Eternally Deferred Mystery: On Gabriela Alemán’s “Family Album”

Eugenie Dalland reviews the new story collection from Ecuadorian writer Gabriela Alemán, “Family Album.”

By Eugenie DallandJuly 15, 2022

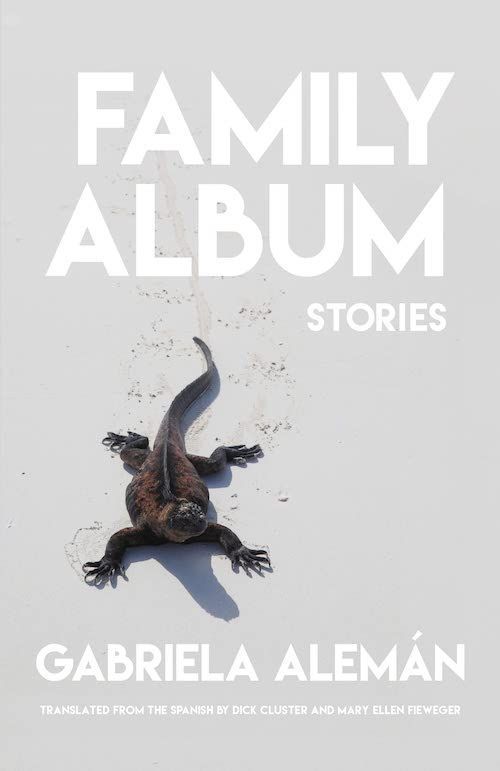

Family Album by Gabriela Alemán. City Lights Publishers. 120 pages.

ONE OF THE more peculiar qualities of the short story is the effect of mild astonishment after reading the final sentence that neither feeling nor intellect can fully explain. We may value a story for its message, language, characterization, or simply because we love the author; there are innumerable ways to write a story and just as many reasons to appreciate them. But there remains a kind of existential aftertaste that lingers beyond the last page, granting a degree of mystery to a literary form whose capacity to create lasting impressions feels disproportionate to its size. In brief, it may not always be easy to determine what a story is about, but it’s easy to sense that it’s about something.

Gabriela Alemán’s short story collection Family Album provides solid evidence of this mystery. The collection is being hailed as a follow-up of sorts to her 2018 novel Poso Wells, which was the first of the South American writer’s many books to be translated into English (Family Album, originally published in 2010, is the second). Alemán’s stories feature carefully wrought narratives and vibrant characterizations, and are written in a style with a remarkable lightness of touch. But these are also stories about stories — how they congeal and separate like liquid, how they morph and digress, their effects embellished and then stripped away. These subtle traces of self-reflexive questioning oblige us to consider something that metanarratives often overlook: what it feels like to engage with stories, as opposed to figuring out what they mean.

This slim volume includes eight tales that feature a diverse cast of distinctly painted characters, both real and imagined, whose fates are woven into the cultural tapestry of Ecuador (where Alemán lives). Loosely structured around the conventional milestones of familial life, the stories bear titles such as “Baptism,” “Family Outing,” “Marriage,” and “Summer Vacation,” yet the overall tone is anything but wholesome. The tales offer a series of deftly sketched portraits of nearly every human vice, lightened with startling humor (a blathering John Wayne Bobbitt makes an appearance) and profound sympathy (a scuba instructor in the Galápagos decides to grant a dying octogenarian’s wish).

Many of her protagonists are searching for something — often the truth — which they usually never find. Alemán rarely rewards her characters (or readers) with the satisfaction of a definitive conclusion or discovery, be it triumphant or abysmal, though neither are her endings self-consciously anticlimactic. Rather than reveal the truth about an attack on an indigenous Amazonian tribe, a guide who witnessed it converts to the beliefs of the American missionaries who initiated the slaughter; a journalist who finally uncovers the actual story behind the false one she’d written earlier loses the will to correct the record; a widow receives a shattering revelation only to turn the other cheek. It’s not apathy that drives her characters but an understanding that life requires blinders, and that more often than not, the hands that fashion them are our own. In a sense, her characters all have something to lose, until they realize they never had anything to begin with.

One of the more astonishing stories in the collection, “Costume Party” recounts the narrative of a journalist who for years sought the identity of a masked icon, the real-life Mexican film star and folk hero El Santo. On the cusp of learning part of the answer from the only woman who will share it with her, the journalist suddenly hesitates. She succumbs to the state of mind in which Alemán plunges many of her narrators: a kind of matter-of-fact resignation of the soul, not dissimilar to the legendary toska of Russian literature. This sentiment has many meanings but, for our purposes, can be crudely translated as a kind of despondency with no discernible cause. “What I did know, the only thing I knew,” Alemán’s protagonist acknowledges, “was that what she had told me had the shape of an arrow and that whatever I could speculate about its trajectory would only lead me to a target of my own invention. The distance between one thing and the other would remain there, devoid of an internal logic.” Further along in “Costume Party,” the author captures with surgical precision the essence of this inability to rationally grasp what a story means: “It didn’t matter who was behind the mask, because the eternally deferred mystery was the answer to everything.”

