Life in Stasis: Behrouz Boochani’s Manus Prison Literature

A harrowing book about refugees in Australian detention reveals much about the national character.

By Eleanor DaveyMay 18, 2019

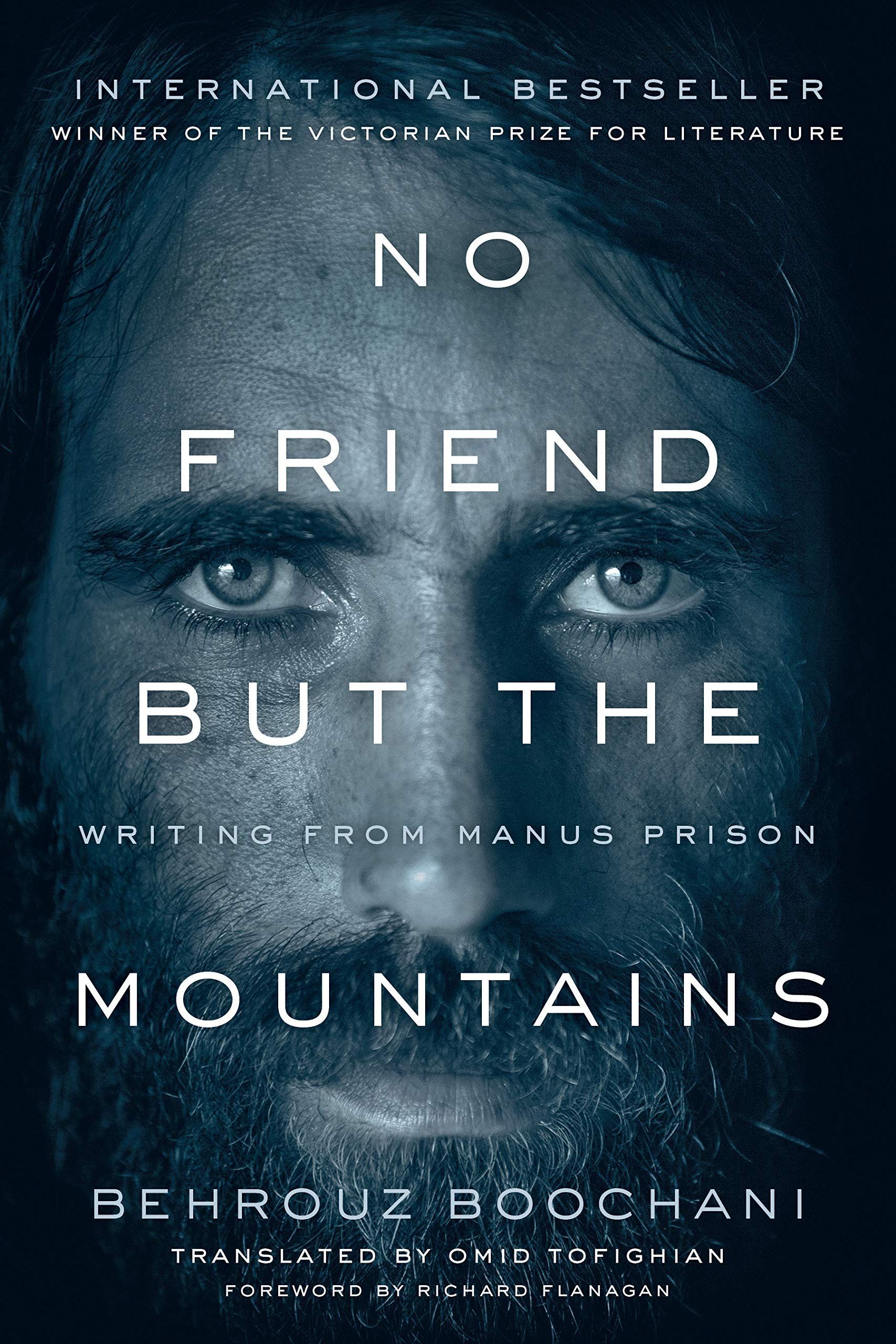

No Friend but the Mountains by Behrouz Boochani. Anansi International. 416 pages.

A MANGO TREE grew in the yard of the prison where Kurdish journalist Behrouz Boochani lived from 2013 to 2017. In the early days, prisoners who managed to scavenge a fallen mango would divide and share it. But as isolation and hunger increased, the only person who would still share what he found, “a gesture of courtesy in the manner of a child,” was a young Kurdish man known as The Gentle Giant. His generosity — as documented by Boochani — becomes a rebuke, an unsettling reminder of better worlds, to those who had let kindness wither.

The book No Friend but the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison is an extraordinary insight into the life of several hundred men held in offshore prisons under the Australian policy of immigration detention. The issue of refugees arriving by boat has been a rare point of bipartisan consensus in Australia: right-wing Prime Minister John Howard declared in 2001 that “we will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come,” but no government since, whether on the left or right, has meaningfully departed from the position that no one trying to reach Australia by boat would ever settle there. Offshore processing gave way to indefinite detention, described by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture as having “violated the right of the asylum seekers, including children, to be free from torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.” Since July 2013, over 3,000 people have been sent to Papua New Guinea and Nauru for offshore processing; more than 1,000 people were on both islands in February 2019, Boochani among them.

