It’s Not Even Past

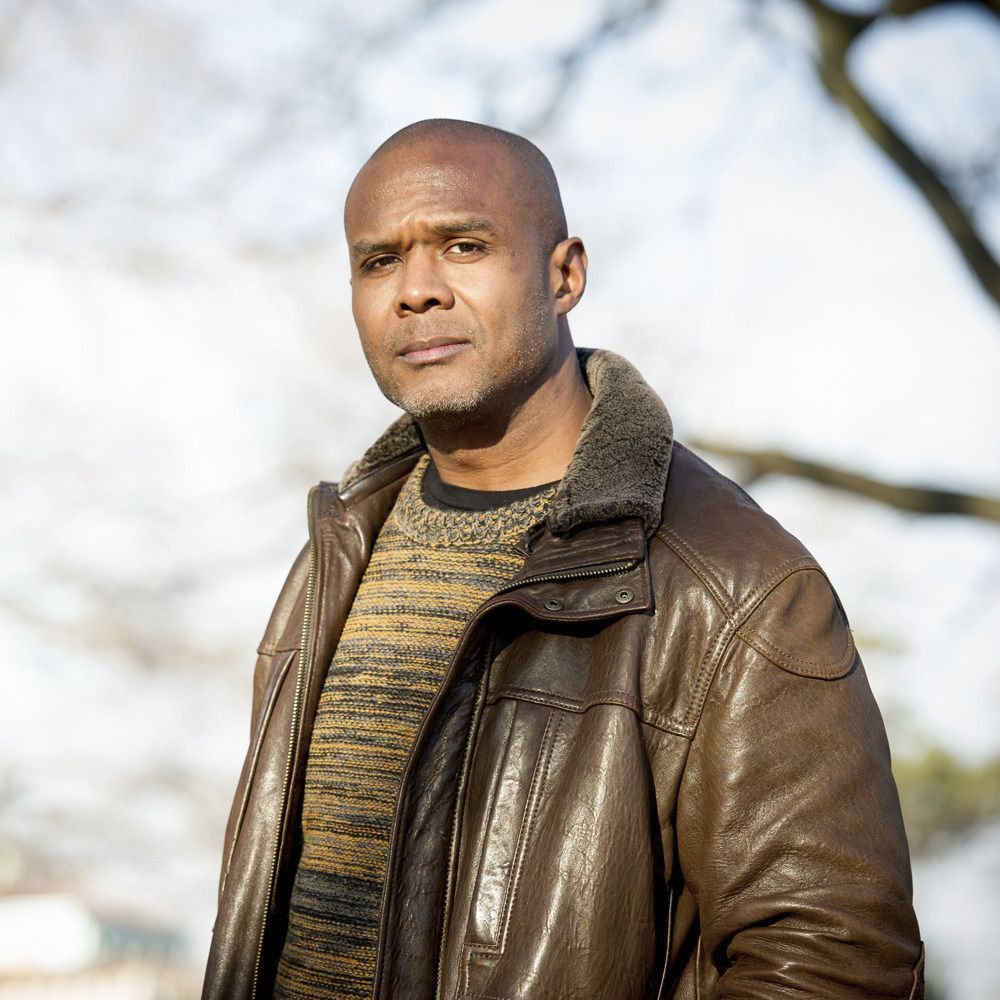

John Bowe and James Hannaham Discuss Delicious Foods, Nobodies, and Modern American Slavery

IN AN EMAIL EXCHANGE about his second novel, Delicious Foods, James Hannaham made a point of discussing the work’s biggest influence: John Bowe’s 2008 book Nobodies. Subtitled Modern American Slave Labor and the Dark Side of the New Global Economy, the book features Bowe’s reports on instances of modern slavery in Florida, Oklahoma, and Saipan.

The information came to me as a disturbing surprise — and apparently few Americans are aware of these horrifying situations, unfolding not only around the world but also here at home. Few reviews of Hannaham’s novel, which has been widely covered and praised, have mentioned the harrowing realities that inspired it.

Delicious Foods opens on 17-year-old Eddie Hardison, who has just escaped from a work farm in remote Louisiana. He no longer has hands; the narrative relates the events that lead to the loss of his limbs.

