The Daughter Displaces the Island: On Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s “The Daughter of Doctor Moreau”

D. Harlan Wilson reviews Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s “The Daughter of Doctor Moreau.”

By D. Harlan WilsonMarch 11, 2023

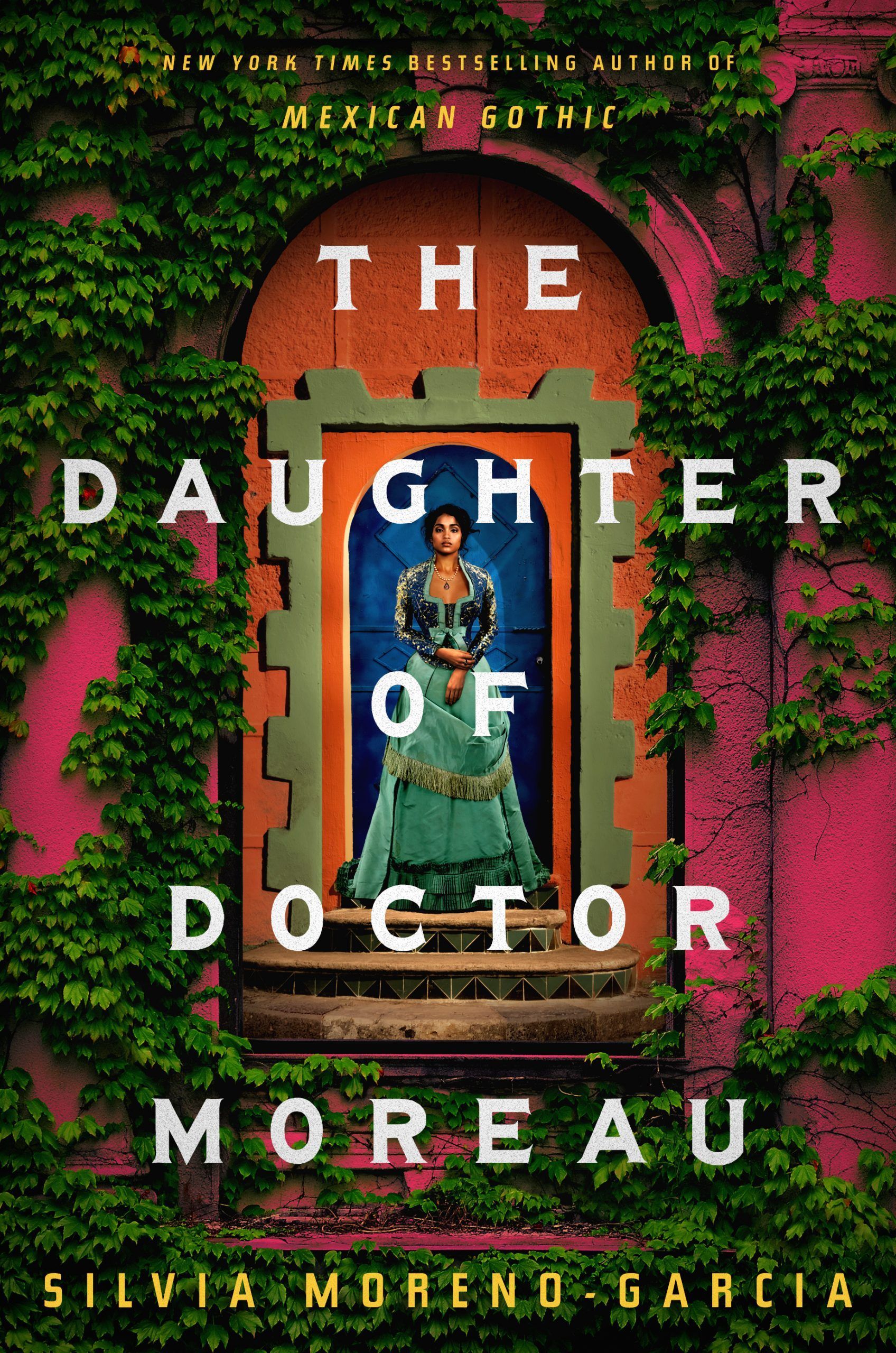

The Daughter of Doctor Moreau by Silvia Moreno-Garcia. Del Rey. 320 pages.

