Fury Born from Helplessness: On Leopoldo Gout’s “Piñata”

Matthew James Seidel reviews Leopoldo Gout’s “Piñata.”

By Matthew James SeidelMay 27, 2023

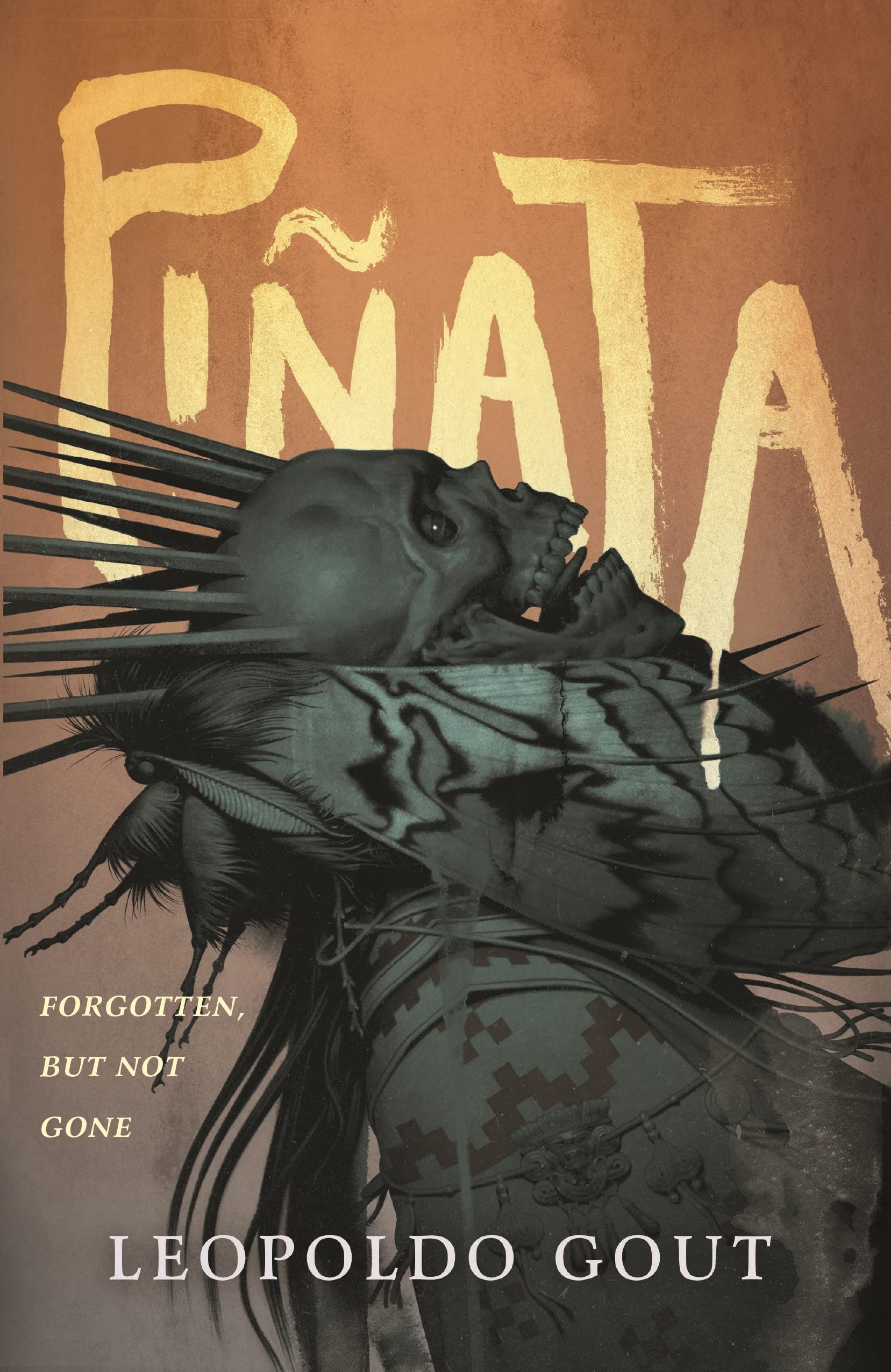

Piñata by Leopoldo Gout. Tor Nightfire. 304 pages.

