I’ve Always Stood in My Truth: A Conversation with Yesika Salgado

Daniel Lisi talks with Yesika Salgado about the fifth anniversary of her breakout poetry collection “Corazón.”

By Daniel LisiDecember 17, 2022

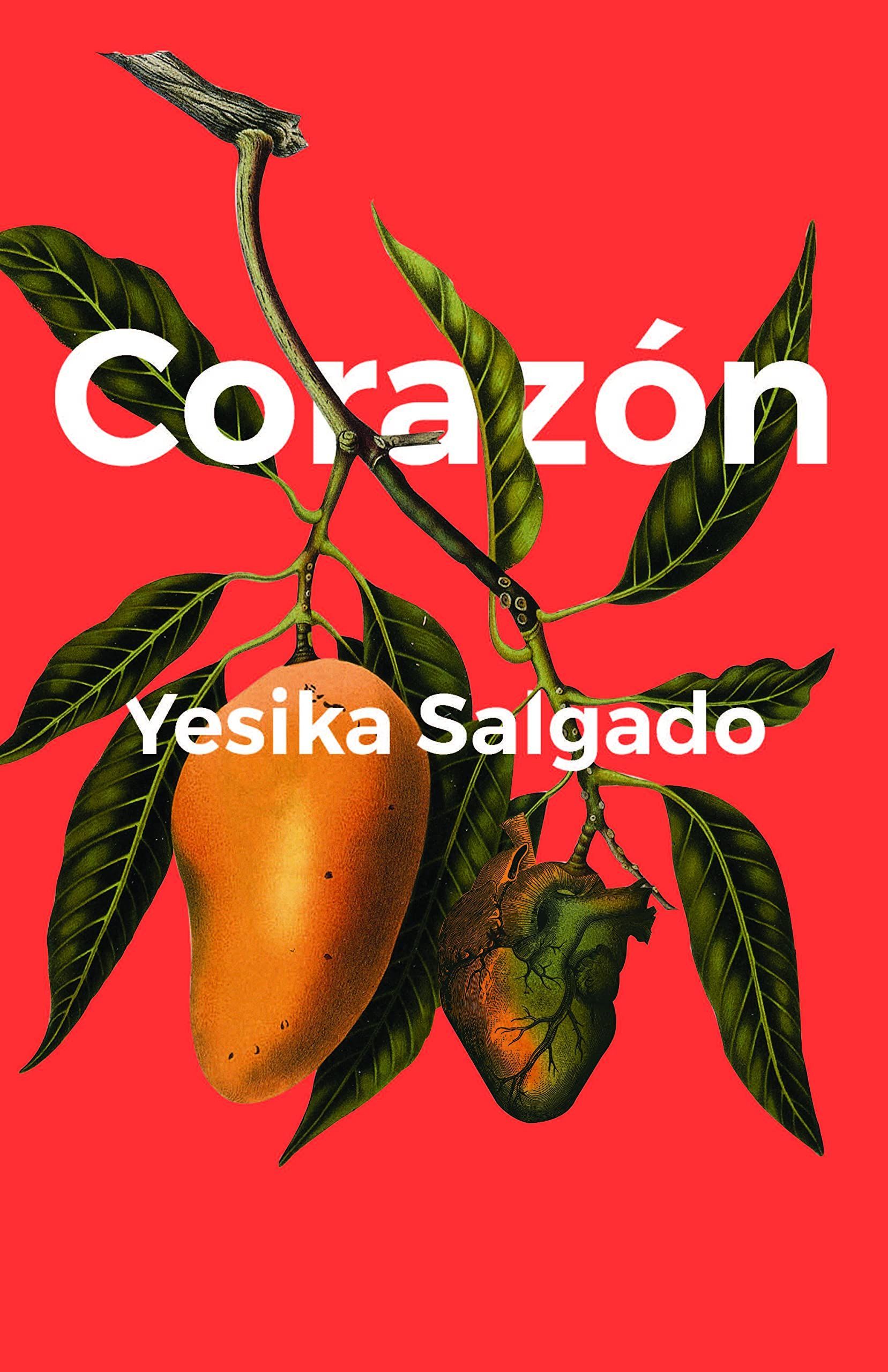

Corazón by Yesika Salgado. Not a Cult. 86 pages.

