Long Live Pope.L, the Friendliest Black Artist in America

Reflections from a former student of Pope.L on his artistic practice.

By Brandon SwardJanuary 12, 2024

TOWARD THE END of his life, the performance artist Pope.L became preoccupied with holes. No, that isn’t quite right. Toward the end of his life, Pope.L returned to holes, which had long interested him. Or, better still: Toward the end of his life, the holes around which Pope.L always orbited rose again to the surface. For Pope.L’s thoughts on the hole, we might turn to his Hole Theory, subtitled Parts: Four & Five (parts one through three were secrets he took to the grave). The text consists of a numerically organized series of points and subpoints, laid out as if it were a mathematical proof. In section 5.1, he writes, “Typically what cannot be seen / Is what we most like to see. / Longing is my favorite / Material for engaging (not picturing / Not illustrating) holes.”

But for an artist like Pope.L, whose principal instrument is the body, whose medium is in that sense always visible, what is this invisible material? The day after the world learned of his death, in that aimless stretch between Christmas and New Year’s, I watched what I believe to be Pope.L’s last artist talk. He was in top form: meandering, grave, irreverent, and purposeful. At one moment, he describes race as a perfume that hovers in and around his work. I think this is what he meant by the cannot-be-seen that is also the most-like-to-see. To catch a whiff of a perfume is to become aware of its presence just as it is slipping away (provided it’s good and not one of those too-shiny bottles that peer from behind the glass at the corner store).

Much of Pope.L’s work is disarming, even silly. The flowers, the fruit, the costumes. But it is also deadly serious, informed by the pressure of a man trying to communicate something his life depended on. With startling self-awareness, he once described himself as a “fisherman of social absurdity.” Indeed, Pope.L’s performances embody the contradictions of our time in the country he called home. Through his practice, Pope.L gave form to the tensions that thrum uneasily at the heart of the “American dream”—those huddled masses yearning to breathe free and the social structures that sort us into separate silos like so much loose grain. It is difficult to watch Pope.L crawl through the gutters of New York City because it literalizes a feeling that far too many of us in this country have, of pulling ourselves through the muck amid the greatest concentration of wealth that human history has ever seen.

As you can by now no doubt guess, dear reader, I’m a bit in my feelings about this one. Just like when David Bowie died and my eyes got hot and itchy as I walked past a chapel playing “Ziggy Stardust” on its carillon. I write these words and want them to do justice to Pope.L and his work, but I don’t know how to neatly fold them up. On the contrary, they seem to wriggle through my fingers, as if Pope.L himself were taunting me from the Great Beyond. But if Pope.L taught us anything, it is how to sit with discomfort, how to inhabit it and make it meaningful, even productive. It is with this goal in mind that I wish to tell you a bit about a man who—in yet another moment of clarity—gave himself the title of “the friendliest Black artist in America.”

¤

I think I only met Pope.L in person once at a gallery opening in the Pilsen district of Chicago. I was asked if I knew him before being introduced and could feel my eyes widen: “Of course!” How could I not? He was dressed as I would often see him dressed, baseball cap angled against graying hair, long-sleeved button-up shirt, at least one missing tooth. He seemed completely relaxed, as if there wasn’t a tense muscle in his body. I remembered all the theater games I played in my youth, which all seemed to circle around a single goal: being ready to respond to anything as honestly as possible.

This was more or less how Pope.L appeared the next time I saw him, mediated by a screen. It was 2020 and everything seemed to be unraveling. Trump was running for president again, the economy was in free fall, and debates over masks raged across the country. Pope.L had finally returned from leave to his teaching post at the University of Chicago, where I was adrift as a disappointing and disappointed PhD student, and he allowed me to take a class in which I desperately wanted to enroll. The course was entitled either “Writing for Performance” or “Writing and Performance”—the conjoining word seemed to change whenever I saw it on the top of a syllabus or in the subject line of an email.

