The Holding Places of Impermanence: On Adalber Salas Hernández’s “The Science of Departures”

Shannon Nakai travels through “The Science of Departures,” a book of poems by Adalber Salas Hernández, translated by Robin Myers.

By Shannon NakaiJune 2, 2022

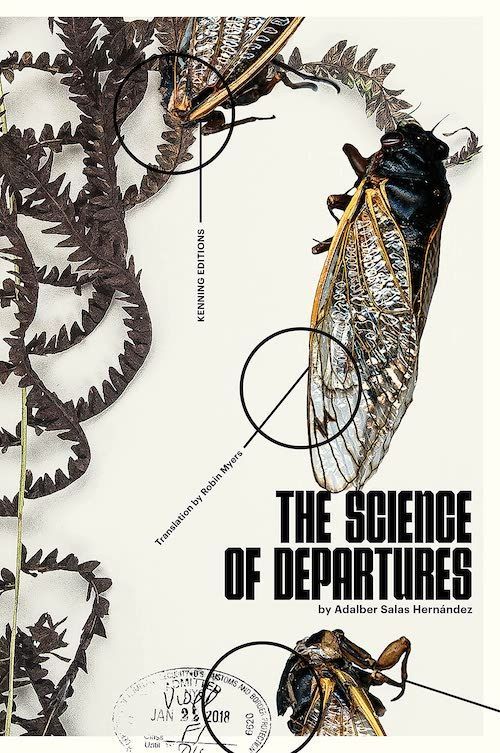

The Science of Departures by Adalber Salas Hernández. Kenning Editions. 160 pages.

ADALBER SALAS HERNÁNDEZ’S latest collection, The Science of Departures (La ciencia de las despedidas), translated from Spanish by Robin Myers, offers a profound sociocultural study and incisive critique of the different departures that mark our existence. Human activity is neither stable nor neutral, and Salas Hernández’s expansive cast includes tourists, migrants, slave ship drivers, martyrs, ex-lovers, biblical figures, mythic legends, ghosts, government officials, archeologists, and a speaker whose medical papers identify him as Adalber Salas Hernández himself. Sometimes a child, sometimes a man, this speaker reckons with each exit as a reminder of mortality. In the poems, he is eating, loving, hurting, traveling, remembering, and dreaming before a grim audience: rats that will one day consume him, the deceased who have surpassed and now observe him, god(s) that confuse(s) him, and blood that teaches him of humankind’s ability to wound and be wounded. Here we are confronted with the cycle of remembering and forgetting — of leaders, lovers, fathers, and daughters who appear and one day fall away. Ultimately, Salas Hernández asks us to consider what we make of ourselves in such a confined, transient existence.

The front cover bears cicadas that recall the mythic figure Tithonus, a man who suffered endless time without youth due to the innocent request of his lover, the goddess Eos. In an indictment against the destructive power of divine love, Salas Hernández’s opening poem, “One-Way Ticket” (“Pasaje de ida”), recounts a similar suspension of time:

We study the departure screen and the

next flight

and the next

and the next,

each taking off with the same

deaf precision, like obedient children,

fearing the divine and punishing hand.

Miramos la pantalla de salidas y el

próximo vuelo

y el próximo

y el próximo,

todos despegando con la misma

precisión sorda, como niños obedientes,

temerosos de la mano divina que castiga.

He likens airports to hospitals; both are temporary holding places he views with circumspection. Awash with artificial, immaculate light, they receive and transport bodies and their accompanying papers. At one point, he demands to know:

who designs these entry forms, who selects

the ticket font and size, who

instills them with their taste for getting lost?

¿quién diseña estas planillas de ingreso, quién escoge

la tipografía de los boletos, su tamaño, quién

les inculca esta inclinación a traspapelarse?

Each poem alludes to movement, specifically its deliberate one-way direction: time, age, loss of innocence, and loss of self and language in relocation. Salas Hernández tells us, “We travel: space is what foretells us” (“Viajamos: es el espacio que nos deletrea”). He sustains the motif of movement, of traveling in particular. Though the speaker compliantly offers up his passport and his medical papers, he is far from passive. He is equipped with words:

in the places where no one speaks my language

the body is a disappearance: there’s a

transparency that suddenly grangrenes my

flesh, no syllable can restore me, no one

can see me. But I don’t travel without a suitcase.

My city is made of paper. I can fold

it up and stuff it in my pocket;

it’s shaped like a notebook, like a knowing

touch.

en los lugares donde nadie habla mi lengua

el cuerpo es una desaparición: hay una

transparencia que gangrena de golpe la

carne, ninguna sílaba me carga, nadie

puede verme. Pero no viajo sin equipaje.

Mi ciudad está hecha de papel: se

dobla y se guarda en el bolsillo,

tiene la forma de un cuaderno, de un

tacto cómplice.

Assertive, proclamatory, many poems open with a statement, a pronouncement, or a truth: “It’s common knowledge: fish don’t talk” (“Los peces no hablan: es bien sabido”); “I’ve never been to Tübingen” (“Nunca he estado en Tubinga”); “It’s a strange thing, a shadow” (“Es cosa rara, la sombra”); “It took me years to discover that snow / is the least loving form of sleep” (“Me costó años descubrir que la nieve / es la forma menos amorosa del sueño”); “Odysseus never returned to Ithaca” (“Odiseo no volvió a Ítaca”). This last line begins Salas Hernández’s reimagining of Odysseus as a displaced man stripped of home, family, and history. Without papers to document his origin and home country, Odysseus becomes a living ghost. He cannot lay claim to any possession that would grant him roots, not even his language. “He tried to explain / that traveling means language lost, not gained, but / it was all for naught.” (“Trató de explicar / que viajar es perder lenguas, no ganarlas, pero / fue en vano.”) In a later poem, “XXII,” he negotiates a language “made of faulty / questions, of cropped, repeated phrases” (“hecha de preguntas / defectuosas, de frases truncas, recurrentes”) that inevitably escape him.

