Extraordinary Hustle: A Profile of Laure Calamy

Eileen G’Sell interviews Laure Calamy, star of the film “Full Time.”

By Eileen G’SellFebruary 6, 2023

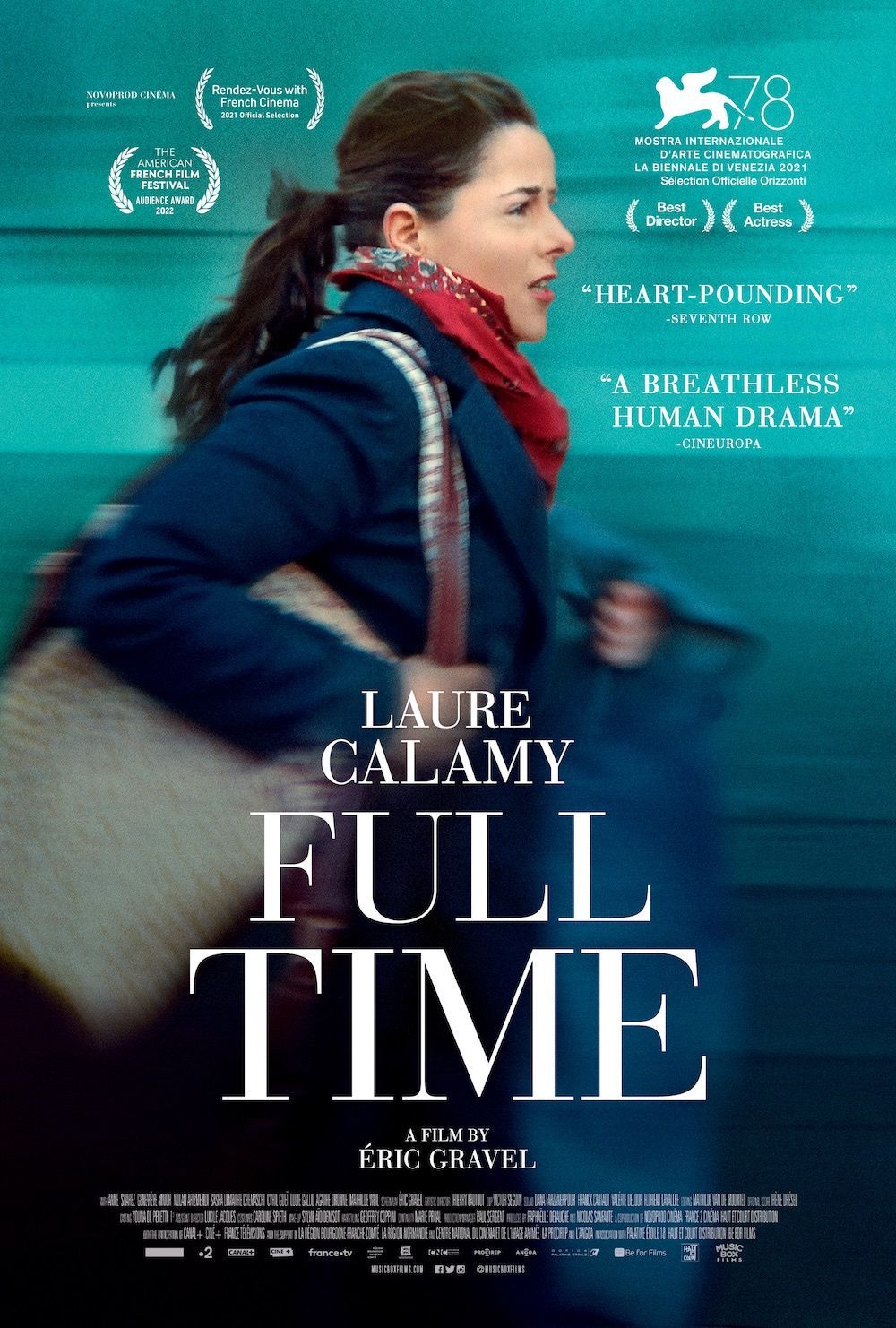

LAURE CALAMY is late. Fifteen minutes late. I’m scheduled to be on my college campus in 40, and duly anxious that I’ll be late too. Making small talk on Zoom with her affable translator, I think about Calamy’s performance as Julie in Full Time, Éric Gravel’s new film about a single mom scrambling to find ways to and from work during a Paris rail strike. Despite bribing cabbies, hitching rides with strangers, and sprinting across town in mid-heel boots, Julie shows up painfully tardy to her maid job at a five-star hotel, and then again when she meets the elderly neighbor who has reluctantly agreed to babysit her kids. When she does arrive, she is breathless, contrite, her ponytail tousled into chestnut waves. Julie’s the kind of person it’s easy to forgive — until, one day, for many characters, it’s just not.

