The Talking Cure: On Ruth Beckermann’s “Mutzenbacher”

J. Hoberman reviews Ruth Beckermann’s film, “Mutzenbacher,” loosely adapted from the 1906 novel.

By J. HobermanJanuary 10, 2023

CURRENTLY MAKING the film festival rounds, Ruth Beckermann’s Mutzenbacher is at once a literary adaptation, an observational documentary, a psychosexual thought experiment, and an open-ended investigation: Sigmund Freud filtered through Andy Warhol’s lens.

Beckermann, 70, has been making documentaries since the late 1970s, initially as part of a leftish video collective. On one hand, her films seek to make the past present. On the other, as Nick Pinkerton notes in a 2019 book on Beckermann, published by the Austrian Film Museum, she shows an “absolute openness to happenstance.”

Much of Beckermann’s work might be considered first-person, reflecting her own situation as an Austrian Jew. Released amid the worldwide upsurge in national populism, The Waldheim Waltz (2018) revisits the mid-1980s campaign to expose UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim’s wartime activities as a Wehrmacht officer. (Pinkerton calls Waldheim her “ultimate foil — the Austrian politician who would like nothing more than to forget all about the past meets the Austrian filmmaker who cannot and will not let it go.”) Other films are more literary. The Dreamed Ones (2016) makes a powerful drama out of two actors in a sound studio, reading the decades-long correspondence between writers Ingeborg Bachmann and Paul Celan.

Although all of Beckermann’s documentaries are unconventional, Mutzenbacher is her most radical use of an existing text. Assorted Austrian men appear before the camera to read passages from a notorious pornographic novel, Josefine Mutzenbacher, oder Die Geschichte einer Wienerischen Dirne von ihr selbst erzählt (Josephine Mutzenbacher, or The Story of a Viennese Whore, as Told by Herself), first published 1906. With the book as a Rorschach test, Beckermann refines the analytical method used in her 1996 East of War: rather than document the traveling historical exhibit War of Annihilation: Crimes of the Wehrmacht, she documented the memories triggered by the show as recounted by Viennese museumgoers.

Mutzenbacher’s source, anonymously printed in a private edition of a thousand numbered copies, is a pseudo-memoir in the 18th-century tradition of Moll Flanders or Fanny Hill. A now-retired prostitute recounts her scarlet past. Self-satisfied attitude aside, what distinguishes Josefine Mutzenbacher or Pepi is her extreme, even absurd, precocity. Born in a working-class district in the outskirts of Vienna, she had her first sexual experience at age five. Many followed. Her narrative ends with the onset of puberty, when, discovering that she can be recompensed for doing what gives her pleasure, she turns pro, a registered prostitute in Vienna.

Often banned yet continuously in print in both German and English, Josefine Mutzenbacher is said to have sold some three million copies, carving out a place in Austrian literature for its creative use of Viennese prole-speak, its flavorsome lexicon of sexual slang, and its significance as a work of cultural heritage. The decades have brought with them several softcore, comic film adaptations (with older actresses as Pepi). There is even a tour of Vienna named after Josefine Mutzenbacher that visits the sites of her fictional life.

