How to Forget a Massacre: What Happened in Paris on October 17, 1961

Laurel Berger revisits the events of October 17, 1961.

By Laurel BergerOctober 17, 2019

I.

THE FIRST TIME I heard about the episode, on a French news program, I found it hard to credit. In 1961, Parisian police chucked an untold number of Algerian migrants into the Seine and left them to drown. Decades later, the massacre still has no name; it is known simply as October 17 and it exemplifies the Republic’s failure to reckon with its colonial history. When I asked ordinary people about this once-suppressed atrocity, I discovered that I was not alone in my ignorance.

A witness named Rahim Rezigat wants to mend that broken connection to the past. For the last few years, he’s been conducting memory “walks” through Paris neighborhoods and suburbs, to places that illuminate aspects of France and Algeria’s intertwined histories. In Saint-Denis, a Paris suburb with a large Muslim population, the memory tourists visit the Basilica of Saint-Denis, a mosque, a monument to mark the abolition of colonial slavery, a four-year-old patch of lawn near the railway station that carries the name of the anti-colonialist thinker Frantz Fanon, and La Place des Victimes du 17-Octobre-1961.

Rezigat, who was born in Algeria and came to France at the age of eight, runs what might be described as a postcolonial travel society from an office in Saint-Denis. (Motto: “I appreciate my neighbors better when I take an interest in their culture.”) When I joined him on a bright morning in May 2017, the walk was hobbled by delays. To document the expedition, Rezigat had hired a videographer. The opening sequence was meant to have gone like this: head of tourist bureau exchanges civilities with Monsieur Rezigat and bids memory tourists a pleasant journey into the past. Unfortunately, the official in question could not keep the appointment. (A subordinate delivered news of his cancellation.) The mayor of Saint-Denis was busy, too. The local poet who was scheduled to join the walkers for “a friendly glass” sent her regrets. The ethnically diverse video people had words with the ethnically diverse neighbors whose town they, the video people, were determined to show to best advantage. And then there was the problem of those memory tourists. There weren’t any. If Rezigat was demoralized by the course of events, he did not show it. He’s an unassuming man, with a fluff of white hair and a rumpled face, who has seen a lot.

At the heart of the project was a perennial question: how should a country remember the dark history it would rather forget? Not just the cataclysms and catastrophic events, the singularities, but the state-sanctioned systems that arguably predate and enable episodes of mass violence, systems about which we know far less. In today’s populist Europe, where constitutions have been amended to accommodate historical denialism, the question is all the more pertinent.

By chance, two weeks before Rezigat’s memory walk, then-presidential candidate Emmanuel Macron had reflected on the French situation with journalists from the news site Mediapart. Alluding to the fund of enduring grievances over the 1954–’62 Algerian War of Independence — which, in his words, was “paralyzing France” — he promised, if elected, to initiate a national conversation about the colonial past and take “powerful action.” (Previously in his campaign, he’d suggested that French rule in Algeria was a crime against humanity. The remark cost him, and before long he apologized.)

By most estimates, it is both too soon to talk about French rule in Algeria and rather too late. Too soon, in part, because feelings about the war are still raw; too late because contemporary accretions, like the Paris terrorist attacks of 2015, the influx of Muslim refugees, and the threat of French jihadism cloud the retrospective view. Most contentious of all, however, are the contradictory, polarizing memories of the roughly 10 percent of the French population who have a connection to Algeria whether through family ties or the War of Independence. The historian Robert Paxton once wrote of how the Vichy quarrel was “transmitted to new generations by becoming grafted upon historic quarrels — between right and left, Catholics and anti-clericals, defenders of the Rights of Man and anti-Semites.” [1] The same could be said of the Algeria quarrel, which endures.

Macron was undaunted. A year ago, he invoked the specter of empire anew. For the first time in France’s history, the president of the Republic acknowledged what was no secret: throughout the conflict with Algeria, the French army systematically tortured antiwar activists, including people whose only crime was to sympathize with the Algerian cause. A young activist named Maurice Audin had been tortured to death. Torture, Macron said, was facilitated through a system of arrest and detention that was approved by Parliament in 1956 (as part of the Special Powers Act) and “implemented by prefectural order, first in Algiers, then throughout Algeria in 1957.” Those orders militarized the police and granted policing powers to the military. Macron’s assertion made it sound as though the human rights abuses were limited to the other side of the Mediterranean. In fact, state terror was deployed in the French capitol from 1957 until the end of the war in 1962; during those years, Parisian police and security forces randomly detained, tortured, and executed Algerians and those who looked Algerian.

