Fractals of Fractals: on April Ayers Lawson’s “Virgin and Other Stories”

“Virgin and Other Stories,” the debut collection from April Ayers Lawson, masterfully creates the sense that the world is chaos.

By Lindsay HunterNovember 1, 2016

Virgin and Other Stories by April Ayers Lawson. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 192 pages.

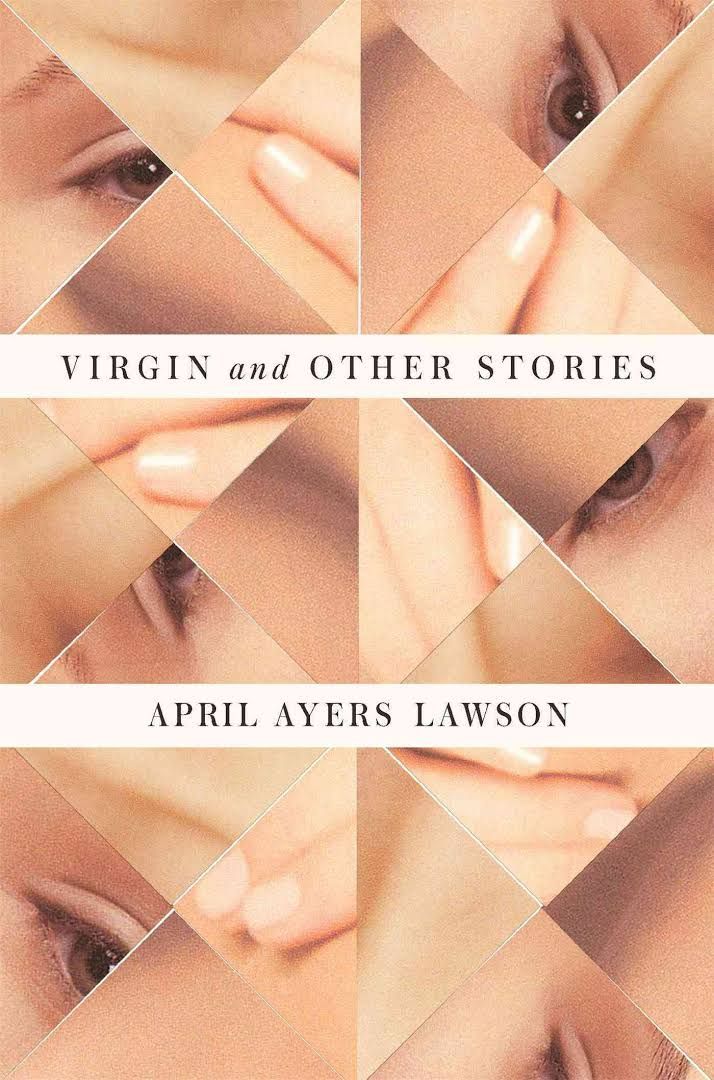

THE COVER of Ayers Lawson’s excellent debut collection, Virgin and Other Stories, is a puzzle, its pieces comprising images of an eye, fingers, and snippets of flesh arranged in different patterns. Look at it this way. Now look at it this way. Is it a woman? A man? Is this arousal, or fear? Lawson’s stories disorient in the same way. They are linked thematically, in details great and small, but they never provide a complete and graspable image. In each of her five tales, Lawson seems to be saying: Have fun assembling this anti-puzzle.

There’s an old writing exercise in which you ask a group of people to write the same story. You provide the basic plot points and some details, and then later read what they’ve separately come up with. The results are usually wildly different, because the writers are different people and the details they notice and deem important are different, and because the characters they write are different and thus the story they tell will be different, and on and on and on. In Virgin and Other Stories, I felt as though I was reading fractals that had fractaled; I got the sense that each story was a piece of a larger object, that there was a storyteller outside each storyteller. Of course, there is the actual storyteller, Lawson herself, who received the 2011 George Plimpton Award for Fiction as well as a 2015 writing fellowship from The Corporation of Yaddo — no slouch of a storyteller — but it feels as though there is another force at play here, some source or being that collects, arranges, reveals, and hides. It is as if the book is not only stories written by Lawson, but a collage made from these stories which ultimately poses to the reader a nearly answerable question. A puzzle in which each reader decides what the ending image will be; each reader gets to be a small god.

