Entertaining Mr. Lambert

Hollywood of the 1950s, as Gavin Lambert was to discover on his arrival, was marked by secrecy and deceit.

By Alex HarveyAugust 31, 2015

AT A CROWDED New Year’s Eve party in 1956, the English film critic Gavin Lambert noticed an awkward but attractive outsider. The stranger, who had “powerful shoulders, a leonine head and graying blond hair, very handsome but gloomy […] seemed to create a circle of isolation around himself.” It was the American director Nicholas Ray. Still mourning the death of James Dean three months earlier, Ray was in London for the British premiere of Rebel Without a Cause (1955). Ray broke the ice by asking the younger Englishman what he thought of his noir In a Lonely Place (1950). Lambert replied that he liked the film’s ambiguous ending. “Exactly,” Ray said, “Will he become a hopeless drunk, or kill himself, or seek psychiatric help? They’ve always been my personal options.”

Bringing the admiring young Lambert back to his hotel suite, Ray handed him a photocopy of a New Yorker article and then disappeared into the bathroom. Lambert recalled:

It was three thirty in the morning so perhaps he had fallen asleep. I decided to take a look. As I reached the door, it opened and I collided with Nick on his way back, naked except for his underpants. He put his arms around me and kissed me on the mouth.

The next day Ray told Lambert about his two-picture deal at Fox. An adaptation of the New Yorker story was to be the first, and Ray wanted Lambert to help him write it. In the back of a limousine, en route to the airport, Ray announced to an infatuated Lambert that he’d already called the studio to arrange a green card. As a last word of advice before parting, Ray lectured Lambert on the need to disguise the fact that he was gay in Hollywood. “A butch handshake is very important,” Ray said, demonstrating his own bone-crushing grip.

Hollywood of the 1950s, as Gavin Lambert was to discover on his arrival, was marked by secrecy and deceit. Gay and lesbian actors, writers, and directors lived in constant fear of exposure, as studio heads and the press worked together to force out deviants, promoting a culture of heterosexual compliance. Yet the same bosses and columnists would collude in the protection of valuable homosexual talent, concealing actors’ identities under a cloak of make-believe normality and forced marriages. Hollywood then, as an industry and a place, was an extraordinary site of both repression and license.

Lambert took full advantage of Ray’s offer of a green card, spending most of his life in Los Angeles, writing for and about the movies. But he ignored the director’s cautious advice and remained openly gay. As a result, the collected works of this witty émigré Englishman offer the most entertaining and rewarding insights into the hypocrisy of gay Hollywood in the second half of the 20th century. More than any other film writer of his milieu, Lambert focused on the paradoxes of American cinema’s queer history. Aware of how much the movies he loved owed to a “gay sensibility,” he was also personally conscious of how concealed that sensibility had to be.

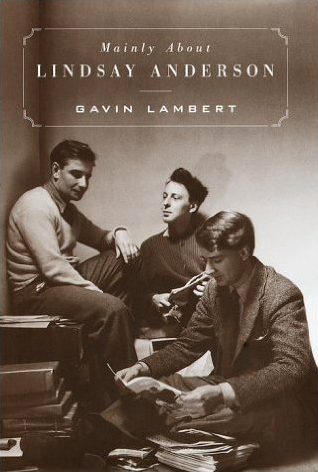

Lambert’s love affair with American movies started very early. As a boy at Cheltenham College, an elite English boarding school, Lambert made friends with Lindsay Anderson, who would become a founding director of the British New Wave in cinema. He shared with Anderson autographed pictures of his favorite American stars, obtained from an aunt who was an MGM screenwriter in the 1930s. As Lambert recalled in his memoir-biography Mainly About Lindsay Anderson (2000), “My personally inscribed photos from Norma Shearer, Spencer Tracy, William Powell and Myrna Loy enabled me to pull a little rank with Lindsay.”

Lambert sought refuge from the repressive realities of his public school in the illusive ideals of the movies. He knew that he was gay by the age of 11 and never questioned it. Lambert’s unapologetic openness about his sexual orientation would become one of his greatest personal and professional strengths — but it was hardly received as such in wartime England. Kicked out of Oxford University for bringing back American soldiers to his room at night, Lambert recalled, “My poor parents expected me to deny it. Instead I told the president that his informants exaggerated: In my first week here I picked up one GI in a pub.”

