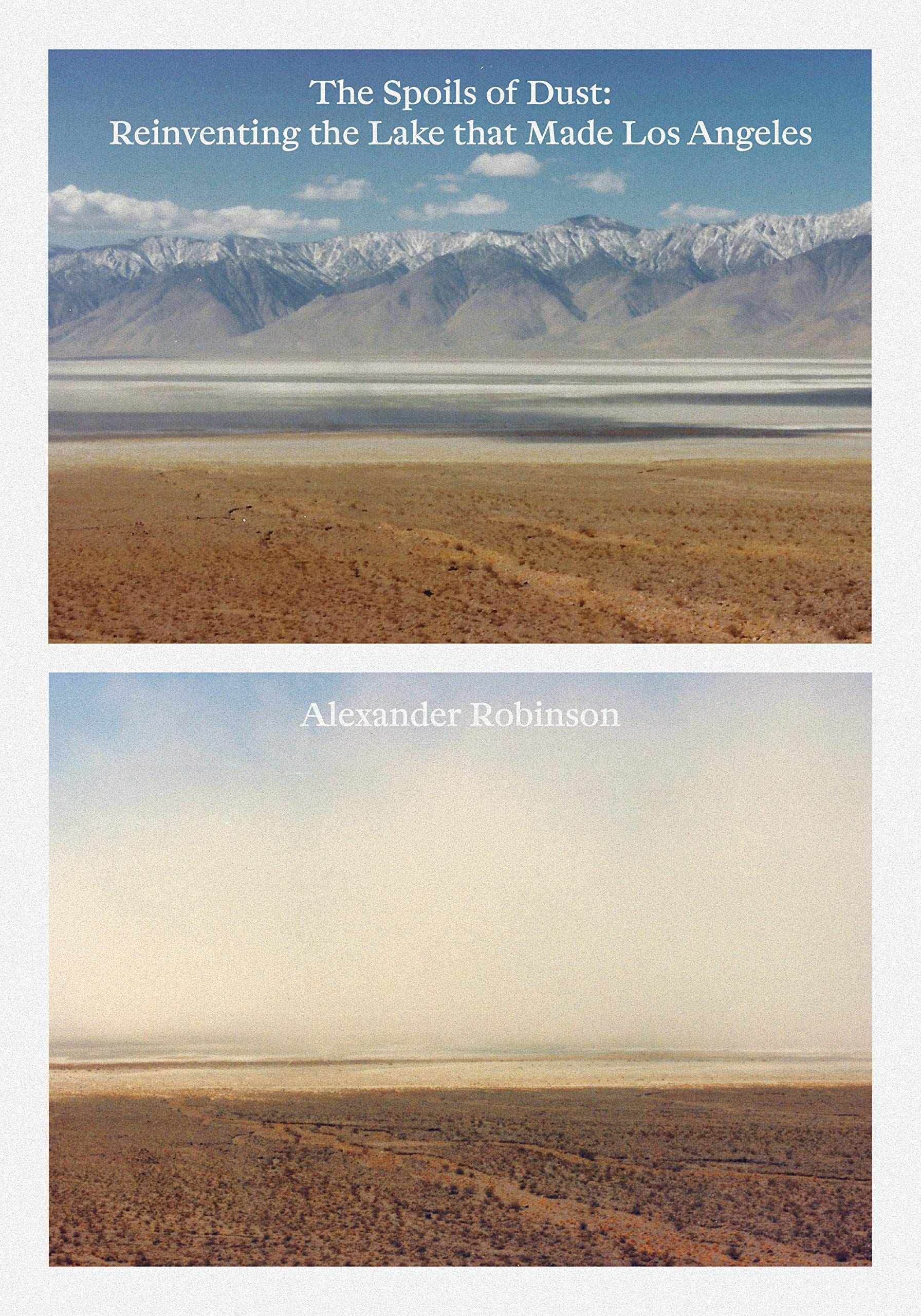

Have Your Dust and Eat It: On Alexander Robinson’s “The Spoils of Dust: Reinventing the Lake that Made Los Angeles”

A book about one of Los Angeles’s biggest historical embarrassments calls for a new way of seeing it as beautiful.