WHEN CONSIDERING Yesika Salgado’s success, we can’t help but think about the spectrum of gatekeeping that controls publishing and distribution in the book trade and how Salgado curtailed this process by cultivating something entirely original: a mercurial X factor that platforms generally only notice after it is too late, the trend trending. It was a cosmic dart-throw that our paths crossed just as Not a Cult emerged into publishing. If Not a Cult had not signed Salgado’s debut title Corazón in 2016, another publisher would certainly have capitalized on the wave Salgado was creating, the foundation she had started laying down far before anyone took her literary force seriously.

Salgado’s skills combine crafty, innovative poetics and silky, enrapturing oration. These dual forces are what break poets out of niche corners and make them wildly influential leaders of a community. Salgado defies narratives of fatness and femininity that percolate through the mainstream, interweaving them with stories of heartbreak and family. She has seized a power of reclamation over her own personhood as a fat Brown woman in Los Angeles — a city that, perhaps, hates fat Brown women.

In 2013, I was working as the media manager for PEN Center, where I focused on creating readings in Downtown Los Angeles. I wanted to create a vehicle that touring authors could tap into when visiting our city, so I began a series called “The Best.” Around 2015, as hollis hart and I were starting to piece together a catalog of books we wanted to publish that would later become the beginning front list for Not a Cult, I became interested in what was emerging from Da Poetry Lounge, the largest open mic in the country, staged at the Greenway Court Theatre on Fairfax. DPL featured a group of poets that comprised L.A.’s official slam team, which would get sent to the annual (now defunct) National Poetry Slam. In this group were Alyesha Wise, Matthew “Cuban” Hernandez, Tonya Ingram, and Yesika Salgado. I booked events with this group, as well as with each of these poets individually. None of them yet had books. After doing shows with all of them, I offered a publishing deal to the DPL cohort for the emerging Not a Cult list.

Salgado’s Corazón was released a year later on November 6, 2017, making our first front list a national breakout success. The book sold 15,000 copies within a couple of months, landing Salgado on bestseller lists. The release event staged at Art Share L.A. went far beyond capacity because Salgado’s presence was already known. This began a three-year sprint during which she worked tirelessly to produce a three-book series, as we challenged each other and ourselves to grow from project to project. That period in our lives was incredibly formative and powerful, but perhaps unhealthy in other ways, as we contended with the pressure to continuously pump out content.

Five years later, we are significantly older and wiser.

¤

DANIEL LISI: So, we’re coming up on five years of Corazón.

YESIKA SALGADO: Five wild years.

Five whole wild years. As we previously touched on, this is definitely not a conversation about the future. This is a conversation about what has happened. Because it’s been an extraordinary time. That release event we had at Art Share, the pandemonium of it. How unprepared we were just in terms of the scope of audience, right? That was a pretty special night.

Yeah, and you know the funny thing about that? I don’t know if I ever told you this, but it taught me to advocate for myself and for my community a little bit harder. Because I think leading up to that, you and I were still getting to know each other — we didn’t know my readership yet, because Corazón wasn’t out — but I remember I told you, “I think we need a big space.” And we had aimed for, like, a warehouse, and it didn’t work out. And then I thought, No shade to Art Share, but — it was just — I feel like we need something bigger. And then, when it didn’t work out, and you said we’re gonna be there anyway — I’m just grateful to have a space, right?

And then what happened, and the way that it happened, and the pandemonium of it, I think it was a lesson for myself and anybody else that was there, how I wasn’t arriving anywhere. I was already there, you know? And I was treating it very much as — I felt like I was asking you permission for things instead of telling you what I needed. But that’s just about who I was as a person then and the growth I hadn’t pushed myself into and all that. But I think that day was a day when I was as well intentioned as anybody can be; nobody will know my readership like I do. Nobody will know my mangos like I do, and it’s my job to push when someone else doesn’t understand. Because it’s not a bad thing if somebody doesn’t, but nobody else will know how people turn up for me other than me, because I’m the one that sees them everywhere.

Right, big time.

