Heady Politics in the Ton: On Shondaland’s “Queen Charlotte”

Leigh-Michil George reviews Shondaland’s “Queen Charlotte,” and asks about the nature of the game being played.

By Leigh-Michil GeorgeJuly 17, 2023

EVER SINCE I watched “An Affair of Honor,” the fourth episode of Bridgerton, I’ve had a sense of foreboding. About a third of the way through the episode—the point in the plot where “boy loses girl”—Simon Basset, the Duke of Hastings (Regé-Jean Page), is reprimanded by the Lady Danbury for walking out on the flawless heroine, Daphne Bridgerton (Phoebe Dynevor). Daphne has been chosen by Queen Charlotte (Golda Rosheuvel) to be the ton’s “diamond of the season.” Lady Danbury, played exquisitely by Adjoa Andoh, is the matriarchal figurehead of the ton; she scolds the Duke for his arrogant dismissal of the ton’s conventions—its seasons, its courtships, and its marriages: “Look at our queen. Look at our king. Look at their marriage. Look at everything it is doing for us, allowing us to become. We were two separate societies, divided by color, until a king fell in love with one of us. Love, Your Grace, conquers all.”

Lady Danbury’s speech is stirring, but at the same time troubling. The Duke understands that, because of his skin color, his elevated position in society is “hanging on by one very loose and tenuous thread.” His wealth and status are subject to the whims of a mentally unstable King George III (James Fleet). The Duke’s response to Lady Danbury is swift and sharp: “Love changes nothing.” But, of course, he is wrong. Love changes everything. He’ll marry Daphne, and they’ll have a biracial baby. Love wins. Love unites. Love conquers all—even structural racism. But how does love conquer, exactly? To state the question in more precise terms, as Helen Thompson has, “how would George III, by marrying Queen Charlotte in 1761, reverse white supremacy entrenched in a social and economic system fueled by empire?”

When Bridgerton, based on the eight-volume series by Julia Quinn, first premiered on Netflix in December 2020, it transported Shondaland’s “color-conscious” casting to a Regency setting, and many viewers, including myself, found the show enticing. I found its premise vaguely empowering—a mixed-race Queen Charlotte reigns over the British empire (inspired by creator Chris Van Dusen’s discovery that some historians believe Charlotte had African ancestry). Until it strained my willing suspension of disbelief. A white royal marries a Brown princess and suddenly 18th-century Great Britain is a racial haven. Uh huh.

Nevertheless, many still find Bridgerton’s premise unproblematic—it has always billed itself as escapism, after all. Sometimes, though, I have found Bridgerton’s escapism to be anxiety-inducing. Instead of reassuring me, the show’s Regency romance version of racial inclusivity sometimes loops back around to remind me, a woman of color, that I’m hanging on by a very loose and tenuous thread in present-day America’s racial political scene. As Salamishah Tillet has observed, “[D]espite Lady Danbury’s beliefs that love conquers everything, I could not help but think that history ends up validating the duke’s skepticism and his sense that Black progress is always a fragile thing.” I couldn’t fully lose myself in Bridgerton’s gorgeous fantasy of Black and Brown empowerment because I couldn’t wrap my head around its counterfactual history. There were too many questions left unanswered. Like Tillet, I wondered, “Maybe if I knew how Lady Danbury or Queen Charlotte came to be, I’d be so convinced that I’d finally be able to revel in a past that I haven’t quite seen myself in before.”