When interviewed by the military for National Service, Lambert tried to avoid the draft by dressing and behaving with complete normality, except for gold-painted eyelids. As Lambert had predicted, he was classified as unfit for military service, allowing him to enjoy the sexual opportunities of wartime London, with its helpful blackouts and queer pubs, where one could pick up American servicemen and British sailors on leave. By day, Lambert pioneered a new generation of serious film criticism in Britain. Taking editorial direction of the British Film Institute’s previously moribund journal Sight & Sound, he commissioned pieces from Tony Richardson on Luis Buñuel and Karel Reisz on A Place in the Sun. Despite his role in preparing the critical groundwork for a new wave of British cinema, England’s drabness and sexual conformity repelled Lambert: “You’re all making films about life here and now in this country, while I can’t wait to get out of it,” he confessed to Anderson. The infamous flight to Moscow by gay English spies Burgess and Maclean prompted a moral crusade against homosexuals in England, which led to thousands of prosecutions and numerous suicides. Against this backdrop, it was only a matter of time before Lambert would find his means of escape from England.

The two pictures that Lambert came to America to write for Nicholas Ray, Bigger Than Life (1956) and Bitter Victory (1957), gave him immediate entry into the studio system. Even with the studios’ control over actors and directors starting to slip, Hollywood in the 1950s still held an extraordinary concentration of glamour, power, and deceit. Shortly after arriving, Lambert was shocked by the violent death of his friend James Whale. The gay director responsible for early camp horror films such as The Invisible Man (1933) and The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), Whale had flung himself into the shallow end of his swimming pool, shattering his skull. He left a note, declaring, “The future is just old age and pain. I must have peace and this is the only way.” Lambert was puzzled as to why Hollywood buried Whale’s suicide, seemingly content to allow lurid rumors of murder to circulate. Fritz Lang put him right: “We are supposed to be living in paradise here, so killing yourself is a betrayal of the community image […] More than one reputation has been ruined by it.”

At the time, Whale was the most prominent voice of an alternative queer cinema ever to work in the studio system. Sharing his Spanish villa in Los Feliz with his boyfriend, the producer David Lewis, Whale was one of very few in the Hollywood community who dared to live an openly gay life. After the “moral clamp-down” enshrined in the Hollywood Production Code of 1930, which all studios voluntarily promised to obey, Whale’s camp aesthetic and his movies were deemed unacceptable. So, too, it would seem, was his life.

Hollywood’s sexual self-policing under the Production Code led to extreme double standards, which Lambert would build a second career exposing. One of the most fascinating ironies, as Lambert later detailed in Mainly About Lindsay Anderson, was manifest in Frank McCarthy, Hollywood’s “gay general.” After a distinguished spell in the US forces, McCarthy became an official censor for the movie industry. While his feared namesake, Senator Joseph McCarthy denounced an industry supposedly riddled with “Commies” and “queers,” Frank was in charge of policing the morals of 20th Century Fox. At the time, he shared a house in secret with his lover, Hollywood publicist Rupert Allan. As Lambert recalled, “I used to watch him and his lover arrive separately at parties with separate girlfriends, and they’d act surprised to see each other. ‘Oh, how are you?’ and all that. It was hilarious because everyone knew what was going on. But that’s the way things were.”

In 1959, holed up in his writer’s cottage on the 20th Century Fox lot, Lambert wrote his first novel, The Slide Area. Indebted to Christopher Isherwood’s Goodbye to Berlin, the book is a series of fragmentary but interconnected episodes held together by the first-person narration of a screenwriter, amused by Hollywood’s self-deception. Ray appears in the novel, thinly disguised as Cliff Harriston, a grizzled alcoholic director battling with an aging Hollywood diva who clings to her throne (loosely based on Joan Crawford). Ray found his character “affectionately truthful,” reassured that Lambert had transformed their gay relationship into a fictional heterosexual affair with a young actress. Isherwood, who became one of Lambert’s close friends, thought highly of the book, which turned the camera’s voyeuristic gaze onto Hollywood itself.

In his next novel, Inside Daisy Clover (1963), Lambert deepened his critique of Hollywood’s hypocrisy. The narrative features a love triangle between a willfully disobedient teenage starlet, a closeted gay movie star, and a sadistic studio boss. Although most of the book is set in Hollywood’s Golden Age, Daisy, the titular starlet, feels contemporary — a projection of the emerging spirit of the ’60s. Natalie Wood was perfectly cast as Daisy in Lambert’s own screen adaptation, but the film suffered from clumsy studio interference. The repressed gay actor, played by Robert Redford, was deemed unacceptable for general audiences, and only a couple of throwaway references to his bisexuality survive in the completed movie. As a result, the character’s motivation becomes opaque to the point of unintelligibility. “A pity because there were all these kinds of things that would have made the film more adventurous than it turned out to be,” reflected Lambert, years later. But enough of Lambert’s exploration of Daisy’s coming-of-age in a closed world — the all-consuming studio system — survives, and Christopher Plummer excels as the abusive, tyrannical producer, embodying the old Hollywood order, challenged by the nonconformism of new times. The last image of the film shows Daisy striding away from her studio-bought beach house. It is set ablaze behind her, as she moves forward toward an unknown future.