I mean, and we together have grown so much from that, and now we know what to expect for events now. But I think, at that point, I always credited large turnouts to other people, to other things. And I was just, you know — Chingona Fire was a thing at the time, so all the people that would come out, I would think, “Oh, it’s not for me, it’s not for Angela, it’s the open mic.”

I see. You didn’t think that it was your influence, right. Yeah, I would say that that was apparent to me, because when we were starting Not a Cult, even before the publisher was set, we were doing events pretty frequently. And Art Share was just comfortable for me because that’s where I had been running those productions, at least for a couple of years before any publishing activities.

Yeah, you had invited me to perform before.

And that was the big thing that we noticed, right? That when you were booked, you were packing in audiences, and that was a big signal to me to build a poetry catalog seriously, that we have these audiences here, these amazing authors drumming up really enthusiastic crowds. There’s clearly something going on here. And yeah, that was just proven twentyfold when the book came out.

I wouldn’t change that night at Art Share. I wouldn’t change it at all. Sometimes I think, What if I had a bigger venue, what if I had been more thoughtful about the event and poured more into it, blah, blah, blah. But no, the way it happened was the way it needed to happen for everybody involved.

And I don’t think it hindered the book in any sense.

No, I just remember the day of, I was upset because I remember they weren’t letting anybody else in. I had family members that couldn’t get in. And I had an uncle that wasn’t let in, and he was sitting outside. And I remember being so upset. But the event had already started, there was no way that I could flag you down to let you know. So, I just sat back down and thought, well, it’s his fault for being late. But also, he was the biggest naysayer about me quitting CVS and becoming a full-time writer. And so, he had to sit his ass outside and watch all of the mangos waiting eagerly to just see me for a second. He saw girls crying, leaving crying, just moved afterwards when it was over and all of that, and I think that moment showed my family and me what I had built and hadn’t paid attention to.

Because I always gave the rest of the community credit. Not to say that the rest of the community doesn’t deserve credit. But if we had a show, I would have said to myself, “Oh, a lot of people are here because x, y, z are also headlining with me.” You know? Like you find ways to talk yourself out of being the person that does that. And I think that the Corazón release was just, like, girl, look! And it felt like a homecoming for me. It was one of the most surreal nights of my life. And even when I still think back to it, it feels like a fever dream.

And that’s a good segue into thinking about ourselves in 2017 versus now in 2022, with regard to priorities. I’m interested to hear how your priorities have evolved — in a creative sense, a professional sense, and a personal sense.

I think there’s one umbrella that covers all of that, and I’ll go specifically into each one.

First, I’m not trying to prove that I’m a writer anymore. And I feel that a lot of the things that I was doing in 2017 were desperately trying to get validation that I was headed in the right direction. I had left my job; I had taken the dive, and didn’t really have much of a plan, and had been toying with the idea of turning my chapbooks into a full-length book, and I was a very scared person then. And I think that fear was good, because I was so afraid that it made me fearless in my actual work. Because I was so worried about the logistics of everything that I was relieved to just be able to write.

And so that’s who I was in 2017. But now, in 2022, I’m much more calculated. Or maybe I should say selective. I move a lot slower than I used to, on purpose. And I think my storytelling is still — I’m still talking about a lot of the same things, but I feel like I’m giving the story more grace now. I think that I used to write — I was still trying to heal from a lot of things that I had survived until that point, and now I’m not just on survival mode anymore. Now I’m kind of comfortable. But I think that, creatively, that sometimes stumps you. Because I’m not writing from that hunger anymore. And so now, inspiration is a little slower to come. It’s wild, and comparison is the thing that keeps happening. But I think I deal with it a lot better now than I did.

Comparison in what sense?

Comparing myself to everybody. Especially because a large part of my work exists online, I’m constantly looking at other writers and other people, and I’m just thinking I never get tapped in for anything, or I’m never going to be on that, and I think I was starting to do a lot of that. And then, you’ve been somebody that always reminds me that the work I’m doing is different.

Well, it’s easy to remind you, because I am seeing the day-to-day results of your books out in the world.