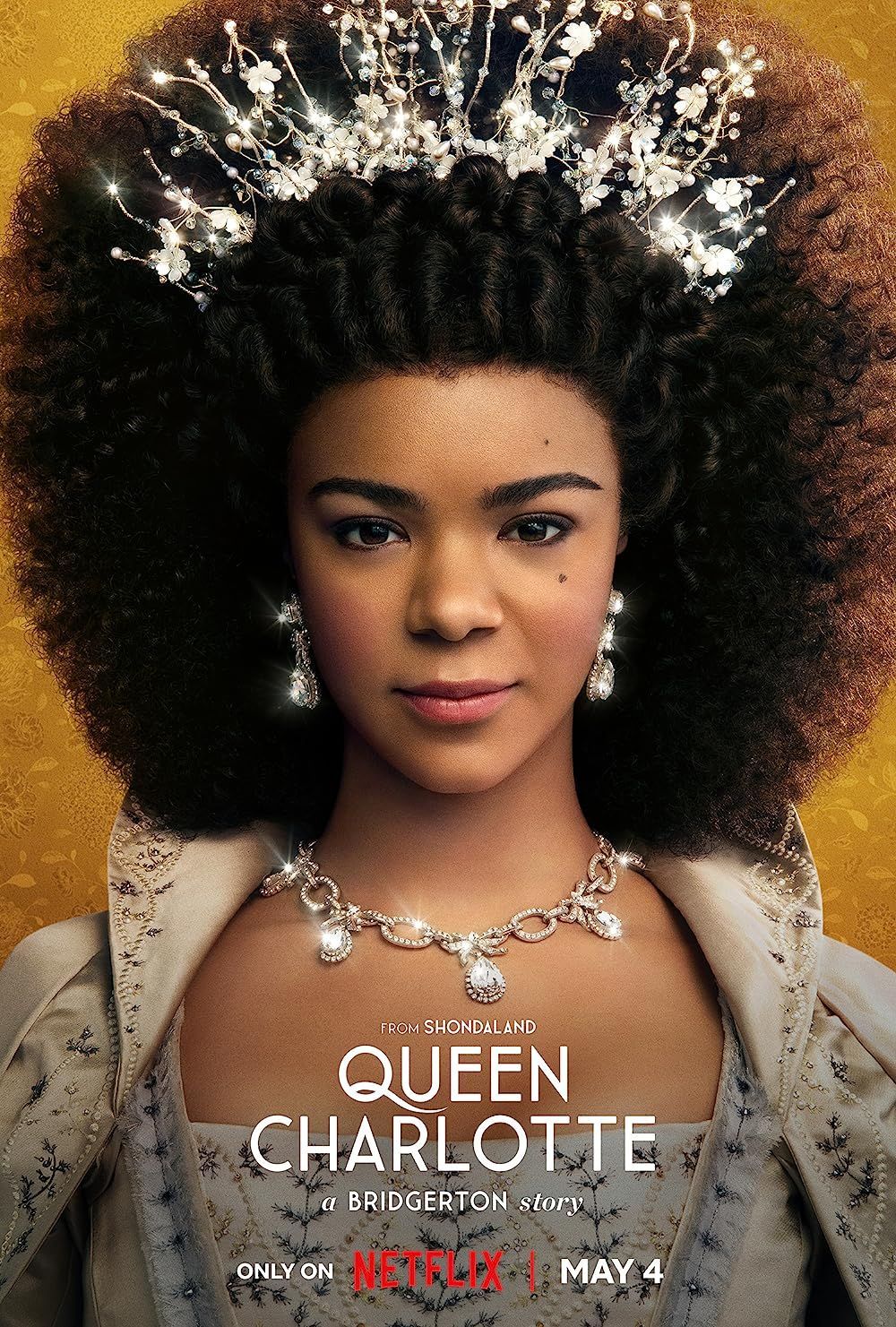

As if in answer to our question, the six-episode prequel released this spring, Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story, gives us more about how Lady Danbury and Queen Charlotte came to be. Set in 1761 on the eve of Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz’s marriage to King George III, the show recreates the core fantasy—the lavish settings; the sumptuous costumes; the glamorous, over-the-top hairdos; and the hot, steamy sex scenes—that made the first two seasons of Bridgerton so successful and fun too. The prequel is directed by Tom Verica and written by Shonda Rhimes herself (episodes four and five were co-written with Nicholas Nardini). India Amarteifio’s performance as the young Queen Charlotte is remarkable; she has the poise and panache, the imperial glare and royal swagger, captured so brilliantly by Rosheuvel’s older Charlotte. Amarteifio is paired perfectly with Corey Mylchreest, who plays the young king. The actors deliver an alluring mix of sharp-witted repartee and sexual chemistry. But what is most compelling about the co-stars’ performances is the vulnerability they each convey, as the King’s mysterious illness increasingly threatens the stability of their marriage and the kingdom. In her role as young Agatha Danbury, Arsema Thomas captures the sagacious charm and sociopolitical acumen of the older Lady Danbury. The sudden rise, intermittent dips (there’s no really big fall), and eventual triumph of Charlotte and Agatha, which is, for the most part, engaging, has garnered the show generally favorable reviews.

Even while it retreads familiar story arcs, the spin-off series veers forward in at least one unexpected direction. A subplot concerns the lusty, tender romance between two upstairs servants: Brimsley, the Queen’s Man (Sam Clemmett), and Reynolds, the King’s Man (Freddie Dennis). Bridgerton has been accused of queerbaiting, so it’s both surprising and refreshing to see queer love, albeit closeted, depicted in Queen Charlotte. But the Brimsley-Reynolds couple also underscores the contradictions of the Bridgerverse: racism is seemingly a thing of the early Georgian past, but not homophobia or sexism.