THE TITLE of Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s Mexican Gothic (2020) denotes its story as well as its literary subgenre. Set in the Mexican countryside, this feminist horror novel depicts a woman’s oneiric, dread-inducing experience in a haunted mansion that siphons Edgar Allan Poe’s iconic gothic tale “The Fall of the House of Usher.” Like Poe, Moreno-Garcia features an enigmatic lord of the manor, bad omens, hidden family secrets, and a murder mystery. She must have liked the idea of using another author’s work as a speculative template. In her latest novel, The Daughter of Doctor Moreau (2022), she retells what may be H. G. Wells’s darkest scientific romance, The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896).

Authors have used the technique of riffing on (or altogether reworking) old storylines for centuries. In the 21st century, that usage crossed a threshold into unabashed exploitation with novels like Seth Grahame-Smith’s Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (2009), a parody of the Jane Austen classic that deploys some 85 percent of its prose verbatim. Legally, there’s nothing wrong with this sort of liberty-taking, if that’s what it is—Austen died over 100 years ago and the text of Pride and Prejudice has long been in the public domain—but there is considerable debate as to what constitutes a reimagining or a rip-off, let alone exploitation. Did Melville exploit cetological literature in Moby-Dick (1851)? A case could be made against hundreds of novels and stories, but nobody cares enough to make too big of a stink. Adapted into a graphic novel in 2010 and a movie in 2017, the bestselling Pride and Prejudice and Zombies appears to have been more liked than disliked by readers.

By no means does Moreno-Garcia follow Grahame-Smith’s lead in The Daughter of Doctor Moreau. She doesn’t repossess any of Wells’s text, and, to a large degree, she tells a different story. She retains the monomaniacal mad scientist Moreau and his exiled, alcoholic assistant Montgomery, giving the latter a surname (Laughton) and making him into the mayordomo of the Yaxaktun ranch on the Yucatán Peninsula where Moreau conducts his experiments. She gets rid of the British narrator of The Island of Doctor Moreau, Edward Prendick, who is more of an outsider point of view than a person. The youthful, “healthily bronzed” Carlota replaces the careworn, thirtysomething Prendick. The name means “freedom” and belonged to an empress “who reigned in Mexico for a few scant years.” Carlota is a bastard girl born to Moreau and an Indigenous lover in the mid-19th century after his first wife and baby daughter died from fever. Throughout the novel’s 31 chapters, which are divided into three parts by date (between 1871 and 1877), the perspective shifts back and forth between Carlota and Montgomery. There is sexual tension between them, but for the most part, Montgomery functions like another father figure to her, and whereas Moreno-Garcia uses third-person narration, we see this world through their constantly oscillating eyes.

At Yaxaktun, Moreau performs experiments on animals to create hybrids, just as he did on Wells’s island. Also, like Wells’s vivisected “Beast Folk,” Moreno-Garcia’s hybrids perceive Moreau as a deity and fear pain above all. He even plays preacher and holds Saturday church services, “reading from the leather-bound Bible with the red cover.” He deploys religion to displace the hybrids’ traumas and contends that his work will lead to cures for multiple illnesses. The aberrant hybrids are “born with strange and odd ailments that could claim them in painful ways. [They] suffered for the sake of humanity.” Moreau portrays their pain as a gift: “Pain must be endured, for without it there’d be no sweetness.” He strikes this chord with regularity to keep the hybrids at bay. I’m reminded here of Katherine Dunn’s Geek Love (1989). In Dunn’s novel, a husband and wife breed their own freak show with radiation and gene-altering drugs; in effect, their children suffer from physical and psychological infirmities thanks to the antagonism of their unhinged parents. Moreno-Garcia’s ability to evoke sympathy and empathy in readers is much closer to Geek Love than to The Island of Doctor Moreau, which initially seemed to me like a peculiar choice for extrapolation into a Mexican gothic context. I soon realized that The Daughter of Doctor Moreau dismantles Wells’s inherent patriarchy and affect.