You don’t have to read far into the historical or investigative literature — from the early work of the journalist Jean-Luc Einaudi to later research by the historian Emmanuel Blanchard, who showed that Algerians in Paris were maltreated by police for decades — to grasp that the reticence surrounding the events of October 17 is of a piece with the greater silence around Algerian decolonization. Historians rightly stress that the campaign of state violence against Muslims in Paris can only be understood within the broader context of the period. This was a time when the Fifth Republic was under attack from all sides. Yet while the complex forces that allowed the police and military to act with impunity were forged in the crucible of that war, they were underpinned by power structures and social attitudes that have shaped political culture in France ever since.

Around the time of the 2017 French presidential election, while in Paris, I caught echoes of the old colonial rhetoric in the stump speeches of the far-right candidate Marine Le Pen and also in the tide of anti-immigrant feeling that had bloomed in the West. Back home, reactionaries in the American South were affirming their right to display the Confederate flag. The United States was separating families at the US-Mexico border. Police officers were still shooting unarmed people of color. Increasingly, the events of Paris 1961 seemed worth revisiting.

I was given Rezigat’s telephone number by a historian who’d heard him talk about how he’d escaped arrest on October 17, 1961. And so, in the immediate aftermath of Macron’s electoral victory (which felt less like a triumph than a close call), I rang him up and he invited me to accompany him on his inaugural crawl through Saint-Denis. Shortly before we set forth, he struck up a conversation with the bad-news-delivering official at the tourist office. She was in her 30s, a daughter of Algerians who had raised her in the shadow of the October 1961 massacre. Even so, she said, there were things she didn’t know about the episode. Rezigat gave her the short version. In a different setting, with a bit more time, here is what he might have told her:

In October 1961, the Paris prefect of police, Maurice Papon, effectively put every Algerian Muslim in the city under house arrest. Papon was a proficient colonial administrator and former Nazi collaborator who dispatched almost 1,600 Jews from Bordeaux to German death camps during the Occupation. [2] (In 1998, he would be convicted of complicity in crimes against humanity by a French court.)

Empowered by Charles de Gaulle’s administration and urged to wipe out the Algerian nationalist movement in Paris, Papon took it upon himself to issue a series of anti-Muslim edicts. Algerian Muslims were told to move about alone lest they be detained on suspicion of terrorism. They were “most urgently advised” to keep off the streets at night. If they drove a car, they could be randomly stopped, arrested, and their autos impounded “at any time.” Though the injunctions had no legal standing, members of the security forces, with rare exception, treated Papon’s word as law.

They did not require much encouragement. That summer, the French Federation of Algeria’s National Liberation Front, or FLN, assassinated 22 Paris police officers and harkis — indigenous Algerian soldiers who’d thrown in their lot with the French. FLN commando attacks on the mainland began in the 1950s but by the summer of 1961, these assassinations were largely a response to the stranglehold that French forces held on the Algerian community in Paris. British researchers Jim House and Neil MacMaster make that argument in their book, Paris 1961: Algerians, State Terror, and Memory; they quote a telling exchange between the novelist Marguerite Duras and an Algerian worker. Asked by Duras to sum up his life in one word, the man replied, “I think I can give an exact answer: terrorized. We lead a terrorized life.”

All that autumn, security forces and paramilitary death squads shot, clubbed, rifle-butted, bludgeoned, and strangled with brake cables people with brown skin. Corpses were cut down from trees in the Bois de Vincennes.

