How Long Is the Shadow of Jim Crow?

Racism is an unchanging force, right? Not so fast, according to a Black activist who lived through Jim Crow.

By Jonah Goldman KayApril 20, 2022

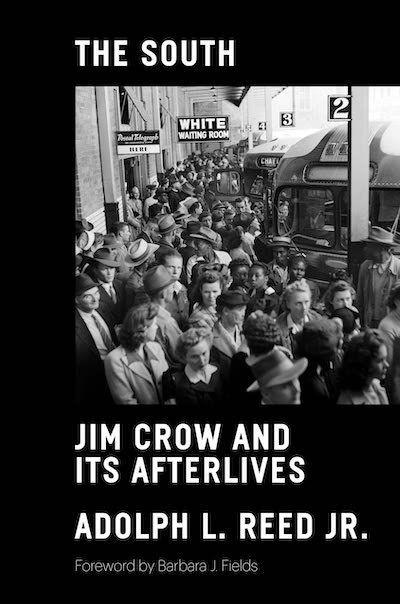

The South: Jim Crow and Its Afterlives by Adolph L. Reed Jr.. Verso. 160 pages.

WHEN HE WAS in ninth grade, Adolph Reed Jr. stole a bag of chips from a corner store in New Orleans. This was in late 1959 or early 1960 (he doesn’t quite recall), and Reed, like many teenage boys, was in a rebellious phase that involved shoplifting. His flirtation with petty larceny was short-lived — the shopkeepers, a white couple in their 30s, saw him palming the chips and pulled him aside.

In The South: Jim Crow and Its Afterlives, his memoir-cum-analysis of quotidian life under Jim Crow, Reed recalls the fear he felt when the couple caught him stealing. Like many Black teenagers growing up in Louisiana in the 1960s, his family and the surrounding culture had instilled in him the severity of his situation. The mere accusation of a criminal act from a white person could send him to the youth reformatory in Baker or, worse, to Angola, the state’s notoriously brutal prison. Luckily, the couple chose not to tell the police, instead giving Reed a lecture about the dangers of stealing and a warning that other shopkeepers might not be so kind.

However, Reed notes, the shopkeepers’ decision to subvert the strictures of Jim Crow in this specific instance reveals little about their overall character. That same couple could have ardently supported the Civil Rights movement, or they may have protested against school desegregation, which hit New Orleans later that year. “I know what would make for an uplifting story, but I have no illusions,” Reed writes. “All I know is that, if they had acted that afternoon in accord with the dictates of the Jim Crow social order and not seen me as they did, I could have, even with the relative insulation of class position, wound up at Baker.”

It’s this skepticism toward uplifting antiracism narratives that makes Reed a controversial figure. Throughout his career, Reed has opposed viewing race as a singularly important construct and racism as a historical constant. This “race reductionism,” as Reed calls it, flattens differences in class status and hinders the coalitions that bring progressive reforms. In recent years, the negative effects of race reductionism have been aggravated by some elite institutions, which have weaponized race for its profit potential and avoided economic policies that are unpopular with wealthy donors.

That approach (and Reed’s penchant for fiery quips) has led to its fair share of controversies. In 1996, Reed memorably described Barack Obama as a “smooth Harvard lawyer with impeccable do-good credentials and vacuous-to-repressive neoliberal politics.” More recent targets of his scorn include “woke culture” (“irrationalist race reductionism”), the Black Lives Matter organization (“careerist race ventriloquists”), and The 1619 Project (“a big sigh”). Not even the Democratic Socialists of America were immune: Reed and the New York chapter of the DSA were forced to cancel a scheduled talk after a vocal contingent opposed his politics.

In The South, Reed recounts growing up in New Orleans while blending in his analysis of segregation. Like his criticisms of Obama or The 1619 Project, Reed’s perspectives on Jim Crow are both incisive and incendiary. Some sentences, like the assertion that “[s]egregation was enforced on whites as well as blacks,” seem tailor-made to inspire a 280-character retort from certain corners of the left.

