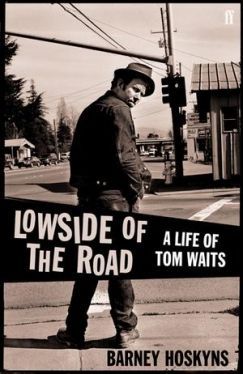

Lowside of The Road by Barney Hoskyns. Three Rivers Press. 640 pages.

DURING THE FIRST, formative decade of his career, when he was largely based in Los Angeles, Tom Waits mined a rich seam of the city's lowlife locations and noir associations. Right from the outset, Waits liked to mix the domestic with the mythic, turning his own quotidian details into something far darker and more emblematic. Waits's famed residency at the Tropicana Motor Hotel managed to combine both these impulses. “There is a kidney shaped swimming pool in the courtyard,” William Burroughs wrote in Rolling Stone in 1980. “On the patio are rusty metal tables, deck chairs, palms and banana trees: a rundown Raymond Chandler set from the 1950's. One expects to find a dead man floating in the pool one morning."

This pleasingly named, deeply unsanitary West Hollywood motel featured as the main location for Paul Morrissey's film Andy Warhol's Heat (1972) and was already renowned for its cool sleaze by the time Waits checked into his two-room apartment in 1976. There, half-buried under his stash of records, girlie mags and empties, Waits exhibited a semi-public enactment of his stage persona, a version of the Beat musician in tune with the poetry of the streets. The ungovernable state of his room became part of the legend. Barney Hoskyns, in his excellent biography, Lowside of The Road, quotes a friend of Waits's, who opened the fridge in search of a beer, and found only "a claw hammer, a small jar of artichoke hearts, an old parking ticket and a can of roof cement." It even sounds like a line from one of Waits's spoken-word poems of the time.

Waits had formed a small bohemian circle, which moved from the Tropicana to sober up over coffee at Duke's and spent their nights at the Troubadour. Waits's main sidekick and conspirator was Chuck E. Weiss, a good time guy originally from Denver who loved his drugs and tall tales. Made famous by Waits’s one-time girlfriend Rickie Lee Jones's serenade, Chuck E. also received a Waits tribute in the track “Jitterbug Boy” (from Small Change, 1976). The song showcases one of Waits's fondest early personas, that of the buttonholing boozer, bending your ear with ever more outlandish stories, and has the extended subtitle “Sharing a curbstone with Chuck E.Weiss, Robert Marchese, Paul Brody and the Mug and Artie.”

This is the high watermark of Waits's self-mythologizing Los Angeles legend, the time he deliberately set about living the life his songs described. In 1982 he told Dave Zimmer of Bam:

I really became a character in my own story. I'd go out at night, get drunk, fall asleep underneath a car. Come home with leaves in my hair, grease on the side of my face, stumble into the kitchen, bang my head on the piano and somehow chronicle my own demise and the parade of horribles that lived next door.

Out carousing with his boys all night, attracting female admirers who would camp out on the porch of his bungalow and wait for his early hours return, Tom Waits started to resemble "Tom Waits":

When I moved into that place it was nine dollars a night. But it became a stage, because I became associated with it. People came looking for me and calling for me in the middle of the night. I think I really wanted to kind of get lost in it all and so I did.

It wasn't just that Waits’s lush life had turned into a kind of prison. His performing persona had hardened into a mask, one that restricted his musical growth. His characteristic reworking of spoken Beat idioms and jazz-blues rhythms, his portraits of Americana, with its diners and drunks, had become repetitive, a self-created trap, bound up with his complex relationship with his alcoholic father.

Hoskyns makes clear that what lay behind Waits’s compulsive need to re-invent his own past until it became self-creation ("I was conceived one night in April 1949 at the Crossroads motel in La Verne,” he claimed in concert, “amidst the broken bottle of Four Roses, the smoldering Lucky Strike, half a tuna salad sandwich...") was his father's desertion. That was the crucial catalyst for Waits’s desire to portray himself as the whisky-soaked crooner par excellence, raddled beyond his years.

Jesse Frank Waits (named after the outlaw James brothers), a Spanish teacher, would drive Tom from their safe, middle-class Los Angeles suburb of Whittier down to Tijuana, over the Mexican border. “My Dad taught Spanish all his life,” Waits told Hoskyns for a 1999 Mojo piece, “so we went down to Mexico.”

