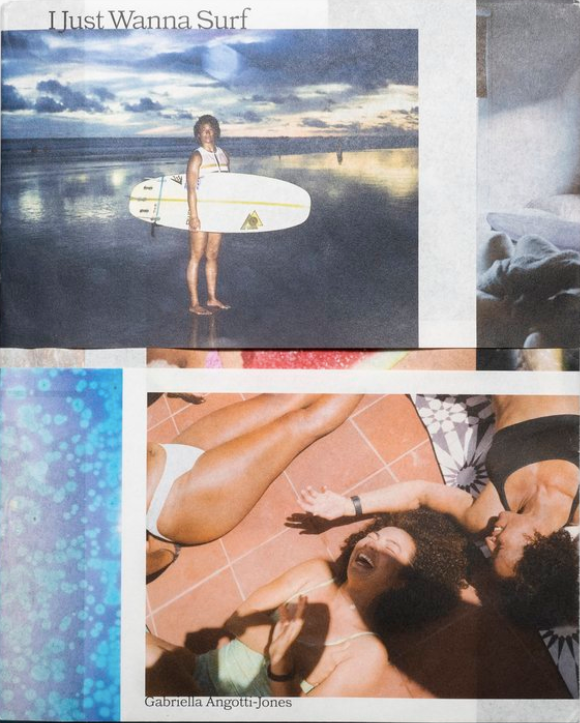

Group-Chat Energy of Delusion: On Gabriella Angotti-Jones’s “I Just Wanna Surf”

Chloe Watlington reviews Gabriella Angotti-Jones’s “I Just Wanna Surf.”

By Chloe WatlingtonMarch 17, 2023

I Just Wanna Surf by Gabriella Angotti-Jones. Mass Books. 144 pages.

THOUGH SHE ONLY intended to take a short vacation, the Belgian New Wave director Agnès Varda visited Los Angeles and stayed over a year—twice. The first time was in 1968, when she wrote and shot Lions Love (… and Lies), in which a producer “thinks it would be funny” to send the New York avant-garde filmmaker Shirley Clarke out to Hollywood to shoot a movie about Los Angeles. And the result is funny—each line, shouted over the next, rings with the social consciousness of the time in a way only Varda could produce: “I hate every form of entertainment, including living.” But it’s also a beautiful landscape film with long, shotgun shots of the city proving Agnes had fallen in love. Varda’s second L.A. movie, Mur Murs (1981), made when she returned a decade later, had the same style of long tracking shots as she visited city mural after city mural, starting in Venice and crossing east to Watts and out to East L.A. Ten years later, the city looks grittier, and the subcultures do too. The hedonism of 1968 had been confronted by other forms of life, and progress had not marched forward in a linear fashion. In the cold open of Mur Murs, Varda’s voiceover observes: “In Los Angeles, you can see angels walking on the Pacific waters, but they are really just blond guys on surfboards.”

“The first jump into the water feels like a baptism,” Gabriella Angotti-Jones writes in her diary-photography-zine, I Just Wanna Surf (October 2022). She means the first jump into the ocean water—a plunge she prefers over a shower—but the metaphor of a baptism also works for her first memory of standing up on a board as a little girl: “I saw everything come together in a mix of sun and birds and people.” From that view, everything made sense, the “vibe of my neighbors and friends.”

Gabriella grew up in Capistrano Beach, a small beach town in Orange County. Capo Beach was developed in the late 1920s by an oil tycoon, Edward Doheny, who came inland from Kern County after playing a major role in the Teapot Dome Scandal—a pre-Watergate tabloid sensation. After his acquittal, Doheny drilled Mexico’s largest oil field, Tampico, as well as the first successful oil field in Los Angeles. His prospecting was supported by bribing the Democratic and Catholic machine, including KKK-backed William Gibbs McAdoo to Archdiocese John Joseph Cantwell, whose Legion of Decency adored Mussolini but protested Hollywood. While Downtown Los Angeles experienced a (brief) real-estate boom and Hollywood collected coin and cultural hegemony, an alliance between Catholic missionary-lobbyists and oilmen like Doheny took over the coastlines. Out west in Capo Beach, Doheny built rows of single-family homes, most likely to secure worker’s housing for his Petroleum Securities Company. While movie stars and bankers flocked to nearby Dana Point, middle-class workers settled into Capo Beach.

By the time Gabriella was growing up in the 2000s, it was one of the last working-class surfer communities in Orange County. But redlining‚ a system of racist laws keeping Black (and Jewish) families out of desirable neighborhoods, was regular practice in Orange County, and so, according to her, “There were no other black families in my immediate neighborhood.” Gabriella, who is mixed-race, experienced a tension between herself and her community. “I didn’t feel black because I was a surfer … I didn’t feel like a surfer because I didn’t fit the stereotype.” And this made surfing hard, because no one actually attends those surf schools to learn: “Surfing is learned from other people.”

