How About Love: Gilbert Hernandez’s "Julio’s Day"

Anne Elizabeth Moore offers a frank review of Gilbert Hernandez’s Julio’s Day and a little love, too.

By Anne Elizabeth MooreFebruary 28, 2014

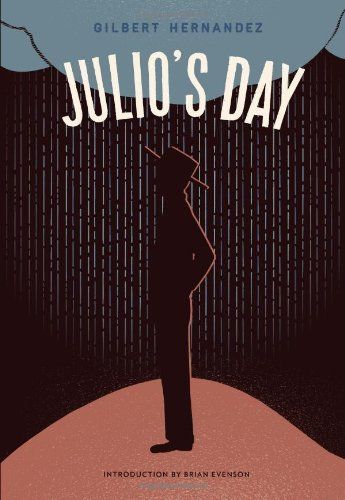

Julio's Day by Gilbert Hernandez. Fantagraphics. 112 pages.

Five hundred twenty-five thousand six hundred minutes

How do you measure, measure a year?

In daylights, in sunsets

In midnights, in cups of coffee

In inches, in miles, in laughter, in strife

In five hundred twenty-five thousand six hundred minutes

How do you measure, a year in the life?

How about love?

MUCH OF THE HUBBUB around Gilbert Hernandez’s Julio’s Day seems intent to convince you, the reader, to place the book on that high, dusty shelf of literary genius — between Samuel Beckett and Gabriel García Márquez and, yay! Junot Díaz has even blurbed it! — but let’s back away from such extolations for a moment. This is, after all, comics, an oft-maligned form deeply beloved by only a certain number of people and noticed occasionally by others, usually when there’s a new superhero movie out, although they may be unable to distinguish Beto’s impressionistic line work from brother Jaime’s starker forms, sad as that may be. And while the Hernandez Brothers, Los Bros, have done more to develop narrative nuance, long-term character study, and graphic stylization than any creators working today — the hallmarks of what we might consider literariness in comics — I’m not sure that particular praise is apt.

In truth, comics have far more in common with your average Broadway musical. The marginalization of devoted adherents within larger culture, the vociferousness of their passions. Costumes. Brian Evenson’s introduction to Julio’s Day offers an epigram from Waiting for Godot’s blind and cruelly manipulative antagonist Pozzo:

[…] one day we were born, one day we shall die, the same day, the same second, is that not enough for you?

But it is within the Broadway musical genre that I find a much the better-fitting epigram above, in “Seasons of Love,” from Rent.

You will recall that the La Bohème rip-off, recast as a Broadway-ready musical by Jonathan Larson in 1996, gained renown when Larson died of heart failure the night before the Off Broadway premiere. Luckily the thing actually was Broadway-ready: it moved there to prosper three months later, eventually grossing $280 million and outlasting the AIDS crisis it sought to sensationalize. The story concerns a group of artsy friends of diverse racial, sexual, and gender identities, who sometimes have sex together, and sing a lot, and deal with issues of not having health insurance while HIV positive and paying rent. The constant specter — and presence — of death amid such frenetic vibrancy leads to tuneful soul-searching. And here is the pressing question the group explores, posed overly catchily in the song, that Julio’s Day answers in full: What value a year within the span of a life? And what value, therefore, that life at all?

Can it be measured, the lyrics question, “In truths that she learned, or in times that he cried? / In bridges he burned, or the way that she died?” Yes, it’s sappy — cartoony, maybe? — but how else to get to the over-made point that, despite all the hokiness and the downright laughability of it, maybe the value of a life is to be found in the people you invested in and cared for, shielded from harm or simmered at in rage. Maybe the only way to measure a year, or 10 years, or, hell, even 100 years is through the banal and silly and effed up and truly devoted folks that surrounded someone, and were loved.

Julio’s Day is a 100-page story of a 100-year-old man’s life spread over all of those 100 years. It is also the story of the entire 20th century, the world, a nation, a small Southern town in the United States, a family, and a single man’s negligible impact over all this. Unless you measure in love.

Less important than whether this is gimmicky or profound, literary or musical, is that Julio’s Day does something other forms of cultural production these days don’t do: it allows for sustained and thoughtful focus, through flashiness and languor, establishing a series of moments — cast over 100 years — during which the reader can appreciate pure, quiet moments of beauty.