Used to go down there, to get my hair cut a lot. That's when I started to develop the opinion there was something Christ-like about beggars. You'd see a guy with no legs on a skateboard, mud streets, church bells going. If you went to a restaurant my Dad would invite the mariachis to the table and give them two dollars for a song. Then he would wind up leaving with them and you would have to find your own way back to the hotel. Dad would come home a day later because he fell asleep on a hilltop somewhere looking down on the town.

When Waits was 10, his father walked out and didn't come back. "The family kind of hit the wall and cracked up and it went by the wayside. But I do remember the music." Hoskyns emphasizes the point:

In the song “Frank's Wild Years” (from Swordfishtrombones, 1983) Waits used his father's name to tell the tale of a furniture salesman who — having "hung his wild years on a nail that he drove through his wife's forehead" — bought a gallon of gas and torched his suburban home. Metaphorically at least Frank Waits did exactly that.

The young Waits became fixated with fathers. “When he visited his friend's houses, he often stayed indoors talking to their dads about “real man stuff” like lawn mowing and life insurance,” Hoskyns writes. “Plus he liked checking out their Frank Sinatra albums." By the age of twelve, Waits was wearing a trilby and carrying around his grandfather's walking stick. Early on Waits realized he was going to have to be his own father. As he told Tim Adams of The Observer last year:

There was a need for maturity and guidance from somewhere and I was going to have to provide it for myself — even if it meant putting on an overcoat and a hat and looking in a mirror and squinting a bit.

On Closing Time, Waits’s 1973 debut album, this odd, wizened-yet-young trait stands out. Take, for example, the track “Martha,” in which Waits, all of 23, inhabits the character of "old Tom Frost” and addresses a girl whom he'd loved 40 years before, remembering "quiet evenings, trembling close to" her.

Much of the rest of the album is of its time. Waits comes across as not entirely dissimilar to Jackson Browne or even Billy Joel. He had signed with David Geffen's Asylum label, which, as Barney Hoskyns points out “was all about marketing the incestuous community of the Los Angeles canyons.” That isn’t what Waits wanted, as he told Jeff Walker for Music World in 1973:

I'm getting pretty sick of the country music thing. Much of it is really Los Angeles country music, which isn't just country, it's Laurel Canyon. It's very difficult to live a country frame of mind when you're living in LA, so I just identify more with the sounds of the city.

In “Ol' 55,” the album's best track, Waits does locate his typical, melancholy lyricism in the banality of urban American life. An easy listening On The Road, the song is a hymn to a beat-up old Buick. The young lover leaves his girlfriend's bed to drive home at six in the morning, feeling “so holy” and “alive” as the sun comes up — the chorus a simple, un-ironic chant of "Freeway cars and trucks."

The title track for Waits’s second album (Looking for) The Heart of Saturday Night confirms his ambition to be true to his vision of himself as a jazz-centric Beat poet. The idea comes straight from Kerouac's Visions of Cody, in which the protagonist was "hurrying for the big traffic, ever more exciting, all of it pouring into town Saturday night." Composing the song while literally cruising down Alvarado Street and Hollywood Boulevard, Waits was striving after an elusive epiphany, trying to locate stillness in motion or find a center of innocence in America's most heartless city. Influenced by Charles Bukowski (Waits had discovered him in the splendidly named “Notes of a Dirty Old Man,” a weekly column in the Los Angeles Free Press) the lyrics have a tight honesty in the clarity of detail "Tell me is the crack of the pool balls, neon buzzing / Telephone’s ringing; it's your second cousin." Even the traffic sounds effects have a local authenticity, Waits having wandered out onto Cahuenga Boulevard, tape-recorder in hand.

In addition to sharing the Beat aspiration to be a "writer of the common people and street people,” as he described Bukowski, “looking in the dark corners where no-one seems to want to go," Waits was also pushing his music towards more of a jazz-blues aesthetic, influenced by the album Poetry for the Beat Generation (1959) that Kerouac had recorded, on which he spoke his “beat prosody” over jazz chords. Geffen decided to bring in the smooth music industry producer Dayton 'Bones' Howe, engineer of albums as diverse as Ornette Coleman's The Shape of Jazz to Come (1959) and Frank Sinatra's Swing Along With Me (1961). The fact that Howe had edited an album of Kerouac recordings endeared him to Waits. It was an unlikely pairing, but, given his 16 years seniority, Howe became the first in a series of influential father figures that Waits sought out.