The experiences that Reed describes in The South were core to his ideological formation. Living in this contradictory system — one in which it would not be surprising for a white shopkeeper to treat a Black teenager with parental concern one day and lead an anti-integration rally the next — led Reed to oppose drawing a direct line between Jim Crow and contemporary racial justice issues.

Reed argues that those who see Jim Crow as a direct metaphor for the present fall into the trap of race reductionism. When New Orleans decided to take down its monuments to the Confederacy, which were built during the early years of segregation, many lauded the decision as a sign that the symbols of Jim Crow had been toppled. Reed, who happened to be in New Orleans at the time, recalls feeling frustrated with this logic. While the monuments valorized a despicable era, the decision to remove them was largely performative. Reed writes that it was a “rearguard undertaking” that appeased a neoliberal idea of multiculturalism while perpetuating “a social order that is sharply unequal for most.”

In other words, class-based inequality is the historical constant, not race. While the segregationist order applied to all Black people, its impacts were different depending on one’s class. As Reed reminds us, one of Homer Plessy’s arguments against segregated train cars, in the 1896 Supreme Court case that enshrined the “separate but equal” doctrine, was that these restrictions denied upper-class Black people the right to first-class accommodations.

While Reed objects to seeing racism as a historical constant, there are some systems that remain unchanged. Before moving to New Orleans, Reed lived with his parents in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, the nearest town to Cummins State Prison. During Jim Crow, prisoners at Cummins performed the same work as their enslaved ancestors, laboring on state-run farms and in municipal buildings without payment. Reed recalls passing Cummins State Prison on a road trip through Arkansas 40 years later:

That day in 1993, through the vaporous heat rising from the dusty soil, we could see off in the distance phalanxes of prisoners in their white uniforms lining up and working, overseen by mounted guards with shotguns — exactly as they would have appeared four decades earlier.

These recollections are underpinned by a sense of urgency. With each passing year, there are fewer Black Americans who remember the experience of living under Jim Crow. Memories of the interpersonal relationships — more human-scale and less easy to level with theory — fade as well. In seeking to preserve the echoes of these memories, The South follows a long record of attempts to understand the scars of history through personal experience.

During the depths of the Depression, the WPA Federal Writers’ Project sent writers to collect the stories of formerly enslaved people. Between 1936 and 1938, the Slave Narratives project transcribed firsthand accounts from more than 2,000 Black Southerners. Along with around 500 photos, these narratives represent one of the most comprehensive attempts to understand the experience of enslaved Black Americans before they passed away. The Slave Narratives and The South also share an immediacy and a specificity that come from the subjects’ careful attention to their conditions.

The intentions of the Slave Narratives project were pure, but major flaws in the interviews make it a complicated body of work. While there were a few Black employees working with the FWP, most of the interviewers who recorded the narratives were white. In some cases, the interviewers were descendants of landowning families who had enslaved those very same interviewees. This led subjects to wrap their stories in humor or other indirect forms of softened communication. Sometimes, interviewers twisted words to fit a nostalgic narrative of the “old-time Negro.”

Reed does not purport to serve as a spokesman for his generation: “I make no claim to generality, much less universality,” he writes. By mining his own memories of segregation, Reed avoids seeing the past as a general allegory for the present. The portrait he paints is not a straightforward narrative of progress toward a post-racial future, nor is it a pessimistic lament that sees racial oppression as an unchanging force. Rather, it is a narrative exploration of a single moment in American history, as experienced by someone who lived within it.

¤

LARB Contributor

Jonah Goldman Kay is a writer based in London and New Orleans. His writing has appeared in Artforum, The Nation, and The Paris Review.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Exploring Racial Imaginaries in Soviet Visual Culture

Yevgeniy Fiks’s new book offers a rare glimpse into the Soviet Union’s ideological views on race and Blackness.

The Struggle for Black Education: On Jarvis R. Givens’s “Fugitive Pedagogy”

An outstanding contribution to the history of Black education that focuses on the career of Carter G. Woodson.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!