Of course, Laure’s Lateness has nothing to do with anything as dramatic as the periodic shutdown of the second-busiest metro system in Europe; her laptop had issues with the Zoom link. Yet, when she shows up, speaking into her iPhone from a marigold living room lined with bookshelves, she exudes an endearingly frantic vibe not unlike that of her latest role. My students can wait, I think. They rarely come to morning office hours anyway.

After congratulating Calamy for her recent César nomination for Best Actress — France’s greatest film honor, which she won last year for 2022’s My Donkey, My Lover & I (in French, the less awkwardly titled Antoinette in the Cévennes) — I consider her wild shift playing quirky rom-com leading lady to harried mother of two. “I don’t know if it’s the same thing in the United States, but in France, there are a lot of single-parent families,” Calamy explains when we discuss Full Time’s larger themes. “And in most of these families, the single parent is the mother — who then becomes responsible not only for her own survival and her own work, but also for bringing up the children. Julie has this double burden.” As I later find out, the United States and France have about the same percentage of single-mother families — around a quarter of all households with children, 80 percent of which are led by women. An original member of Le Collectif 50/50, a French organization devoted to gender equality in the film industry, Calamy seems eager throughout our exchange to point out the unexceptional nature of Julie’s set of circumstances.

While I can’t make out much of her French on Zoom, her jaunty cadence and volubility remind me more of a beloved art professor than a famous actrice. (To wit: She played a teacher in the donkey movie.) Given that most leading French actresses today are proficient in English, the need for a translator suggests that Calamy, 47, may be fairly new to press coverage outside her home turf.

With her star turn in Full Time, that may very well change. Set to an electronic beat reminiscent of Tom Tykwer’s 1998 Run Lola Run, Full Time trails Calamy through every shot — at times, the camera can barely keep up with her. Never mind that Julie is a middle-aged mom in mid-heel boots, not a twentysomething Berliner in weathered Doc Martens. “They never asked me to slow down,” Calamy recounts, when I laud her speed onscreen. “This is really the normal way that I walk. My walk is very quick — my own rhythm, also. And I wasn’t asked to change it. The way that I run, the way that I walk, all fits with the character.” After a brief pause for the translator, Calamy tacks on a final point to emphasize just how common this supposedly is: “It’s how I am and it’s ordinary. It’s how a lot of ordinary people are. What’s really interesting about this film is that it’s about the life of an ordinary person, but it’s filmed like a thriller.”

“Ordinary” she is surely not. Calamy has long mastered the art of riveting yet relatable characters, gaining widespread acclaim in 2015 in the Netflix/ France Télévisions comedy Call My Agent! as Noémie Leclerc, a secretary at a Paris talent agency who is smitten — and occasionally sleeping — with her boss. With her enormous eyes and petite, curvy frame, Calamy has the look of a character actor, distinctive and humorously expressive. Indeed, the majority of her performances have been in supporting roles in comedic dramas; when I mention her knack for physical comedy, she nods with a “oui.”

In Full Time, Calamy pours that expressive energy into portraying how much Julie’s body goes through each day on precious little sleep. Gravel’s script encourages us to root for her while honestly reflecting the unsavory lengths she will go to in order to get ahead and, simply, get by. In the breakneck days captured onscreen, Julie inadvertently gets a young co-worker fired, throws expletives at a Métro employee, and foists a nonconsensual smooch upon a neighbor repairing her water heater.

“One of the things I liked about the character was her tenacity,” Calamy shares. “She doesn't let anything get by her. She does what she wants to do, even if it’s to the detriment of others. She’s living in the moment. The character benefits from [Gravel’s] very well-written screenplay. But, I think, also part of it is that I was present in that character. When I was on the set, part of me was in Julie too.”

But unlike Marion Cotillard playing a factory worker in the Dardenne brothers’ 2014 Two Days, One Night, Calamy doesn’t seem like a movie star playing a working-class woman. She makes for a plausibly pretty Frenchwoman hell-bent on putting spaghetti on her cluttered kitchen table. Unable to land lucrative employment after taking time off to raise her kids, Julie struggles to escape her role as head chambermaid while contending with an ex late with alimony who never picks up the phone. Full Time depicts, in bracing detail, how rapidly single motherhood can throw one into economic precarity, even despite professional qualifications.

Eager to recount the physical and creative demands of the role, Calamy explains how “the first scene of the film — in the commuter train — we had to be able to do it in one take. We had to be ready and off the train by 6:00 a.m. We met at four in the morning, and from five to six, we had that one hour to train ourselves for how we were going to be getting on and off the train. It really was a challenge. But it’s the kind of challenge that I enjoy doing.”