Howe put together a veteran ensemble of jazz and pop musicians, including pianist Mike Melvoin, who had been featured on the Beach Boys' Pet Sounds. The seasoned Los Angeles session musicians, like bassist Jim Hughart found the 23-year-old singer odd, "with his Salvation Army clothes and scruffy beard and kind of a beat-up hat and talking in a voice you could barely understand." Melvoin himself saw Waits’s persona as "round the clock performance art": “I thought of Tom as a professional poet who was in character.” The group gelled and created a sound both looser (such as “Diamonds on My Windshield” where Waits drives at night in the rain and is overtaken by a Plymouth Duster as he travels the I-5 from San Diego to Los Angeles) and far more layered (“Fumblin with the Blues"). It was a sound that would, with development and modulations, last several more albums.

A close look at the cover painting of The Heart of Saturday Night reveals Waits’s strange mixture of the bashful yet knowing outsider. A femme fatale approaches him along a sidewalk soaked in neon, which shouts Los Angeles noir. But is Waits involved, a paying customer or merely an amused observer? He fiddles with his ear and stares downwards. The photograph on Nighthawks at the Diner, the live album Waits recorded shortly afterwards, also has a teasing ambiguity. In place of Edward Hopper's iconic, stylized, noir tableau, Waits is photographed with a messy realism, but, with a studied pose, frozen like a mannequin in a shop window, he returns our gaze and undoes any sense of naturalism. The album is also a curious hybrid, a live performance in a studio dressed up to resemble a nightclub. As a surreal, finishing touch, Herb Cohen, Waits’s manager, had the show opening with a stripper twirling her tassels while the band played the theme from The Pink Panther and “Night Train.” Yet, when Waits name checks such favored local establishments as Norm's on La Cienega in “Eggs and Sausage (in a Cadillac with Susan Michelson),” he gives us a palpable sense of the real verging on the parochial. “Emotional Weather Report” goes further, with Waits using Los Angeles as an extended meteorological metaphor, warning of "gusty winds [...] around the corner of Sunset and Alvarado" and "the ticket-taker's cold smile at the Ivar theatre."

But, by the time he records Small Change (1976), Waits is already encountering problems with his real and stage identity. "All of a sudden it becomes your image and it's hard to tell where the image stops and you begin or where you stop and the image begins," he told the Los Angeles Times in March 1976. He was boozing heavily while, at the same time, writing amusing apologias for drunks in songs such as "The Piano has been Drinking (Not Me)." Alcohol had become his subject and his muse. Waits’s finest song, "Tom Traubert's Blues," emerges from this compulsive need to bear witness, to share the life of the drunk. Engineer and producer Bones Howe told Hoskyns that Waits felt he needed to spend time in Los Angeles's skid row:

He said, "Everyone of those guys has a story." And later he called me up and said, "I took the bus down there, found a liquor store, bought a pint of rye in a brown paper bag, squatted down in the street and talked to everybody that came by. And then I went home, threw up and wrote ‘Tom Traubert's Blues.’”

Waits gives his own name to the song's protagonist. The guy he begs a couple of bucks from, of course, is called Frank. It's at this point that Waits’s voice starts to change and become an instrument in its own right. He finds a deeper, ravaged, rasping sound, appropriate for a place where "no-one speaks English and everything's broken."

Given Waits’s alcoholic romanticism, the influence of hardboiled noir fiction in Small Change, with its dual notes of cynicism and sentimentality, blends in perfectly. “The One that Got Away” and “Invitation to the Blues” seem lifted straight from the pages of Chandler and Hammett. The album cover places Waits, like a sleazy private investigator, in a bored stripper's dressing room, dildos and the detritus of makeup scattered beside him. Like Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver (also released in 1976), it's an image of an alienated male, adrift in a sea of vice, partly perceived through the gauze of 1940s fiction. In his next album, Foreign Affairs, Waits addresses his growing film noir obsession head on, basing songs such as “Potter's Field” on Sam Fuller's Pickup on South Street and “Burma Shave” on Nicholas Ray's They Drive By Night.

Despite such self-conscious use of fictional genre and character, Waits was increasingly blurring the line between the real and the imagined in his own life. By the late 1970s drugs and dealers had overrun the Troubadour and he was living next door to pimps in the Tropicana: "I found myself in some places I can't believe I made it out of alive. People with guns. People with gunshot wounds. People with heavy drug problems […] You live like that, you attract lower company." Even Duke's, the cherished coffee shop, had become the scene for Waits and Weiss's violent, wrongful arrest for disturbing the peace.

