Every Encounter Is Singular: Gene Kwak interviews Askold Melynyczuk

Gene Kwak and Askold Melnyczuk take on low brow, high brow, and all brow.

IN SMEDLEY’S SECRET GUIDE to World Literature, Askold Melnyczuk — the author of three previous novels, all critically acclaimed — presents a voice to be added to the annals of great teenage narrators: fast-talking, wise-cracking, literature-and-sex-addled Jonathan Levy Wainwright.

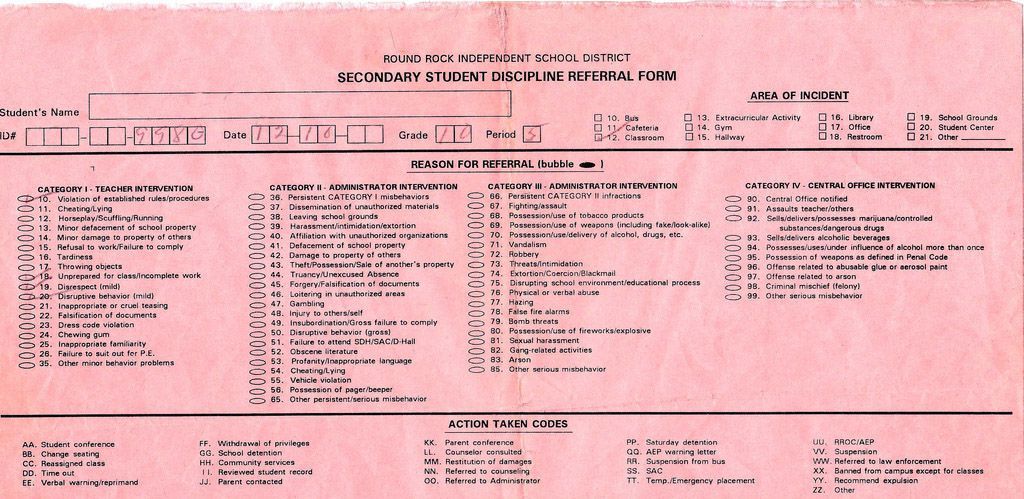

As the story begins, Jonathan’s parents are on the verge of divorce, and Jonathan, suspended from school for “pranks” as disturbing as they were disruptive, discovers that his Chinese girlfriend/bandmate is possibly pregnant. As recompense for his disgrace, he’s tasked by his poet-professor father with writing a history of literature in the age of Twitter. But since life at home (in Cambridge, Massachusetts) is turbulent (to say the least), Jonathan removes himself to visit his godfather, a criminal lawyer who is recovering from a stroke in Manhattan. There he meets and falls for the arresting Beyah, the daughter of his uncle’s caretaker, who has a face that is “coded by experts.”

Smedley’s Secret Guide to World Literature would have been a bold gambit for any writer. To take on the United States (where “now was all that mattered, since now was all that was”) from the perspective of a 15-year-old, albeit a bookish one, is no small accomplishment. The book walks a tightrope suspended between the world of Jonathan and his friends on one side, and the equally pressing yet barely comprehensible universe of adults on the other. This is “a book in which every adult will exult,” writes critic George Scialabba, noting that “Jonathan Wainwright is the lambent essence of today’s adolescence with its perennial urges and aches.” It’s true: Jonathan is richly rendered here — precocious and politically savvy, but also, like many a teen, completely naïve in affairs of the heart, his own and others.

I recently had a chance to ask Melnyczuk about youthful narrators, the influence of music, and the role of politics in literature.

¤

I dislike the terms “high brow” and “low brow,” but why was it important for you to write Jonathan as this “all-brow” character? Did you feel like that was an honest take on teenagers who, thanks to the internet, have all this knowledge at their fingertips? Or was it more about the freedom that this knowledge and awareness allowed you as a writer?