Then came the October imposition of an “Algerian” curfew amid other humiliations. The timing was deliberate. With the French and the Algerians in peace talks, an unofficial ceasefire was in effect, which House and MacMaster contend Papon exploited to rachet up the pressure on the nationalists. In reprisal, and also to show that the people were behind them, the FLN French Federation determined to stage four consecutive days of nonviolent strikes and marches on Paris. Rezigat, then 21, was among the 20,000 Algerian men, women, and children who took to the streets on the evening of October 17, 1961. An FLN militant at the time, he had spent the previous three years in some of mainland France’s harshest internment camps. Upon his release, he found a job on an assembly line at a lightbulb factory and a bed at a workers’ dormitory in the southwestern suburbs.

That day, when his shift ended, he returned to his hostel, put on his best button-down shirt and jacket, and set out for the center of the city with a friend. The geography of the demonstrations was impossibly complex. People were coming from all directions and were meant to converge in columns at central points throughout the city, but in many cases, the police cut the marchers off at the pass. Word spread and once Razigat reached the Porte de Versailles, demonstrators warned him that the security forces were hunting down Algerians. In fact, Papon’s forces were capturing and bashing in the skulls of Algerian protestors throughout Paris, from the outlying suburbs to the Place de l’Opéra to the Champs-Élysées. At the Pont Saint-Michel and elsewhere, observers witnessed policemen throwing people from the stone parapets of bridges into the Seine. The current would bear away the dead, dying, and the unconscious.

Rezigat and his friend escaped the police sweeps by hiding out in a park near the hostel until the end of curfew at daybreak. That night, more than 12,000 Algerians were rounded up and jailed in makeshift detention centers. Some were shot to death in the toilets. Others were beaten and tortured by their jailors, then patched together by medics only to be brutalized again.

About a week later, the police came to Rezigat’s boardinghouse. They hauled him and the other occupants to the Vincennes Detention Center, where they were received by a company of officers who delivered kicks and blows. They weren’t too hard on Rezigat, which he attributes to his small stature and the fact that he looked like a kid. The following day, at 10:00 in the morning, they let him go, but 40 men who were arrested with him never returned.

Even if all the national and police archives were opened up tomorrow, we still wouldn’t know how many people were slaughtered in the October ’61 atrocity. Reliable estimates range from “dozens” over the October 17 and the days following to more than 200 over a longer period. What is beyond dispute is that for months, both before and after the demonstrations, Papon had required the men under his command to meet arbitrary arrest, internment, and deportation quotas, which House and MacMaster contend were “organized at the highest levels of the French state.”

The cover-up began at once. Papon recast the atrocity as a battle between Algerian terrorists and the police, a narrative that reinforced the idea of the Muslim “Other” in the popular imagination. In his telling, the Algerians had fired on the officers from within the crowd. He declared victory over the rebels and reported just two Algerian protestors dead, killed by the police in self-defense. In truth, the demonstrators were unarmed and the security forces had long lethal clubs and weighted capes and submachine guns. Weeks before, on October 2, 1961, at the funeral of a policeman assassinated by the FLN, Papon had announced: “For every blow received, we will render ten.”

Critical articles in Le Monde and France-Observateur (whose editor, Claude Bourdet, confronted Maurice Papon and the interior minister with eyewitness accounts of police beating a pregnant woman) made slight impression on war-stunned Parisians. “Happy are the blonde Kabyles!” an esteemed député exclaimed before the French National Assembly. [3] Both the right-wing prime minister and the interior minister were opposed to Algerian independence and they backed Papon in the matter, declining to open a probe. Official denials were issued, photographs were suppressed, and information was withheld. Journalists were kept at a distance from the detainees, save for an invitation to Orly Airport to witness the hospitable manner in which they were returned to Algeria. Parisian press reports told of dangerous reprobates sent “home” to French camps, aboard comfortable Air France jetliners. In their book, House and MacMaster recount how the men who had subsisted on dried dates and crusts of bread during their confinement enjoyed an in-flight lunch of assorted hors d’oeuvres and cold beef. [4]

II.

During our walk, Rezigat paused before the stone facade of an elementary school, not far from the Basilica of Saint-Denis. It wasn’t much to look at — a plaque of gray marble in memory of the Jewish students who’d been deported to German concentration camps under Vichy with help from French police. Such plaques were all over the city, even in front of nursery schools. But that was half of his point. In the nation’s capital, there are relatively few plaques and monuments to mark the sites of state violence against Algerians. And that is because the Algerian conflict was an internal affair, and therefore, best forgotten. For unlike Vichy, which the French viewed as imposed on them by the Germans, Algeria was France. The Algeria problem, which was none other than the problem of Empire, put an end to the Fourth Republic, brought the country to the brink of civil war, and led Resistance heroes and public men and decorated officers to engage in or countenance acts that clashed with the myth of humanist France.