IT’S TEMPTING to read Piñata—the impressive new horror novel from Mexican visual artist, filmmaker, and author Leopoldo Gout—as a straightforward possession story. After all, at its center is an innocent child taken over by vile forces while her family and a handful of spiritual allies fight to expel the demons before it’s too late. But Gout’s novel is about much more than a confrontation between the obviously good and the obviously evil; it is a story concerned with historical trauma and the systemic violence that it spawns. It also encourages us to ask uncomfortable questions. How much are we willing to sympathize with those who have been victimized but are now victimizing others? Is it possible to take moral revenge against systemic violence? Piñata may fundamentally be a mythic horror story about a group of people trying to stop vengeful spirits from destroying the world, but the horror is more often brutally real than fantastical. In fact, Piñata begins with the end of a world—all the more tragic because it actually happened.

The prologue takes us back to the invasion of Mexico by the Spanish conquistadores. We helplessly witness the carnage from the perspective of the conquered. This is clear from the opening lines, where the sound of thunder is compared to “the booming strokes of an immense teponaxtle drum.” What is a teponaxtle drum? I certainly had no idea when I read those lines and I suspect many readers will not have any idea either. But Gout does not linger to define this term or any other unfamiliar words. For readers like myself, this is alienating in the best possible sense—we are invited to see a familiar historical event from a new perspective. Other readers, of course, will know the word and hopefully feel seen by Gout in a way they might not with an author less invested in excavating the voices of those who are frequently overlooked by the recorders of history.

Gout specifically draws our attention to the Nahua people, one of the many civilizations destroyed by conquistadores. In the end, all that is left is an “absolute drowning silence; the silence of graves […] of the broken musical instruments, of the mute poets. The tlatolli and the cuicatl, the poems, stories, and songs that preserved traditions, memory, art, beauty, and magic have all disappeared.” Without the means to carry on their culture, the world of the Nahua truly is coming to an end. The violence is humiliating and unrelenting, as Spanish friars force young Nahua children to take part in the destruction of the very objects that embody their culture’s deepest beliefs. Afterwards, the Christian oppressor most responsible for tormenting the Nahua endures a painful, surreal death. The prologue, then, gives us a preview of both the historically rooted violence and mythical horror at the book’s core.

The threat of realistic violence Gout builds into the novel extends to the present. The first part of Piñata takes place in Tulancingo, a city in the Mexican state of Hidalgo, where architect Carmen Sánchez has been sent to oversee the renovation of an ancient abbey. Circumstances force her to bring her two daughters, 11-year-old Luna and 16-year-old Izel. Luna absorbs as much information as she can about both Mexican history and the Indigenous cultures that predate the conquest. Izel, meanwhile, focuses on texting her friends. Carmen is eager to introduce both daughters to the country but is also aware of the dangers all around them. Early on, Carmen leads Luna and Izel down a street while men catcall them. Carmen tells the girls to ignore the men, but she keeps “everyone around them in her peripheral vision.” Her paranoia is heightened by the countless posters with missing girls’ faces that bombard them from every direction. Throughout Piñata, Gout draws attention to the countless femicides that continue to plague Mexico today; he does so in a way that recalls the grisly fourth section of Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 (2004), which goes into excruciating detail about what happened to the kinds of girls whose faces now surround Carmen, Luna, and Izel. Another character later scans the front pages of newspapers “showcasing mutilated bodies, gunshot and knife-wound victims,” bemoaning the fact that the “grotesque had lost its ability to shock, to move, to anger. Women, so many murdered women, up to ten in one day across the country, people said. It seemed more and more unbelievable, the brutality of their murders.”

The palpable atmosphere of dread comes not only through reminders of the femicides. In the final section of the novel, when Yoltzi and her friend Quauhtli decide to leave Mexico to save Luna, they confront the many dangers migrants face in their journey to the United States. These include drug traffickers, sadistic border patrol agents, and roving gangs that are willing to kill or enslave anyone they can.

Not long after the Sánchez family arrives in Mexico, there are signs that something strange is happening: an old woman with a monstrous face keeps watch over the family; buried relics irresistibly call out to Luna for reasons she cannot explain; and, worst of all, terrifying visions hint at the chaos to come. While Carmen and her daughters remain ignorant of the dangers awaiting them, Yoltzi, a descendant of the Nahua, is not. Yoltzi has gifts that even she struggles to understand, but they allow her to see the spirits of those butchered by the conquistadores, phantoms that believe the spiritually sensitive Luna may provide the perfect vehicle to enter the world and exact revenge. Yoltzi keeps watch over the family in secret, at one point hiding behind a newspaper stand to avoid detection. It is here that she dwells on the scale of the murders plaguing Mexico. But interestingly, she thinks to herself:

This much hate had to come from somewhere. All that resentment, animosity, and frustration the country and the world had been hoarding for so long, it had to come from somewhere crueler, more sinister, more ancient—a sweeping force that planted the desire to leave everyone motherless, sisterless, daughterless. A homicidal force set on ending women altogether.