I love the term “all-brow!” As I recall from when I was that age — and as I observe the children of friends — it’s a period in which you resist the labels and judgments of your elders with heroic intensity. “I believe,” wrote André Gide, “the truth lies in youth; I believe it is always right against us.” That’s one approach. Then of course there’s this, from Joseph Brodsky: “My youth comes back to me. Sometimes I’d smile. Or spit.” Fair enough.

But I think it’s so common for us to “know” a lot more than we understand from a very early age. Emotional wisdom doesn’t come as part of a package deal — or at least, it didn’t, for me. I remember reading really sophisticated stuff like Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier or Hesse’s Steppenwolf, or Mann’s The Black Swan when I was 15 or so; long before I really grasped the stakes for which the characters in those novels were playing.

Speaking of stakes, at the start of the novel, they’re a bit ambiguous: What’s ailing Jonathan’s mother? What exactly got him suspended from school? What will happen to his possibly pregnant girlfriend? Some of this information is kept from the character, some withheld from both him and the reader. Did you worry that beginning this way might lose us? Did you play with that balance at all?

Excellent question. A lot of my revisions over the years focused on trying to find the right pace for revealing the backstory without turning the reader off to Jonathan or weighing the story down.

I tried to imagine just what Jonathan might be expected to know about his parents’ private lives — and, drawing on personal experience, I decided it wouldn’t be a lot. Don’t know about you, but I didn’t really care too much about my parents’ lives, except in the way they intersected, and often interfered, with mine, until I was in my later 20s. Until then, maybe because my Ukrainian refugee parents lived so much in the past, I wanted only to inhabit the eternal now.

Your mentioning your parents’ experience as refugees underscores a major difference between Smedley and your other three novels. They span generations and continents, but this book centers around a teenager from Boston. Was it hard to find the right tone? Do you remember the specific passage or sentence that gave you the confidence to write from Jonathan’s point of view?

The moment I heard “I’m lucky to be alive” — which was originally the novel’s first sentence — I felt I was inside a head not my own, speaking in a voice that wasn’t mine, but which nevertheless empowered me to speak freely. When that voice began talking about “the stun gun dildo of authority,” well, I felt I’d met a kindred spirit.

Jonathan kept making me laugh. I couldn’t help myself. But it’s precisely the distance — chronologically, sociologically — between myself and the character that allowed a degree of insouciant familiarity (whether its persuasive or not — reader must judge for themselves) which made working on this such fun.

But what was the impetus for writing about a teen?

I began the book during the run-up to the Arab Spring and the Occupy Movement, both of which briefly promised to be transformational before they imploded and collapsed from pressures external and internal. Part of my wish was to write something that fortified that rebellious spirit while illuminating the hazards of the course the rebels had chosen. I wanted first to inhabit and then to convey to readers the fearlessness of youth, it’s high-spirited laughter and brazenness. As a Buddhist teacher once pointed out to me, there’s a definite link between lightening up and enlightenment.

At the same time, I should note that this voice welled up just as my responsibilities toward my nonagenarian parents began picking up. Seven years ago, my mother began falling regularly, breaking a femur here, a humerus there, and as a result I was spending a lot of time in hospitals and nursing homes. These were not always happy places, and Jonathan’s wisecracks went a long way toward helping me maintain a sense of humor about things.

Did you do any research or pull from literary inspirations to nail the voice? Teen narrators abound in literature, but beyond the easy comparisons, I kept picturing Jonathan sitting at a lunch table in the high school of literature with Hal Incandenza from Infinite Jest and Simons Everson Manigault from Padgett Powell’s Edisto. They’re all bookishly witty and yet hopelessly innocent about the real world.

It’s a nice image! And I think Jonathan would be quite pleased to find himself in such company. However, as you might imagine, I avoided contact with books with similar narrators because I knew that comparisons would be unavoidable, yet I wanted this voice to cleave close to the truths of Jonathan’s singular experiences. I believed he could only speak truthfully to others if he spoke as himself. I will confess to regularly rereading Salinger’s Franny and Zooey, though the players there are all older than Jonathan.

