Letter from Australia

What American publication means to Australian writers

By Sam Twyford MooreJune 25, 2012

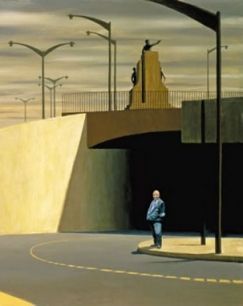

Cahill Expressway, Jeffrey Smart (as seen on cover of Peter Carey's The Fat Man in History)

HIGH ON ONE OF THE WALLS of Shearer’s Bookstore, an independent bookstore in the Sydney suburb Leichhardt, there is a banner suspended artfully, which reads “The ONLY Australian Bookshop to have launched A PULITZER PRIZE WINNER.” The capitals are theirs and the book in question is Geraldine Brooks’s March, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 2006. The book was launched on April 11, 2005 according to the floating sign. I spent a good ten minutes looking up at the sign — between browsing books — trying to figure out when it would have been raised and installed. It was, obviously, printed after Brooks won the prize, but Pulitzer Prizes are awarded in late May, meaning that the store printed the banner more than a year after the launch. It seems like a strange thing to celebrate, but it only proves the importance of American recognition to the Australian book industry and its writers.

This is not a review of The Best American Short Stories 2011 — or at least it is not a review of any of the stories that have made it into its pages. Don’t let the byline mislead you. How do you review something that has already been deemed the Best without wasting significant essaying time denouncing the whole idea of anthologizing? I can only think of bad puns anyway: “middling at Best.” I’m not interested in writing a beat down on American short fiction, a la Elif Batuman's holier-than-thou write up of the 2004 and 2005 Best American Short Stories collections in n+1.

Instead there is an opportunity here to isolate Geraldine Brooks’s introduction, indeed her role as editor, and to meander elsewhere (definitively elsewhere). The route for this elsewhere doesn’t involve a beat down of Brooks as editor either. Her credentials are solid, at least when it comes to American-ness. The only possible slight against Brooks might be that she admits in her opening words to not being a short story writer.

But here is a hell of a question: What of her Australianness?

It is not necessary for the editor of the Best American series to be American — Margaret Atwood and Salman Rushdie had edited earlier versions of the anthology — but there must be some connection with the country to take such a position. Brooks became an American citizen in 2002, while retaining her Australian passport, and had spent years as a foreign correspondent before that. Her father was American — a Californian musician who travelled to Australia to play in a dance hall band, and was stranded in the country after they ran out of money. This duality is evident on her austere website where she breaks her public appearances down into ‘Events USA’ and ‘Events Australia’. Brooks felt the urge to write an essay explaining why she had never written a novel set in Australia (the easy line to make here is that this article was published in the The Washington Post rather than an equivalent Australian publication) and the necessity to take up a defensive position is common for expatriate writers.

Brooks is defined as otherworldly by Series Editor Heidi Pitlor who, after having passed on the 120 stories she had whittled down for Brooks to choose from, writes in her introduction to Brooks’s introduction (a Babushka doll of a book), with what she describes as a slight grimace, "Welcome to American short fiction. Please don't judge us." Apart from the obvious fact that that was precisely what Brooks was there to do — to judge American short fiction, to pick the Best — Pitlor’s feeble request for mercy also seems to further frame Brooks as the outsider looking in.

Brooks does not shy away from the role of international umpire, giving a dressing down to American writers in her introduction, including a list of her "carps of the day," dropping the politeness normally associated with a tasteful historical novelist, and diving into sublime poetics like "Enuf adultery eds. Too many stories about the wrong cock in the wrong cunt/anus/armpit/Airedale." The shortest of her corrective suggestions runs: "Foreign countries exist."

In the same year as being asked to edit Best American Stories, Brooks was invited to deliver The 2011 Boyer Lectures, a series of radio lectures aired by the ABC (Australian Broadcasting Commission) on “major social, cultural, scientific or political issues.” Brooks titled her lectures The Idea of Home, establishing the theme of ambiguity of belonging — both as a dual citizen of Australia and America, but, in a more abstract sense, a novelist with a background in journalism. Previous speakers had also included expatriate Australian writers returning home, including New York-based novelist Shirley Hazzard (Coming of Age in Australia) and Oxford academic Peter Conrad (Tales of Two Hemispheres). In 2008 our prodigal son Rupert Murdoch delivered a series of lectures under the title The Golden Age of Freedom. Brooks used her lectures to comment on Australia’s climate change and immigration policy, aware of the tensions of being an expatriate writer come home to pass judgment. Her success in America means she has a keen audience waiting for her at home, but Brooks is also aware of our insecurities when it comes to our own fiction.

If you walk into a bookstore in Australia, you will most likely find that the local fiction segregated from the mass of other “world literature” titles. Australian Literature typically sits on the shelf by itself, isolated in the Pacific region of the room. Brooks remains in these shelves, despite her new citizenship and the Americanness of the subjects of her novels. Peter Carey, probably the most famous of our American-based novelists, at least has the politeness to set part of his post-U.S. novels in America. When asked during an interview with The Paris Review if he felt pressure to return to Australia, he was quick to qualify that... "I only write for Australians."