The state dealt with the complexities of that legacy through elisions and silence, excising dark truths about the colonial past through the censorship of school textbooks, films, and literature. When Rezigat was about the age of the school children who were now capering about, waving to the video camera — he learned in class about “his” ancestors the Gauls. During his secondary education, the history of Algeria before the French conquest of 1830 was barely covered.

To be sure, former colonial powers aren't alone in their mythmaking. Dictators, nationalist movements, revolutionary governments, and democratically elected parties all rewrite history to consolidate their power. In postcolonial Algeria, the schism between Islamic and socialist-modernist camps of the FLN resulted in the erasure of centuries of non-Arab culture. And the Algerian government has also kept alive its own distorted version of October 17. After a period of silence, the shape-shifting nebula that has ruled the country since independence fashioned a heroic narrative that is retold each year on National Immigration Day. (Although Algerians were French citizens before 1962, they were for all intents and purposes regarded as migrants, a perception that neither country cares to correct for different reasons.) “On that glorious date,” a press release issued by the Algerian Ministry of Foreign Affairs explains, Algerian immigrants in Paris, political actors “in one of the most glorious chapters of Algeria’s resistance against colonial rule” proved their “enduring attachment to the motherland.”

Refracted through that bad light, the French omissions are all the more jarring. In 2005, the government signed into law a bill requiring school teachers to underscore “the positive role of the French presence overseas, notably in north Africa.” After intellectuals issued a statement in protest, the law was repealed the following year. Even so, many of France’s former colonial subjects took its passage as just one more attempt by the Republic to conceal the brutalities of the imperial system.

III.

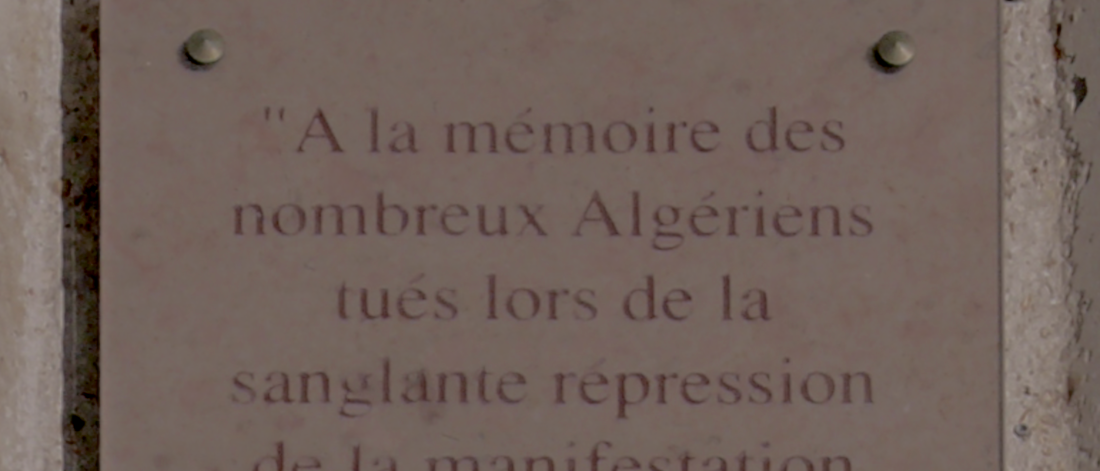

The bronze tablet beside the Pont Saint-Michel is hard to find. Upon its surface is inscribed:

In memory of the Algerian protestors killed during the bloody repression of the peaceful demonstration of October 17, 1961.

The letters have the gouged-out look of cuneiform on clay. The phrase was arrived at after protracted debate in Paris City Council chambers in 2001, but the language is still impenetrable. On any given day, passers-by can be observed trying to decode the meaning of those words, which one activist described with a sigh as “a total euphemism.” (By way of comparison, consider the other inscription to the massacre, next to the bridge leading to the Place des Victimes du 17-Octobre-1961: “Some protestors were shot to death, hundreds of men and women were dropped into the Seine, and thousands more were beaten and jailed.”)