In Queen Charlotte, racism is explicitly addressed and implicitly erased. The explanations it gives are too pat and simplistic; as might be expected, the show doubles down on its romanticized approach to structural inequities. When Charlotte first arrives in London, she is icily assessed by her future mother-in-law, the Dowager Princess Augusta (Michelle Fairley). The Queen Mother inspects Charlotte’s teeth, her hands, and her hips, then rubs Charlotte’s face, as if the color of her skin is a dirty mark that can be wiped clean. But the color doesn’t come off, to Augusta’s dismay. Later, she confers with the royal advisors. Charlotte is “very brown.” They are all momentarily stumped by the problem of the color line. A beat later, though, Princess Augusta arrives at a solution: “We are the Palace. A problem is only a problem if the Palace says it is a problem.” Augusta will invite Black and Brown folks to the royal wedding and grant them aristocratic titles—and just like that, her impromptu intervention, dubbed the “Great Experiment,” will transform British society.

The fantasy of Shondaland’s Bridgerton is that the indecencies and injustices associated with racism are quickly overcome by a combination of true love, high fashion, and soft power. The same holds true for Queen Charlotte. When the newly titled Lady Danbury throws the first ball of the season, she scans the segregated room. Nothing really seems to have changed; it is still her side versus their side. But then the King and Queen arrive at the ball, the royal couple dances to a classical rendition of Alicia Keys’s “If I Ain’t Got You,” and the two separate societies, divided by color, very quickly come together. Later that evening, George informs Charlotte, with “one party, we have created more change, stepped forward more than Britain has in the last century.”

Just like that. Uh huh.

Alongside these sweeping gestures and statements, there are gaps and silences whenever talk of empire, trade, or the colonies comes up. The sway of empire is underscored by Charlotte’s brother, Duke Adolphus (Tunji Kasim). When Charlotte first learns that she must marry the British monarch, she asks her brother why. He replies, “[T]hey are the British empire. And we are a tiny province in Germany. We had no choice.” In a later scene, Earl Harcourt (Neil Edmond), one of Princess Augusta’s advisors, reminds her of the trade deals they have with the German province. But what exactly is being traded? More than once, the colonies are mentioned. Which colonies? Is it those 13 colonies, like Massachusetts and New York, who will in a few years be fomenting rebellion under the banner of “No taxation without representation,” or is it the Caribbean colonies, like Jamaica and Antigua, with their large sugar plantations, an immense source of wealth for absentee British landlords? Like the first two seasons of Bridgerton, Queen Charlotte leaves many blanks unfilled. So, when the Queen and Lady Danbury take their tea, we don’t know for certain where the sugar that sweetens their cups comes from. But the most likely source is Jamaica.

In the second half of the 18th century, Jamaica was Britain’s most profitable sugar colony. The amassed riches created a highly stratified society in which wealthy elites, including some mixed-raced Jamaicans, financially benefited from the gross inequities built into what was, arguably, the most brutal slave regime in the British West Indies. However, in 1761—the same year in which most of Queen Charlotte takes place—the Jamaican assembly passed a law restricting how much money a person of color, born out of wedlock, could inherit. The amount was 2,000 pounds, which was “a large sum, but relatively modest compared to the substantial sugar fortunes of many planters,” as Daniel Livesay documents in Children of Uncertain Fortune: Mixed-Race Jamaicans in Britain and the Atlantic Family, 1733–1833 (2018).

In Queen Charlotte, though, holding on to generational wealth isn’t the real issue for people of color, like Lady Danbury. “We already have money,” she tells Princess Augusta. “We have more money than most of the ton.” Furthermore, Agatha Danbury, like her husband, is descended from a royal line in Sierra Leone. (The novelized version of the series, co-written by Quinn and Rhimes, indicates that the family wealth in Sierra Leone comes from diamond mines.) Rather, the problem for Lady Danbury and other aristocrats of color is how to get their men accepted into the right clubs, like White’s, and their sons admitted to the right schools, like Eton. Aristocrats of color, in Bridgerton, face many of the problems that upper-class Black people in 21st-century capitalist America might face. When Lord Danbury eventually attains his place at White’s—the pun is never noted by any of the characters, but it’s hard to overlook—I couldn’t help but wonder what kind of “cut direct” or snub he must have endured upon his entrance into the formerly all-white White’s. We never see this scenario play out. In the first season of Bridgerton, there is a passing reference to slavery: the Black boxer, Will Mondrich, is the son of a formerly enslaved man who was freed for fighting on the British side during the American Revolution. But slavery is never mentioned in Queen Charlotte.

