Juan Felipe Herrera’s “Akrílica” and the Not Yet of Latinidad

Renee Hudson considers “Akrílica,” a collection of poems by Juan Felipe Herrera.

By Renee HudsonSeptember 8, 2022

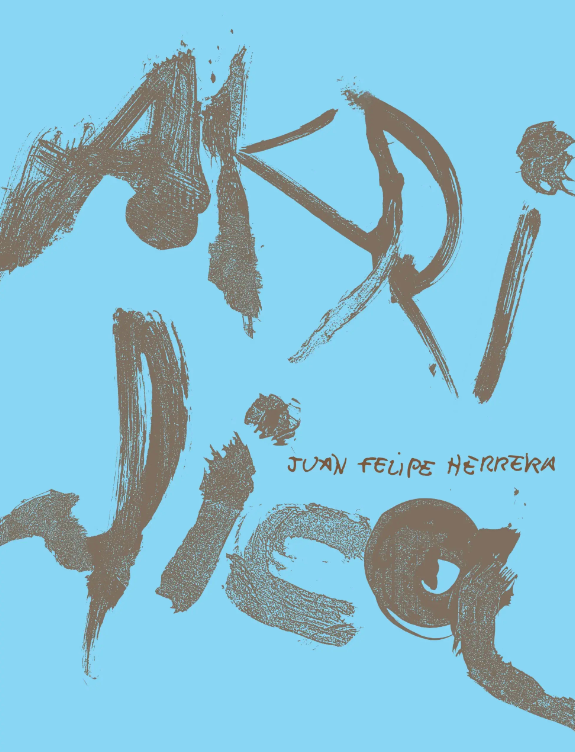

Akrílica by Juan Felipe Herrera. Noemi. 168 pages.

IN HIS INTRODUCTION to Juan Felipe Herrera’s poetry collection, Akrílica (2022), Farid Matuk describes the collection, first published in 1989, as an act of “retrieval” rather than “recovery.” “We steal Akrílica away from literary institutions, away from the discipline of literature, and away from traditions of experimental poetics that should hope to claim it,” Farid continues. “Akrílica belongs somewhere else; it belongs in the hands of those finding one another in a gathering that has yet to take place.” Yet, Matuk seemingly introduces a paradox in the paragraph that follows these lines as he observes that Herrera’s “work as a whole has been excluded from genealogies of experimental or avant-garde U.S. poetry.” This suggests that the collective who came together to republish Akrílica (Carmen Giménez Smith, J. Michael Martinez, Rosa Alcalá, Suzi F. García, hanta t. samsa, and Anthony Cody, along with Matuk), had to contend with how their “own writing practices suffered for passing through sites […] without having encountered Akrílica or a book like it on the readings lists that were handed to [them].” Thus, it would seem that part of the project of publishing Akrílica isn’t stealing it away from anything, but an act of installation: into the institution, the discipline of literature, and traditions of experimental poetics.

Rather than reading Matuk’s statements as antithetical to one another, I focus on how he points to “a gathering that has yet to take place” and suggest that this both means in the past — an encounter with Akrílica that never happened and the Latinx poets who suffered because of it — and a future created by Akrílica. That said, moving into the institution, the discipline, and the traditions of experimental poetics does not mean that Akrílica is institutionalized, disciplined, or traditionalized. Instead, in pointing to a future gathering, Matuk also suggests a future in which Akrílica circulates not only on reading lists, but also “in the hands of those finding one another.” The aesthetics of such a communal exchange informs the collection, which features photos and abstract art in black and white, giving the collection a zine-like feel while also making it easier to photocopy, staple, and pass around.

Each section of the collection enacts the kind of gathering that Matuk points to. For example, in the “Gallery” section, J. Michael Martinez creates what he calls an “infected text.” Responding to how “Covid-19 continues to disproportionately impact Latinx and other communities of color,” Martinez translated the poems in this section “by distributing DNA codons to represent each word in each poem; after, each poem had its own unique dictionary of 64 DNA codons, each codon representing a potential (set of) word(s).” Codons — which, according to a Google search, are “a sequence of three nucleotides which together form a unit of genetic code in a DNA or RNA molecule” — thus speak to the way that Martinez’s translation of Herrera’s poetry creates a genetic code for future Latinx poetry. Moreover, within the context of COVID-19, Martinez’s project illuminates how writing this genetic code is another way to establish Latinx survivance in the face of Latinx mass death from the pandemic, but also from recent events such as the Uvalde mass shooting.

As Martinez’s genetic code makes clear, the collective translated Herrera’s poetry not from Spanish to English or vice versa (though both the 1989 and 2022 editions contain the original Spanish text with its English translation), but riff on the English language poems based on “an impression of the work, an approach that speaks to how the translators see Akrílica.” While such translations can be seen in the grayed-out Martinez poems that appear alongside Herrera’s work, they can also be viewed through the typographical experimentation employed by Anthony Cody in the “América” section. For example, in “Exile Boulevard,” Cody takes the word “float” and has it float in a semicircular, clockwise-pattern, turning upside down before ending with “fall,” thus underscoring how the typography mimics the content of the poem.

Another layer of translation exists in the language of the poems themselves. For example, there is a consistent effort across the poems to make their female characters more agentic. In “Eclipse / Watercolor 41 x 80 / San Francisco,” where the 1989 poem reads, “what woman is being pulled / out of the tombs?” the 2022 version reads, “which woman tears herself from the tombs?” Similarly, such changes occur in relation to feminized labor: in “Concerning the Anti-Theater of Quentino’s Diary” (the 2022 version replaces “concerning” with “about”), “secretaries” is changed to “assistants”; in “Poetic Report on Maids: Toward a Model for Urban Hispaniks in the USA,” the title changes to “Poetic Report on Domestic Works: Towards a Model of Being Urban Hispanik in the US” with all former mentions of “maids” in the poem subsequently changed to “domestic workers.”