When she was nine years old, Gabriella got her first surfboard, a hot pink Liquid Shredder that was much shorter than the board she had learned on. The surfer’s dream is to get off a longboard like a Wavestorm soft top from Costco and onto a shortboard like a Liquid Shredder. The young Gabriella, about to take this transition on, was surveying the waves from the sand when an old white man walked past her on the beach and aroused her confidence. “You gonna ride that thing?” Gabriella noticed her difference suddenly. She was the only girl on the beach about to surf, let alone the only Black person. “I dug my legs into the sand,” she writes. She didn’t surf that day and started going less and less. When she was 11, she stopped altogether, and wouldn’t return for over a decade, when she joined the group chat crew of other Black female surfers. We learn to surf, and not to surf, from other people.

I learned to surf from Michelle, my mother’s ex co-worker, during the summer of 2021. The Great Resignation was peaking, so everyone was quitting their jobs; I had just quit my shitty job, or something like that, and fled to my mother’s house in another working-class seaside town in Northern California, 10 hours north of Capo Beach. The Koch brothers, who purchased one-third of the town from Georgia-Pacific, have left the place in a preserved, unchanging state, suspended in fog, and fenced off as a Superfund site. Michelle had a two-year-old son named Beau. They barely left each other’s side except during the swimming lessons she enrolled him in so that she could take a hot shower at the gym. The drought was so bad that summer that highway traffic signs lined Main Street yelling in all caps: “STAGE 4 DROUGHT CRISIS CONSERVE WATER.” Michelle’s well was dry and there was no water to refill it, so she showered at the gym.

Beau stayed behind on the beach with my mother, Mo. We beat the break of Big River and turned around to face the shore. “He’s probably crying. He never lets me leave him alone,” Michelle said. When we finally caught a glimpse of them, Beau and Mo had their backs to us, silhouettes far from the shore, walking away hand in hand. Michelle had never seen Beau in such comfortable detachment, and I had never seen my own mother as a mother.

In I Just Wanna Surf, a child plays in the sand. A friend bobs her head out of the water in exaltation. A childhood drawing of a surfboard where the board appears like a massive phallus (a boner, frankly) breaking its way out of the sea, followed by a board ripped in half. Gabriella’s friend brings along her little sister, pushing her forward on her skateboard. Her friend’s laughter forces you to confront joy. That seems to be Gabriella’s provocation: “What would it mean to confront joy?” Her admiration for the other surfers in the group chat is an admiration for their refusal of powerlessness.

Two days after Michelle’s surf lesson at Big River, I met Sierra, a mermaid-for-hire doing face paint at a rodeo, who Mo had collaborated with on a protest during the George Floyd uprising. Sierra added me to her group chat for women in the area who surf. A text came through later that day saying that they were meeting up behind the church in Mendocino. I showed up there and nobody seemed to mind a new stranger. We just stripped down and started pressing ourselves into our wetsuits at the tailgates of our trucks, vans, Wranglers. The women work on farms, at restaurants, in grocery stores, around town. They are renters, boarders of the redwood forest. The group chat surfers never shiver when the sun goes down. They catch bigger waves than they are comfortable with. Under the postwork setting sun of the already foggy Mendocino sky, they cross the stormy break where Big River and the Pacific Ocean currents meet, one current coming down from the hills and the other coming towards the shore from wherever it is, way out there, that the water begins.

At night, back in Mo’s neighborhood, I went to the skate park, which was filled with skateboarders in their mid-thirties. Once we had seen each other around a few times, we would chat a bit. They were living with their parents, too, transitioning between jobs, certification programs, and heartbreaks, and—even though they have college degrees—the careers they imagined would be waiting for them after graduation weren’t there.

I first read about this moving-home phenomenon in a 2019 book called Not Working: Where Have All the Good Jobs Gone? In it, David G. Blanchflower compared the Great Recession to the Great Depression as two nearly equivalent events impacting the labor market and triggering social catastrophes, a catastrophe like, say, an entire generation being unable to afford the most basic cost of living: rent. At the beginning of the pandemic, Pew Research released a report about the rapid spike in intergenerational households that placed less blame on the labor market, instead claiming that people were leaving cities out of fear. Most economic reports have gotten away with such excuses in the last few years. But for the quarter of twenty- and thirtysomethings who live in multigenerational households, economic reasons, not confinement measures and contagion, are why they double and triple up on apartments. Meanwhile, the average family size shrinks.

In her book’s dark third act, Gabriella tells a story of barely making it through a night of suicidal ideation preceded by a blurry, dark-blue photo of her friend’s face rising out from under water. The friend’s mouth is slightly open and her eyes closed. A moment of rapture. A transport of the spirit from under to over the surface.

On the next page, she texts her group chat that she wants to kill herself. The chat, as if the chorus in Antigone, calmly, without direct comment on the action, reminds her that there is another fate:

“Love you G! Excited to see you”

“Love you a tonnnn G <3

Can’t wait to give you a squeeze later.”

“Love you G!!

