Histories of Violence: The Tragedy of Existence

Brad Evans speaks with Simon Critchley, author of “Tragedy, the Greeks, and Us.” A conversation in Brad Evans’s Histories of Violence series.

By Brad EvansApril 22, 2019

THIS IS THE 27th in a series of dialogues with artists, writers, and critical thinkers on the question of violence. This conversation is with Simon Critchley, who is the Hans Jonas Professor of Philosophy at the New School for Social Research. Simon is the author of many books, including, most recently, What We Think About When We Think About Soccer (Penguin Books, 2017) and Tragedy, the Greeks, and Us (Pantheon, 2019).

¤

BRAD EVANS: While tragedy has evidently preoccupied your thoughts and work for some considerable time, your latest book, Tragedy, the Greeks, and Us, provides your most explicit treatment of the concept. We know there is something deeply tragic about the human condition, and yet having read your beautifully written and richly provocative text, it is still apparent that there is so much to flesh out in terms of its philosophical relevance. Why did you feel it was now the right time in your life deal with this topic?

SIMON CRITCHLEY: Allow me to try and explain how I see things and why I think this is the time for a book like this, which has obsessed me for much of the last decade. The time is out of joint and something is rotten in the states we inhabit. We can smell it. Our countries are split, our houses are divided and the fragile web of family and friendship withers under the black sun of Big Tech. Everything that passed as learning seems to have reached boiling point. We simmer and feel the heat, wondering what can be done.

My book tries to confront where we are now, as Bowie might have said, by peering carefully through the lens of Greek tragedy. Tragedy presents a world of conflict and troubling emotion, a world where private and public lives collide and collapse. A world of rage, grief, and war. A world where morality is ambiguous and the powerful humiliate and destroy the powerless. A world where justice always seems to be on both sides and sugarcoated words serve as cover for clandestine operations of violence. A world rather like our own.

In my view, we have to try and make the ancients live again for our time. They hold up a mirror to us where we see all the desolation and delusion of our lives, but also the terrifying beauty and intensity of existence. This is not a time for consolation prizes and the fatuous banalities of the self-help industry and pop philosophy. Philosophy, as it is usually understood, is part of the problem, not part of the solution.

By contrast, I argue that if we want to understand ourselves better, then we have to go back to theater, to the stage of our lives. What tragedy allows us to glimpse, in its harsh and unforgiving glare, is the burning core of our aliveness. If we give ourselves the chance to look at tragedy, we might see further and more clearly.

This is what I think I’m up to. This book has been a long time coming and is the fruit of a kind of inversion of my views about the relation between philosophy and drama. I used to give classes decades ago at Essex on the philosophical interpretation of tragedy, from Plato through to Heidegger. This was hunky-dory, but it was at the expense of any proper consideration of the kind of thinking which we find in tragedies. So, around 10 years ago, I began to change the way I think about the plays of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides and to read them much more closely as a distinct kind of thinking, dialectical, staged, and deeply morally ambiguous, and to see them as a challenge to that kind of thinking which we habitually call “philosophy,” which begins in Plato with a ferocious exclusion of the tragic poets from the philosophically well-ordered city. So, I see this book as an extended undermining of the entire enterprise that we call philosophy. Namely, the philosophical prejudice that we can, with the use of reason, render intelligible being, or that which is, and on that basis, produce a series of moral imperatives about how to live. I see both those ontological and ethical assumptions as deeply flawed and limited. To counter them, I suggest very simply that we go back to theater and think through the kind of experience which it offers. Tragedy is ontologically opaque and ethically ambiguous.

What I find compelling about your understanding of tragedy is how it connects directly to question of meaning, and in particular, our self-realization of the insecure sediment of existence. In this regard, the tragic appears to have an intimate connection to the question of violence and what it means to be a mortal subject. How might we rethink the very idea of violence through the lens of tragedy and its philosophical premises?

It is in tragedy that we can track the history of violence that constitutes the apparently pacific political order. This is what happens in the Oresteia, say, where the democratic city — Athens — tells itself a story of its origins that flows back to the cycle of bloody revenge in the House of Atreus, where wife kills husband, son kills mother, and violence is only suspended through the violent fiction of law. Tragedy is largely motivated by rage that follows grief in relation to a situation of violence. The whole cycle of the Oresteia spins back to a mother’s grief for the murder or sacrifice of a virgin daughter, Iphigenia. A murder which is considered necessary by the Greeks, and by her father Agamemnon, in order to put favorable winds into the sails of the ships that will go to Troy to begin a 10-year war. Wherever one looks in tragedies, everything spins back to violence as the history and nature of the political order.

In your book, there is clearly a certain intellectual debt to both Nietzsche and Raymond Williams and the influential contributions they have made to our understanding of modern tragedy in particular. And yet you insist upon a closer reading of the legacy of more Classical Greek philosophy (notably sophistry) to stake out its more contemporary resonances. What is it about the Greeks that holds a special place in this drama?

I have become more and more obsessed with the ancient Greeks as the years have gone by. I find in these texts a life and liveliness which is very often absent from their modern epigones, perhaps with the exception of Nietzsche, to whom I owe a debt in this book, especially to the opening sections of Beyond Good and Evil. My book is close textual unraveling of some of the allegedly foundational texts of philosophy and what we call aesthetics, Plato’s Republic and Aristotle’s Poetics. I try and destabilize these texts through a careful reading. The thread that I pull on to do this is derived from texts by the Sophists, especially Gorgias, who come closer to the form of dialectical tragic thinking that I wish to recommend than much of what passes as philosophy. This book is primarily a defense of tragedy, but it is also a defense of sophistry against philosophy.