I think, because I grew up seeing poetry look a specific way, and a lot of my peers went the MFA route or were submitting constantly to things, and those were all things I had no experience in, I told myself I was behind everybody because I didn’t have all of that. But now I’m glad I didn’t go that route. Because my work is a part of L.A. culture forever. And beyond L.A. And I feel that’s a place where I’ve arrived, where what I’ve built, what I have, is undeniable. I might never write another book again, and already I’ve created work that is going to continue interacting and speaking to people. I mean, I don’t sit in that knowledge every day. I don’t walk around the world like that [except] when I need to remind myself, you know?

One thing you told me once, and I tell myself all the time, is that numbers don’t lie. And being a woman with all of the intersections that I have — being a fat woman, being a woman of color, being a high school dropout, being a disabled person — all of these things and their intersections, I used to think I was being punished for them. But what I have built is undeniably mine. And I’ve done it completely on my own terms, so that no one can ever be surprised when I do some very Yesika thing, some unhinged thing somewhere, and they’re just like, yeah, that sounds like her. And I really appreciate the transparency, and just how I’ve always, no matter what, for better or worse, stood in my truth. That’s the best thing.

I would argue that the job of the poet is to be that kind of unfiltered, true, and beautiful example of whatever it is you’re talking about. And so, that’s inspiring to hear, and I think you’ve absolutely achieved that in your career. And I’m glad that you’re being more selective as you continue making things.

The beauty of being so much more intentional is that everywhere I’m at is somewhere I want to be. Now I get to say yes to things that I’m passionate about. A group of lawyers who do pro-bono work for a nonprofit recently asked if I would perform for their volunteers. And the rate is way beneath what I would charge, but I can say yes to that because I’ve made it a point to get other jobs that pay me my worth. And so now I’m not feeling like I’m scrambling for something, and that’s really — it makes me feel powerful. I can honestly tell whomever I’m choosing to work with that I’m working with you because I believe in you. I’m working with you because I believe in what’s happening here. Instead of being like, well, you brought me out here.

There’s a lot of power in where you choose to invest your energy. That is a really important position to have, being able to make those choices.

And that’s a huge responsibility, too, to know that there’s folks, you know, my mangos, my cosign means a lot to them. So I have to be incredibly careful. I reach out to you sometimes to say, “This feels fishy,” if there’s an inquiry about something or a person, and I can’t say yes, because it might end up being something harmful, and then people are going to doubt my integrity. And that’s important for me. And so, there’s that too, that balance to be a person for the community but also not let your community take advantage of you. And that is hella real. Because I have a level of sensibility that people expect me to say yes to so many things. And I want to, but physically I can’t.

You’re also a human being who wants not to be traded as a commodity every other week, you know?

Yes, there’s a lot of that. But yeah, it’s a dance. And I’ve gotten really good at dancing. I think I was learning the steps in 2017. I had to quit CVS where I had been working for three years, and before that I worked in a parking lot, so I’ve always been a person who works over 40 hours a week. So, to walk away from that and say, “I’m going to be a writer” — well, I was always a writer. But to try and make an income just from writing — it was terrifying. Because I didn’t know anybody like me who did that. And I knew other people who were similar but were trying to figure it all out, and then you showed up. “Here, let’s do a book,” and I say, “Sure! This is great. You’ve published my friends.” And it was lightning fast, right?

Yeah, it was. Especially in those early days when we didn’t have a formal distributor. So, it was much easier to say, “We have this idea; we’re going to put out this book and do it on our own timetable.” But then the two books that followed, it was an extremely fast process. Specifically for you, developing those manuscripts.

I remember. I remember finishing Corazón, just having the book release, and me telling you [that] I’m ready for the next one. And you were like, “Take a second, we’ll have a meeting. I’ll send you the contract, and you’ll sign.” And then that’s when Tesoro came out, a year later, right? And we took on the big adventure of having a produced show for that.

Right, yeah. At the Lodge Room.

And that’s what I’ve loved about our partnership, that there have been many times I’ve come to you and said, “I have this idea.” And then you take a second to figure it out, and you come back and you say, “How about we do it like this? Cool, let’s do it.” We did that with Tesoro. We did that with the Valentine’s Day show we had.