Over the years I’ve met many astonishingly well-read young people — and it didn’t seem to me in the least far-fetched that a kid might sound as “learned” as Jonathan does. The “answers” to most questions are, after all, just a few clicks away.

But Jonathan’s not all about books and writers. He plays in a band — and he talks about musicians: Miles Davis, Subhumans, The Wankys, Neko Case. Can you discuss how you chose the music to include in the book? And will you talk about some of the bands that influenced you in your teens and 20s?

Music, like all art, is about transformation: the metamorphosis of experience, emotions, and ideas into sound. Youth, too, is intimate with transformation — it’s why I think most people are most open to music in adolescence. It speaks a language you alone understand. Part of the fun of working on Smedley was digging into what I imagined might be his musical scene. To research it I haunted Newbury Comics, read a variety of age-inappropriate ’zines, and surfed 4chan …

In my own life, music has played a larger role than I’d realized until I began working on the book. Growing up in the late ’60s and early ’70s, one naturally ran a soundtrack for one’s life — beginning in my case with the glorious music of the Beatles, Dylan, the Stones, Simon & Garfunkel, Pete Seeger, and so on. I still love and respond to a lot of that music. At the same time, I love what’s called the American Songbook, as well as a lot of classical stuff.

There were periods when I tuned out — I didn’t, for instance, embrace punk with the ardor of many of my peers. For a number of years I immersed pretty deeply into classical music, the familiar stuff, Gould’s Bach and so on, but also responding with intensity to the somber tones of the Hungarian Ligeti and the Ukrainian composers Baley and Silvestrov.

There was even a time when I listened only to Gregorian chants.

Did you ever play an instrument?

My parents took turns trying to teach me — my father gave me violin lessons; my mother taught my sister and me the piano, until we grew too unruly for her, at which point we were sent to Mrs. Gilmore … Neither instrument took. But some years ago, I picked up the trumpet, which I pursued with passion for five years before accepting I would never master my embouchure, and switching to alto sax. This new enthusiasm took me deeper into jazz than I’d ever gone before — so I’ve spent a lot of time over the last years listening to Miles, Dizzy, Arturo Sandoval, Satchmo (natch), and of course the otherworldly Tine Thing Helseth.

My friend J. Mae Barizo, a wonderful poet and master violinist, has turned me on to some interesting music, too. And I’ve been guided to fabulous contemporary recordings by the on-air reviews of my friend, Lloyd Schwartz, who reviews classical music for NPR.

I wanted to talk about consumerism and narrative. There’s been this sea change in marketing where every product has to come with a story. At one point, Jonathan mentions a pair of socks that have “their own website” where you can “trace the genealogy of the sheep behind it unto the fifth generation.” What’s this about, though? Is it because we suddenly value storytelling? Or is it just another capitalist angle meant to sell more goods and products?

According to The New York Times, Entrepreneur magazine calls “storytelling” “the major business lesson of 2014.” The Harvard Business Review, meanwhile, praises its “irresistible power.” Inescapable references to neuroscience abound. Researchers promise that good storytelling releases hormones also present in the breasts of nursing mothers, as well as during orgasm. Why am I not surprised? Fortunately, a few intrepid souls are determined to keep the novel from becoming another comestible appealing to the taste buds of savvy consumers.

Yes, we’re suckers for a story, and yes commercial interests have been quick to seize on some basic and not so superficial aspects of narrative seduction. J. Peterman’s catalog — remember Seinfeld? — was an early adopter. But, hell, public relations, the devil’s art, has been deployed by governments and businesses for nefarious ends for over a century.

A “good” story — a persuasive narrative — is powerful enough to suck an advanced, post-industrial nation like the US into war, after war, after war. A persuasive narrative and some baksheesh from the lobbyists.

Research shows that most of what we read on a screen is only skimmed for surface content. In the past, we’d put more value into something written by hand. And there was a clear separation in our brains between oral and written communication. But now, with texting and social media, we blur the two. Do you think writing by hand will ever completely die out? In the book, Jonathan comes across handwritten letters. He even tries to write a love letter of his own to Beyah.