I’d like to bring this to the question of poetics and alternative styles for living. Nietzsche famously stated that we need art in our lives so that we don’t die from the truth. How do you understand the importance of art when dealing with the tragedy of existence?

Nietzsche is half right: we need art in order not to die from the truth of existence, but in my view only art is able to tell us the truth of truth. Namely, it is only possible to tell that truth in a lie, in the manifest deception that is theater. This perhaps reveals something interesting: namely, that we can only approach the truth indirectly in and through fictions which we know to be untrue. What those fictions present is the complexity and moral ambiguity of our existence, which is hard to bear and perhaps only bearable in the fiction of a play, a story, a myth.

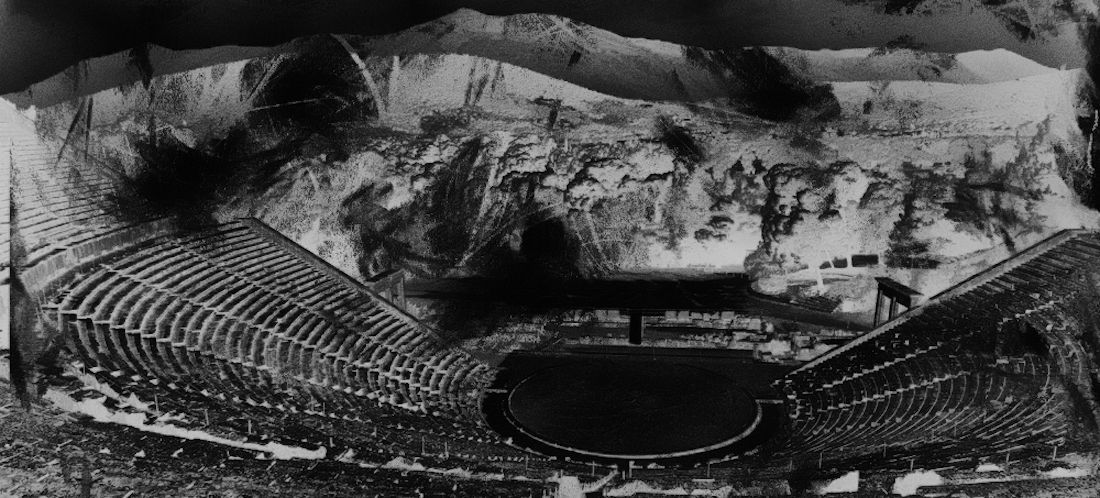

It’s important to remember that theater begins in the same place and around the same time as democracy, that prodigious ancient Athenian political experiment of basing a society on the idea of equality. But ancient Greek theater is not in any simple way a vindication or apology for democracy. Rather theater is the place where the tensions, conflicts, and ambiguities of democratic life are presented and played out in front of the people. It is the place where the multiple exclusions of Athenian democracy are staged: foreigners, women, and slaves. Theater is the night kitchen of democracy.

Questions of refuge, asylum seeking, immigration, sexual violence, and the duties of hospitality to the foreigner reverberate across so many of the tragedies. Theater is that political mechanism through which questions of democratic inclusion are ferociously negotiated and where the world of myth collides with law. Think of the Antigone, where the whole play is a conflict about rival claims to the meaning of law or nomos. Or the trilogy of the Oresteia, whose theme is the nature of justice and which even ends up in a law court on the Areopagus, the Hill of Ares just next to the Acropolis. Tragedy does not present us with a theory of justice or law, but with a dramatic experience of justice as conflict and law as contest.

In conclusion, what then is the infinite demand we can bring to tragedy in order to rethink what the political might mean in the world today? Or if we are to demand the impossible, might we not conceive of a philosophical orientation beyond the tragic?

Beyond the tragic for sure. I think the idea of the tragic is philosophy’s invention, especially the invention of post-Kantian thought in Schelling and Hegel. I try to both tell and undermine that story in the book. My recommendation is that we go back to theater, back to art and look and observe. We need tragedies and not the tragic. I would say the same thing about “the political.” The infinite ethical demand here might just be the old Wittgensteinian idea of “don’t think, look.” I want the reader to look at the ancient Greek plays or indeed at any plays — Shakespeare, Büchner, Ibsen — and to feel the pull of the aliveness which those plays animate without coming to any foundationalist or indeed principled moral viewpoint. What I see in the greatest theater is a kind of total honesty where we begin to radically question who we are and what we know, a full moral skepticism if you like. That, in our world of deafening moral certainties, would at least be a start.

¤

LARB Contributor

Brad Evans is a political philosopher, critical theorist, and writer, who specializes on the problem of violence. He is author of over 17 books and edited volumes, including most recently Ecce Humanitas: Beholding the Pain of Humanity (2021) and Conversations on Violence: An Anthology (with Adrian Parr, 2021). He leads the Los Angeles Review of Books “Histories of Violence” section.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Histories of Violence: When Art Is Born of Resistance

Brad Evans speaks with American artist Martha Rosler. A conversation in Brad Evans’s “Histories of Violence” series.

Histories of Violence: The Expulsion of Humanity

Brad Evans speaks with Columbia University professor of sociology Saskia Sassen. A conversation in Brad Evans’s "Histories of Violence" series.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!