By Peter Sebastian ChesneyApril 4, 2019

The Spoils of Dust by Alexander Robinson. Applied Research & Design. 256 pages.

FEW WOULD BE SHOCKED to learn Los Angeles bears responsibility for some of the worst air quality government regulators have measured in US environmental history. More surprising is where these P

10

or “coarse particulate” measurements were recorded. Nowhere near a freeway, a farm, a factory, a landfill, or even the city itself, the numbers came from about 160 miles north of Los Angeles. The culprit: Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) infrastructure. After the city desiccated the Owens Valley landscape, a seasonal alkaline water body named Owens Lake had become the source of an intermittently billowing dust cloud.

The “rape” of Owens Valley should sound familiar to readers of Californiana. Morrow Mayo’s 1933 Los Angeles, Carey McWilliams’s 1946 Southern California: An Island on the Land, Robert Towne’s 1974 Chinatown screenplay, and Marc Reisner’s 1986 Cadillac Desert each successively outdid the last in condemning Los Angeles for a litany of sins against the hinterlands. Unlike moralizing contributions to the long Progressive Era’s anti-urbanist tradition, 2018’s The Spoils of Dust: Reinventing the Lake that Made Los Angeles establishes not only a case for reparation but also a path toward achieving just that. According to USC landscape architecture and urbanism professor Alexander Robinson, design allows for reinvention as restitution.

Robinson’s case hinges on crafting three books in one volume: an environmental history, a landscape atlas, and a speculative research project. Rejecting tropes of decline, Spoils extracts from the recent history of Owens Lake “a model for how, in today’s world, we might add value to landscapes irreparably altered.” Robinson then shows how to achieve this end by mapping a variety of embodied perspectives within a space that is “half-landscape, half-machine.” Thus data, not subjective aesthetics alone, call for imaginative solutions involving insights from both engineers and designers. Surely many scholar-collaborators will seize any excuse for another grant application, but this here is an obvious occasion for interdisciplinary work.

The product of Robinson’s fieldwork from several seminars, Spoils unfolds in 12 chapters. Part one, “The Lacustrine Mandate,” establishes a historical context. Readers will discover how dust control policies forced LADWP to reallocate water for partial restoration of Owens Lake. Part two, “A Prismatic Reckoning,” explores sensory dimensions from expert and casual experiences with data collection in this space. Part three, “Projecting Forward,” calls for a third way to see Owens Lake, neither subjective nor objective. Robinson instead hails readers, whether policy-makers or landscape designers, to highlight a “middle ground” in making an image of the lake with focus on the foreground, the background, and sights between.

The book concludes with an “Interface for Dry Lake Design” illustrating Robinson’s historical and cartographical work through the possibilities of gameplay. The Rapid Landscape Prototyping Machine (RLPM) is a proposed application that equips users to create patterns and to have machinery remotely mark them onto the dry lake bed. Think of RLPM as an ambitious version of the popular Kerbal Space Program: a game where players can plan and execute highly realistic, yet simulated, space flight missions. Just as a mistake in Kerbal leads to mission failure, RLPM is arranged to teach users structural limits to design in such space. Users can alter Owens Lake, but they cannot interfere with the area’s ecology or functionality as infrastructure.

Altogether, Spoils testifies to possibilities for academic monographs, even those in print, to operate much like interactive gaming experiences. Robinson’s book resembles a 1972 masterpiece of design criticism, Learning from Las Vegas by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour. Much like the circumstances leading to Learning, Robinson took landscape architecture students into an unlikely destination. There, open-ended pedagogy let students playfully document a multiplicity of perspectives vis-à-vis a supposedly dead space. The fruit of this method is gorgeous visuals of the unexpectedly rich middle grounds between foregrounds and backgrounds known as barren.

Just as helpful as the visuals is the work from theorists who show this intervention is open to readers who might do something other than landscape design. In Spoils, Robinson mobilizes a critique of visual culture, heavily indebted to James C. Scott’s observation that there is a “whole world lying ‘outside the brackets,’” which can shatter any sense of primacy for either top-down or bottom-up points of view. Having thus widened fields of possibility for authorship, Robinson takes an insight about seeing from cultural historian Alan Trachtenberg. For photographers, the images they craft have the capacity to capture both objects contained within and the “act of seeing” or the sightline from either a distant or a close physical (and social) position.