That was maybe the first time that I figured out how to invest capital in a show to make sure we at least recuperate. That was extraordinary. It was so much fun. And it really set us up for Hermosa, working with the Los Angeles Public Libraries, the Central Library. I was really grateful for that experience, because that was full-on event production — which, between 2017 and 2019, we did so much of.

That period was a sprint in a lot of ways. And there were a lot of cool, positive results from that. But it was a lot. It was a lot of constant work. And then, 2020 hit with the pandemic, and we were fresh off [of] a New York trip, so late 2019 was spent doing events for Hermosa. And that was the first time that we had taken this out of state and were doing New York shows. And that was simultaneous to us moving into Junior High’s Hollywood location where we had all of these programming concepts. And then March hit, and the world changed.

Yeah, I mean, we were just doing a workshop right before everything shut down.

Literally, a week before …

That was the last group of people we were with. And I think that was the part that I loved, that we had so many events that my readers recognized your face. You know, they knew what Not a Cult looked like. And also, another one of my joys has been that I’ve been able, through this process, through these five years, to share my audience with other people I really believe in.

To be able to do that with Karla Cordero has been the biggest thing. To the point where we did our own little digital tour together — our Zoom tour. And there’s so much that we want to do together that will probably happen in the future. You know, Sheila Sadr and Rhiannon McGavin — I mean, Rhiannon is her own powerhouse. But to be able to have events where they cross over, or have my readership fall in love with other voices from L.A.

And what I love so much about Not a Cult is that it’s so L.A. I can easily — if anybody ever asks, “Who are your favorite L.A. writers?” — tell them, “Just google ‘Not a Cult,’ look at the catalog, and choose whoever you want.” And that’s my favorite thing, too, to sell my friends’ books. Because people will come up to me at events and say, “I already have all three of your books.” And I’m like, “Yeah, but do you have Edwin Bodney? Do you have Karla Cordero? Do you have these people who are phenomenal writers in their own right?” And that’s been really exciting, too, to know that what we’ve built is a community thing.

I would say that, out of the three books we’ve done, Hermosa has had a certain level of prestige over the others, for whatever reason. They all communicate with each other to some degree, but Hermosa won the 2020 International Latino Book Award in its category. We’ve also experienced the books going through the university scenes. Corazón in particular has been on a number of college and university curricula. But the thing that is new to see happen is Hermosa getting adopted into New York City high school curricula.

That’s wild to me. Especially because some of the poems …

I was thinking about some of the poems, right. I was thinking, some of these kids are about to learn about …

Eating ass.

Eating ass, yeah. And so, hilariously enough, I’m curious to hear what you hope teenagers walk away with from encountering your body of work. We were talking about this before we started recording: you had said something like, “How do you know if your books are still going to be relevant to young people?” And, well, here’s the answer: young people are being taught your books. So, I’m curious about how that makes you feel, knowing that so many teenagers are going to be experiencing your work in an English class setting. I mean, just thinking about my own high school English experience, if I had had access to your work then, I can’t imagine how that would have colored my entire perspective on poetry. So, I’m curious to hear what you hope gets imparted to these youths.

What I think of when I think of high school kids is myself at 17 going through my first heartbreak, going to class, swollen eyes from crying all night, and Mr. Seles, my history teacher — who was Chicano, which I don’t think I understood at the time — came in one day and handed me a copy of Sandra Cisneros’s My Wicked Wicked Ways — or Loose Woman. I always forget which of the two it was. And he said, “I have a feeling you’re going to like this book. You can borrow it for the rest of the semester.” He wanted it back because it had been signed by the author. And so, I read it, and immediately some part of my brain just freaking opened up. I think I had come across The House on Mango Street before and had loved it and enjoyed it, but I never understood that it had come from something specific, from someone’s experience. I don’t think I ever made the connection to Sandra like that.

