The History of What We Do to Each Other: On Nayomi Munaweera’s “What Lies Between Us”

Nayomi Munaweera has written a second novel of real power and grace, says Melissa Sipin.

By Melissa R. SipinJune 28, 2016

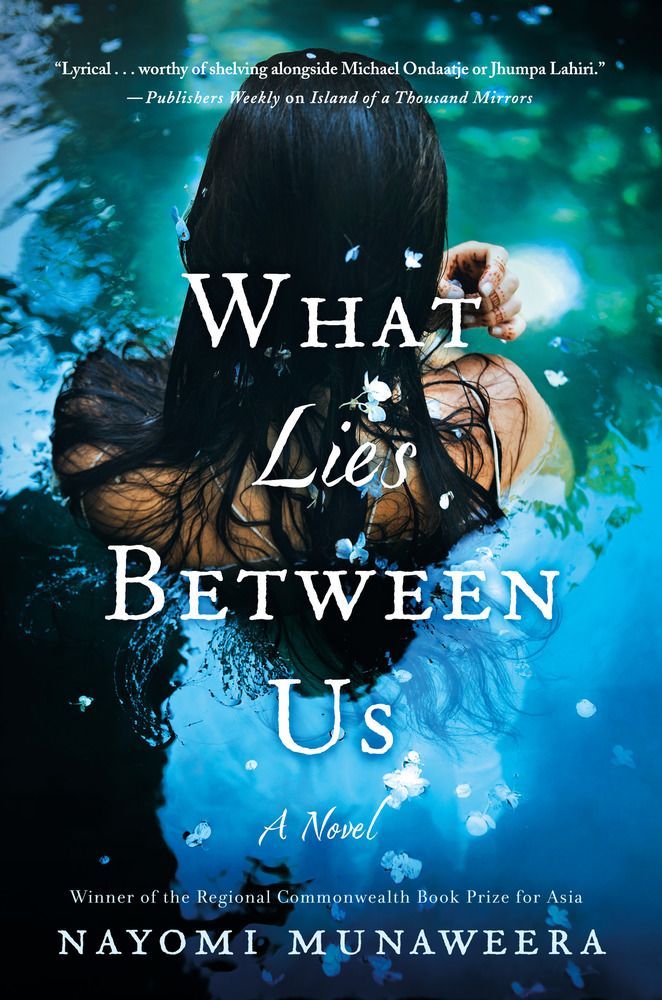

What Lies Between Us by Nayomi Munaweera. St. Martin's Press. 321 pages.

IN HER BRILLIANT, DEVASTATING second novel, What Lies Between Us, Nayomi Munaweera, winner of the 2013 Commonwealth Book Prize for Asia, unfurls the most sacred of human bonds — motherhood — by creating a character who does the worst thing a mother can do: killing her own child. This is a book about trauma, intergenerational and colonial trauma, but it is also about the sacrificial monstrosity of motherhood. It is a story that unfolds how trauma sinks into the bones and repeats itself, propagates, how it becomes parasitic. From the opening pages of its prologue, its transcendental mythologizing sets the stage and tone of the devastation that follows:

The moon bear is not just ancient and magnificent, it is also in possession of something treasured by humans. In Chinese medicine the moon bear’s bile is believed to remove heat from the body, curing tragic ailments of the liver and the eye. […] Some years ago, at a Chinese bile farm, a mother moon bear did something thought to be outside the realm of her animal nature. Hearing her cub crying from inside a nearby crush cage, she broke through her own iron bars. The terrified men cowered, but she did not maul them. Instead, she reached for her cub, pulled it to her, and strangled it. Then she smashed her head against the wall until she died.

Why do I tell this story? Only because it tells us everything we need to know about the nature of love between a mother and a child.

It’s a deft, electrifying portrait of the narrator’s fiery, verbal intensity; a voice born from a love of British novels and the need to mirror her academic, bookworm father. Munaweera is a storyteller whose lush and pregnant language disarms you with myths — myths of her homeland, myths of America, myths of motherhood, myths of her family, and myths of herself — and ties us to her indelible, painful confession.

Let me confess: It is hard to write about this book without emotion. As I finished it furiously, page to page, late into countless nights, it brought up many buried secrets within my own body: secrets, non-secrets, forgotten memory, made-up memories, necessary and questionable myths an abused child understands she must keep secret. As an artist who writes autofiction, I must confess again: I write about my mental illness, my diagnosis — Complex PTSD — and of my child abuse, of the molestations my body faintly remembers. Munaweera’s literary tour de force masterfully excavates the horrors of child sexual abuse and the compounding devastations it imprints on a lifetime, much like Hanya Yanagihara’s harrowing and beloved novel A Little Life. The difference between the two is this: What Lies Between Us ties the personal violation of the body — molestation — with the violent violation of history. It is a book that unravels how the child-abused protects herself, how she becomes the star immigrant daughter who achieves the American dream, but also how the past cannot be riven from her body even in a new, foreign land, how, again, trauma sinks into the bones and propagates in the life of the abused-child-turned-mother.