Religion appears in every story, along with varying levels of sexual awakening. The first, entitled “Virgin,” begins with a man named Jake noticing a woman’s breasts. Jake’s wife Sheila, a graduate of an evangelical college (as is Lawson) and a woman who “saved herself” for marriage, no longer wants to have sex with Jake. The reason why is complicated and never fully explained. She was molested as a child; she may be having an affair. Both seem like equally plausible reasons for her disinterest in sex with Jake. In long passages, Jake describes the tension in his marriage when it was new. He sees Sheila as secretive and damaged. Is the story about him, or his wife? Is the story about the woman, Rachel, whose breasts he notices? I found myself squinting, rereading, searching. I was bewildered and excited. I had the sense that the story was happening beyond Jake, Sheila, and Rachel. I was looking the wrong way, and if I shifted my eyes quickly enough, there my answer would be.

“Virgin” concludes, gorgeously, with Jake and Rachel alone in a room:

In the soft light and emptiness, the room might have been any room or every room he had ever known, and she had always been in this place that was also herself, waiting. The muted laughter from the party could no longer be heard. Faintly, the music he had not noticed below announced itself through the floor.

In one sense, the story is about want finally laid bare. In another sense, it’s about distraction from that want. The laughter disappears; the music rises. The story ends with the promise of touch — but not actual touch. They are simply two beings in a room that could be any room they’ve ever known. It is not a sad or happy ending; it’s not really an ending at all.

I have a theory about the arrangement of stories in a collection: the first and last, of course, act as bookends — or rather, like inverted parentheses, funnels, one gathering you in and the other ejecting you out the other side. The second story is the one to really pay attention to. If the collection is any good at all, goes my theory, it’s where an important pivot occurs, where readers get a sense of what they’re truly in for. Virgin and Other Stories is a case in point. Its second story, “Three Friends in a Hammock,” is a tangle, purposely disorienting, and it is the true guidepost for the book as a whole. It pivots violently, spilling coffee all over your jeans. It is the shortest story in the collection, and the strangest. It’s a story about a “we,” though it’s told by an “I.” It feels like a long algebra problem — there is a character called “X,” and there are commonalities, like divorce, between the characters, and it seems as if the narrator is trying to work it all out in smudgy pencil etchings on the edge of a crumpled piece of paper. The narrator is perceptive, noticing and noting more, it seems, than the other characters give her credit for: “I knew what it was like to have found out some vital information about the person in the next room that he wouldn’t want you to have, and I also knew what it was like to be the one to whom such information was presented.” It’s purposely oblique, as pure as a middle schooler new to gossip, yet cunning and nearly omniscient. This kind of voice makes for a twisty pretzel of a story; for me, its weirdness continues to echo throughout the book.

“The Way You Must Play Always” intensifies that perplexing sense that the real story is happening outside of the visible frame. Gretchen is a teenager, forced to take piano lessons from a wilted genius named Miss Grant after being caught kissing and petting and et cetera-ing with her cousin. The story could be about Gretchen’s burgeoning sexuality, the power with which it endows her; it is that old tale of a girl-who-yearns-to-be-touched-so-she-can-mistake-it-for-love. But Miss Grant and her odd brother Jeremy complicate that picture — there is something happening in the house beyond Jeremy’s brain tumor, beyond his illness-induced ennui, beyond normal sibling tension. Jeremy whispers, “God, but I love her,” into Gretchen’s hair, leaving us to wonder who the “her” is. Could it be Miss Grant? The story ends with Miss Grant’s other student, Fiona, staring at Gretchen while she cries: “The rain had stopped but ran off from the roof and fell like a clear, shiny curtain before Fiona’s curious face.” Both girls appear to have wet faces as they look at each other. Fiona’s curiosity in the face of Gretchen’s tears is an interesting subversion. We end on an outsider’s reaction; again, we are looking elsewhere for missing pieces of the tale.

