Her Dark Materials: A Conversation with Vanessa Place

Daniel Elkind speaks to Vanessa Place about her provocative “You Had to Be There: Rape Jokes.”

By Daniel ElkindFebruary 5, 2019

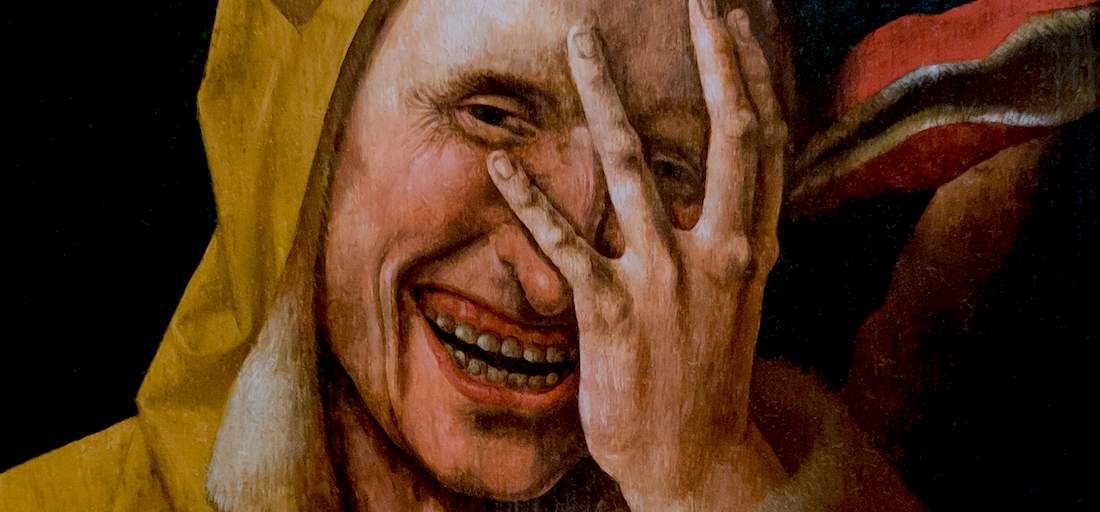

RAPE JOKES aren’t funny. What to make, then, of Vanessa Place’s new book, You Had to Be There, which collects such jokes but is not a joke book?

Place is a poet, performance artist, and criminal defense appellate attorney representing convicted sex offenders who can’t afford a lawyer. She has previously written about her work in The Guilt Project: Rape, Morality, and Law (2010). Culled, according to Place, from 4chan, Sickipedia, and other musty online corners, the jokes she has woven together here — and, in some cases, written herself — unspool over 130-plus pages with no editorial commentary aside from a foreword (by Dave Hickey), an afterword (by Natasha Stagg), and a brief artist’s statement. Though there’s an undeniable logic and rhythm to the unspooling, readers will be forced to navigate Place’s text (or “verbal artifact”) on their own, without the usual niceties. This is a potentially terrifying, but perhaps also liberating, experience for readers coddled by the gatekeepers of predictability — one that makes commentary of either stripe seem perfunctory, a failure “to go beyond either condemnation or understanding.”

“The structure of a joke, according to Freud, is that it is a sudden discharge of repression, often sexual, often kind of obscene,” Place has written. “And so, in that way, the joke itself ends up being structured, or ends up having the same structure, as a rape — a violent discharge of repressed sexuality.” Laughter is implicative, and you almost have to laugh or stifle your discharge. But these are not jokes that rely on laughter to complete them. When she performs the piece, Place neither greets nor thanks the audience, training the spotlight on the crowd while she remains in the shadows. “So ... joke’s on you.” It’s an apt analogy for a book in which readers are both in control of turning the pages and forced to participate in their own discomfort as they do so, particularly in an era in which “aren’t we all complicit?” has become a dinner party cliché. It reminds one of the kind of incisive critique Conceptualism is still capable of — as a cultural intervention, a mirror for examining parts we’d prefer not to see.

I queried Place via email, and she responded graciously. We spoke about comedy, consent, the worship of mastery, and the audience as a potential witness rooted, as Place puts it, in “the gorgeous muck of their desire.”

¤

DAN ELKIND: I can imagine that some people browsing the Humor section won’t be amused to find this book shelved next to Jeff Foxworthy or whatever. Is there an appropriate section? Where would you shelve it?

VANESSA PLACE: Museum bookshops and home toilets.

This piece was inspired by the debate about rape jokes in stand-up comedy. What was your initial reaction? Did you take it as a challenge?

