it feels to be explosively in love (and who doesn’t), I read Nico Alvarado’s “Tim Riggins Speaks of Waterfalls” (seriously, it’s hot), or Muriel Rukeyser’s “Looking at Each Other,” or “Did It Ever Occur to You That Maybe You’re Falling in Love?” by Ailish Hopper. Stephen Dobyns’s “How to Like It” is one of my favorite poems ever. I could go on but I’ll stop there.

Speaking of Tim Riggins, I was just rewatching a bit of Friday Night Lights last night and crying, because that’s what happens anytime I watch that thing.

Oh, my god, I am just watching FNL for the first time ever, right now. I’m on season three.

Oh, sweet lord.

I read Nico Alvarado’s Tim Riggins poems before I even saw the show! They are why I downloaded it. [Laughs.] I’m the first person to ever watch network television because of a poetry chapbook.

Your prose in Pull Me Under is very natural, and could be described as straightforward, fairly simple. I liked that about the novel, and I was wondering if you read out loud while you write.

Not while I write, no, though I hear the words in my head. I read aloud when I revise. It helps me notice what rhythms and words I’m overusing. I have a list.

A list! Would you be willing to share any part of it?

Yes … off the top of my head, I need to search manuscripts for “then,” “after all,” “though,” “seems,” “almost,” “somehow,” “slightly,” and “bright.”

My editor also noticed that I invoked blueberries far more than is reasonable in one draft of the novel. “Just.” I’m an editor, and I adore cutting words. It’s very satisfying. People hate revision, but I think it’s the most fun part of writing other than the epiphanies we talked about earlier.

You edit for Electric Literature. I’m always impressed by people who can both write and edit: how do you balance the two?

I’ve always done freelance editing to make a living. I enjoy working with clients who are, by and large, professionals in other fields, and who just wanted to write a novel to try it out. Those clients have a lot of fun writing, and have no real ego about it, which is refreshing. As for the literary magazine editing work, I guess the way I think of it is, editing creates balance in my writing life.

Doing my own writing is an internal struggle, going inside myself. Editing is an opening up. I love working with writers who often have such different life experiences and worldviews from myself. We’re working together to make sure they tell their story as best they can. It can be tough to be behind a screen all day, though. Some days I go to the post office and forget how to speak to the person behind the counter because I’ve been in my head for a full day or two.

You studied cognitive science in college. I often think there isn’t enough good fiction with science in it, or math, and I enjoyed Rio’s flourishes of medical knowledge. Did you ever think you’d become a scientist?

Yes, I wanted to be an astronomer, then a physicist, and I took those classes. Then I found cog sci, which was asking the questions I was most interested in: How do brains work? And emotion? What makes people people? I got really into music cognition, in particular the way the brain processes emotion with regard to autobiographical memory and those “special songs” that can transport us with two notes.

While I was interested in the questions cog sci was asking, I found I was a shitty scientist! I got this wonderful grant from Northwestern to run an experiment on music and emotion and memory, and we did it, the results were pretty good, but I remember thinking the whole time: if only the results were more like this, or this participant had said that, it would make a better story. Key words being: Make a better story. I love science, but what I’m most interested in is stories, and I will always fudge the facts to make you cry. Science and writing are both ways to get to truth; I just feel like I can get there faster with fiction.

You also studied music, which is central to this book. We’ve talked in the past about a shared love of karaoke: What are your go-to songs? Do you prefer private-room or public karaoke?

[Laughs.] I love this question! Okay, first of all, definitely private box. As for go-to songs, it depends on the crowd. In Japan, I would go to the karaoke box alone and sing for hours, and I would sing the cheesy songs I’d loved as a teenager: Mariah Carey, Céline Dion, that kind of stuff. With a group, I try to make it fun. I like to rap to Ludacris’s “Area Codes,” or Snoop Dogg. If someone wants a duet, I’ll go “Jackson” or “Paradise by the Dashboard Light.”

I’ll sing pretty much anything.

¤

LARB Contributor

R. O. Kwon’s first novel, Heroics, is forthcoming from Riverhead. She is a 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellow, and her writing has been published in NOON, the Guardian, VICE, Ploughshares, the Believer, Tin House, and elsewhere.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Ways of Seeing Japan: Roland Barthes’s Tokyo, 50 Years Later

Colin Marshall looks back on Roland Barthes’s look at Japan in “Empire of Signs.”

Susan Bernofsky Walks the Tightrope: An Interview About Translating Yoko Tawada’s “Memoirs of a Polar Bear”

Stefanie Sobelle talks to Susan Bernofsky about translating Yoko Tawada's new novel as well as works by Kafka, Hesse, and Robert Walser.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!