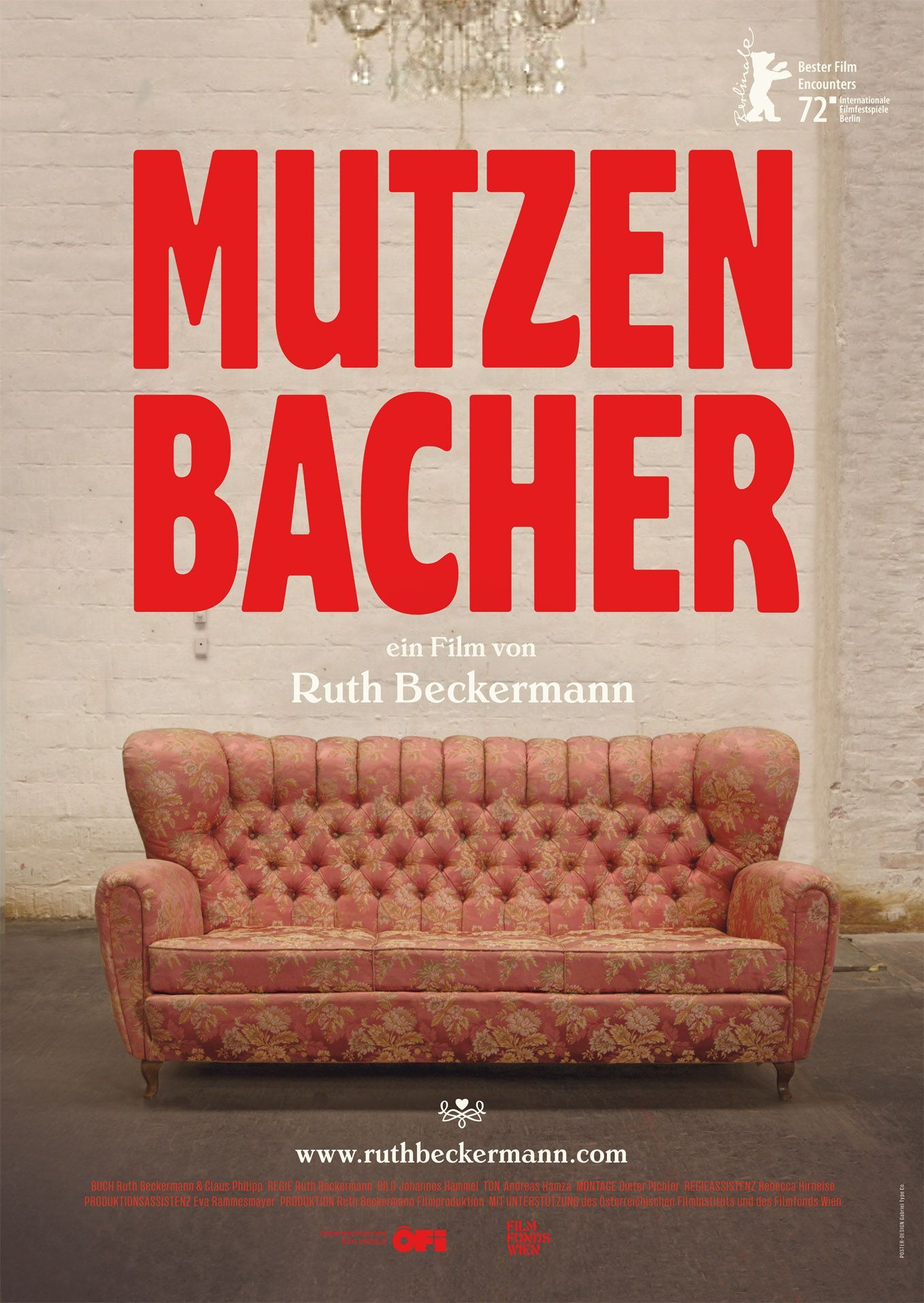

Set in motion by a newspaper advertisement seeking men between the ages of 16 and 99 for a film based on a well-known pornographic novel (no previous acting experience required), Beckermann’s movie is a casting call. Appropriately, much activity is centered on a pink and gold brocade couch that might once have enjoyed pride of place in a fin-de-siècle Viennese bordello, if not a certain doctor’s study. The location, a large, barren industrial space which previously housed a coffin manufacturer, could well have served the producers of bargain-basement porn films. The painted RAUCHEN VERBOTEN (“no smoking”) sign is a nice touch — repression required.

“I wanted to find out more about men today,” Beckermann has explained. Some 150 would-be actors responded to her ad, and she invited half to audition. Each man was given a passage from Josefine Mutzenbacher to read (or vocalize), which then served as a basis for her spontaneous follow-up questions. The strategy is not unprecedented. Miloš Foreman’s Audition, made in Czechoslovakia in the early 1960s, documented a bogus tryout for a singing job at a popular Prague nightclub; a decade or so later, Hungarian filmmaker Gyula Gazdag turned his camera on another set of auditions as the Budapest oil refinery’s Communist Youth Organization attempted to pick a politically correct rock ’n’ roll group to sponsor.

And then there is the model of Andy Warhol’s silent three-minute Screen Tests. For several years in the mid-1960s, Warhol turned a 16 mm camera on a seated, harshly lit visitor to his Factory, making hundreds of little films in which acting was strictly behavioral, direction sublimely indifferent. The film historian Callie Angell, author of the catalogue raisonné Andy Warhol Screen Tests, suggested that they be “viewed as a series of allegorical documentaries about what it is like to sit for your portrait, with each poser trapped in the existential dilemma of performing as — while simultaneously being reduced to — his or her own image.”

Frequently shot in close-up (subjects sometimes perched on the Factory couch), the Warhol screen tests were individual psychodramas. By contrast, Beckermann’s screen tests are miniature psychoanalytic sessions. If the prospective actors were unaware that the audition was the movie, Beckermann was as well — at least, until she saw her revelatory rushes, the initial prints of raw footage after filming.

Mutzenbacher orchestrates spontaneous reaction, its structure unobtrusive yet discernible. The first men we see are asked how they might play the child Pepi. Some take the question seriously. One appreciatively evokes the protagonist of Nabokov’s Lolita. Others are simply embarrassed. One man reads a passage written from the perspective of a five-year-old libertine and shudders in disgust. Most of the prospective actors were attracted by the subject matter. A few came to audition because they were familiar with Beckermann’s work and wanted to meet a famous director, thus giving her the opportunity to ask how far they would follow her directions.

The male response is hardly monolithic. In every case, however, Beckermann (heard throughout but never seen) takes advantage of the situation to guide her auditioners back into their own childhoods, repeatedly asking, “Does this remind you of anything?” After a long story in which Pepi describes a threesome involving a boy playmate and his middle-aged nanny, one young guy remembers his own secret about a nanny. (He used to sniff her underwear.) Others are pleased to volunteer their own porny adventures. Some are driven to free-associate on the current state of gender associations: if there is such a thing as “toxic masculinity,” why not “toxic femininity”?

