Life and Death in Rio de Janeiro

With the Olympics just on the horizon, Jez Smadja reviews "Rio de Janeiro: Extreme City".

By Jez SmadjaJuly 31, 2016

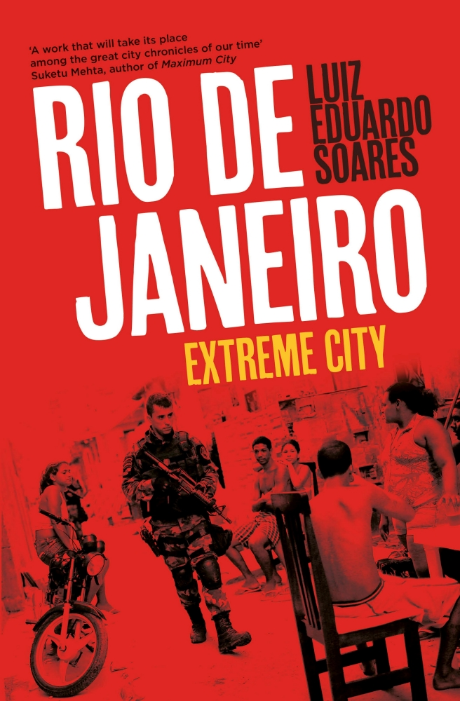

Rio de Janeiro: Extreme City by Luiz Eduardo Soares. Penguin. 320 pages.

IN THE BOOKSHOPS with weeks to go before the 2016 Summer Olympics, Luiz Eduardo Soares’s Rio de Janeiro: Extreme City is possibly not the book that the International Olympic Committee, the Visit Rio tourist board, the mayor Eduardo Paes, or indeed many cariocas — a breed of people particularly sensitive to any slurs against their city — will want you to read. There’s barely a mention of the breathtaking scenery, the historic samba schools, the state-of-the-art museums it has delivered in time for the Games, or the new metro extension and light rail system it hasn’t, or not yet at any rate.

In a month when the state of Rio declared a state of financial emergency, a month also when the policemen who fired 63 bullets into a white Hyundai — killing five innocent black men inside — were all given bail, Soares’s city confidential is a timely corrective to the postcard view of Brazil’s former capital: a seductive image it seeks to sustain at considerable cost. Many chapters of Rio de Janeiro: Extreme City read like a James Ellroy thriller, flush with a cast of crooked congressmen, trigger-happy policemen, druglords, evangelical pastors, ambulance chasers, and an economist turned international trafficker. The principal difference being that everything you read here is more or less true.

Previous attempts to distill the rare essence of this cidade maravilhosa (the wonderful city), be it João do Rio’s belle époque dispatches in The Enchanting Soul of the Streets or Ruy Castro’s Rio de Janeiro: Carnival Under Fire, have resulted in works of stark chiaroscuro, pitting the baroque against the modern, the rich against the penniless, the sublime against the beautiful. The Enchanting Soul, written when Rio was better known for its coffee, its gaslamp-lit boulevards, and periodic bouts of yellow fever, captures a period known as “regeneration,” when the then capital was remodeling itself as the Paris of Latin America. Ruy Castro’s slim volume, published a century later, resorts to the more familiar trinity of music, football, and carnival, with an undertow of violence beneath the surface.

Soares’s contribution to this genre is altogether less smitten with its subject, but no less absorbing for it. This avuncular public figure — an academic and activist who served as National Secretary for Security under President Lula in 2003 — has been one of the most far-sighted critics of the county’s war on drugs. That war has legitimated a silent genocide against young black men, and seen Brazil build the fourth-largest prison population in the world. Soares has also untiringly locked horns with the police, an often corrupt and inefficient institution that every year kills, in Rio alone, more civilians than all the police forces in the United States combined. It was largely due to Soares’s untiring efforts to root out corruption that he was dismissed from Lula’s government as well as a similar role in the state of Rio de Janeiro, events he goes some way to elucidating in this new book.

Those attributes that made Soares a failed politician — principles, probity, and intransigence — are precisely what make him such a revered intellectual and critic, one that doesn’t lack the popular touch. In collaboration with ex-police officers André Batista and Rodrigo Pimentel, he wrote the two books that director José Padilha made into the blockbuster Elite Squad franchise. The first film lifted the lid on BOPE, Rio’s special ops police outfit that operates under a state of exception on the fringes of the city. The sequel, The Enemy Within, Brazil’s top-grossing domestic film of all time, went one step further, exposing the web of business and political interests profiting from the power vacuum in Rio’s favelas and suburbs.

Rio de Janeiro differs from Soares’s previous books in that he now turns the camera on himself, providing a first-person account of his experiences growing up in Rio, and his encounters with the city in both a personal and professional capacity. The story begins in earnest in Rio’s leafy Laranjeiras neighborhood where the young Soares dreamed of seeing his beloved Fluminense team play at the Maracanã stadium. On the night of March 31, 1964, he had a front row seat for a different kind of contest when, outside his bedroom window, army tanks trained their guns on the adjacent Guanabara Palace. This was the night when the military generals, fearing that Brazil would fall the way of Cuba, staged a coup against President João Goulart. The dictatorship that followed provided a watershed moment in the modern history of Brazil, and for Soares it coincided with his coming of age both emotionally and politically.