The narrator begins with her innate innocence: her childhood days on the hillsides of Kandy, Sri Lanka, the daughter of wealthy Sinhalese parents, a romantic coming-of-age story set in a sultry, tropical paradise. Though her mother suffers from an impairing depressive disorder and her father is a well-known university professor but also an alcoholic, this is otherwise an idyllic life: Sita, the kitchen maid, is the narrator’s dearest friend, and the gardener, Sita’s nephew Samson, is a protective, if somewhat embittered, guardian. A civil war rages across the country, in the north and the east, but our unnamed narrator spends her days swimming on the banks of the river, reading children novels from faraway lands where there is snow, a need for winter’s coats, and apples.

This picturesque scene is ruptured the day she is molested, a few weeks after her 11th birthday. In bold, severe strokes, the prose quickens its pace; the day her mother learns of her molestation, the narrator’s father and Samson die during a raging monsoon. Suddenly, she is taken from her tropical abode to an American suburb in the Bay Area, Fremont, California, where she and her mother take refuge with her aunt’s family. Here the novel echoes other immigrant bildungsromans: the sisterhood between cousin and American cousin, the talk of denim skirts and hiding seductive 1980s clothes underneath conservative ones, rocking out to Depeche Mode, desiring blonde hair, hairless legs, and then achieving the American dream: a scholarship to UC Berkeley followed by becoming a lifesaving ICU nurse. Even the headstrong falling in and out of love — with an ambitious, Southern-born visual artist — is a bittersweet sign of the narrator almost grabbing that fleeting immigrant dream. All of this occurs underneath the deep brush of the narrator’s lush voice, her raging desires, and her need to be seen and loved.

What sets this novel apart is its unflinching need to mythologize. With fluidity and finesse, the narrator confesses and transcribes her unnamable sin and bounds it to her home nation’s blood lust and desperate need to survive. In the beginning of the novel, she speaks of the British’s need to “domesticate and civilize” the island of Sri Lanka, a teardrop-shaped land mass at the tip of the Indian continent. She begins:

The last Kandyan king was fighting the British when his trusted adviser too turned against him. Enraged, the king summoned his adviser’s wife. His men ripped her golden earrings out of her flesh […] They beheaded her children and placed the heads into a giant mortar. They gave her a huge pestle, the kind village women use to pound rice, and forced her to smash the heads of her children. Then they tied her to a rock and threw her into Kandy Lake as the king watched in triumph from the balcony of the temple palace. Soon after, the British conquered Kandy and took over the island for centuries.

This is the history of what we do to one another. This is the story of what it means to be both a child of a mother and a child of history.

The unnamed narrator slips into postpartum psychosis, and her husband and his family begin to slowly abandon her, threaten to take away her only child. When her mother, who is thousands of miles away in Sri Lanka, reveals the damaging truths of her childhood abuse, she resorts to what her body only knows. In the end, she also confesses her name — a deity of the river — and says, “I bear the name of flowing water. A name that reminds us that all liquid is connected. In this way, each of us is bound, one to the other.”

Water is the gift of life, the mother of life. It is the first womb. It gives and takes away; it chooses what it gives, chooses what it takes. This is the power of mythologizing and of motherhood. The most primordial bond we have, that primal bond which determines everything that comes afterward, and it is a relationship awash in both the sacred and the damned. Munaweera’s daring novel will unnerve and devastate, open the heart and break it again, but with eyes wide open. It is a needed rupture, a devastating tale that happens in necessity and circumstance, just like childbirth, just like trauma, just like life.

¤

LARB Contributor

Melissa R. Sipin is a writer from Carson, California. She won Glimmer Train’s Fiction Open and the Washington Square Review’s Flash Fiction Prize. She co-edited Kuwento: Lost Things, an anthology on Philippine myths (Carayan Press 2014), and her work is in Glimmer Train, Guernica, Washington Square Review, Guernica/PEN Flash Series, VIDA: Women in Literary Arts, Eleven Eleven, and Hyphen magazine, among others. Cofounder of TAYO Literary Magazine, her fiction has won scholarships/fellowships from Kundiman, VONA/Voices Conference, Sewanee Writers’ Conference, Squaw Valley’s Community of Writers, and was shortlisted for the David T. K. Wong Fellowship at the University of East Anglia. As the Poets & Writers McCrindle Fellow in Los Angeles, she is hard at work on a short story collection and novel. More at: msipin.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Poetics of Trauma and Life After Rape: A Profile of Frances Driscoll

Frances Driscoll's poetry collections over the past 20 years deal explicitly with her life after rape and offer some answers to this question.

The Laius Complex. Abraham, Laius, Moses — Father, Trauma, and Carrying

A roundtable on the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze on the 20th anniversary of his death.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!