For a character as steeped in Nahua religious beliefs as Yoltzi, this speculation is not surprising. But it does raise a question—what does it mean to assign a spiritual or demonic motive to human violence? Does this exculpate the perpetrators? Or does it speak to a primal, psychological rot in human society?

More complicated yet is the question of how we are to see the vengeful spirits of the slain Nahua. If there is a villain in Piñata, it is clearly them—they are the ones whose possess Luna and slowly tear her family’s world apart before seizing their chance to try and destroy the entire world. But these are the spirits of the same people who were massacred by the Spanish in the prologue. They were clearly the victims then, so their lust for vengeance is understandable. Yet the people who hurt them are long dead. Their victims are the descendants of the conquistadores or, much more likely, descendants of people who either came to Mexico and the United States later or are not connected to them in any genetic sense. The only undeniable connection is that the people the Nahua now seek to punish are the inheritors and beneficiaries of the invaders—they are living in the countries built atop Indigenous peoples. Is that alone enough to justify their actions?

It is worth comparing Gout’s treatment of the colonized-colonizer relationship with Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s Mexican Gothic (2020). There are many similarities between these two horror stories, but the villains in Moreno-Garcia’s novel are the descendants of colonizers (well, sort of—you’ll have to read it) who abused the Indigenous population. In Piñata, the Indigenous people, or their spirits at least, are the villains. In fact, one of the people who tries to help Carmen’s family is a Catholic priest as determined to destroy the Luna-possessing spirits as the Catholics in the prologue were to wipe out the Nahua entirely.

As a reader, I felt quite conflicted about this recapitulation throughout most of the novel, but Gout smartly anticipates this tension and addresses it directly in a dialogue between the spirits and Yoltzi. The spirits castigate her as a traitorous “descendant [of those Nahua] who would rather rot in the afterlife forever, your memory and culture trampled on, than get revenge.” Yoltzi responds by “looking down at the face of her people’s apocalypse, a real manifestation of a culture lost and buried by violence and conquest.” In doing so, she understands “the unconscious terror her people had felt centuries ago. The pain of erasure, the fury born from helplessness, and the grief of so much lost had twisted this powerful goddess, this woman warrior, into a demon of revenge.”

Yoltzi argues to the others that “we have to live among the living […] History moves with a swift cruelty. Fighting it is impossible. The spirits of the dead unable to leave their grudges behind poison the air for the living. Luckily many of my ancestors understood that more than others.” But does this philosophy risk allowing systemic violence to continue? Does “fury born from helplessness” always lead to evil? While there are no easy answers, by making both his villains and at least one hero part of the same lost society, Gout encourages readers to think about what should be done to rectify the multiple historical traumas that continue to afflict the world today.

Piñata is a fast-paced horror story that draws on history to give it a depth and sense of scale that similar stories often lack. And by incorporating real-world violence into the plot, Gout elevates the novel into something much more than it needs to be to succeed as a possession story. As much as readers might find comfort in the conclusion of Piñata, they will still be left haunted by the knowledge that so much of the violence these characters face exists everywhere. And confronting it means confronting the worst parts of our history, our society, and ourselves.

¤

Matthew James Seidel is a musician and writer currently based in Florence, Italy.

LARB Contributor

Matthew James Seidel is a musician and writer currently based in Rochester, NY. His essays and reviews have been featured in the Los Angeles Review of Books, The Millions, Jacobin, Protean Magazine, Liberated Texts, Ebb Magazine, Current Affairs, and AlterNet.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Refuge and Resistance: On Sophie K. Rosa’s “Radical Intimacy”

Matthew James Seidel reviews Sophie K. Rosa’s “Radical Intimacy.”

The Daughter Displaces the Island: On Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s “The Daughter of Doctor Moreau”

D. Harlan Wilson reviews Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s “The Daughter of Doctor Moreau.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!