His writing was smuggled out via text message over a period of several years, collated by his interpreter Moones Mansoubi, and translated into English by Omid Tofighian. The result is a lyrical but also suffocating evocation of aimless days under the baking sun, dehumanizing queues, essential and often absurd acts of resistance, banal abuse, and extreme violence.

The prison in Boochani’s account is a stinking, wretched place; a decaying cattle yard, belching with the physicality and trauma of the men trapped inside. But it is also impersonal, impassive, an artificial world of chain-link fences and pre-fab buildings, ceiling fans that rotate ineffectually, and sewers that empty too close to where people have to live, feeding jungle plants whose vivacity contrasts sharply with the immobility of the imprisoned men.

There are a number of character studies, of individual prisoners mostly known not by their names but by personas or features brought into relief by the duress of flight and incarceration: The Hero, The Rohingya Boy, The Father of the Months-Old Child. Australian officers sit stolidly and threateningly on the white plastic chairs that scatter the grounds.

Boochani is an acute observer of human behavior, but it is not the human that matters in this system. Prisoners are assigned a number and addressed exclusively by that number. When queuing for medication, lining up for meals, asking to use a telephone, prisoners must use their number and not a name. The queue itself is an instrument of control in Manus prison, a bureaucratic technique of torture that acts upon the very men who constitute it. Boochani refers to the prison logic as the “Kyriarchal System,” a concept that reflects the multiple and interacting structures of power and repression through which the prison functions.

The complicity of medical professionals has been one of the recurring features of this system. In the prisons at the time of Boochani’s writing, medical services were provided by a pseudo-non-governmental organization called International Health and Medical Services (IHMS). “When a prisoner falls ill,” Boochani writes, “it is as if his legs have been sucked into a maelstrom, drawing him down deep within it.” One of few named prisoners is a victim of the medical system — Hamid Khazaei, also known in the book as The Smiling Youth, who died in September 2014 after contracting a leg infection. A coroner’s report found that inadequate care, including a lack of antibiotics, caused Khazaei’s entirely preventable death. Boochani himself is so afraid of the IHMS clinic that he chooses to have a tooth cavity cauterized with a hot wire by a few of the Papuan guards.

Boochani traveled via Indonesia, enduring a perilous boat journey in search of asylum that ended in arrest by the Australian Navy and detention first on Christmas Island and then, from August 2013, on Manus Island. The tense wait for departure from Indonesia and harrowing attempt to navigate a hostile ocean in a leaky boat make up the first three chapters of No Friend but the Mountains. Much of the book is timeless, flashing forward or backward, capturing scenes that take place in memory and imagination as well as scenarios that have occurred so many times they could be any time. Its final chapters relive protests and clashes in February 2014, in which dozens of people were injured and Iranian Kurdish asylum seeker Reza Barati was beaten to death. “Men all over the place with crushed bodies / Men all over the place with smashed bones.” The 23-year-old Barati was The Gentle Giant in Boochani’s stories.

No Friend but the Mountains allows us to rethink the violence of these offshore sites as integral, not alien, to Australian society. Australians are taught, or were at least when I went to school, that we live on the “only island continent.” The bulk of the population cleaves more or less to the coast; picturesque beaches dominate tourism campaigns, postcard-friendly imagery of where “our” country meets the ocean that separates us from everyone else. White sand and blue skies are part of the whitewashing of history: the notion that modern Australia’s founders were invaders and aggressors as much as they were discoverers, settlers, and pioneers — indeed, that genocidal violence made settlement possible — appears in public debate but is not yet acceptable in the nation’s story about itself.

The persistence of enclosed spaces of repression, from the convict gulags on Norfolk Island and Tasmania, to colonial “protectorates” of indigenous people, to the refugee compounds on Manus and Nauru, is presented as a series of aberrant blots on the record instead of a constitutive reality.

While its author remains officially unwelcome and unwanted, No Friend but the Mountains won two prestigious prizes at the 2019 Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards. But it deserves, and will have, a much wider readership. As a detailed reading of colonial power, Boochani’s book charts a global landscape of fortified borders, spaces of removal, and policies of dehumanization.

In April 2016, the Papua New Guinean Supreme Court ruled the detention center on Manus Island was “illegal and unconstitutional.” In June 2017, the Australian government and its subcontractors agreed to pay more than AUD $70 million following an out of court settlement with refugees and asylum seekers, compensation for illegal detention in unsafe conditions. In November 2017, the center closed, but the several hundred men living there, including Behrouz Boochani, remain trapped on the island in “alternative accommodation.”

Boochani describes the day the Australian Minister of Immigration visited Manus prison with only one message: “You have no chance at all, either you go back to your countries or you will remain on Manus Island forever.” Perhaps he was right.

¤

LARB Contributor

Eleanor Davey writes about the histories of aid, activism, and anti-colonialism. She is the author of Idealism beyond Borders: The French Revolutionary Left and the Rise of Humanitarianism, 1954-1988 (2015), which was jointly awarded the International Studies Association Ethics Section Book Prize (2017).

LARB Staff Recommendations

What Makes an Immigrant Good?

Simon Lee reviews "The Good Immigrant: 26 Writers Reflect on America," which offers a range of perspectives on assimilation, pluralism, and Othering.

“Good” Refugees, “Bad” Refugees: A Conversation in Paris with Viet Thanh Nguyen

A discussion of a new collection of essays by immigrant writers.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!