This tension has played out in curious way in Carey’s fiction. "The Americans would come, he said. They would visit our town in buses and in cars and on the train. They would take photographs and bring wallets bulging with dollars. American dollars." So prophesizes one of the characters in Peter Carey's famous — famous, at least here in Australia — short story American Dreams. The townspeople of the Melbourne suburb Box Hill live in anticipation of the arrival of these fabled Americans and when they do finally eventuate with their cameras and American dollars, the townsfolk are overwhelmed. In 2010 when the Australian dollar past parity with its U.S. counterpart, it seemed unlikely that the Americans would come with their American dollars in such high numbers again and the story seemed suddenly dated. But it seemed even less likely that an American would write a short story about the Australians descending on Palo Alto with our newly inflated currency; we just don't capture your imagination the way you capture ours.

Like do you guys get how hard we are trying to impress you? I am sorry to break out of essay-voice and address this so directly, but I need you to understand how much this means and how it can be thrown back in our faces. I was aware, for instance, of the way that Australians look to Americans for cultural confirmation from a very early age. I remember watching the 69th Academy Awards when I was twelve. Something curious happened when Geoffrey Rush was announced as the winner of the Best Actor Oscar for his hypomanic, fast-talking performance in Shine: the telecasters included a small box in the bottom right hand corner of the screen, a cutaway to a lounge room filled with women sitting on a set of couches. The accompanying explanatory text read GEOFFREY RUSH’S MOTHER MERLE.

Merle, on hearing that her son had won the major award, promptly broke into a standing cheer, before falling over backwards. It was a moment of national pride perhaps, but one that provided plenty for us to perform what A.A. Philips termed our "cultural cringe." You can understand Merle's overjoyed lift at her son's win, but her inclusion in the telecast is curious. Did they have other mother's lined up to cut to if the award had gone another way? It is hard to imagine fellow nominee Ralph Fiennes’s mother performing the same geriatric gymnastics for the viewers at home. Was Merle, and Australia's national character, taken advantage of or was it something Merle/we signed up to willingly?

Those acting prizes come with high expectations and we are heavily invested in them. But we are remarkably less receptive and enthused when it comes to our literary producers doing well in America. If you went by the tone and character of the press and literary chatter you might just assume that we suffered some psychic trauma when Peter Carey's moved to New York permanently in the early 1990s. Carey was our literary star having won the Booker Prize for Oscar and Lucinda, the seeds planted in early short stories like American Dreams. (Although it is often countered that in losing Peter Carey to the pull of the US, we can at least console ourselves in having gained Nobel Prize winning author J.M. Coetzee who moved to Adelaide from South Africa and became an Australian citizen in 2006.) The press around his divorce focused on the fact that he would not agree to return to Australia to live in Brisbane where his wife was set to take a job, effectively declining to support his wife's career. Carey remained in New York where he now teaches at Huntington College.

On the release of his novel Theft: A Love Story the journalist Susanne Wyndham wrote a series of articles for the Sydney Morning Herald, focusing on Carey’s divorce and the part that it played in the book, and by association a long line of questioning with regards to his move to America. In The Paris Review interview, Carey offered, “When one leaves, the unsaid accusation is that you’re going somewhere else because Australia is not good enough for you.” Wyndham did not leave it unsaid in her profile…

Over the years, Carey has given a variety of reasons for his move to New York. At first it was to take up a short-term job as a writing teacher vacated by Tom Keneally. It was for fun, a "moral holiday" from the responsibility of being a writer in his native country. Sometimes he has said it was to allow his wife, Alison Summers, to pursue her theatre directing ambition. He told a journalist last year it was because Summers "hated" Australia, an accusation she hotly denies.

Wyndham went on to publish speculation about Carey’s book deals, suggesting that in his move from the local University of Queensland Press to Random House Australia was worth $2 million for a three book deal and that his U.S. advance totalled in $350,000 for My Life as A Fake. Wyndham pursued an interview with Carey’s ex-wife Alison Summers, too, almost as if The New York Times had published with Susan Bellow after the publication of Saul Bellow’s Herzog. This of course amounts not to literary journalism, but little more than tabloid gossip, which only serves to underscore our anxiety about Carey’s success and existence in America. So what if Allison Summers wanted Carey to move to America? Geraldine Brooks, Shirley Hazzard and Christina Stead all married American men. The more interesting question — although I’m guiltily not approaching it here — is what America did to their writing after the fact.

The gravitation towards America as a place to learn craft is partly historical, and we may simply be following a cultural lead — the number of publications in America, as well as readership, is certainly attractive, but it seems to be more a case of young Australian writers going to study there in order to, effectively, legitimize their practice. An artist friend of mine said that he was getting calls from galleries and curators only once his plane took off from Sydney en route to Berlin — that he had somehow showed some extra commitment by relocating, even though his work had not necessarily changed in shape nor form. There might be a view by Australian writers that they need to start out in America and then to work outwards, or to work their way back home. Carey and Brooks may be serving as role models for these aspiring authors, where their geography is perceived to be as central to their success as the writing itself.

