Gangsters of the San Fernando Valley

A contractor’s hit job goes way off the rails in Chip Jacobs’s new true crime book, “The Darkest Glare.”

By Chase FuryJune 12, 2021

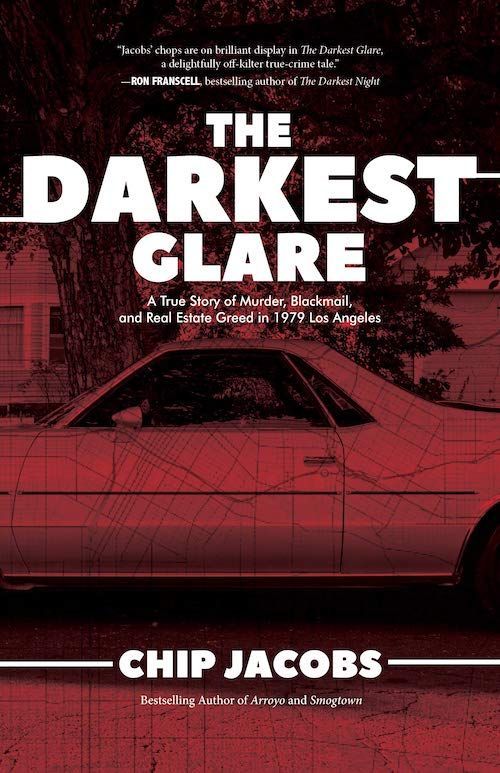

The Darkest Glare: A True Story of Murder, Blackmail, and Real Estate Greed in 1979 Los Angeles by Chip Jacobs. Rare Bird Books. 336 pages.

I ONCE HOUSESAT for a prosecutor. Easy money, I thought. But at 1:00 a.m. on a Tuesday, I heard what sounded like the whimper of a wounded animal. I gripped a bedside lamp to use as a club and went to investigate. The French doors to the backyard had been smashed out.

The cops arrived too late to do any good, but it wasn’t the first time they’d been called to this house. I learned later that some people he had prosecuted occasionally paid him a visit after being released to express their displeasure. The feeling of someone lurking outside my home has lingered for six years since and turned into a gentle hum in my psyche.

But the visceral paranoia hadn’t returned until I read Chip Jacobs’s latest piece of gripping noir nonfiction, The Darkest Glare: A True Story of Murder, Blackmail, and Real Estate Greed in 1979 Los Angeles. Jacobs tells the true tale of three men’s pursuit to create a home-space planning empire in 1970s Los Angeles — a pursuit that sent them down a path of subversion, intimidation, and coercion and that ultimately resulted in a murder-for-hire plot against a businessman named Richard Kasparov.

For Kasparov and his business partner, Jerry Schneiderman, the Southern California real estate economy was a pig in a poke: a dense residential market flush with soaring home values in the wake of tax-slashing Proposition 13. All those homebuyers would need help arranging their new homes. By allowing their space-design clientele to hire their suite-building and furniture-service subsidiaries, they created a one-stop shop that maximized efficiencies in the decision-making process, which they called CM-2. As in, Construction Management, Too.

The company took on considerable debt. Both Kasparov and Schneiderman knew this plan couldn’t sustain itself unless they had a foreman to oversee the operation. They needed someone who was experienced, had connections to vendors for building material, and could share the debt with them.

Enter independent contractor Howard Landis Garrett Jr., “a grizzled, seen-it-all journeyman who referred to the suits in charge as ‘chief’ and [opponents] as ‘clowns.’” Kasparov saw him as their golden ticket and ignored his checkered past. He possessed a California general contractor’s license, which the company needed to comply with state regulations. Using his silver tongue and charming presence, Kasparov convinced Garrett to open his credit line to their company. “Approaching a bank for a measly $3,000 a month […] could elicit doubts about their managerial competence,” Jacobs writes. “Transferring funds from Space Matters could also lead into murky waters because ‘comingling’ accounts invited tax headaches.” Garrett begrudgingly agreed. But when he signed that dotted line to join CM-2, neither Kasparov nor Schneiderman knew they had become indebted to a madman.

