“Madonna Was My Sex-Ed Teacher”: A Conversation with R/B Mertz

Samantha Mann talks with R/B Mertz about their memoir, “Burning Butch.”

By Samantha MannAugust 25, 2022

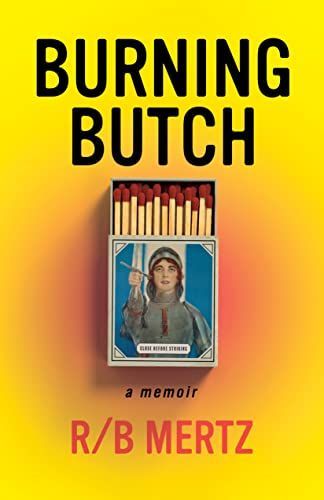

Burning Butch by R/B Mertz. The Unnamed Press. 392 pages.

NOTHING WARMS THE HEART of my inner child more than reading accounts like R/B Mertz’s memoir Burning Butch, which highlights a queer childhood. Mertz grew up homeschooled in a cultlike Catholic atmosphere while I grew up a reformed Jew, but despite these differences, we both carried a feeling of otherness that made us feel more like spectators than participants during our adolescent years. This early proclivity for observation is true of many queer folks, which is maybe why so many of us are interested in the arts. As well as documenting the struggles of closeted queerness, Mertz’s book vividly highlights the cultural refuges young queers often turn to — such as show tunes and Madonna.

In Burning Butch, Mertz fearlessly faces the ugly aspects of their past, including religious trauma and incest. From their perspective growing up in extreme Catholicism, Mertz’s memoir urges us all, no matter our background, to examine our own upbringings, reflecting and deciding what from our past we should carry into our future and what we should leave behind. This call for reexamination makes Burning Butch a book for all memoir lovers, not just the queer community.

I recently had the pleasure of chatting with R/B about their writing process, sex education à la Madonna, and why they think Broadway is so affecting for young queer folks.

¤

SAMANTHA MANN: Congratulations on this gorgeous and complex memoir. When did you start writing the book, and how do you feel it turned out compared to how you originally thought it would be?

R/B MERTZ: I started writing this book about 10 years ago. It was slow going because it was intense content to write about. I had to have space to have a terrible 24 hours after writing, so that made the process slow. I always wanted a book that was written in short sections and spurts because I thought of them as poems. And I wanted it to be not just about one challenging context of my life, but about everything. I think I did that.

I was impressed by how much varied content you put into this book. So often in publishing you’re only allowed to have one standout idea, like you can be a dyke who was assaulted, or you can have escaped a religious cult, or you can engage in self-harm, but you can’t have them all. This seems especially true with the big publishers.

I’m not surprised I found a home in independent publishing with Unnamed Press. All my heroes are independent artists and people whom the institutions rejected.

I realized reading your book that I hadn’t understood how pervasive religious trauma is in our country. As someone who grew up with this experience, how do you think you were kept isolated from the secular world so intensely and for so long?

I think the goal of those religious groups is to take over your imagination so that you’re not supposed to think about stuff outside of their teachings. These religious narratives are very gaslighting and it becomes confusing to think outside of them.

Reading about you “protesting” at the abortion clinics was powerful. It was the first time I realized that some extremely religious folks are children who have been swept up into this movement without any say. As someone who spends a lot of time thinking about other people’s points of view, I was shocked that I had never given this particular group of people the benefit of the doubt.

It’s not easy to have empathy for people in a group like the Westboro Baptist Church, who have public messages like God hates fags. My group was communicating those messages, but not being so black-and-white about it. I think empathy is about who we have context for and who we have the ability to see the whole story of.

Most of the queer adults I know found comfort in show tunes and Madonna. What was powerful to you about Madonna, and why do you think show tunes and theater are such a pull for queer kids?

Madonna was my sex-ed teacher. In homeschooling, there’s a habit to make a class out of everything, like if you went for a nature walk, that was gym class and science class. I was constantly seeking out Madge content and learning things like what a dildo was, what a blowjob was, and HIV awareness. I never got my hands on the sex book, but her interviews were very educational.

For show tunes, I think there’s something queer about bursting into song. The character is having a silent thought that is actually also a huge song performed by a crew of dancers and an orchestra. They’re singing loudly, in a big public space surrounded by others. But it’s supposed to be just this private moment. I think it’s this internal-external sort of explosion.