The hivemind response — and we could take some time to think about why this is currently a term of approbation — was that rape jokes are categorically not funny. I thought that this was wrong: they are funny, but funny contextually. The more interesting question became: Why, and under what conditions? If one rape joke is told by way of shock or solidarity, what happens if 250 jokes are told, and told publicly, in a voice that is not supposed to tell?

The book’s disclaimer states that this is a text version of a live performance — “art performance, not stand-up comedy.” What would you say is the fundamental difference between the two?

Stand-up comedy is meant to get a laugh; art may get a laugh, but that’s not a predicate for the practice. Stand-up comedy is typically performed as a kind of intimacy, the performer doing a bit of prefatory audience-banter, couching the gags conversationally, as if speaking, as if telling something about themselves, as if revealing. Art performance is formalized as a performance: for me, I do not speak to the audience, neither greeting nor thanking them for their attention. The material is read from a text, recited without affect, and is more or less obviously impersonal material. Representatively, as a matter of disciplinary practice. After all, I’m wearing a suit, and sometimes a nice tie.

You’ve said that this piece allows you to observe the audience. What has the response been like? Have you noticed anything that surprised you?

I’m never surprised, except by love.

Your performance seems to say that honest emotional responses are mysterious. The laugh you’re going for is the involuntary kind. I’m a Jew and found myself laughing most at the Jewish pedophile jokes, and then nervously laughing about that.

What’s the question, then?

Touché. You’ve also said that there’s no such thing as rape culture: “It’s just culture.” I imagine you mean everything from catcalling to “conjugal debt.” Can you elaborate on that?

I’d be even broader, so to speak, in my claim. Structurally, at least here, at least now, at least in our insufferable present, we are enthralled by mastery. Even if we don’t like a particular master, we believe ourselves, or our preferred designees, capable of being some better master. Mastery itself is not questioned, meaning the real question of domination and submission is not questioned. It’s like the cops: you may think you hate the cops but simultaneously think they should be on the scene of what you consider a crime, and will self-deputize to police others, such as with call-out culture.

This suggests that we want these structures, and again, the question then becomes why. A culture that loves mastery will have many masters, some in balaclavas, some in blue suits, some with a lot of online followers. Of course, we are predisposed to recognize certain demographics as embodying mastery more than others, and may rail against the particular manifestations of this, but that’s debating interior design, not architecture. As an easy example, many people ask me whether I’ve ever been raped, and those more psychoanalytically affined ask if I want to be, but no one asks me if I am, or want to be, a rapist. That’s just culture.

For a long time the law defined rape as nonconsensual intercourse with a female that was not one’s spouse. As a practicing defense attorney, how do you see this gap between social and cultural mores and the legal code?

Rape is not a thing, rape is a verdict: there has been some judicial determination that a sexual encounter was nonconsensual. This can lead to the woman being raped — i.e., having had an encounter that she did not consent to — and the man not being a rapist — i.e., he did not know or understand that there was no consent. The gap appears when we level the categories, such that every unwanted encounter is deemed rape, regardless of its indeterminacy. Put another way, I could consent to something in the moment, then reconsider, realizing that my then-consent was the result of various pressures, prejudices, fears, et cetera, and decide, or understand, at least to myself, that the encounter was nonconsensual. This is a subjective historical process rather than a retroactive historical fact.

Put still another way, it would perhaps be better if Americans were less Protestant in our thinking about sex: rather than insisting on a kind of subjective purity on both sides, marked by virginal intent, we could operate from a colder, dumber objective politeness. If I am scrupulous in treating you with respect, do you care very much if I think you’re a fuckwit? Or if you mean nothing to me? Mores are not morals, nor should they be.

I recently read something Kurt Tucholsky said about Soviet Russia: that the “November 7 demonstration on Red Square […] reminded him of an Easter procession in Rome, a kind of state religion in which a humanitarian ideal had been turned into a new tyranny.” Do you think political correctness or whatever you want to call it has become a humanitarian ideal turned orthodoxy? Does laughter constitute heresy?

Laughter signifies nothing but ideology: we laugh because we agree, wholeheartedly, or because we agree, ironically, with the ideological donnée. The right is nostalgic for the past, the left is nostalgic for the future. What’s funny about that? Everything.

Besides provoking an honest reaction, is there anything that you would like readers to take away from this experience?

I would be happy if they didn’t take anything away, if they could simply stay in the gorgeous muck of their desire.

¤

Daniel Elkind is a writer and translator living in San Francisco.

LARB Contributor

Daniel Elkind is a writer and translator living in San Francisco.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Death and Its Souvenirs: On Murderabilia

The disappointing art of murderabilia.

Toward a Humor-Positive Feminism: Lessons from the Sex Wars

Building a humor-positive feminism.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!