Of course, the coronavirus weighed heavily on performers, those who depended on the proximity that public health experts told us was most dangerous. And so, we got creative. This was also around the time I started studying clown, an eminently physical practice ostensibly allergic to virtuality. We often began class with a simple exercise: look around your space for an object that gives you a feeling and then notice what happens to your body; report your findings, which we would all experiment with and discuss.

One fateful day, my eyes settled upon a microwave cookbook from 1981 that explained the functioning of the then-new appliance to readers through a series of infrared images of a baking potato. I was in Montana, where my father had recently purchased my late great-uncle’s house. He had died unexpectedly, leaving his possessions in place the way parents preserve the rooms of missing children. Since he was also a bit of a hoarder, this physical record stretched far into the past; in this case, to the year 1981.

Through some tangled web of free association that would leave even Freud dizzy, my discovery of this cookbook morphed into a puppet show about the Irish potato famine, starring a marionette horde of fake cockroaches with plastic googly eyes. Like everything else in his class, Pope.L took this performance seriously. He never pushed beyond the internal logic of a piece, even one as patently absurd as mine. I am likely flattering myself, but I’d like to think he didn’t treat us with kid gloves, that the standards he held us to were those he held himself to.

Much of what Pope.L taught me was familiar from an adolescence spent in theater, but it bore repeating. The audience will read into everything. If you’re fidgeting, that’s not a symptom of nerves but information you purposefully chose to communicate. To perform is to be totally and radically present. Your face, your voice, your body, your clothes—each part must work in concert to create an effect. Pope.L would often stress the difficulty of solo performance; how it required a shifting between writer, director, and actor. Good luck if you forgot which hat you were wearing at any given moment.

¤

Unlike some performance artists, Pope.L engaged with and had deep respect for theater, if cheekily so. Take the production of Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun that he directed at Bates College, for which he cast both Black and white actors as members of the same family. A classic of African American theater, A Raisin in the Sun addresses many of the themes of Pope.L’s work: racism, discrimination, money. By staging the play in a way that refused to “make sense,” Pope.L carried out an act of defamiliarization he would return to time and again.