Alisson Wood wrote a memoir, Being Lolita, about how a high school teacher groomed her in part by using the novel Lolita. I was shocked reading your book to see how an adult man on the internet also attempted to use Lolita as part of what seemed like a grooming process. The idea of using art to groom children is so disturbing. Wood has said that since she published her book, the number of women who have reported to her about assault, rape, and inappropriate relationships with their teachers has been beyond what she ever imagined. As a professor yourself, how do you now perceive the way faculty inappropriately interacted with you? There were so many boundaries crossed at your college.

I’m waiting for more of a watershed moment to happen with schools and colleges. We know that it’s happening. I have several friends who were abused on various levels by teachers, male and female. I really wish we would stop pretending that women don’t commit sexual crimes, because they commit them against men, women, and gender nonbinary people. I don’t think there’s anywhere or any type of relationship where this abuse is not occurring.

In her book When I Spoke in Tongues, which is about growing up in a Pentecostal church, Jessica Wilbanks wrote about how she desperately wanted to speak in tongues like people in her church. In your book, when you encountered people speaking in tongues, you seemed turned off by it, which was surprising because you believed in so much of what was taught to you. Why do you think this was not of interest to you?

It made me uncomfortable. Maybe because I encountered it when I was older. It felt performative when I first encountered it, and even amidst that, I knew these were sincere people. It wasn’t something that I aspired to.

In the book, you touch on how difficult it is to separate art from artists. Right now, a lot of people are trying to decide what to do with their favorite art as they find out more heinous information about the artists. I’ve had friends tell me they aren’t going to listen to Michael Jackson anymore, which I think is appropriate and someone’s personal choice. But then I think, because of his enormous impact on pop music, we can’t just erase Michael Jackson. It’s not easy and there are no good answers, but where are you in terms of choosing what to consume?

That’s a hard one for me. I’m at the place where I cannot judge anybody’s kind of consumption of art. What you want to watch or listen to or read in that moment is something I don’t understand — I don’t understand why those impulses occur in myself, why I want to read something versus another thing. For individual people and what art they’re into, I think that’s too complicated to judge.

I will say, for teaching, that I’m not recommending William Faulkner because he uses the N-word, and I’m not passing on a book that will trigger my students. I want to learn about novels, but it’s not like William Faulkner is the only writer to learn from. Same for film: Woody Allen did cool stuff, but I think there are other movies we can learn from. We’ll be fine without Manhattan and most of Annie Hall. Actually, I do think some of Annie Hall should be on a spaceship somewhere, but that’s it.

What are your hopes for this book?

I just want lots of people to read it. I think it would make a great movie. I really want people to take it seriously, not just as a queer book. That’s been the area where I’ve been receiving praise and coverage, which is really lovely and wonderful, but I also wrote it understanding that non-queer people read books and want to understand things too.

I think it’s a universal book. It’s about how you have to reconcile the information and the culture that you grew up in with the culture of everywhere else, the fact that your parents don’t know everything, that your experience has been limited, and now you have to decide who to be. I don’t think you have to be in a religious cult to grow up with the experience of other people wanting you to be a certain way, and wanting you to do certain things and not do other things.

I was really trying to write about the experience of what that does, especially when the expectations of your culture are violating you or are perpetuating violence against you through abuse. The more we do the work of asking What do I think? Who am I? What do I want? I think we can know we’re going to do less harm. We’re going to do less unconscious harm if we’re really interrogating who we are and thinking about other people [as being] as complex as us, as interesting as us, and as mysterious as us. It’s a lot harder to hate them, and it’s a lot harder to say they don’t matter.

Recently, I was talking with a friend, and we were wondering about young queer people today. I live in Brooklyn, and it seems like all the kids here are queer. We were joking and wondering what will happen to art if all these queer kids grow up loved and appreciated just as they are?

If I had not grown up the way I had, if I had grown up, for lack of a better word, in a less traumatizing situation, I think I would have still made art. I think the children will paint beautiful things, write beautiful poems, and be able to be human beings who might get to be more joyful. They’ll still have feelings like falling in love with the wrong people and getting their hearts broken. They will be running around doing terrible things and they’ll get sad about it, so I think art will be okay.

I love your positivity. That’s a nice note to end on. Thanks, Mertz.

¤

LARB Contributor

Samantha Mann is the editor of the anthology I Feel Love: Notes on Queer Joy (Read Furiously Publishing, 2022). She is the author of Putting Out: Essays on Otherness (Read Furiously Publishing, 2019).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Widow’s Peak

Laura Mauldin explores long and intensive caregiving, the devastation of losing a partner, and the process of healing, in part through having and...

Writing Toward Communal Responsibility: A Conversation with Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore

In “The Freezer Door,” Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore questions everything.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!