In “The Negative Effects of Homeschooling” we meet Conner, a teenage boy indulging and fighting his burgeoning sexual urges (“I had hard-ons ten or twelve times a day”) while also telling the story of his mom’s friendship with Charlene, “a woman who used to be a man.” It’s not entirely clear at first why Conner feels such disgust and anger toward Charlene, but it becomes clear he is jealous of the side of his mother that Charlene brings out. She accepts his mother as a whole person, something Conner is incapable of doing. Lawson so masterfully renders the mind of a teenage boy — myopic, literal — that the source of his rage isn’t revealed until the final scene. His mother, wearing a fur gifted from the now-deceased Charlene, is confronted by an animal rights group. Conner, screaming and crying, shoves one of them to the ground. His mother tries to calm him, and the story concludes with, “‘See, Conner?’ Her eyes caught mine and held them. The wind lifted her hair from her face. ‘I’m okay now. I’m okay.’” The side of his mother to which Charlene had access was foreign to him, a confusion, something that didn’t include him. In the final moments of the story, Conner wants to protect the mother he knows. He is exorcising the fear and alienation Charlene brought into his young life, and his mother sees it. All along, the story has been about what Conner sees, but in these final moments we truly see Conner.

Many of the threads winding their way through the stories converge in “Vulnerability,” the final tale in the collection. Friends in “The Negative Effects of Homeschooling” talk about the Zelda Fitzgerald biography they’re reading; in “Vulnerability” an art dealer and the artist discuss F. Scott Fitzgerald. An Albanian ex-husband appears in “Three Friends in a Hammock,” and an Albanian fiancé in “Vulnerability.” The wife in “Virgin” wears very short skirts and was sexually abused as a child; the same is true for the artist in “Vulnerability.” I’d characterize these echoes as seeds, planted in the first four stories that finally blossom in the fifth. What does Lawson want us to think about these details? That there is meaning in coincidence or similarity? That we are all missing something, that we are all connected in these weird tiny ways? That we are all part of the same giant brain, traveling the same dreamscape?

“Vulnerability” is the collection’s most ambitious story. A married painter travels to New York to meet with an artist she believes she is in love with, as well as with an art dealer who has expressed interest in her work. It is the art dealer she ultimately falls for, though the story ends with a startling, violent sexual encounter that forces the narrator to reflect on the abuse she suffered as a child and how it affected her sexual relationships for her entire life. At the same time, Lawson messes with the whole notion of “storytelling,” switching voice from first to second to third person, and back to first person. At times, she uses language that is purposely clunky, overdone, calling attention to the writing of the story one is reading. The book masterfully creates the sense that the world is chaos, and that in order to really see it you must avert your eyes. Lawson ends on the line, “There is nowhere else to go now. The room fills with light,” leaving the reader with the feeling that the collection’s true author, who has been hovering in the corners of each story, revealing and hiding and reusing, is bowing out, is all done now. She has told the story as best she can and it’s up to the reader to fit the pieces together.

The effect of this, for me, is the realization that ambivalence is highly underrated. Uncertainty means stories live on, their meanings change, they pop up when you least expect it. It means the book is eminently rereadable, because you’ve certainly missed something in your first pass. And it means that the author has created lives that are complex, maddening, baffling, filled with heart and breath and life.

¤

LARB Contributor

Lindsay Hunter is the author of the novel Ugly Girls and the story collections Don't Kiss Me and Daddy's. Her next novel, Eat Only When You're Hungry, will be released in August of 2017. She lives in Chicago with her husband, sons, and dogs.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Look at Your Game, Girl

Emma Cline’s “The Girls” is the coming-of-age story of a 14-year-old girl who falls in with a Manson-like cult just months before a night of brutal...

The Emerging Genre of Slut Lit

The emerging genre of Slut Lit reminds us how women’s bodies have always been a sort of Rorschach test for society’s deeper anxieties about women’s...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!