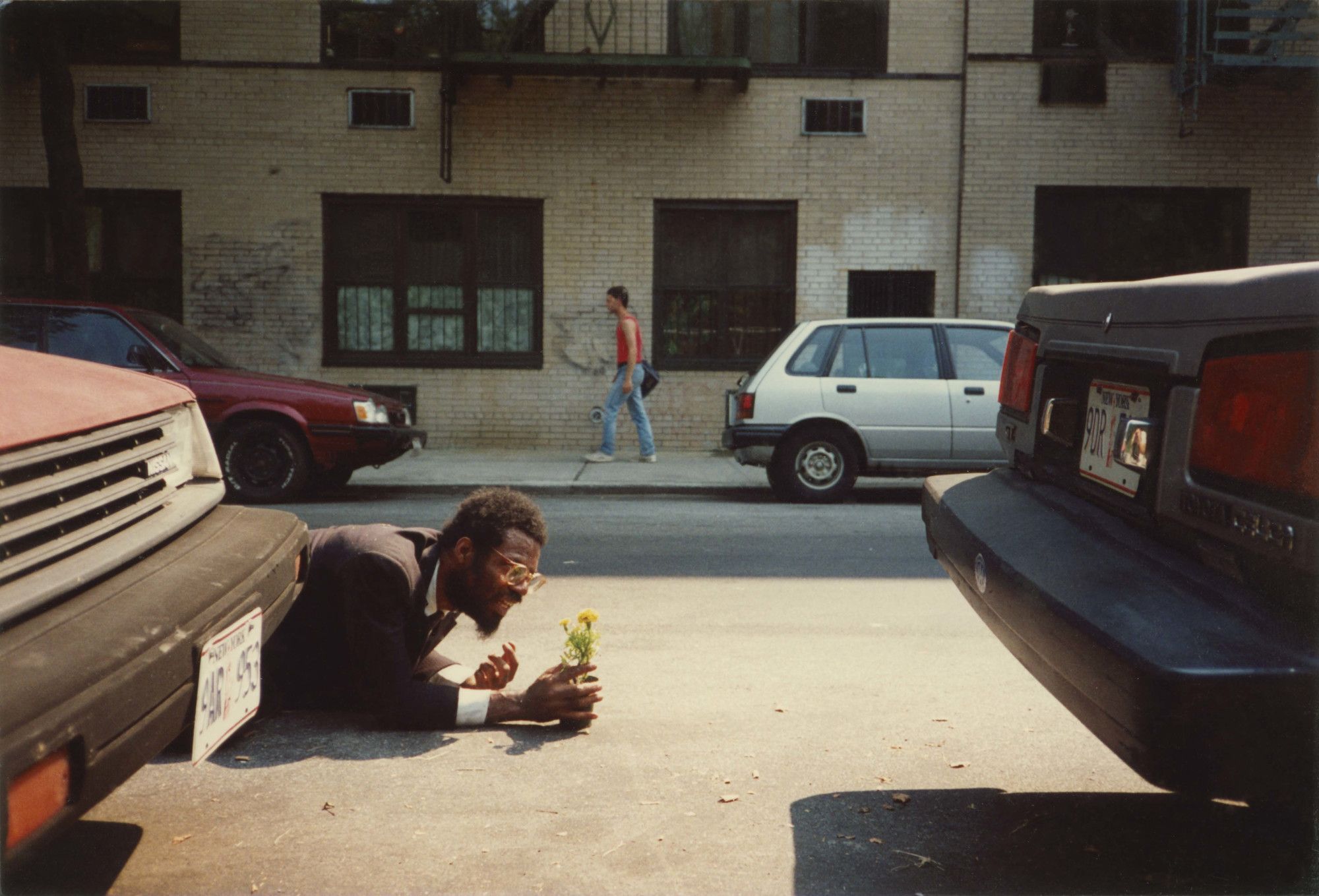

Just after I’d aged out of crawling, Pope.L crawled through the gutter in Tompkins Square Park while wearing a dark pinstripe suit and holding a small potted flower. It is these crawls for which he is best known. The tradition of “endurance art” is a long and storied one, including such luminaries as Chris Burden’s Five Day Locker Piece (1971), Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performance 1980–1981, and Marina Abramović’s The Artist Is Present (2009). In their sheer duration, these pieces strain at the boundary between art and life, or even reject it altogether.

While I was composing a report about platypuses in third grade, Pope.L was attaching himself to a Chase 24-Hour Banking Center in Midtown Manhattan with an eight-foot-long Italian sausage link while wearing Timberlands and a hula skirt made of dollar bills. The piece was his response to a recently passed law that prohibited panhandling within 10 feet of an ATM. This act of “reverse panhandling” reveals the pretensions of then-mayor Rudy Giuliani’s so-called “quality of life” improvements, exposing them for what truly were: a direct attack on the poor.

These endurance artists set my mind on fire. In their immediacy and gravity, they embodied everything I wanted to be. And like any fanboy, I soon got to work. I imagined a series of “invisible performances” that would consist of a fully choregraphed piece I would do in my head with my body held stock-still. For all of 2020, I vowed to never tell a lie. I began to acquire a closetful of mauve clothing to vanish into for a year. I envisioned myself singing the same song on a street corner over and over until my voice had worn down to a hoarse whisper.

But Pope.L was all this and more—just as serious but more playful than anyone else. Over the course of nine years, he slowly crawled the length of Broadway while wearing a Superman costume and a skateboard strapped to his back. The Great White Way, as he titled this piece, references a nickname for one of Broadway’s main sections, which houses the Theater District. Perhaps Pope.L chose the name for that reason. More likely, he had something else in mind altogether, as the heights of American culture have long been dominated by, well, whites. Instead, artists like Pope.L made homes for themselves on the edges, wafting through the air like a trace of perfume.