The Hardison family’s history is a tragic one: After a white mob murders Eddie’s father, Nat, Darlene flees Louisiana with their son and moves to Houston, where she becomes a prostitute and begins to abuse crack. Lured to the work farm Delicious Foods with the promise of legitimate employment, Darlene becomes a captive with other African-American men and women, shackled to the plantation by her drug addiction: the overseers provide the laborers with a constant supply of crack on credit, entrapping them in debt they’ll never be able to pay. After his escape, Eddie settles down in Minnesota; years pass, but he still hopes to save his mother.

Spanning about 25 years, Delicious Foods moves back and forth in time, depicting Darlene’s college years, her eventual enslavement in adulthood, and Eddie’s search to find her. The narrative voice shifts between a close third-person perspective that follows Eddie, and the antic, darkly amusing point of view of “Scotty,” the dialect-heavy voice of crack itself, that narrates for Darlene.

The two authors, Hannaham and Bowe, are friends. Their conversation, about Hannaham’s novel and the issues it explores, took place over Skype; it has been edited for concision and clarity. — Alexander Norcia

¤

JOHN BOWE: Why did you want to write Delicious Foods?

JAMES HANNAHAM: It was more or less inspired by the story of Joyce Grant, a woman who appears in your book Nobodies.

Can you explain what happened to Joyce Grant? And what happened — and what happens — to others like her?

Here’s the usual formula. A corrupt farm sends a van, and their management team convinces cash-strapped African Americans, or poor illegal Mexican immigrants, or any marginalized people who can easily be manipulated [into believing] that a great opportunity awaits them: picking fruit, harvesting crops, tending the soil. It’s a vague offer. On false pretenses — a livable wage, steady employment, good living facilities — these men and women are persuaded into the van, and they’re driven to the middle of nowhere. They’re so far away from any place that they can’t escape, even if they want to do so.

Once they arrive at the farm, they’re told they owe a couple hundred dollars for the trip, and they’ll have to pay for room and board as well. They fall into debt. Almost at once, they see that the conditions promised aren’t the conditions in which they arrived. Over time, they realize they’ve become enslaved. Those in charge keep them oppressed with various kinds of disorientation. Violence is popular. A language barrier can exist. Often, the recruits have a drug addiction, and management provides them with a constant fix on credit, causing them to fall further into debt.

Now, I wouldn’t say this is the norm of the agricultural world in the United States. But it’s the kind of phenomenon that only occurs in labor conditions that are already very bad to begin with. In other words, it’s a more extreme version of exploitation. In writing Delicious Foods, it was important to me that people not dismiss the novel as having nothing to do with their own lives: I wanted people to read it and be reminded of a job they had.

Really, though, learning about this whole situation made me lose my mind. After I read Nobodies, I decided that the topic would be the basis for the next novel I wrote.

Why did it make you crazy?

I started seeing everything on a continuum of labor abuse. It gave me what I’ve been referring to as “temporal dread.” That slavery, for instance, is continuing to happen to the same demographic: the same people, African Americans, and the same location, the South. I’m going to be quoting that Faulkner chestnut a lot: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

The “original sin” of America hasn’t disappeared. Why do we keep doing this to one another? So many people believe that slavery is over. As a black novelist, almost as a rite of passage, I wanted to write a novel that dealt with the legacy of slavery. When I read Joyce Grant’s account, I had something of an epiphany: I didn’t have to write a period piece, which was both a terrifying and exhilarating realization.

Did you find, as I did, all these newfangled ways people use to resort to the same old arrangements?

It’s almost like an addiction, and that was one of the biggest themes I hoped to confront, without literally telling Joyce Grant’s story.

Before we move forward, we should make clear a couple of things. Ever since the legal abolition of slavery, certain industries, especially agriculture, have gone on trying to figure out how to get cheap or free labor. This has meant tenant farming, chain gangs, imported labor from the Caribbean, undocumented Mexicans and Central Americans.

And in and among these are the crackhead and wino crews of Delicious Foods: the most disenfranchised African Americans in the South, who are tricked with a number of false promises, or held victim by their alcoholism or addiction. Aware of all this information, when you were first conceiving your characters, what did you absolutely want to include?

First off, I planned to write a novel that, in some manner, explicitly dealt with dismemberment. I chose to do that with Eddie Hardison. In the beginning of the book, with his hands literally severed, he builds a business as the “Handyman Without Hands.” That being said, I hope I don’t seem pedantic, or that it appears as if I was experimenting in areas that weren’t, foremost, in story. Setting up Eddie’s scenario, I felt I could explore a lot of questions I had about labor and race in America. Here’s Eddie, this extraordinarily capable young man who has discovered how to do something remarkable with no resources at all. In fact, there’s nothing that says labor more than your hands. It’s almost a cliché: losing your hands is losing your ability to work. Yet Eddie manages to flip that around in such a way I believe will register as very familiar to black Americans: your hands are gone, and now you have to find some way to work.