Linguistic clarity around these issues and events is a consistent problem in France. In 2012, then-president François Hollande officially and euphemistically recognized “with lucidity the bloody repression of Algerians” on October 17, 1961. Mild though it was, even that small gesture drew ire from politicians on the extreme right and from certain quarters on the left. “This must be his third repentance in five months,” Marine Le Pen sniped on a French talk show. Raising questions about how history shapes national identity, she contended that Hollande’s acknowledgment of “eminently contested events” would have a parlous effect on “certain French youths who view France with a hostility that borders on hatred and feel that France is in their debt.” [5] Her party, the far-right Front National (which now calls itself Rassemblement National) promotes a populist version of national identity that glorifies the country’s white Christian heritage and history. In the past, she has contested the established facts of October 17, 1961, dismissing them as “nonsense.”

While Le Pen and her followers represent one extreme, another part of society views the Algerian War as a historical irrelevance. “The trouble is that many French people aren’t aware of the full extent of the acts committed in their name,” said Olivier Le Cour Grandmaison, a lecturer in political science and a member of the United Collective for the recognition of state crimes in Algeria. By way of reparations, its members want the Republic to erect a national monument to all the Algerian victims of French colonial violence and offer a comprehensive apology for state violence in Algeria and in metropolitan France.

“It’s striking how every 10 years or so we French rediscover that we tortured Algerians during the war and a state massacre was committed on October 17, 1961, in Paris,” Alain Gresh, the former longtime editor of Le Monde diplomatique remarked at a café one morning. “Everyone knew about October ’61, and then it was forgotten. What does our refusal to fully accept this episode say about our relationship to the people who carry its memory?” Sartre, writing in Les temps modernes, denounced the act as a pogrom; Simone de Beauvoir noted that her then-lover, the filmmaker Claude Lanzmann, had seen “teeth smashed in and skulls fractured with his own eyes.” [6] And yet, as Gresh observed, for all the heaps of academic papers and scholarly works and popular accounts that have been written about the episode, October 17 barely registers in the collective psyche.

The survivors, for the most part, kept quiet until the advent of activist groups in the ’90s. Even then, relatively few came forward. The youngest escapees commonly repressed the memory of that night, only to experience flashbacks as adults. This was true of Khaled Benaïssa, who told me his story at a brasserie on the Place de Clichy. Although the restaurant was empty, he spoke in a murmur “so as not to disturb anybody.” In 1961, he was a frail child of 12. On the evening of October 17, he, his father, and an uncle left their home in Nanterre and boarded a Paris-bound bus that was packed with their fellow Algerians, all under FLN orders. While some on the French left have alleged that the group blithely sent Algerians to the slaughter, those views are at odds with historical consensus. According to Jim House, there’s no evidence that “those behind the demonstration necessarily expected a massacre, but, rather, wide-scale beatings and a large amount of arrests.” Blanchard concurred, saying that the French Federation leadership was prepared for a repression, yes, but not a bloodbath.

Having never been to Paris before, the boy Khaled was very excited. Just before the Pont de Neuilly, where thousands of marchers had been brought to a halt by riot police and soldiers, the driver slammed on his air brakes, opened the doors, and ordered everyone out, into the tide of demonstrators. At the sight of men with machine guns on the bridge, Khaled tightened his grip on his uncle’s hand. Once the shooting began, the two were wrenched apart. He tried to fight his way out of the crowd, and in his panic, he lost his footing. Caught in the great human undertow, Khaled found himself upside down: his small legs upraised, head near the ground. He could barely breathe. All this Benaïssa recounted without emotion, except for this one moment, when he believed that he was going to die among strangers, from suffocation. The table began to shake and the coffee cup he held in his hands rattled in its saucer.

I remembered that cup and those shaking hands when I spoke to Benjamin Stora, the preeminent historian of colonial Algeria at his basement office in the Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration, where he works. Asked if he thought France might ever establish a South Africa–style Truth and Reconciliation Commission to deal with the wartime atrocities committed by both sides, he furrowed his brows. Citing amnesty laws passed by the de Gaulle administration in 1962 and 1968, he went on to say that it was unlikely, adding, “Unless all parties told the truth, no genuine reconciliation would come of it.”