The poignancy of handwriting! I keep finding letters from friends from the ’70s and ’80s, and then I also pore over letters in my parents’ and grandparents’ archives which stretch back over the last century. They’re hard to read, yes, but the difficulty is a part of the delight they give when you break the code of another person’s handwriting. Its idiosyncrasies force us to slow down, and slowness, noted Dante translator Laurence Binyon, is a kind of beauty.

I don’t write, myself. I scribble. Most things start out as hand-scribbled notes — on pads, envelopes, the endpapers of whatever book I’m reading at the time. Soon after, I type them up. My handwriting was described by someone as looking like a spider having a heart attack across the page. If too much time goes by before I transcribe it, I have a tough time reading it myself.

Yet there’s nothing like it — like writing with a pen, or pencil, on paper. It feels organic in a way a computer never will, not for me. Not even a typewriter comes close. Now I started as a poet, and I used to sit on a class taught by the great Derek Walcott — for my money, the finest English language poet of his generation, with a sensitivity to the natural world and an ear for a nearly Elizabethan sonority — and Derek always underscored that “you write with your whole body,” and pen and paper are the perfect seismograph for the soul.

As to the difference between literature and orature — I admire the hell out of some rappers and slam poets, but in the end I like sitting down alone with a book, pausing in mid-sentence, following a thought — provoked by the text — and then returning to the page, at my own pace. I have even learned to love defacing books with pen marks. And I find something terribly moving about seeing the handwriting of writers I love. One of my most cherished possessions is an envelope addressed to a friend by Dr. F. Kafka.

I hope that kids continue to learn to write by hand. One of the finest writers I ever taught was a young man who had fled Sudan — he was one of the so-called “lost boys,” though he’s a middle-aged man and a father by now — and he learned the English alphabet by writing letters in the sand. That may be the best way of all to learn cursive.

Do you hope this book connects to a teenage audience? Young Adult, as a classification, can be seen as just a marketing tool, but some view it as a helpful genre distinction. Such classifications notwithstanding, would recognition from that audience validate the authenticity of the voice or perspective?

Young Adult. No such thing. What can it mean to modify “adult” with young? The words seem designed to cancel each other out. If that’s the case, it reinforces Jonathan’s observation that there are no adults left any more. And I’m inclined to agree with him.

Yes, these categories help bookstores, schools, libraries, and parents “shelve” materials. But I suspect every adolescent really wants to get behind the PR, to hit the books kept out of reach. And our era is so determined to bulldoze genre distinctions, who knows what kind of hybrid will emerge — nonfiction in rhymed couplets might be an appealing outcome? Maybe not.

I do very much hope the book speaks to teens. I remember that period, between 13 and 18, as a time of great confusion, of wild energy ripping through the body, of great expectations for the future, of a certainty that our elders, who brought us World War II, Korea, and Vietnam — that they had gotten it all wrong, and that we were going to fix it.

And look what a great job we did.

Smedley is meant in part as a self-indictment, and a critique of my generation, whose pursuit of “personal fulfillment” has come at a cost to the common weal. It’s not like we couldn’t have worked harder to change the institutions and systems that have permitted inequality to grow to the point it’s reached today.

At the same time, the kind of mocking but affectionate laughter that is Jonathan’s defense against the world is rooted in his real affection, his plain liking of people, even the parents he’s rebelling against.

Earlier, you mentioned Arab Spring and Occupy. Jonathan and his friends — Rene, Astro, and Klyt — are politically aware. But critics of “Millennials” often lament their laziness and solipsism. And most literature that’s centered around youth is about the small world right before them. Why did you want to make the larger, political world a presence — both in spoken and unspoken ways — in the book?