My language has never been able to resemble

itself. It’s made of words that say

goodbye as soon as they arrive.

Mi lengua nunca ha sabido parecerse

a sí misma. Está hecha de palabras que

se despidem apenas llegan.

Later on, he catalogs two lists of words, one reminiscent of picture-book vocabulary, and the other a weightier, violent list that exchanges innocence for experience:

Simple words: rain, sun, house, tree, road, mother,

father, brother, laughter, now, animal, fear. Simple

and dependable as fingers. Complex words: name,

number, blow, shout, question, bullet, accusation, past,

future, patience, animal, fear.

Palabras simples: lluvia, sol, casa, árbol, calle, madre,

padre, hermano, risa, ahora, animal, miedo. Simples

y confiables como dedos. Palabras complejas: nombre,

número, golpe, grito, pregunta, bala, acusación, pasado,

futuro, paciencia, animal, miedo.

Even the words he designates as simple — “mother,” “father,” and “road” — reappear elsewhere in the collection as complicated, even malevolent constructs for which a poem can offer no resolution. “Animal” and “fear,” the most primal building blocks, reside in both lists of what is simple and complex.

In The Science of Departures, impermanence itself becomes movement: there is no fixed place anywhere at any time. Even death is impermanent: the severed head of John the Baptist still speaks, Lazarus blows up Twitter feeds, and corpses rise from the dead to organize agencies and protect their rights as citizens. The body is a vessel that carries itself from one violence to another, blood “conveying / its belongings, its concrete contraband” (“llevando / sus pertenencias, su contrabando de cemento”). The body is also a landscape for primal wildness, blood “made of / horses straining to be free” (“hecha / de caballos ansiosos por escapar”). At the mercy of hunger, assailants, social media, and online porn that “have monopolized the market / of intimacy” (“han monopolizado el mercado / de la intimidad”), the body is laid to waste in a world with many witnesses yet few intercessors. Salas Hernández’s speaker is both; he seamlessly shifts from an unapologetic indictment of an anonymous government minister in his biblical retelling “A Day in the Life” to a tender plea for protecting the innocent in “Lullaby for Malena” (“Nana para Malena”).

Paradoxically, in an existence marked by departures, there is no end in sight. As Salas Hernández grimly suggests, “Boredom is the only thing that resembles / eternity: it labors with an honest love for detail” (“El tedio es lo único que se parece / a la eternidad: hace su trabajo con genuino amor por el detalle”). In “Burnt Norton” (1936), T. S. Eliot writes, “Time past and time future / Allow but a little consciousness. / To be conscious is not to be in time / But only in time can the moment […] / Be remembered.” Salas Hernández responds, producing a hollow-man observer for whom “the past / couldn’t be the future and time was just / the country of what has already been seen” (“el pasado / no pudiera ser el futuro y el tiempo apenas / fuera el país de lo ya visto”). Instead of Eliot’s whimper, Salas Hernández offers the silence of the dead: “A bus in the middle of the highway. That’s how this ends.” (“Un autobús en medio de la carretera. Así termina esto.”) The violence is reckless, almost meaningless, as a bus of anxious migrants becomes yet another bloodstained site in the landscape of constant suffering and cruelty. Adalber Salas Hernández presses his reader to consider the cost of a final departure from an existence marked by the perpetual posture of cowering. Are we, as his speaker claims in “Natural History of Debris: Kidneys”:

Creatures without

witnesses, living far from the

rabid empire of the gaze.

They fear discovering the coast of this

subterranean sea, its naked

and dazzled shore, zenithal knife.

Beyond the skin, the light:

the most finished form of fear.

Criaturas sin

testigos, viviendo lejos del

imperio rabioso de la mirada.

Temen descubrir la costa de este

mar subterráneo, orilla desnuda

y encandilada, cuchillo cenital.

Más allá de la piel, la luz:

la forma más acabada del miedo.

But Salas Hernández does not offer us an absolution for what lies on the shore, the other side. Instead, in “Dubia et spuria,” he grants us an ecclesiastical observation of the enigmatic cycle of life, a pronouncement for preparing for departure and the implication of how we handle ourselves, our vulnerable citizens, and this world, itself a temporary and frequently used holding place:

To live life so that it’s left

intact when we leave it,

so that someone else can pick it up

off the ground, stretch it out, dust it off, wear

it loose. To drink our water, yawn

away our boredom, laugh at our second-

hand ironies. As far as life is concerned, continuity

and plagiarism are one and the same.

Vivir la vida de tal manera que quede

intacta cuando la abandonemos,

para que alguien más pueda recogerla del suelo,

estirarla, sacudirle el polvo, vestirla con

holgura. Beber nuestra agua, bostezar

nuestros aburrimientos, reír nuestras ironías

de segunda. Para la vida, continuidad y

plagio son una misma cosa.

¤

LARB Contributor

Shannon Nakai is a poet and book reviewer whose work has appeared in The Cincinnati Review, Atlanta Review, The Literary Review, Tupelo Quarterly, Cream City Review, Image, Cimarron Review, and elsewhere. A Fulbright Scholar and Pushcart Prize nominee, she currently lives with her husband and children in Wichita, Kansas. Follow her on Twitter @shan.violinlove.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Resistance and Rhetoric in Susana Thénon’s “Ova Completa”

The Argentinian feminist poet had a harsh, yet oddly hopeful, view of humanity.

On Cosmopolitanism and the Love of Literature: Revisiting Harold Bloom Through His Final Books

Ignacio M. Sánchez Prado looks back on the work of Harold Bloom.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!