¤

In the end, the greatest gift I received from Pope.L was that of being taken seriously. I remember talking with him in office hours about an assignment that involved having one end of an orange extension cord wrapped around my neck, with the other tied to a post in the attic. Pope.L commented that it looked as if I’d fastened the cord myself (I had). For him, this was a conscious choice rather than evidence that I didn’t have anyone else to help, except for my dementia-ridden grandmother downstairs who, if Pope.L had had his way, would probably have been enlisted as stage manager.

But my teacher’s true X-ray vision came when he said, “There is a part of you in this character.” I remember this remark like a slap in the face. But with a mix of anger and shame, I realized he was right. Attic Boy was a part of me the way that all my characters—indeed, all my work—are parts of me. They came from me, and we are linked. They might have come from somewhere else, but they did not. My entire life has led up to this moment when I am having a deadly serious conversation about my secret desire to become the attic dweller, finger-painting and talking about art, clad in only underwear and a tank top.

One of my favorite artists, Bruce Nauman, once made a neon sign that read “The true artist helps the world by revealing mystic truths.” I think this is correct. The artist is that rarest of creatures: the universal within the particular. Just as I was tethered to my characters, so too was there a bit of Pope.L in the money skirt and the crawling Superman. But these performances also reached far beyond the confines of his idiosyncrasy. They are records of race, of class, of gender—all the fault lines of the body politic to which we belong.

Pope.L’s work is often painful to watch. The way he gives form to our cultural contradictions is direct and unsparing. He was, after all, the man who spent hour upon hour reading, chewing, and regurgitating a copy of The Wall Street Journal while clad only in flour and a jockstrap (the Journal responded with a mix of confusion and condescension). This is to say nothing of the 14-foot-long cardboard “schlong” protruding from his crotch and propped up by a wheeled office chair (a piece that caused him to lose his NEA funding).

This sort of challenging work clearly isn’t for the fainthearted; art was for Pope.L a matter of life and death. In his 1978 piece Thunderbird Immolation, the artist doused himself with the sort of cheap fortified wine marketed to the (always already Black) down-and-outs of the inner cities and arranged a circle of matches around himself. Viewing Pope.L seated cross-legged on a meditation mat, it’s hard not to think of the self-immolation of Mahāyāna monk Thích Quảng Đức 15 years earlier in protest of the South Vietnam government’s persecution of Buddhists under President Ngô Đình Diệm, with support from the United States.

And so, I was curious to see member: Pope.L, 1978–2001, an exhibition at MoMA of 13 of his performances that set itself the impossible task of making a show about an artist whose medium was himself. In true Pope.L fashion, however, the artist wasn’t wholly absent. For me, the best piece was a hook near the exit on which a backpack might be hung. An empty hook meant that Pope.L was somewhere in the museum, carrying said backpack. When I went to the show, the backpack hung on its hook, where it will remain whenever the piece is displayed, from now into the dim-bright future.

¤

Featured image: Pope.L. How Much Is That Nigger in the Window a.k.a. Tompkins Square Crawl, 1991. Five inkjet prints; Timberland leather boots; asphalt. Acquired in part through the generosity of Jill and Peter Kraus, Anne and Joel S. Ehrenkranz, the Contemporary Arts Council of the Museum of Modern Art, the Jill and Peter Kraus Media and Performance Acquisition Fund, and Jill and Peter Kraus in honor of Michael Lynne. © 2024 Pope.L. Courtesy of the artist.

LARB Contributor

Brandon Sward is an artist, writer, and organizer in Los Angeles. He used to edit the LARB Short Takes section, and is currently at work on a book about growing up queer and biracial in Colorado Springs, the “Evangelical Vatican.”

LARB Staff Recommendations

Writing Blue

Terry Nguyen explores blue essays for LARB Quarterly, no. 40: “Water.”

Palestine Is a Story Away: A Tribute to Refaat Alareer

A tribute to Palestinian writer and activist Refaat Alareer by poet and scholar Mosab Abu Toha.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!