As to the indifference of millennials, well, let me whisper two words: Bernie Sanders. And three more: Black Lives Matter. It may not be the 1960s but it’s definitely not the 1950s. The role social media played in each of these current political stirrings and crises all but ensures that everyone, from millennials to millennerians, is already involved or implicated in the politics of the day one way or another. Turning away is itself a choice. Also, Jonathan and his friends are in a pseudo-punk band, so they’re paying attention.

Then of course there’s the quiet but I hope potent presence of Jonathan’s mother whose shadow looms larger over the story by the end than readers might have expected. She was a heavy-duty activist in her day in a way that’s not at all uncommon around where I live (outside Boston). Jonathan refers to this part of his mother’s life ironically, but the truth is he’s quite proud of her. And we’re meant to note that she loses some of her moorings when she pulls away from engaging the world’s more public dramas.

But the problem here may be with the word “politics,” which has acquired — maybe always possessed — a negative aura. What I mean by the word is really nothing more than the values that different people bring to their relationships with others no matter the setting: do you deal with people as equals at work, at home, in your daily interactions? Or are you inclined toward ranking, hierarchy, and competition? My parents were born a few years after the Russian Revolution turned their world on its head in ways that initially appeared promising but which quickly darkened as power itself inflated the egos of those who’d seized it. The problem with revolutions is that they seem to eat their young.

But the truth is I’m not particularly interested in politics, as such. I am interested, can’t help but be interested, in how I get along with my neighbors. One great thing about teaching is that, very quickly, my neighborhood begins to include all kinds of people and worlds I might never visit, from Kurdistan to Nairobi to Helsinki. And somehow this necessary engagement drags us into politics. Still, my hope is to go deeper — our problems arise from our habit of conceptualizing. To turn experiences into concepts is to corrupt them. That’s why I value novelists: they insist on the materiality of individual encounters. Every encounter is singular.

To build off that, in his “history of literature” in the age of Twitter, nearly all the writers Jonathan chooses to write about are rebels. Activists. Have been in hard luck situations. Can you talk about your own selection process there? And did you consider that by giving the readers of your book these condensed versions of these real-life author bios you might be pushing the readers into looking deeper into these hard-barked authors who have somewhat fallen between the cracks?

I tried to draw up this list in Jonathan’s spirit — his interests are broad, he lives in an undeniably multicultural world, and literature is his window on it. There were many others on his list in early drafts, including the poet Paul Celan, and Tolstoy too. In the end, I trusted a mix of serendipity, old favorites, and new enthusiasms. Alain-Fournier’s The Wanderer has been a beloved book ever since I first read it when I was about 15. A strange, magical book, which keeps being reissued for a reason. Agnes Smedley was a new and bracing discovery — for me! Her courage and her story moved and inspired me.

The link you point out — that each has a dramatic backstory and that most (not all) found themselves engaged in some kind of social struggle — merely reflects the fact that the same could be said about most writers who have made a contribution to their art.

Let me offer a quote from the endlessly quotable poet-monk Thomas Merton:

Is the artist necessarily committed to this or that political ideology? No. But he does live in a world where politics are decisive and where political power can destroy his art as well as his life. Hence he is indirectly committed to seek some political solution to problems that endanger the freedom of man […] In every case the artist should be in complete solidarity with those who are fighting for rights and freedom against inertia, hypocrisy and coercion: e.g., the Negroes in the United States.

That was written in the ’60s. Ain’t it still the truth?

¤

LARB Contributor

Gene Kwak is the author of two chapbooks: Orphans Burning Orphans available from Greying Ghost Press and a self-titled collection available from Awst Press. He has published fiction and nonfiction both in print and online with The Rumpus, Juked, Redivider, Hobart, Electric Literature, and others. He is from Omaha, Nebraska.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Art of Disillusionment: Alejandro Jodorowsky and the Uses of Fiction

Jodorowsky’s masterpiece begins by lurching from violent episode to mystical encounter to cosmic sexual escapade — and the momentum holds through the...

Parents, Teenagers, and the Books in Between

In a society where people believe that “teenagers don’t care,” at least not about anything important, what is it like to read as teenager?

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!