Certainly, he knows what an elusive concept “truth” can be. In books like The Transfer of Memory: From “French Algeria” to Anti-Arab Racism, Stora, who was born into a Jewish family of merchants in the Algerian city of Constantine, argues that during decolonization a great jumble of memories and traumas were transferred from one generation to the next. When Algeria achieved independence, approximately 600,000 settlers and indigenous Jews removed to France, losing the only home many had ever known. On the other side were the Algerians who’d fashioned makeshift lives for themselves in Paris. For that contingent, the abuses they suffered at the hands of the French were compounded by sectarian violence after decolonization. Riven by factionalism, FLN cadres slaughtered rival insurgents and their rank-and-file sympathizers.

After independence, the schism between the Islamist and socialist-modern factions within the FLN deepened. In 1992, the military suspended legislative elections after an Islamist victory seemed assured. The power grab saved Algeria from becoming a fundamentalist Muslim republic; it also resulted in a decade of murder and mayhem that left 150,000 Algerians dead. And when the country at last achieved a fragile peace, it, too — as France had done decades earlier — retreated into silence and forgetting. Such were the aftershocks and ambiguities of the Algerian revolution.

“Do you tell your children that Algerians were killed by Algerians?” Stora asked, referring to the silence of the Algerians who stayed in France after the signing of the Évian Accords in 1962. “By the end of the War of Independence and well into the 1980s, those immigrants had the opportunity and the desire to assimilate into French society. But to achieve that, they couldn’t be in a state of perpetual rumination. And if they were to remain in France, there were things they could not say. So between ‘family secrets’ and state censorship, what you’re left with is a great big memory hole, an amnesia that lasted four decades.”

But people don’t forget the nightmares of lived history, only states do, or they try to, anyway. A case in point: it took 55 years after the end of World War II before the French Republic put Maurice Papon on trial for the crimes he committed under Vichy. To demonstrate that Papon wasn’t an innocent actor, the prosecutor allowed historians, eyewitnesses, and survivors to testify about October 17, thereby drawing international attention to the atrocity. It was a canny move, because the focus on Papon served to direct attention away from the responsibility of the Gaullist administration. To further distance itself from the episode, the government commissioned a report, a perfunctory document whose authors concluded only that the police, on Papon’s orders, had used excessive force in repressing the demonstrations.

Now, as France approaches the 58th anniversary of the October 17 massacre, how will it remember the atrocities carried out in both Algeria and on the streets of Paris during the War of Independence? Referring to the strand of public opinion that still maintains that the French effectively brought civilization to Algeria, Samuel Everett, a Franco-British political anthropologist in Paris, said that he and others are pushing for open discussion about French colonial rule and for its legacy to be dealt with as an open wound. “Particularly in a country as historically aware as France, anyone who's been through the system and who has other histories, too, will have thought about the extent to which those other histories are not acknowledged.”

Unequivocally worded markers might help heal these wounds. Some of that work is already being done at the Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration, and through grassroots efforts like Rezigat’s. Activists have also made local progress, most notably at La Place de la Nation, where a plaque now commemorates the seven Algerians killed and 50 wounded by police during a demonstration on July 14, 1953. Macron’s apology to Maurice Audin’s widow, Josette, and his promise to open the archives was a start, but what’s also needed are new stories about the era and ways of imagining the past that might illuminate the present. “The French colonial legacy functions as a litmus test,” Olivier Le Cour Grandmaison said. “Because to suggest there’s a connection between our inglorious past and the treatment of French citizens of North African descent in les quartiers populaires today is seen not only as a political act but a provocation.”