There was something about those poems, the way they showed up in my life at a moment when I was grasping for something. When I was 17, I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. My father was an alcoholic, and we were bumping heads a lot, because I was old enough to understand that some stuff was abusive or endangering. It was just this really chaotic period. And I think of the fact that high school students now are going through all that, what I went through. And all of a sudden, there’s me, this girl who felt incredibly weird and unseen at that age, writing about feeling incredibly unseen and unloved and all that, and these kids are going to read those poems …

And they’re going to read Hermosa — which, if I had to pick a book out of the trilogy, is my favorite. Tesoro I’m very protective about in certain ways, because of its subject matter. And Corazón is my firstborn. She’s gonna make me proud all the time, but I think Hermosa is the book that I wrote for myself. I always write in a vacuum. I don’t really share my work with other people until it’s finished, because I don’t want to let other voices get into my head. With Hermosa, I remember I kept extending the deadline. And I kept thinking the book was never going to come out. And I was crying about it at lunch with my friend Gabby Rivera, who’s also a writer, and Gabby said, “I haven’t seen this Yesika yet. The lipstick and nails, and poet … like, you’re not trying to convince anybody that you’re a writer anymore. You’re Yesika Salgado.” And so, then I went home, and I was like, “Alright, let’s get it done!” These are all my favorite poems. And so, it makes me proud that Hermosa is the one that’s being studied in schools, because it’s the one where I showed up more as myself than in any of the other books.

The original intention was that it was going to be this epic ode to Los Angeles. And there are still elements of that, but it definitely morphed into an extremely Yesika Salgado book as well. An ode to your own voice as much as to Los Angeles, which obviously was an incredibly powerful alchemy that ended up taking place in the manuscript.

And it’s the most L.A. cover, with the jacaranda. It’s the Lakers colors, you know? I mean, this is as L.A. as it gets. And I think what I want kids to understand, to circle back to, is that there’s space for everybody. That’s corny. Everybody says it, but I don’t think we truly believe it — that there’s space for everybody’s story. And if anything, I’m proof of that. Because I’ve come into an industry that hates, really hates it, when you don’t pander to the institutions. I mean, like, Rupi Kaur is an example, right? Some folks don’t like her work, some folks do, but a lot of the time it’s not even the work that’s in question. It’s about whether she’s worthy of her audience or not. But it’s not our job to decide whether the writer is worthy of the audience.

It’s so audacious, to do that kind of gatekeeping. I mean, who are they to question the obvious impact that draws hundreds, thousands of people to a space?

What I’ve learned is that when your audience is mostly women, it will be discredited. It will be turned into something frivolous and unimportant, and the younger the women in your audience are, the more they get dismissed.

You know, I’ve been called a niche writer. And I’m like, niche, where? I sell globally, and my numbers are on par with people you wouldn’t consider niche. So, what is it that makes me a niche writer?

I mean, I’m not here for validation from other poets, from other writers. I’m in community with a lot of them, and we love each other’s works, and it’s beautiful, but they’re not who I’m writing for. At the end of the day, the reason I continue to share my work online in the way that I do is because I want it to be accessible to whoever needs it. And it might be the teenager who might not have the $16 to go to the bookstore and get the book, but they can scroll down my Instagram, or listen to the poems, or read the poems, or whatever it is that they want, and share it with their girlfriends.

And you’ve been there for all the events where rows and rows of women are weeping. Some of them with their moms, with their sisters, with their best friends. That, for me, is the most sacred thing. When somebody brings their mom to my shows, or when they bring another family member, or when best friends tell me, “We send your poems to each other” — the fact that I get to become a part of those relationships in some way is so special to me.

And knowing that a lot of queer kids, too, relate to my work, to the idea of feeling unseen so much. That’s always the core. My job is to provide a mirror for those looking for their own reflection. And if you don’t see your reflection in me, that’s fine. But for those who are looking for something that speaks to them like that, I’m here.

¤

LARB Contributor

Daniel Lisi is the cofounder of Not a Cult, a book publisher based in Los Angeles. He’s a producer spanning film, television, VR, and print media. He sits on the board of directors for community arts nonprofits Art Share L.A. and Junior High Los Angeles. Photo by Jazzy Harvey.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“Poetry Is a Superpower”: Edward Vidaurre and FlowerSong Press

Dick Cluster profiles the Los Angeles–born, Texas-based small-press poet and publisher Edward Vidaurre.

“A Drive for Beauty”: A Conversation with Daniel Lisi and hollis hart, the Co-Founders of Not a Cult Media

Yesika Salgado speaks to Daniel Lisi and hollis hart, the co-founders of Not a Cult Media.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!