Carefully attending to perspective, Robinson traces and thus exposes sightlines that often go unnoticed among the broader scholarly community. One example is the weapons engineer’s point of view, oftentimes such a closely guarded secret scholars hardly even know where to find sources for this topic. Dust storms emanating from Owens Lake forced officials from the China Lake Naval Air Weapons Station and the Edwards Air Force Base to come out of the closet. Having had to ground flights and miss precious hours for testing experimental rocketry, these Cold War military installations sponsored dust studies and even published results in 1986. LADWP could dismiss local concerns, but defying the US Air Force proved a bridge too far.

Another sightline belonged to settler colonists who seized control of Owens Valley from Native Paiute-Shoshone people. History often obscures that white killing and taking laid the foundations for white power and privilege. Not so for LADWP when arguing before regulators that Owens Lake’s shoreline once fell below the level the EPA enforces. Testifying in 2012, archaeologists-for-hire presented evidence of a massacre inside the lake, which proved its smaller natural size at the time of the 1860s Owens Valley Indian War. Weighing costs and benefits, Los Angeles willfully assumed the moral burden of a massacre in exchange for a possibility of this favorable ruling on how much water LADWP needed to use for maintaining Owens Lake.

As much as I appreciate these anecdotes, for they provide scholars with leads for new and additional research, I found Robinson’s decision not to extend much critical attention to social context troubling. Even as Spoils deconstructs design versus engineering, the book offers little in the way of insight from a number of groups involved in “how we know and make infrastructural landscapes today.” In this case, an expert scholar, representing the interests of an educated and technocratic elite, has laid out a multiplicity of perspectives without addressing working people. Surely they too have acted as co-creators in this so-called “architecture of experience,” right?

Also troubling is Robinson’s tendency to prioritize goals like “reinventing” and “revitalization.” Disaster capitalists already push to rebrand climate change, the upcoming global ecological catastrophe, as a mere problem developers can solve with new innovation and scholars can address with livelier debate. Thus Robinson situates Spoils with a cartographical metaphor: “[T]erra incognita in the middle of a map redrawn for the Anthropocene.” But we know from Jason W. Moore and Raj Patel’s “seven cheap things” that the drive to explore unknown and untouched territory is what led us into this new geological epoch: a period when human activity will have permanently scarred the earth.

These words of caution aside, I walked away from this delightfully optimistic book with hope that humans and nonhumans alike will prove surprisingly resilient to climate catastrophe. Previously, I had only seen Owens Lake as a wasteland every time my family drove up north to visit my great-grandmother’s trailer outside Big Pine. Cecilia and her neighbors would never have imagined government officials they despised debating Owens Lake’s future as a birding destination or a visual resource. Popular subjectivities might start shifting such that we will witness sublime beauty and feel extensive pride in the infrastructure of a Green New Deal. After all, during the last New Deal and well before Marc Reisner, folks practically worshipped dams.

I personally have gone through just such an attitudinal shift at the Los Angeles River, a piece of water infrastructure that may be even more maligned than Owens Lake. This setting for car chases in films and kayak adventures also played host to a participatory dance experience closely mirroring the design intervention from Robinson’s book. Choreographer Jeremy Hahn arranged “The Bridge” in August 2015. A group gathered at the tunnel beneath the late Sixth Street Bridge and approached the river. There, each guest donned a blindfold and paired with a dancer. After guiding us blindly upstream, the dancers removed the blindfolds, and the dead concrete seemed very much alive.

Robinson and Hahn both have endowed us with diverse ways to find value in infrastructure, whether in the middle of this dried lake or on the playa sitting under this channelized river.

¤

Peter Sebastian Chesney is a PhD candidate in history at UCLA.

LARB Contributor

Peter Sebastian Chesney earned his PhD in history from UCLA. He is a historical consultant and a visiting professor at Pepperdine University.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Danger of Amnesia: John Shannon’s “The Taking of the Waters”

Mike Harris reintroduces a three-generation saga novel of the American Left, “The Taking of the Waters” by John Shannon.

Children of the Dammed: On the St. Francis Dam Disaster

The deadliest manmade disaster of 20th-century America and the making of modern Los Angeles.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!