The company grew exponentially, as did the debt. There had been no profits, only the promise of great fortune around the corner. Garrett’s credit line had been maxed out, and he was expecting repayment in full. Kasparov gave his roundabout explanation as to why they couldn’t pay, but Garrett wasn’t having it. He wouldn’t play the fool and let some flimflam man take him for a ride.

Lies and corruption festered. When the partners finally discovered that Kasparov had been extorting CM-2 by writing himself checks from the company, Schneiderman decided to end the partnership. It was only then that Kasparov and Schneiderman

peered out at their own circumstances, in a no man’s land between their fractured partnership and fresh beginnings for themselves, [that] they only seized upon the glare reflecting their own troubles, neglecting to be on the lookout for scaly things sneaking toward them.

Garrett is the inept villain you might find in a cartoon, a callous operator that recruits a team of lowlife drug-addicted killers to carry out the assassination of Kasparov and Schneiderman. Garrett needed to insulate himself from the murder, as his motivation was quite clear, so he recruited a fall man for the job. When a friend’s wife asked him for $3,000 to bail her husband out of jail for Christmas, Garrett saw an opportunity: “every favor […] consigns the giver clout,” and Garrett could now weaponize his good deed against his friend, Robert, to carry out the murder for him.

But one night while Howard Garrett slept, Robert “snuck off in Howard’s El Camino on an impromptu trip to score drugs. Before he reached his dealer, unfortunately, he plowed Howard’s pride and joy into another vehicle and ditched the car.”

During the second attempt, Garrett left Robert with meticulous instructions before taking off to Nevada with his wife for a Valentine’s getaway. He waited by the phone to hear that the job had been done. But the call never came. When the phone did finally ring, it was Robert to explain why he couldn’t make it to Kasparov’s house. He had attempted to make a sawed-off shotgun only to have the gun “accidently discharge with an air-bursting crackle” and send metal shards into his eyes. Robert, wanting out from this harebrained operation, passed off the job to a drug dealer named Johnny. From here it snowballed. More criminals were brought into the fold, meaning more loose ends to tie up. When heroin-addicted criminals recruit other heroin-addicted criminals to carry out a crime, the result isn’t ideal.

These brigands are what make the book such a delicious treat. Garrett believes he’s taking advantage of fools and is constantly surprised when they mess up. He can’t express his fuming anger in public because he still needs the hit to be carried out without him. It’s like some macabre version of a Three Stooges act or a Looney Tunes episode. Garrett cycles through different hit men, then eventually chaperones his chosen goons to carry out the assassination. He practically holds their hands as they do the dirty work for him.

The book takes many detours. The narrative follows Schneiderman, then Kasparov, then Garrett, then Robert, then every other character that is briefly mentioned, before dancing its way back to Kasparov and Schneiderman. It’s a large ensemble piece that feels like any Robert Altman film, in which everyone is their own protagonist, and there are no small players. Everyone’s story has a backhoe full of detail.

This world is a familiar one to Chip Jacobs. He explored the same territory in 2012 with The Ascension of Jerry: Murder, Hitmen, and the Making of L.A. Muckraker Jerry Schneiderman. New information has come to light, and in this fresh approach he employs literary devices to explore the inner thoughts of everyone involved. There’s a clear influence of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (1965–’66) as he blends copious research and imagined conversations into each scene.

This approach is not a complete success. Characters sometimes arrive at conclusions that don’t feel justified. The recreated dialogue can make their arcs feel constructed rather than naturally unfolding. The multiple perspectives can be dizzying. But if you have the attention for detail and can track the multiple story lines, then this book is quite an entertaining read. The characters are put through hell and back, with only a few fortunate enough to walk away unscathed. After reading The Darkest Glare, you’ll be looking over your shoulder, wondering if there’s a figure lurking outside your window.

¤

LARB Contributor

Chase Fury is a writer in Los Angeles.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Accidental True Crime Writer

How a chance event sent me into a dark world.

Those Were the Days

A new book chronicles the pathbreaking film, music, and television of 1974.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!