When I comment on the taxing labor of working as a hotel maid, she emphasizes how seriously she took the responsibility of showing this job with dignity and detail: “This was quite new to me, the housekeeper’s work in this large luxury hotel. We did a special training where a number of hotel staff did a demonstration to show us how specific their work is — and how exhausting as well.” In Full Time, Julie’s ability to assuredly wield a power washer and spot the subtlest tchotchke out of place is how she manages her female team of maids across age, race, and background. “Many of the [actual] women who have worked in these hotels for a long time have developed tendinitis, back problems, and problems with their knees. The first time they did a demonstration about how to properly make a bed — and the speed with which it had to be done — we all applauded. It was really quite an amazing thing that they were doing.”

Full Time shook me, sped my pulse, and left me in tears with how seamlessly it intertwined the painfully personal with systemic inequalities. Julie’s story is hers, but it is always and abundantly that of the bone-tired multitude aiming to make rent. When asked if she considers Full Time her most political film to date, Calamy does not mince words: “This is a very political film because it’s the point of view of Éric Gravel. The conditions of work, the kind of poverty that underemployed people have to experience — not just for Julie, but for other people like her — really become a matter of survival.”

Across the film, Julie’s struggle to keep her job and care for her kids gradually leads to her own reckoning with the role she plays in a much larger network of power imbalances. “What’s interesting in this film is that when there are these strikes happening all over France, Julie doesn’t participate,” Calamy explains. “She’s not part of that movement right at that moment. But you can see that, perhaps down the road, the ideas and the sentiments that are being expressed by the strikers are something that come to, more and more, infuse her.”

Calamy is also quick to point out how integral Julie’s professional competence is to the integrity of her selfhood: “She’s someone whose identity is very closely tied to her work — an aspect that isn’t usually shown for women. Julie’s somebody who’s working below her level, and she’s really trying to get back to work at the level that she is qualified to do.” I don’t mention the film’s feminist undertones, and, as it turns out, I don’t have to. “Even though, by the end of the film, things ease up a little bit, Julie’s still caught up in this type of hell — that is, her daily life,” Calamy asserts. She extends our interview another five minutes, and I wonder if this will make her late for the next thing, whatever that next thing might be. “If you didn’t know, you would think that it was a woman who had directed this film because it really does see things from the female perspective. Full Time really shows that you don’t have to be a woman to be a feminist.”

One of the rare tenets of Gravel’s film is that it exposes how, within patriarchal systems that punish ambitious women (ambitious mothers especially), women themselves become more apt to throw each other under the bus. About 30 minutes in, when Julie is late to her morning shift and another maid, Inès (Mareme N’Diaye), has been forced to clean a suite on her own, we see the tensions play out with the precision of the fitted sheet they stretch onto a mattress. “Why not move closer?” demands Inès, when Julie blames her tardiness on her long commute from the suburbs. “Mind your own business,” Julie snaps back. “I won’t move my kids to a cubbyhole for you.”

When Inès, of African descent and justifiably pissed, retorts, “My place isn’t a cubbyhole,” it’s a beautifully uncomfortable moment. Julie may be our heroine struggling to make ends meet, but she’s certainly not inculpable of self-absorption, including white entitlement. A dog-eat-dog world can turn anyone into a bitch — and Julie can growl with the best of them. “When it comes to the amoral part of Julie,” Calamy reflects, “we have to remember that she needs to survive.”

Full Time reminds us of the very human toll of that survival — and how inhumane we can all become when we only focus on our own.

¤

Full Time opens in New York on February 3 and Los Angeles on February 10, with a nationwide rollout to follow.

¤

LARB Contributor

Eileen G’Sell is a poet and critic with recent or forthcoming contributions to Jacobin, Poetry, The Baffler, The Hopkins Review, Oversound, and Hyperallergic, among other outlets. Her first volume of poetry, Life After Rugby, was published in 2018; her second book, Francofilaments, is forthcoming in 2024 from Broken Sleep Books. In 2023, she was a recipient of the Rabkin Foundation prize in arts journalism. She teaches at Washington University in St. Louis.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Talking Cure: On Ruth Beckermann’s “Mutzenbacher”

J. Hoberman reviews Ruth Beckermann’s film, “Mutzenbacher,” loosely adapted from the 1906 novel.

Having a Job Sucks: Talking Sex, Labor, and Pre-Code Cinema with Amalia Ulman

Eileen G’Sell sits down with actress-filmmaker Amalia Ulman about her film, “El Planeta.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!