Of course, Queen Charlotte is not a “history lesson.” We learn this in the opening frames. “It is a fiction inspired by facts.” And it leans into certain facts more than others. For example, the real Queen Charlotte and King George III had a relatively happy marriage that produced 15 children, with 13 surviving into adulthood (though only 12 were still alive after 1810)—a fact the show accurately represents. In one major storyline, set during the Regency, the older Queen Charlotte has a royal crisis on her hands because her five daughters and seven sons have failed to fulfill their obligations to the Crown. The Queen’s eldest son, George, Prince of Wales, has produced a royal heir, but that daughter dies tragically while giving birth to a stillborn child. None of the Queen’s remaining grandchildren are legitimate heirs; she bluntly refers to her grandbabies as bastards. With characteristic vim, Rosheuvel’s Queen Charlotte rebukes her children, “virgins to the left of me, whores to the right.” Unfortunately, none of the children can match their mother’s wit. Even Prince George—he is the Regent, whom the period is named after—is rather lackluster. It is a fact, though, that the prince, eventually King George IV, was a flamboyant, controversial royal figure. But he, like the rest of his Hanoverian siblings, is presented in rather one-dimensional terms. Surely, a missed opportunity.

It isn’t all that interesting to watch the Queen’s children spend an inordinate amount of time airing their grievances about being treated unfairly by their mother, it turns out. Curiously, this biracial brood doesn’t appear at all concerned about the precarity of their mixed-race background or how the royal crisis might jeopardize the racial advancements of the Great Experiment. They simply don’t discuss it.

All this makes the Duke’s concerns in Bridgerton about that very loose and tenuous thread seem even more troubling in Queen Charlotte, especially since we now know that his dukedom stems in part from a whim of Princess Augusta, who is problematically depicted as both sympathetic racist and white savior. We now understand why Lady Danbury was so dismayed by the Duke’s lack of gratitude, and why her plea to him was so passionate: for over 50 years, she has been playing the game, sustaining the Great Experiment, knowing full well that in this united kingdom there are still sides. And the rules of the game are that when one from her side (Simon Basset, a Black man) marries one from their side (Daphne Bridgerton, a white woman), it’s a win for the people of color. These rules aren’t made clear in Bridgerton, but in Queen Charlotte, they are. When Lady Danbury first attempts to have her son Dominic recognized as the next Lord Danbury, in order to carry on the family line after the sudden death of her husband, her request is ignored by Princess Augusta. Lady Danbury is disappointed, but not deterred; she instructs the boy in his noble heritage: “[Y]ou will take your rightful place because you are entitled to it […] You are the son of Agatha Danbury, born name Soma, Royal Blood of the Kpa-Mende Bo Tribe in Sierra Leone. You come from warriors. We win.” The boy must never forget to hold his head high like the warrior he is, and he must always remember his duty to hold onto his lordly title.

Behave. Do your duty. Follow the ton’s rule. These racially coded strictures might strike us as the color-conscious Regency England equivalent of respectability politics, as Patricia A. Matthew has inferred. They also reveal the limitations of both Bridgerton’s and Queen Charlotte’s escapist fantasies of Black and Brown empowerment. The white gaze is still there, disciplining and surveilling the melanated members of the ton.

Even still, Shondaland’s version of Queen Charlotte should be celebrated for what it does offer us. Gorgeous hair. Piled-high wigs. The loveliest Afros you’ve ever seen. This is something I should have understood years ago when Bridgerton first aired. But it was only after watching the opening sequence of “Honeymoon Bliss,” the second episode from Queen Charlotte, that I accepted this truth. When the young Queen began her elaborate morning dress routine, I scrutinized her head. Suddenly, I felt a sense of foreboding. My stomach churned. I was very concerned about Charlotte’s hair. What sort of injustice was I about to witness? It didn’t look like any of Charlotte’s servants, who were all white and presumably British, knew how to care for her kinks and coils, let alone shape it into a bejeweled tower of curls. I was wrong. And that, dearest gentle reader, as Lady Whistledown would say, is a fact. In one frame, Charlotte’s hair is naturally beautiful, but disheveled. In the next, it is coiffed into perfection. The ultimate fantasy. At last, I can revel in a past that I haven’t quite seen myself in before. Look at our queen. Look at everything she is doing for us, allowing us to become. Queen Charlotte operates according to this simplifying yet heady politics of escapism. Our hair rules the ton. We win.

¤

LARB Contributor

Leigh-Michil George has a PhD in English from UCLA and an MFA in screenwriting from American Film Institute. She teaches in the English department at Geffen Academy at UCLA. Her writing has been published or is forthcoming in The Rambling, Fine Books & Collections, and Eighteenth-Century Fiction.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Sex and Social Isolation: The Writing Sex Series During COVID-19

Jonathan Alexander reflects on the interviews he conducted for LARB’s Writing Sex series.

On “Mission: Impossible” and Unaccountable Government

With its seventh installment looming, Pat Cassels details the way the “Mission: Impossible” franchise became an unlikely chronicler of American...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!