France’s colonial past is not solely responsible for its contemporary social and ethnic tensions, but it can’t be discounted either. I saw this myself, one Sunday afternoon in Le Parc André Malraux in Nanterre. I was with Djamel, a high-spirited former ambulance driver, who was quizzing me about “la belle Amerique.” Beneath our feet were the remains of the bidonville, or shantytown, where many of the October 17 protestors lived for want of anywhere better. An eavesdropping stranger overheard Djamel speculate that social integration for Algerians and their French-born children might be easier in my country than it was in France; he sprang out from under the trees and interrupted our conversation. “Stop saying that!” he shouted, as if Djamel were an old adversary who would not listen to reason. He identified himself as an off-duty police officer, and he looked the part: tall and muscled with cropped blonde hair. A runner. He talked about “young hoodlums of foreign origin,” and the stubbornness of “those who elected to remain at the edges of French society rather than assimilate.” When Djamel ventured that he’d rather be a life-long immigrant than half a Frenchman — never accepted as truly “French” — the other man shouted him down. At last, Djamel, who grew up not far from where we stood but holds an Algerian passport, posed a terribly French question: He respected the stranger’s experiences and in the spirit of liberty, equality, and fraternity, why couldn’t he extend Djamel that same courtesy? In answer, the stranger laughed mirthlessly and jogged off.

IV.

All things being equal, there is a case to be made that lived history, like religion, is a private concern. “To each his own memories,” said the journalist Farid Aïchoune, who was arbitrarily arrested, aged 10, on October 18, 1961, in front of a maternity shop on the rue de Rivoli. “In the Kabyle Berber culture in which I was raised,” he told me, “there’s a belief that yesterday is dead. I have a horror of Algerian resistance associations where old mujahideens recall the struggle for decolonization with nostalgia. I was a child escapee … Enough! What need is there to talk about it?”

From the perspective of some who went through the Algerian War, perhaps not much. Yet the after-effects of France’s 130-year sojourn in Algeria continue to manifest themselves in divisive ways. The last time I was in Argenteuil, northwest of Paris — where in 1961 police tossed Algerians into the river — a modest narrow stela in memory of Audin had been vandalized, the glass case that held his photograph shot with hairline cracks. As Stora told me, “Some memories can be dangerous.”

We know that in troubled times societies turn against migrants and refugees as well as anyone perceived as the so-called Other. That is why the memory of episodes like the October 17 massacre matter. Writing about the Papon trial in The New York Review of Books, Robert Paxton noted that “deep social and historical changes had to take place in France” before the state could indict him. If that reconciliation pattern repeats itself, the full recognition of France’s past is all but inevitable. But if the pattern doesn’t repeat itself, if there is a rupture, then those horrific events, like the victims of the October 17 massacre, will dissolve into the river of forgetting. Either way, sooner or later the country will be obliged to ask another question with no easy answer. What happens to a confrontation deferred?

¤

Laurel Berger is a writer covering arts and culture in Washington, DC.

¤

Banner image: "Aubervilliers passerelle de la fraternité & plaque retuschiert" by Claude Shoshany is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

¤

[1] Paxton, Robert O, "Tricks of Memory," The New York Review of Books, November 7, 1991.

[2] "Vichy on Trial," Robert O. Paxton, The New York Times, October 16, 1997

[3] Le Monde digital archives, see M. Claudius-Petit, “LA BÊTE HIDEUSE DU RACISME EST LÂCHÉE,” https://www.lemonde.fr/societe/article/2011/10/17/archives-du-monde-1er-novembre-1961-debat-a-l-assemblee-sur-la-repression-du-17-octobre_1588085_3224.html

[4] Paris 1961: Algerians, State Terror, and Memory, Jim House and Neil McMaster, Oxford University Press, 2006

[5] Le Monde, https://www.lemonde.fr/societe/article/2012/10/17/francois-hollande-reconnait-la-sanglante-repression-du-17-octobre-1961_1776918_3224.html

[6] Force of Circumstance, trans. by Richard Howard, G.P. Putnam and Sons, 1965

LARB Contributor

Laurel Berger is a writer covering arts and culture in Washington, DC. Her website is www.laurelberger.tumblr.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Patient Observation of Human Beings

Fabien Truong’s book is a thoughtful, well-crafted ethnography that humanizes the faceless, amorphous “Muslim youth” of the French banlieues.

Writing Algeria

Kamel Daoud is a brilliant, indeed dazzling, thinker: his sharp turns in thought and language, as well as his subject matter, gave me motion sickness.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!