The Englishness of H. G. Wells overpowers his scientific romances, as does the colonialist impulse that typifies his era. Rhetorically and socially, his characters abide by a certain code of internalized aggression and sublimated performativity—stout fellow!—while power invariably belongs to men. Nobody can discount Wells’s contribution to SF and literature; he’s probably still the most important SF author that ever lived. However, looking backward at Wells becomes increasingly difficult given the white male ethos that utterly dominates his oeuvre. Along with The Island of Doctor Moreau, novels like The Time Machine (1895), The Invisible Man (1897), The War of the Worlds (1898), When the Sleeper Wakes (1899), and The First Men in the Moon (1901) see him project Englishness onto the entire world, treating it as a matter of (global) course. The effect is a colonization of (narrative) worlds with an English affect. Moreno-Garcia deterritorializes this dynamic and what it signifies in terms of the social and cultural order.

The Daughter of Doctor Moreau thematizes patriarchy most conspicuously in the subplot that involves Moreau’s patron and sponsor, Hernando Lizalde, and his son Eduardo, an entitled coxcomb to whom Moreau wants to marry off Carlota in order to secure more funding and supplies from the young man’s father. At first, the naive Carlota has great affection for Eduardo, but over time his patriarchal worldview comes to bear as she develops self-awareness. By the end of the novel, Carlota refashions her own worldview to grapple with the way that Eduardo sees her as “merely a doll to be carried around. Life with him would be, as he said, simple and good as long as she agreed with everything he said. And then, if she didn’t, his fingers would dig too tightly into her skin, his words would scrape low and dangerous against her ear.”

Armed with this new perspective, she resolves to break away from Eduardo after Moreau dies of heart failure. Entitled, power-hungry little men don’t take kindly to rejection. Eduardo tries to claim her by force. Carlota kills him and steps into the role of her father, not as a tormenter but as a savior. Rather than extending her father’s dystopian “legacy of misery and pain,” she plans to take the hybrids away from Yaxaktun and establish a more utopian community where “[t]hey’d be safe and the world would be good, and the house would be filled with the laughter of her family and the people she cherished most. […] The heaven they would build would be theirs and not built by a man. The heaven they’d build would be true.”

The three men in Carlota’s life—Eduardo, Moreau, and Montgomery—all impact her psyche and growth in unique ways. The development of Carlota’s relationship with them unfolds alongside subplots concerning her connection with the hybrids (e.g., Lupe, whom Moreau created to be her childhood playmate) as well as mounting rumors of a Yaxaktun takeover by General Juan Cumux, a Mayan rebel, would-be usurper, and leader of guerrilla “Indians.” Carlota’s awakening culminates in the murder of Eduardo, although she’s only able to overpower him because of her father’s treatments. Afflicted by a kind of Stockholm syndrome—“the joy that kills,” Kate Chopin might call it—she learns from Moreau on his deathbed that her mother was a prostitute whom he paid to impregnate with his own gemmules (presumably through in vitro fertilization) before adding the gemmules of jaguar. “I made you, like I made the other hybrids,” he explains. “You are an impossibility, practically a creature from myth. A sphynx, my love.” Moreau gives her regular injections throughout her life to mitigate a rare blood condition, but after he dies and Carlota stops receiving injections, the mythical creature inside her comes out, and she mauls Eduardo. “She ceased to be Carlota and became fear, became anger, became death, became fur and fang and fury. She slashed and she bit and she tore apart.” Thus her awakening encompasses a revelation of (self-)perception as well as a physical transformation into animal form, which is also a movement from the culture of her father’s estate to a state of primal nature. This movement is almost a prerequisite for feminist SF, with culture (especially technological violence) being coded as male and nature coded as female. Sometimes authors lay it on too thick and become overly didactic; Moreno-Garcia finds a good balance between storytelling and social commentary.