Reactions to the text alternate between fascination and denial. One man reads a description of Pepi’s abuse by her father. Asked by Beckermann for a response, he pauses as if to consider and replies, “I think it was well written.” By way of further catalyzing, Beckermann often puts pairs on the couch and, as in an acting exercise, gets them to critique each other. (This is often spontaneous.) Pepi’s age is seldom discussed, although the guys often speak of her as though she were real. And for the first half of the movie, there is no mention that Josefine Mutzenbacher was written by a man and that Pepi is the product of male fantasy.

Mutzenbacher’s Schmutzenmacher was originally thought to be Arthur Schnitzler. However, Pepi’s anonymous inventor was almost certainly the feuilletonist Felix Salten, best known as the author of Bambi: A Life in the Woods, published 17 years later. Salten’s heirs may have failed to prove ownership of the novel in court, but few critics miss an opportunity to compare Bambi’s education with Pepi’s. Both books are bildungsromans, in which young creatures are eager to learn the ways of the world. If, as Salter liked to say, Bambi humanized wild animals, Josefine Mutzenbacher animalizes human sexuality.

In any case, it scarcely seems coincidental that, although set in the late 19th century, Josefine Mutzenbacher appeared only a year after Freud published his Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, causing no small consternation in its discovery of infantile sexuality. Pedophilia was already in the air, evident in the works (or lives) of Viennese writers and artists, including Adolf Loos, Oskar Kokoschka, Peter Altenberg, and especially Egon Schiele, repeatedly charged with the crime of representing a child’s nude body. Still, given the character of Pepi’s prepubescent temptress (and her talent for nongenital sex play), the novel might be seen as a parody of Freud. Even if it were appreciated more for its outrageous salaciousness than its bawdy humor, the latter is inescapable. Experiencing cunnilingus from a knowledgeable priest, Pepi recalls that her “bum danced a csárdás on the desk.”

The novel Josefine Mutzenbacher was rehabilitated during the late 1960s, when bans were being lifted in West Germany and Austria. The book was now appreciated as a liberating rebellion against sexual repression — which, within the New Left, included proponents of child sexuality. The name “Wilhelm Reich” is never uttered in the film, but some middle-aged men remember the good old days before the second-wave sexual revolution. One auditioner remarks that, although “abused by everyone” in several ways, Pepi remains a cheerful “sensualist.” Another observes that, unlike the women of today, Pepi seems to genuinely like and have fun with men. (Again, age does not seem to be an issue.)

Pepi’s shockingly unapologetic, outrageously sex-positive descriptions of child abuse and incest evoke the so-called “happy nymphos” of 1970s porn. Clearly, the novel harks back to a “simpler time” when men made the rules — to which many of the film’s subjects would return, at least in their imaginations. (I do not know the degree to which sexual violence is a political issue in Austria, but I can’t help noting that Austria’s best-known director, Michael Haneke, was an outspoken, early critic of the #MeToo movement.) Some, usually younger, participants in the film profess to be more enlightened. One guy wonders if the novel is an apology for men, while another makes a cinematic comparison. The men in Josefine Mutzenbacher are “like in [Lars von Trier’s] Dogville — they are all swine.” One of Beckermann’s youngest auditioners suggests that porn provides a script for sexual encounters — a “checklist” to work through — but, questioned by Beckermann, acknowledges that this may only be true for men.

Mutzenbacher raises questions of identification and empathy. In addition to regaling the reader with her own sexual experiences, Pepi — or should we say, “Salten” — occasionally reports on those of other, older women. The graphic-ecstatic recounting of an adulterous encounter by a self-described “proper wife” offers a coarse analogue to the Molly Bloom soliloquy that concludes Ulysses. A self-identified grandfather, one of the last men interviewed in the movie, pronounces the book vulgar. Beckermann coaxes him into reading this passage, in part by reading a bit herself. Allowing that — “The way you read it, it’s okay” — he embarks on the proper wife’s breathless description of multiple orgasms with marked enthusiasm.

What do women want? What do men want? What manner of transference or granted permission is happening here? Beckermann concludes Mutzenbacher as the book ends with Josefine’s estimation that she’s fucked 33,000 men — an “army”! (As if to foreshadow, Beckermann periodically has a chorus of 100 men recite key phrases in unison.) And what is it that the mature Josefine is said to have learned? “In the end, love is nothing but nonsense. All men do the same. Men pound women and women get pounded — and that is the only difference.”

Seemingly identifying Herr Salten’s unsentimental words with Beckermann, a theory-minded interlocutor at the 2022 New York Film Festival asked Beckermann if she was familiar with the idea of circlusion (an obverse way of viewing penetration). Sidestepping the question, Beckermann took ownership of the film in another way: “I never had the chance to speak to so many men about intimate things.” In other words, she set the table, and she turned it.

¤

LARB Contributor

J. Hoberman is the author of a number of books about cinema, most recently Make My Day: Movie Culture in the Age of Reagan (2019). For nearly three decades, he served as a staff writer and then later became the senior film critic for The Village Voice. Hoberman currently teaches in the graduate film program at Columbia University.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!