In her polemic The World Republic of Letters (Convergence), Pascal Casanova remaps the world’s literary centers. Casanova is overwhelmingly gallocentric — as the friend who recommended the book to me said, "take it with a pinch of garlic salt" — arguing that writers such as Borges and Cortazar were discovered by being translated in French, rather than English, putting Paris at the centre of her new world order. Casanova — much like the committee behind the Nobel Prize in Literature — is openly attempting to decentre America in the literary world. But countries such as Australia are not in the same place to make such a radical move.

It becomes necessary for writers to travel to these other centres to pursue greater opportunities. Chloe Hooper moved to New York from Melbourne to work on her first novel and to study under Philip Roth at Columbia University. The resulting novel from this time, The Children's Book of True Crime, was picked up by super-agent Andrew Wylie, and, subsequently, was subject to an intense bidding war between interested publishers. The Australian media jumped on the story, growing a sudden avid interest in the mechanics of the book industry. Wylie did his part to fuel the story by contriving a certain level of spectacle, locking himself in a Sydney hotel room in order to do business for the book. Hooper shied away from suggestions of a bidding war, and it put a lot of downward pressure on a debut novel. Wylie brought the glitz and the glamour to Sydney and you could practically hear people crying out, "This is how they do it in New York!"

Hooper’s book came and went, and seems less of a success than her follow up The Tall Man, a non-fiction account of a particularly horrific death in custody of an indigenous man on Palm Island. Still, it cemented her reputation and it allowed the Australian media to speculate on her “six-figure sum,” continuing our fascination with the financials. It seems unlikely though that few Australian writers would aspire to Hooper's level of success. The idea never seems to me to be to consciously find and attract an audience in America — but to do work over there that which impresses people here.

Most publishers agree that Nam Le was a once in a lifetime breakthrough. The press around his debut collection of short stories The Boat was that he "came from nowhere." But nowhere was a big, obvious, and very conspicuous place in his case.

Le was a young Melbourne based lawyer who moved to America to enroll in the two-year MFA program at The Iowa's Writers' Workshop. Le’s success did more to promote Iowa’s program than the Melbourne University undergraduate degree. It was there that Le had written an honors thesis on W.H. Auden in rhyming tetrameters and heroic couplets. Le could have enrolled in any number of postgraduate creative writing courses in Melbourne, or elsewhere in Australia. The rise in these creative writing degrees in Australia, in fact, is partly attributable to the Iowa institution, along with the University of East Anglia in the UK. It is this education program that gives Iowa its classification as one of the five UNESCO Cities of Literature; one that it now shares with Melbourne, along with Dublin, Edinburgh, and Reykjavik.

The opening short story of Le's collection The Boat, "Love and Honor and Pity and Pride and Compassion and Sacrifice," is in fact set in Iowa Writers' Workshop, and might suggest the attachment that Le has to the place and how closely he associates it to his identity as a writer.

"If you ask me why I came to Iowa, I would say that I was a lawyer and I was no lawyer. Every twenty-four hours I woke up at the smoggiest time of morning and commuted — bus, tram, elevator, without saying a single world, wearing my clothes that chafed and holding a flat white in a white cup — to my windowless office in the tallest, most glass-covered building in Melbourne ...

Melbourne didn’t take notice of Le until this sentence was published in America. Le was already signed to Knopf before signing to Penguin Australia. It is hard to imagine that the Australian publisher would have gone for a collection of short fiction — which are not seen as having much appeal to the local market — without the commitment of the U.S. publisher. In Australia writers compete for very limited space, extremely limited resources and minute audiences. The Boat sold around 6,000 copies in Australia in its first year and that put it in the bestseller category. Other writers have followed in Le’s footsteps, enrolling at Iowa and chasing U.S. publication.

These often feel like miraculous conceptions — while other writers publish widely at home, a single short story in an American magazine seems to have the value of ten or more here at home. Cate Kennedy's profile rose after she had a short story published in The New Yorker — which her publisher actively pushed for — she has gone on to publish two short story collections and a novel, as well as editing The Best Australian Stories 2011. The little heat you generate in the U.S. burns hotter back at home.

There is then, something of a self-interested side to writing this essay with an American publication like the Los Angeles Review of Books in mind as its home. It is as strategic as any of the moves played by any of the writers above, if not more so because I have just laid them out. I want to be taken seriously at home, and I truly feel that I need to come here to make it happen there.

Recommended Reads:

LARB Contributor

Sam Twyford-Moore is a writer of fiction and non-fiction. His debut collection is due in 2012 through Xoum. He also hosts The Rereaders podcast (www.therereaders.com).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Letter From Guatemala

"Why?" is a question that hounds anyone trying to make sense of the violence against women in Guatemala.

Letter From Detroit

For every abandoned business, store, school, or church in the city, a new one has been built in the suburbs.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!