¤

Julio’s Day is not flawless. The century, and Julio’s life, progress unevenly. This unevenness is a device used wisely to explore those most compelling moments of a history, often remembered only obliquely. Certain stories draw out over pages, while others are never explicated. Sometimes Julio is only tangential to an event, appearing from the woods clutching a shirt, another half-naked boy in tow. Other times he is not present at all. (Julio’s abduction as a baby drives a search for him in the beginning of the story. Thereafter, what happened to him during that absence fuels the most salacious parts of the tale — sexual intrigue, abuse, and murder.) Occasionally his absence isn’t even the focus of the story. Sometimes he is an absence kept absent — a reversal of the literary trope exploring the presence of the absence. It is only in the title that we find Julio in those moments; it is only because we have been forewarned that this is his day that we know he will return. Julio is not, himself, a compelling enough character to drive reader intrigue. He eschews such attention, in fact, at one point confiding in his brother that he’d requested family members to stop naming babies after him.

Indeed, Julio turns out to be so influential among his family members — a devotion that baffles the reader a bit — that no less than three babes born are named for him, necessitating a key to all the characters in the front of the book, also helpful for tracking individual characters drawn over the span of decades. (It is difficult to convincingly age a character in comics, as Los Bros have attested in interviews about their long-running series Love and Rockets.)

The unevenness of concern is not in the narrative progression, therefore, but in the depth each story is given. Some proclivities are explored in full — nephew Julio Juan’s Rent-era homosexuality, for example, serves to fill narrative gaps for the closeted gay men of Julio’s generation. Yet other significant events are barely acknowledged at all. At times this creates a distressing overlay of disinformation. We don’t, for example, explore the connections between Uncle Juan’s sexual abuse of children, the always feminine nature of his only accusers, or the adult homosexuality of some of his former targets. This leaves for some very troubling causal connections a reader would prefer to be laid bare so as to be discussable, and defendable or refutable. As it is, potential presumptions go unanswered: that the criminal sexual abuse of young boys may be rooted in simple gayness, and not in pathology, or that the only witnesses to the boys’ violations are, well, all the women in the story, a viewpoint for which they are frequently upbraided before proven correct. Yet refusing elaboration allows a key plot point to rest, unchallenged, on basic gender essentialism. And the aspersion that homosexuality may be taught, or passed on, should be put up for discussion, raising as it does the problematic reversal that it could also be untaught, or taken away.

What there is of the story is intriguing, although stretched thin at times. But one must not read Julio’s Day for the events that unfold throughout Julio’s life. Those — even the brightest moments — have nothing on the moments between planned excursions and occurrences, family dramas. Giant, full-page landscapes of trees and hills in shadow, a rising or setting sun. Clouds rolling in to ink over a day, a month, or a year. The impression of snow. A plowed field. The beautiful terrain of a terrible mudslide.

In real life, when you see these things, you say to yourself: Ah! This is what life is about! When Beto draws them, you will say it to yourself again. It is a form of magical realism, but it goes beyond the literary.

¤

A disturbing trend becomes clear on a cursory glance at existing reviews. They note Julio’s ethnicity — “Hispanic” — or that he was “born into a Mexican family” or similar ambiguous phrases that reek of fear of saying something racist. But guess what: titular character Julio is Latino, a man of color, and his family is indeed Mexican, living in the United States, and Julio takes a lover who is white, and other white people pop up in the tale, and they are often racist. (Latino characters exhibit some racist/nationalist moments too.) Also, guess what: there are a couple big old gays in the book.

Indeed, the Hernandez Brothers are Latino — Mexican and Texan parentage — a point I bring up to underscore how unusual it is to be presented with the opportunity to address race in comics at all. It is a perniciously white form of cultural production. According to a 2012 Ladydrawers poll of 120 folks who were interested in working in comics — not even folks who had been published, and therefore felt entitled to the status of “comics creator” — only three percent identified as Hispanic or Latino. Eighty-two percent identified as white, compared to 63 percent of the US population that identified as non-Latino white on the last census.

This lack of diversity gets reflected in the content of comics, too. That same year, Ladydrawers looked at the best- and worst-selling titles from a range of publishers and found that non-human characters rivaled characters of color — or outnumbered them entirely — in every line counted. In DC Vertigo titles, white characters made up 84 percent of all human characters — two percent more, even, than the race identification of the creators themselves, and 21 percent more than the racial breakdown of the greater United States would indicate we all experienced as normal. (In Image Comics from this same time period, less than half the characters of color spoke, and many of those that did only had one line of dialogue.)