Soares chose pacific resistance to fight the junta, but many others took up arms, like Dilma Rousseff, the country’s now-impeached president. Soares tells the story of Dulce Pandolfi, today one of the country’s leading historians, who at the age of 21 was arrested by DOI-CODI (Departamento de Operações de Informações–Centro de Operações de Defesa Interna, or Department of Information Operations–Center for Internal Defense Operations), the repression’s infamous information service, and like Rousseff was brutally tortured. The scenes in the basement of the army police barracks in Tijuca, a neighborhood in Rio’s Zona Norte, make chilling reading. Even if Brazil’s junta was not nearly as bloodthirsty as its equivalents in Argentina or Chile, its torture techniques were unrivalled, its interrogators having received special training from France and the United States.

Some three decades later, Soares, now Rio’s undersecretary for security, needed to react to a fatal incursion by the police into a densely populated comunidade in the Zona Norte. For the author, the continuities between the dictatorship and the democratic era are nowhere more apparent than in the police force. Between 2005 and 2014, police operations in Rio resulted in 5,132 deaths, the vast majority filed as responses to “acts of resistance” and shelved without further investigation. Over the past few years, Soares has been one of the architects and key voices behind a constitutional reform bill (PEC-51) to demilitarize the police force and reduce police lethality.

But the author doesn’t wear his policy hat in Rio de Janeiro: Extreme City, offering instead a more plot-driven tale about the imbrication of the police and the criminal underworld, one that was forged during the dictatorship. Each chapter gently tugs at this thread, revealing how former DOI-CODI torturers created militias in the city’s western exurbs to provide security for local mafiosi. When, incredibly, in the early 2000s militiamen managed to get elected to local government, they then controlled lucrative public contracts that they could carve up between them, just as the numbers game cartel had done with the Rio Carnival in the mid-1980s.

But the rot goes deeper still, affecting an entire political edifice based on cronyism, bargaining, and plundering the public purse. To Soares’s immense disappointment, this was particularly rife in the Workers Party (PT) under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, a party that arrived full of promise in 2003, with a commitment to rooting out corruption, setting it at arm’s length from the old politics of “rouba, mas faz” (“he steals but gets the job done”).

Inside Lula’s government, Soares saw the first inklings of the kinds of arrangements that would land the party in its current moral quagmire. He reserves his sharpest barbs for the PT’s chief of staff, José Dirceu, who was jailed in the mensalão scandal, a cash-for-votes scheme that almost sunk the party in 2005, but proved to be only loose change compared to the multibillion dollar Petrobras scandal, also orchestrated by Dirceu, which has tarnished Brazil’s entire political class and paralyzed the national economy.

In an interview with Folha de S.Paulo, Soares revealed that two chapters from Rio de Janeiro: Extreme City were part of a new script for director José Padilha about the mensalão scandal entitled Never Before in the History of this Country. The national development bank BNDES, which had agreed to finance the film, mysteriously pulled the plug. In Soares’s opinion, it was José Dirceu who torpedoed the project, worried about the effect it would have on his court case.

If the author sees any glimmer of light in this nest of vipers, it is in the 2013 protests when citizens across the country took to the streets to denounce the spiraling cost of the World Cup and the parlous state of education and health in a country with one of the highest tax rates in the world. Every Brazilian knows the price of corruption. As Deltan Dallagnol, the lead prosecutor in the Petrobras investigation, recently said, corruption is “a serial killer disguised as holes in the road, shortages of medicine, street crimes and poverty.”

In the million-strong crowd on Rio’s Avenida Presidente Vargas, a 16-lane road built by the country’s first dictator in the 1930s to parade his troops along, Soares sees cariocas of all ages and colors. Amid the many messages on placards and banners that day, perhaps the unifying theme was the pressing need for government accountability and representativeness. The aporia between the state and the people underwrites everything from extrajudicial assassination by the police to runaway political graft, and overcoming it is the sine qua non of a functioning democracy, a democracy that can finally bury the ghosts of dictatorship.

¤

LARB Contributor

Jez Smadja is a journalist and translator who has contributed to the Guardian, Press Association, Time Out, and Vice. He also edited and published the quarterly music journal Shook Magazine. He is currently writing a book about cannibals, Christianity, cocaine, and coffee in Brazil.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Global Parties, Galactic Hangovers: Brazil’s Mega Event Dystopia

Whether it’s the World Cup or the Olympics, in London, Tokyo, or Rio de Janeiro, mega events are about real estate.

World Cup Diary: Losing Brazil 2014 to the Future

Losing Brazil 2014 to the Future

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!