Such translations also extend to how the text engages with race. “Arab’s grocery store” becomes “The Arab grocery” in one poem; all references to enslavement are changed to captive (for example, “enslaved salt” in Quentino becomes “captive salt); “plantation” becomes an “estate” in “Minerals in Our Legs.” I’m torn about some of these changes — while making female figures more agentic and not referring to a person as “Arab” make sense to me, changing plantation to estate erases an entire part of history. The full line in the 1989 version reads “biting the plantation of the centuries’ corpse,” which becomes “that bites the ancient cadaver’s estate.” Given the 1989 poem’s dedication to Isabel Alegría and El Salvador, I can only assume that the plantation referenced in the poem is a coffee plantation. Notably, the 2022 version of the poem dispenses with the dedication, which makes me wonder if the shift from “plantation” to “estate” then meant a further erasure of Salvadoran history. The 2022 version also changes the title to “Minerals in the Legs,” which suggests an even bigger shift from the communal “our” to the clinically specific article “the.”

This, then, leads me to my main critique of the 2022 edition, which I offer as an invitation to keep this conversation going. By focusing on the issues that plague latinidad, such as anti-Blackness, which Matuk discusses in his introduction, the translators subsequently erase what the 1989 version of Akrílica did so well, which was express solidarity with Central American struggles, particularly in Nicaragua and El Salvador. As Ana Patricia Rodriguez has shown us, solidarity fictions by Chicana writers have tended to privilege the experience of Chicana protagonists; however, in his poetry, Herrera creates an experimental poetics of solidarity that foregrounds Central American history over Chicanx experiences. Moreover, while the list of translators notes the sections they translated (for example, “Galería/Gallery and Terciopelo/Velvet”), none of the translators actually worked with the original Spanish-language version of Akrílica. J. Michael Martinez’s beautiful genetic code does not exist in the “Galería” section; Anthony Cody’s typography does not adorn and amplify the “América” section.

Most tellingly, women continue to not be agents in the Spanish version, as the line “¿cuál mujer se arranca de las tumbas?” remains the same. Salt is still enslaved; secretaries remain secretaries. But the plantation? It remains “la finca” in Spanish. A finca can never be an estate; it recalls exploited Indigenous labor at the hands of ladinos. The only English word that comes closest to approximating this meaning is — you guessed it — the plantation. Thus, in changing “plantation” to “estate” in the 2022 version of the poem, the translators enact a double erasure: of the Indigenous populations on the finca and of the history of enslavement on the plantation in the United States. Where the plantation reference could have brought together Indigenous and Black Latinxs, the translator’s use of “estate” erases this possibility and, in doing so, participates in the anti-Blackness they hoped to avoid. Further, the dedication in the Spanish-language version of the poem remains intact, suggesting that this act of solidarity can only exist alongside the finca and the plantation, not the estate.

What Akrílica does well is stage a reckoning in terms of both latinidad and aesthetics. Through Akrílica, some of the best poets of our contemporary moment riff and play on Herrera’s work, taking up an experimental poetic heritage that would otherwise be lost. In this way, the collective points to our poetic inheritance as well as the poetic futures made possible by resurrecting Akrílica. Fascinatingly, Juan Felipe Herrera says, in the interview that precedes the collection, that Akrílica “is not the kind of book that would come out today.” And yet, it is a book that is coming out today, albeit in republished form. And, as a book that is coming out today, it illuminates where we are with contemporary Latinx poetics, particularly in terms of how Latinx poetics contend with the political circumstances of our moment and the critiques of latinidad’s investment in whiteness that have been levied by poets such as Alan Pelaez Lopez.

In my own work, I focus on a latinidad that is not yet here, and in Matuk’s introduction, I find him calling for that future latinidad and calling on Herrera to help us realize that liberatory future. However, by privileging Latinx experiences that are bounded by the English language and not also experimenting with the Spanish-language poems, the translators missed the opportunity to install the kind of hemispheric latinidad Herrera points to through his solidarity with Central American countries like El Salvador in the 1989 edition. That said, the 2022 edition of Akrílica is a remarkable achievement that illuminates the work we have to do to build “a gathering that has yet to take place.” In other words, rather than canceling latinidad, which would not compel the kind of reckoning that both the 1989 and 2002 versions of Akrílica encourage, we should think about how our decisions about Latinx poetics reflect our investment in Latinx politics. In doing so, we can see not only how far we’ve come, but also what work remains to be done. While I am drawn to Matuk’s distinction between recovery and retrieval, we must remember that the two words are synonyms of each other, a kind of slant rhyme that encodes the work of retrieval in recovery and vice versa. In retrieving the Spanish-language poems, I think, we can recover a latinidad that is not yet here in a gathering that has yet to take place.

¤

LARB Contributor

Renee Hudson is an assistant professor of English and director of Latinx and Latin American studies at Chapman University. A former University of California Chancellor’s Postdoctoral Fellow at UC San Diego and Institute for Citizens & Scholars Career Enhancement Fellow, Renee is the author of Latinx Revolutionary Horizons: Form and Futurity in the Americas, out in 2024 with Fordham University Press. She is currently working on a second project on Latinx girlhood.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“Our Energy Is the Epilogue of Empires”: On Angel Dominguez’s “Desgraciado”

Renee Hudson considers “Desgraciado” by Angel Dominguez.

The Holding Places of Impermanence: On Adalber Salas Hernández’s “The Science of Departures”

Shannon Nakai travels through “The Science of Departures,” a book of poems by Adalber Salas Hernández, translated by Robin Myers.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!