I’m reminded of Melville.

I adore Melville. He might be my favorite white writer of the past in America. A few months ago, I wrote a short essay in The Village Voice about how he seems so much more modern than anyone from the past. He was clearly a visionary. In my opinion, a lot of the subtext of Melville’s fiction seems to indicate his sexual attraction to men of color. I won’t try to impose that view, but I see it as a useful and provocative suggestion. You may not arrive at any “truth” with that reading, but it certainly stirs the pot.

We should discuss your humor. You seem to properly love and hate — appreciate and criticize — victims.

I try to be generous. I try to observe other people without judgment. It’s not only necessary: it’s fun. I look at the world neutrally. I attempt to report what I consider facts in order to lead people to make certain conclusions on their own.

Did you go through a trajectory? When I approached the issue, I had a straightforward, liberal template: slavery is bad; those who enslave are bad; those who are enslaved are good. I thought the oppressed were purely victims. After spending several years with the issue, however, I began to realize it’s not so simple, at least in some cases. Slaves are just as capable as lying in a trial, say, as anybody else. What do you do, then, with a victim who’s also a liar, or an exaggerator?

Maybe this is a difference between fiction and nonfiction: Those sorts of complications excite me. It’s equally shocking and thrilling to imagine the contradictions that exist in real life. To some degree, I view it as my job to make sense of the paradoxes of human nature. They are weird and surprising, and they make characters realer to me. In nonfiction, it’s probably vexing, especially if you have an activist mission combined with the reporting. I was entirely self-conscious that Delicious Foods would be a work of art and not a work of activism. I like the idea of one doing activism around the book, but I made it a point not to be didactic.

It’s a depressing topic, yet you do remain fair and hilarious the entire time. One of the ways you’re able to do so, I think, is with “Scotty.” How did you conceive a narrator who is, essentially, the voice of crack cocaine?

I’ve never wanted to write something that wasn’t funny. I’ve always had a personal annoyance with the received idea that serious literature can’t make jokes. Humor is a method of survival, and it’s vital to my fiction.

Still, Delicious Foods approaches a situation that is very upsetting, and I needed to find a way to power through it. At a certain point during the writing process, you said something to me: the subject is just a total bummer. After Nobodies, your next project was Us: Americans Talk About Love, almost as an antidote to having spent years with this dire and dark material. I had to create a space, then, to complete the novel, as I considered it an obligation to finish: I started to notice many people didn’t know about modern-day slavery, and of course, I thought they should.

I invented a narrator that helped me. I created the voice, as you say, of crack. I called him Scotty. It’s the nickname crack addicts give to crack. It’s a Star Trek reference: “Beam me up, Scotty.” Scotty narrates most of Darlene’s story. Partially, I made this decision because I had thought it would be Darlene’s voice: trashy, profane, and heavy in vernacular. Eventually, I realized Darlene’s character wouldn’t match with that voice: Darlene had to fall much further than I originally thought she’d have to fall. She changed from someone who was of a lower class to someone who had graduated from college and experienced a single, traumatic event: her husband’s murder at the hand of a white mob. That led her to drugs. That led to Scotty’s voice.

It also didn’t make much sense to have a drug addict character be completely lucid about what was happening. It seemed more realistic, paradoxically, to have crack speaking. The crack has a critical distance from the addiction.

You just wouldn’t think the novel could be so funny. But you see this with the people I interviewed in Nobodies. The people who are up against all of this despair, injustice, and gruesomeness are usually capable of being hysterical.

You have to have a sense of humor to get through it. If you don’t have a sense of humor, you’d just slit your own throat. But that’s not to say I let people off the hook. What drives the story, in a sense, are these oppressors who are able to compartmentalize or rationalize their actions so it doesn’t affect them.

I find that, in every slavery case, the oppressor argues he or she is doing a favor to the oppressed, and no one else can see it. For instance, in centuries past, the slaveholders claimed to be spreading Christianity to the poor savages from Africa. There are all kinds of false justifications espoused by people who all the while maintain a perfectly straight face.