Despite the darkness of the collection’s material, it would be inaccurate to call the book pessimistic. The tone of Alemán’s contemplations is not a cold-blooded one but rather involves a nuanced approach that is at once compassionate and dispassionate. Alemán is a journalist of the highest order, with an eye for a good story, a nose for falsehoods, and a powerful curiosity that leaps off the page and into the reader’s imagination. (Her skillful prose style is effectively captured in Dick Cluster and Mary Ellen Fieweger’s English translation.)

Alemán was born in Brazil to a family of diplomats and athletes, and spent much of her youth abroad (in Ecuador, Paraguay, Switzerland, and New York City, among other places) before settling in Quito, where she now resides. She played professional basketball for Switzerland and Paraguay before receiving a master’s degree in Latin American literature and a PhD in Latin American Cinema. Her awards include a Guggenheim Fellowship and placement as a finalist for the prestigious Gabriel García Márquez Spanish American Short Story Award, among many other accolades. In an interview for this publication, Alemán explained that her peripatetic upbringing and athletic career exposed her, from a young age, to a vast range of people, and that her athletic experiences on a team sport taught her the importance of thinking as a collective. Family Album’s title, in this light, suggests not a saccharine embrace of togetherness-despite-the-odds but rather a commentary on the pitfalls and repercussions of a society hellbent on individualism.

While Alemán’s work features an uncategorizable mashup of genres (Poso Wells blended political satire, science fiction, and poetry), there’s value in considering Family Album through the lens of detective fiction. Many of her characters are cast in the role of journalists, for example, a figure she has described as closely aligned to the hard-boiled detective:

I tend to think that journalists in Latin America are superheroes and detectives all rolled into one. In Latin America, we don’t have a literary tradition of detective fiction. […] The closest we get to figures looking with tenacity for the “truth” are journalists. Usually without funds to carry out their investigations, usually with the establishment against them, usually without backup or time on their side.

Another reason to consider Family Album within the context of detective fiction is that the genre’s motifs do more than create tension: they represent how humans process meaning. We are plagued with red herrings, mysterious phenomena, misunderstandings, secrets, and subterfuge. We assign significance to things that have no significance, and the conclusions we arrive at are rarely the ones we expected. Most of all, we are inclined to assume things rather than investigate them — or even to acknowledge this inclination. By the end of Family Album, we are left wondering if the most dangerous crime recorded in the collection’s pages — more than the abductions and murders, oppression and colonialism — is that of assumption itself and what it enables: an aversion to learning whatever truth it is that we are avoiding. When the narrator of “Costume Party” is on the verge of learning El Santo’s secret identify from his former lover, she describes the moment of revelation as disconcerting yet transportive:

[I] didn’t know whether I wanted to hear what she was on the verge of telling me, though for the first time somebody seemed about to tell me something out of script. Something that hadn’t been rehearsed, something that due to its frequent handling had acquired the sheen of truth. The kind of thing that sometimes provides a reason to go on living, allows the present to hold together, and lets one imagine that what one sees is all there really is.

“Summer Vacation,” another of Family Album’s most riveting stories, dives into the real-life tale of the Baroness Wagner, who conned the Ecuadorian government out of land and funds in the 1930s. The narrator is a journalist who has written an article about the baroness and her scandalous behavior, based only on the sensationalized and flattering gossip of the time, much of it a fabrication by the baroness herself. As the journalist uncovers more and more about the actual story — one filled with murder and espionage — she stumbles upon an old report detailing the baroness’s arrival in Guayaquil from France, a report that specifically contradicts all the fabrications.

When I finished reading the report, I let out a chuckle. Suddenly, the baroness had become a person. She could no longer hide behind the veil of lies that had kept her at a distance. It was as if I’d found a childhood friend whom I couldn’t remember at all. The papers and photos had not only made her appear but had placed her in the present, under a new light.

“Perhaps the central question to be considered in any discussion of the short story,” wrote Flannery O’Connor, “is what do we mean by short.” The only thing that makes a short story short, she seems to imply, is its word count. Family Album stands as a testament to this spurious brevity, showing that the genre’s effect is deeper and more echoing than we may usually assume. Alemán’s strength is that she approaches the form not by intellectualizing it but by experiencing it, and it is through this lens that we ultimately perceive these seemingly small and emotionally resonant works of art to greatest effect.

¤

LARB Contributor

Eugenie Dalland is a writer and stylist based in New York City. She publishes the arts and culture magazine Riot of Perfume.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Writing from the Periphery and Renewing the Center: An Interview with Valerie Miles

Nathan Scott McNamara interviews editor Valerie Miles about Granta’s list of Best Young Spanish-Language Novelists.

The Many Souls of Clarice Lispector’s Translators

THIS PIECE APPEARS IN THE TRENDING ISSUE OF THE LARB QUARTERLY JOURNAL, NO. 30.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!