They threw us into the back of a pick-up with guns to our temples. Guy says, "Do you know what one of these things does to your head when you fire it at close range?" He said “Your head will explode like a cantaloupe."

The arrival of a femme fatale in the shape of Rickie Lee Jones only added to the romantic confusion of life and art. The first time Waits saw Rickie Lee she reminded him of Jayne Mansfield, he told Hoskyns. "I thought she was extremely attractive [...] My first reactions were rather primitive, primeval even." Staggering down their West Hollywood neighborhood in search of drink and drugs, Waits, Jones and Weiss quickly formed a Gang of Three, echoing the similar self-mythologizing ménage à trois between Kerouac, Neal and Carolyn Cassady. Hoskyns quotes Jones saying they were like "real romantic dreamers who got stuck in the wrong time zone."

The album Blue Valentine is packed with references to Waits and Jones's jazz-life affair and the currents of Los Angeles violence swirling around them at the time; "Red Shoes by the Drugstore" alludes to a wild Christmas, with Rickie Lee as "the little blue jay/in a red dress”; “$29.00” is a conversation overheard when Waits's pimp neighbor was being harangued by one of his whores; "Sweet Little Bullet from a Pretty Blue Gun" is based on the suicide of a 15-year-old girl who had jumped out of a 17th floor window on Hollywood Boulevard; “Romeo is Bleeding” is a retelling of a Mexican gang-slaying in an East Los Angeles movie house. Waits even chooses to cover Bernstein and Sondheim's “Somewhere,” a favorite of Jones’s.

The music was now darker and harder, with Waits shifting his influences towards the guitar-based New Orleans R&B. "Whistlin’ Past the Graveyard” demonstrates how far Waits had traveled lyrically and tonally. "I know you seen my headlights/ And the honking of my horn/I'm calling out my bloodhounds/ Chase the devil through the corn/Last night I chugged the Mississippi/Now that sucker's dry as a bone/Born in a taxi cab/I'm never coming home."

“Christmas Card from a Hooker in Minneapolis" shows that his ability to inhabit unreliable narrators and to create twisted, false personas was also deepening. This overt theatricality spilled into his live performances while promoting the album. Always conscious of the need to stage his act, Waits had an entire gas-station set built, with a Super 76 gasoline pump somewhere between Edward Hopper's “Gas” and Ed Ruscha's “Standard Station.” Waits’s concerts were beginning to resemble mini Broadway shows, anticipating his work on “One From the Heart” and “Frank's Wild Years.” Like that other identity-shifter, Bowie, Waits’s protean ability would allow him to move into movies in the 1980s (although his first role was a predictable, low-life drunken pianist in “Paradise Alley”). In turn, movies would offer him further ways to move beyond what Hoskyns calls the "faux/jazzbo shtick" that he had found constricting.

Rickie Lee Jones's overnight international success with “Chuck E's in Love” had lead to a downward spiral of heroin and cocaine abuse as she struggled with the usual effects of fame. Weiss too was turning into a junkie. Waits’s response lies in his ravaged, wounded voice and the harsh electric blues that define "Heart Attack and Vine.” When he and Jones split up, he moved out of the Tropicana and into a more laidback East Hollywood neighborhood, close to his father. By day he worked in the old RCA building on Sunset and Ivar, pushing his images and verbal fragments into a new kind of coherence. Gone was Chandler's white knight in the form of Marlowe, or the melancholy search for the urban epiphany. In its place is the voice of a semi-psychotic street predator, snarling over savage guitar and bass. "The title track was a breakthrough for me,” Hoskyns quotes Waits saying. “Using that kind of Yardbirds fuzz guitar, having the drummer use sticks instead of brushes and small things like that. More or less putting on a different costume." While “Heart Attack and Vine” is his finest Los Angeles song (Waits had witnessed a woman stumble into a bar off Sunset, collapse on the floor with a heart attack only for the bartender to look at the crying woman and tell her to take it outside), it also points away from the city and foreshadows the radical personal and musical break he was about to make.

Waits had met Kathleen Brennan while he was composing the soundtrack to One From The Heart. She was working as a script editor on the movie. They were engaged within a week. Coming from a large Irish American family, Brennan was emotionally balanced and stable, decidedly not the Rickie Lee type. "I'm alive because of her,” Waits told Mick Brown in 2006. “I was a mess. I was addicted. I wouldn't have made it. I really was saved at the last minute, like deus ex machina." Even allowing for Waits’s customary self-dramatic exaggeration, there's no doubt about the level of change that Brennan effected. Soon they would leave Los Angeles and start a family life of rustic seclusion in Northern California. Many of his old friends and musical collaborators would be jettisoned as Waits embarked on a new cycle of reinvention. He would leave both his manager and record label, Asylum, after a decade, to protect his musical freedom. And Brennan herself would become the producer and co-writer of the new Waits.