Another coding in the novel has to do with class, particularly the way hybrids are perceived and treated like proles. In addition to exploiting them as lab rats, Moreau has designs to sell them off as laborers. “She knew her father made the hybrids to please Hernando Lizalde and that ultimately he’d want them in his haciendas,” she eventually realizes, “yet she never thought they’d abandon the confines of Yaxaktun. Her father’s research was not where it needed to be to allow that, and besides, she had lulled herself into a sense of safety.” Carlota’s maturation hinges on the molting of this “sense of safety” as she comes to terms with who she is and what she wants for herself and her loved ones. Bred by Moreau in the belly of pigs, the hybrids signify the culture-nature binary that she must straddle and implode in order to find herself. Montgomery becomes a mentor to her on her journey; in the chapters that he headlines, we learn his backstory, mostly a chronicle of loss and grief. He’s broken and full of bile when we first meet him, and even though he never really heals, we see him evolve into a better man (i.e., a less aggressive and entitled patriarch). I don’t know if Moreno-Garcia intended it, but his first name is a terrific irony: the gravely serious Montgomery does not make a habit of laughing, and he certainly doesn’t “laugh” a “ton.”

Montgomery is a drunk in The Island of Doctor Moreau, which foregrounds similar issues and motifs. Moreno-Garcia uses the same thematic toolkit but renders something else. Wells’s novel foregrounds theme over character; more than anything, perhaps, he puts morality in question and frets over the dark potential of advanced technology, as he does in all of his scientific romances. The Daughter of Doctor Moreau does the opposite. Moreno-Garcia has written a case study about dominant and marginalized peoples (and nonpeoples) under the auspices of patriarchal power, aggression, and abuse. The daughter displaces the island and embodies the landscape of mysteries to be unlocked, psychologically and corporeally. We don’t know if Carlota will fulfill her desires to relocate the hybrids and become their new, nicer god. She doesn’t want to be a god to them, but they have all been programmed by religion their whole lives, and there’s no escaping the monster inscribed by the law of our fathers. Still, while Carlota remains “religious,” she adopts a more pantheistic view that venerates “the God that lived in every stone and every flower and every beast of the jungle” instead of some fearsome, vengeful divinity. The references to the natural world here point to how her ideology comes to align with her femininity and her embodiment of “Mother Nature” itself.

The gothic essences in The Daughter of Doctor Moreau culminate in Carlota’s transformation into a feral killing machine and, thereafter, a would-be beneficent matron of the wild. In capable, at times beautiful prose, Moreno-Garcia makes a sound feminist critique that decodes the patriarchal protocols of its source material and 19th-century attitudes in general. This work of soft, gothic, literary SF isn’t so much a scientific romance as an experiment in (recycled) storytelling through the vehicle of concerted character studies.

¤

LARB Contributor

D. Harlan Wilson is a professor of English at Wright State University–Lake Campus, the reviews editor of Extrapolation, and the editor-in-chief of Anti-Oedipus Press. He is the author of over 30 books of fiction and nonfiction, including scholarly monographs on the life and work of J. G. Ballard (University of Illinois Press), Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report (Auteur Publishing), and Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination (Palgrave Macmillan). Visit Wilson online at dharlanwilson.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“Writing Was an Act of Survival”: A Conversation with Reyna Grande

The author discusses her latest novel, “A Ballad of Love and Glory,” a sweeping historical drama set during the Mexican-American War.

A Revisionist Mythos: Frankenstein Versus Cthulhu

New novels by Kim Newman and Michael Shea illustrate the power of popular myth.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!