Can’t wait to give you the biggest hug

<3 <3 <3”

The summer I was learning to surf, there was an unusually large fleet of California brown pelicans that roamed as a hunting party, cliff to cliff, from the north side of Fort Bragg in the morning to Mendocino at night. Pelicans are social creatures, traveling in pods called a pouch or a scoop. Everyone in town was talking about these pelicans. Mo’s cold-plunge swimmers group, the woodworkers around the campfire, and the man behind the counter at the butcher shop—everyone agreed: this was an unusually large pouch of pelicans. Mo and I would sit on the cliffs at sunset to watch how quickly they would spring back up from the water after hundred-foot-long free dives off the cliffs. Mo later found out that pelicans are buoyant from a system of air sacs under their skin that gives them a lightness able to battle water. The sacs inflate as they hit the water. Pelicans are unsinkable.

As I was writing this piece, an atmospheric river transported moisture—unusually heavy rains and snow—across the West Coast. Atmospheric rivers account for about half of California’s rainfall annually, but because of climate change they are one of the many “whiplash events” wreaking havoc as drought-hardened land is bombarded with 10-foot waves and subsequent flooding. The governor called a state of emergency and appeared on TV to announce that the atmospheric river was more dangerous than fire season. A confession that precludes admitting that, well, you know, it’s all connected. Some 400,000 residents were without power; another 3,000 were forced to evacuate, people fleeing again from areas where they had previously been forced away due to forest fires. By the time the river had run its course, a dozen people were dead.

I haven’t surfed since leaving Mo’s house up north. My truck broke down. I got a job. I still get the texts and long to show up behind the church on a cold afternoon. In the meantime, swells up to 30 feet crashed the shores. Someone texted the group chat up north, “Big River anyone?” Silence. Then, “Too soon …” I had an instinct about what Gabriella was up to. She emailed me back right away: “I’ve been preparing to be in bigger surf, and then have been absolutely annihilated, it precipitated a small depressive episode and a brief moment where I wanted to move out of LA??? Lmaooo.” The storm had fallen on the anniversary of a previous year’s heartbreak, and so when she risked it for that baptism, she said, “[I got] my ass absolutely handled in big surf, like everything I’ve been trying to process is physically hurting me.” The rain let up for a few days, but still hasn’t stopped.

Agnès Varda was a photographer by trade, introduced to film by her husband, Jacques Demy. She would shoot her frames and photos like Gabriella, whose photographs of surfers resist creative direction. Bodies fill the frame and fall out of it: groups in recline like a zoomed-in Cézanne’s The Bathers, hands, feets, wax wrappers, open mouths underwater, an armpit, Gatorade, grapes. Light heats the page. Jump cuts between the serious and the unserious, page by page. Surfers come up for air. Float. Sprawl. The surfers are in no rush. Gabriella closes the book with the lines, “I don’t know where grief is yet.” Landscapes change; the people in them change; their habits around home, family, and self change; a new form of person emerges; and the environment, no matter how alienated we are from it, impacts that form.

Gabriella’s diary and photographs form another record of the falling apart of the bildungsroman, the moral growth of the protagonist in a nonlinear, unfinished fashion—skating back into our parent’s house, into forced communal living, or, in Gabriella’s case, back into the thing we were meant to be doing all along, but from which we were deterred by old white men.

In April 1878, Tolstoy wrote to a friend who was suffering from writer’s block:

I know this feeling very well—even now, I have been experiencing it lately: everything seems ready for writing—for fulfilling my earthly duty, what’s missing is the urge to believe in myself, the belief in the importance of my task, I’m lacking the energy of delusion; an earthly, spontaneous energy that’s impossible to invent. And it’s impossible to begin without it.

Victor Shklovsky, who names his “book on plot,” Energy of Delusion, after this advice, understands Tolstoy to be saying that one must find and channel, “the uncontrolled powers of nature, which erupt in various and unpredictable ways, creating the chaos that we call this world.”

Surfing is the energy of a search. Nothing but a sport—the disappearing sensation of standing on water, gone in 15 seconds. A sport where a sliver of aura comes through: “I saw everything come together in a mix of sun and birds and people.” It’s an exoteric practice done completely alone with other people, out on the ocean, one of the most limitless places we can physically escape to, the heart of the chaos of nature. With both writing in a diary and surfing, one has to know the chaos of nature, find its specific pull, the energy of the search, and in the brief moment you do, there’s a sudden fulfillment of spirit grand enough to replace god; you become, metaphysically speaking, the blond guy walking on Pacific waters. You replace the things people tell you about yourself with powerful things; the energy of delusion takes over and you become buoyant. We are designed, like pelicans, to be able to confront the beach, but we have forgotten how to find our lightness, our realities louder than our delusions. And anyway, most of the times you spot a good wave coming, it passes under you, no crest, just a rolling swerve and you are alone again in the still water waiting. Or you get your ass absolutely handled in big surf.

¤

LARB Contributor

Chloe Watlington is the former managing editor of Los Angeles Review of Books. Her writing can be found there and elsewhere.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Sometimes I Am What I Really Am: On Mark Alice Durant’s “Maya Deren”

Emma Kemp reviews Mark Alice Durant’s new biography of the enigmatic experimental filmmaker: “Maya Deren: Choreographed for Camera.”

The Water’s Edge: On Laura Aguilar’s Photography

Rosa Boshier González on Laura Aguilar’s Los Angeles from The LARB Quarterly, no. 36: “Are you content?”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!