Something extremely troubling happens in comics around issues of diversity, whereby whiteness seems so mandated by the medium that it is habitually represented in characters, and further reinforced in narrative content. Even by folks whose lived experience of the world — creators of color, or, for that matter, women, or queers, or folks who don’t identify along a gender binary — would indicate a potential narrative not driven by yet another straight white guy. (I’ve asked hundreds of young people, comics creators, and artists of color to invent a comics character for me — any character of their own design. The character I get back, whether drawn or verbally described, is always white, and usually a dude.)

What the Hernandez Brothers have done to foster and guide the development of independent and alternative and just plain comics for over three decades is astounding. Julio’s Day displays Gilbert Hernandez’s proficiency at establishing a moment of gray intrigue, a fit of jet-black betrayal, white-hot sexual passion, or a jokey panel of awkward-limbed relief. A final silent last page telescopes the whole last century, a life well lived among the well loved.

Yet what’s rarely celebrated is that the work is grounded in a dedication to diversifying both what can be done in comics, and who can be seen to be doing it. I reject the description of “literary” partially because they have their Junot Díazes, their Sandra Cisneroses, their Gabriel García Márquezes, and their Isabelle Allendes already. We have only, right now, Los Bros. How to measure the value of that?

¤

LARB Contributor

Anne Elizabeth Moore is LARB's comics editor, a Fulbright scholar, a UN Press Fellow, the Truthout columnist behind Ladydrawers: Gender and Comics in the US, and the author of several award-winning books. Cambodian Grrrl: Self-Publishing in Phnom Penh (Cantankerous Titles, 2011) received a Lowell Thomas Travel Journalism Award for best book from the Society of American Travel Writers Foundation in 2012. Hey Kidz, Buy This Book (Soft Skull, 2004) made Yes! Magazine‘s list of “Media That Set Us Free” and Reclaim the Media’s 2004 Media and Democracy Summer Reading List. The first Best American Comics made both Entertainment Weekly‘s “Must List” and Publishers Weekly‘s Bestsellers List. Unmarketable: Brandalism, Copyfighting, Mocketing, and the Erosion of Integrity (The New Press, 2007) made Reclaim the Media’s 2007 Media and Democracy Summer Reading list and was named a Best Book of the Year by Mother Jones. Moore herself was recently called a “general phenom” by theChicago Reader and “one of the sharpest thinkers and cultural critics bouncing around the globe today” by Razorcake.

Moore has worked with young women in Cambodia on independent media projects, and with people of all ages and genders on media and gender justice work in the US. Her journalism focuses on the international garment trade. Moore exhibits her work frequently as conceptual art, and has been the subject of two documentary films. She has lectured around the world on independent media, globalization, and women’s labor issues. Co-editor and publisher of the now-defunct Punk Planet, and founding editor of the Best American Comics series from Houghton Mifflin, Moore teaches in the Visual Critical Studies and Art History departments at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

The multi-award-winning author has also written for The Baffler, N+1, Al Jazeera, Good, Snap Judgment, Bitch, the Progressive, The Onion, Feministing, Snap Judgment, The Stranger, In These Times, The Boston Phoenix, and Tin House. She has twice been noted in the Best American Non-Required Reading series. She has appeared on CNN, WNUR, WFMU, WBEZ, Voice of America, GritTV with Laura Flanders, Radio Australia, and NPR’s Worldview, and others. Moore mounted a solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago in 2011 and in 2012 participated in Artisterium, the Republic of Georgia’s annual art invitational. Her work appeared in the 2008 Whitney Biennale, has been exhibited in the Spinnerei in Leipzig Germany in 2010, and made up one of the first conceptual art exhibitions in Phnom Penh, Cambodia in 2010. Her work has been featured in USA Today, Marie Claire, Phnom Penh Post, Portland Mercury, Bust, Entertainment Weekly, Time Out Chicago, Hyphen Magazine, Truthout, Make/Shift, Bookslut, Today’s Chicago Woman, New York Review of Books, Windy City Times, Print Magazine, and the New York Times, among many more. She has lectured at dozens of universities, libraries, and conferences around the globe.

LARB Staff Recommendations

What Kind of Animal Am I?

A comics review in the form of a comic. Graphic graphic novel criticism.

NEW COMICS

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!