How else can you do it? That was the whole subject of The Reader. A character couldn’t comprehend that what she did was evil. I think it’s fascinating how some people put a wall up between themselves and a certain self-criticism that would necessitate a larger context. I’m one of those who can’t do such a thing. I’m always trying to put myself in a larger context.

A lot of people don’t extrapolate the larger meaning of their lives, or their place in civilization. You clearly did extensive research.

A lot of Delicious Foods concerns wrangling information. I read a lot, and with the research in mind, I attempted to write without trying to prove to anyone that I did any research. I tried to leave a space for people who didn’t know much about modern-day slavery to learn about it. However, I’ve had to explain this course of action to a number of early readers. One person claimed I had done so well with Delicious Foods that it had to be, on some level, real. I like that attitude toward the novel. It produces a feeling almost akin to daydreaming, somewhere between fiction and reality.

There’s a great quote from Kevin Bales, who is the founder of a group called Free the Slaves. I’m paraphrasing, but he said that modern people pretty much universally find the idea of slavery to be abhorrent. The problem is no one knows what it looks like. And Delicious Foods proclaims this is one way it looks.

I do think people have a vague sense of injustices happening. We know, for instance, who makes our iPhones: the poorly compensated Chinese people who are jumping out of windows to escape their horrible work conditions. But I believe the farther away we are from the abuse and cruelty, the more abstract it becomes to us.

What about the elements of a historical slave narrative in Delicious Foods? I have in mind Summerton, the house of the white master. Or say, the slave songs.

I have a number of answers. One concerns the location. I decided to set the novel primarily in Louisiana for a couple of different reasons. Throughout Delicious Foods, there’s a running theme of people putting curses on each other. I like the idea of racism being understood as a kind of curse you put on someone’s body. I also spent three years in Texas, going to graduate school, and I was confident I could faithfully represent the area.

From there, I did strive to reveal links to the past. Many of the artifacts and much of the architecture from the 18th century and 19th century still exist. I hoped to muddle the distance between the past and present, to disorient the reader about the era.

Over the course of writing the novel, I did visit some sites that wound up in the story. My partner and I went to a plantation outside New Orleans where we saw 20 intact slave cabins. I had never seen anything quite like it before. These cabins had been in use, too, until the 1940s — not as slave cabins, exactly, but as housing for laborers. And of course, at the end of the street, we spotted a crew of Mexican men working on a construction project. It made me conclude that the world is a lot more like Blade Runner than we admit. Today, walking by old architecture gives me the sense of the present rubbing up against the past.

I have a friend from graduate school who lives on a Virginia farm that has been in his family for six generations. The house has a name. Essentially, it’s a well-preserved Southern plantation. Now it operates as an old-folks home for show horses. It was also the site of the first foxhunt in America. My partner and I visited a couple of times, and I couldn’t help analyzing my relationship to the building. What would I be doing if it were 1849? The place is like a stage set. There’s obviously a connection between architecture and people’s behavior. It influences them in certain ways. Some attitudes haven’t changed that much.

How do you change people’s attitudes then? Nobodies was aimed toward a political end, but you already mentioned that you didn’t have such a goal, at least wholly, for Delicious Foods.

I do see art as the activism of activism. Nothing is off-limits to criticize in art. In activism, you have to be certain of your mission, or your cause. The aims of art can be murkier. I noticed there was plenty of nonfiction work on modern-day slavery, but no one had yet tackled the emotional history, or the emotional costs.

I think the moral of the story might be more complicated and sadder than I ever imagined: If you expect people with power to share it nicely, you’re an idiot. If you don’t threaten the master with violence, nothing changes. But it’s in everyone’s interest for that not to happen. Rebellion is bloody and messy and disruptive to people’s three meals a day.

There’s definitely something to be said about a person just pleasurably getting through the day.

The ultimate responsibility lies with those who are oppressed, not with those oppressing. And that’s harsh. That’s not what I wanted to discover at all.

Congratulations, John. You’re an honorary black man now.

¤

LARB Contributor

John Bowe is a writer living in Manhattan. He has written for The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, and is the author of Modern American Slave Labor and the Dark Side of the New Global Economy. He is currently finishing a book about public speaking for Random House.

LARB Staff Recommendations

At the Borders of Our Tongue

David Mitchell, Unplugged

“Writing for future generations rather than your own is probably the best way of guaranteeing your own eternal oblivion.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!