The turning point, the key that unlocks the door, as David Smay points out in his fine analysis of the album, is Swordfishtrombones, Waits’s first collaboration with his wife. Although it was recorded in Hollywood, it's most definitely not another Los Angeles album. It feels like world music, both in the range of its harmonic variations and in its geographical references (Australia, Hong Kong, New York, Fellini's Rome). According to Hoskyns, "Brennan was the person to expose Waits to the sounds that lay outside the commercial pop-rock spectrum.” As Waits put it a Newsweek interview in 1999:

She was the one that started playing bizarre music. She said, "You can take this and this and put all this together. There's a place where all these things overlap. Field recordings and Caruso and tribal music and Lithuanian language records and Leadbelly. You can put that in a pot."

The Swordfishtrombones tracks have a loose narrative coherence. It may not be a full libretto but it's a story of sorts, a guy who joins the merchant marines, “gets in a little trouble in Hong Kong,” comes back, gets in trouble at home, leaves again. What Swordfishtrombones establishes, beyond all doubt, is Waits’s exceptional ability to create original, layered sound textures, harsh and varied enough to embody his more allusive, darker lyrics. The opening track "Underground' is like a statement of intent, a subterranean manifesto declaring the extent of his artistic ambition. Ostensibly a march of mutant dwarves, the song hammers you into submission with brutal percussion, flatulent trombone and exotic marimba clonks. Waits had assembled a brilliant and eclectic collection of musicians; Victor Feldman on a range of percussive instruments, Francis Thum (who had introduced Waits to the work of musical pioneer Harry Partch) on metal aulongs, Larry Taylor on bass, Fred Tackett on guitar and banjo and Steve Hodges on pounding drums.

“Shore Leave,” about a bedraggled sailor "in bad need of a shave," pining for a girl back in Illinois, might seem like a typical Waits blues, but the song is given such an expressionistic melee of sounds it takes us into another world, the aural equivalent of a waking nightmare. Waits had found his own way through to the dialectical freedom of Brecht and Weill, his personal version of musical theatre, where sound and lyric combine to define a character's sense of their world. It's a freedom from which he has never looked back.

The deliberately parochial “In the Neighborhood” feels like a final farewell to Los Angeles, in which he both complains about and celebrates his Silver Lake backyard. In the music video (filmed by the great cinematographer Haskell Wexler), Waits prances down an alley near his house with an assembled circus of dwarves and hulks. Underscoring its Fellini-esque qualities, Waits chose legendary strongman Lee Kolima and midget Angelo Rossitto (who appeared in Tod Browning's 1932 cult film Freaks) to share the album’s cover photo. “In The Neighborhood,” Waits’s last postcard to and from Los Angeles, his final walk around the block, remains rooted in the familiar and the domestic, even if it's falling apart. "There's a couple of Filipino girls/ Giggling by the church/ And the window is busted/ And the landlord ain't home/ And Butch joined the army/ Yea, that's where he's been/ And the jackhammer's digging up the sidewalks again./ In the neighborhood. In the neighborhood.”

Both Lee Kolima and Angelo Rossitto are long dead. Silver Lake is now gentrified. The back street where the video was filmed is an unremarkable and uneven piece of tarmac. The site of the dyspeptic Tropicana Motor hotel is now occupied by another anonymous Ramada Inn. The Troubadour and the Ivar Theatre are standing but the life has gone from them.

But, as Waits pointed out in a recent interview with Tim Adams in The Guardian, that music provides a kind of time travel.

The studio is torn down, all the people who played on it are dead, the instruments have been sold off. But you are listening to a moment that happened in time 60 years ago and you are hearing it just as sharp as when it was made.

As Hoskyns shows, Waits the man, like many of his personae, is an unreliable narrator. His attitude to autobiography was summed up in the lines from “Tango Till They’re Sore”: "I'll tell you all my secrets, but I lie about my past."

LARB Contributor

Alex Harvey is a writer and director based in Los Angeles. His book Song Noir: Tom Waits and the Spirit of Los Angeles was recently published by Reaktion Books in the United Kingdom and University of Chicago Press in the United States. He is currently making a film about Satyajit Ray and Kolkata.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

¤

¤