That Lambert could even write gay scenes — or hope for a more “adventurous film” — signaled the start of a new era of sexual openness in Hollywood. Lambert’s old friend Tony Richardson, who won an Oscar for his direction of Tom Jones (1963), began to live an openly bisexual life, and Curtis Harrington, another member of Lambert’s circle, directed films known for ironic sexual ambiguity like Night Tide (1963), with Dennis Hopper, and What’s the Matter with Helen (1971), with Debbie Reynolds and Shelley Winters. By the time Lambert wrote The Goodbye People (1971), a Los Angeles–based novel set in the Age of Aquarius, there was no need to evade the main character’s queer sexuality. In this thinly disguised self-portrait, the narrator of the novel enjoys a physical relationship with Gary, a handsome draft dodger with a buckskin jacket, bleached Levi’s, desert boots, and a desire for ice cream after sex. But it’s a relationship that cannot be sustained. Gary slips away like all of the “Goodbye People,” who find escape in sexual promiscuity or withdraw into drugs and the occult:

It used to be much simpler. Either you withdrew passively to simple hills and lived in peace the way nature is supposed to, or you chose militancy, staying in the world to protest against it. Now, withdrawal itself seemed to be turning militant. According to Godson, anyone who stayed in the world was weak, passive, a dupe. The true strength and the only action were up here in the mountains, protected by guards.

Lambert was both attracted to and worried by this new Californian generation, which moved so quickly from rebellion to disillusion. He admired their sexual openness and antimaterialism but was threatened by the looming nihilism of their lifestyles. Instead of highlighting the comically furtive, two-faced secrecy of old Hollywood, Lambert portrayed a different, spaced-out Los Angeles, lost in moral decay. He contrasted the bright openness of the Californian light with the dark, unsmiling eyes of its inhabitants — the alienated, listless youth who wanted to look inward but found nothing but empty recesses.

The final section of The Goodbye People describes the lesbian attraction between a reclusive film actress and a young, lost Californian girl — or rather, how the “spirit” of the former begins to possess that of the latter. Indeed, the young girl only “comes alive,” when she is haunted by the ghost of another woman, one who is almost, but not quite, dead. An extended metaphor for the hold of Hollywood over our collective imagination — the way it penetrates and reflects the world of our dreams — The Goodbye People reveals a city of sleepwalking addicts, infatuated with the unreal, and seeking release in pretense. As Lambert wrote, “Seduced by thousands of movies that concentrated on the pursuit of happiness, thousands waited for their own movie to begin.”

It is the very reason that Lambert himself moved to Los Angeles, wanting to feature in the movie of his own life. Adept at reading the queer subtexts of mainstream cinema, Lambert found, in the dazzling glamour of MGM musicals, a world to which he wanted to belong. Even the false landscape of Hollywood provided a continued escape, an extension of the movies into everyday life:

In those days, before too many of its landmarks had been demolished or ‘remodeled’, Los Angeles looked to me like the greatest back-lot in the Western World. Its microcosm was the 20th Century Fox back-lot, where I sometimes took a walk along the medieval French village street that lead to a Dali landscape, a field of dry grass scattered with detritus, a broken spotlight, an oriental archway, a stagecoach with the wheels missing, a flight of stairs leading nowhere. It stirred my imagination in a way that England never did.

The type of cinema produced by the old studio system — the formative cinema of Lambert’s generation — was more or less obsolete by the 1970s. He was increasingly drawn to figures who represented earlier artistic models like George Cukor, the subject of Lambert’s first biography. A closeted homosexual for most of his career, Cukor was one of classical Hollywood’s most prolific and successful directors. In On Cukor, Lambert wrote, “Looking for a single word to describe both [Cukor’s] life and the work, I think ‘discreet’ is the best. It implies delicacy, prudence and something enigmatic. The ‘I’ exists but doesn’t care to advertise itself.” For both men, cinema at its best was an art of pleasure, humor, and discreet sensuality.

During the last 25 years of his life, Lambert turned exclusively to nonfictional works, excavating American cinema’s queer past through the lens of particular stars. His biography Nazimova (1997) was the first history of the great silent movie actress Alla Nazimova, who had had affairs with both of Rudolph Valentino’s wives. Nazimova’s home on Sunset Boulevard — a lush tropical playground, which she cleverly named “The Garden of Allah” — was the setting for lavish lesbian soirees. As her sister told Lambert, Nazimova would sit “like a goddess, surrounded by these adoring neophytes, usually insignificant actresses.”

By mining Hollywood’s history, Lambert was making a virtue out of necessity, as the aesthetic of New Hollywood cinema held little interest for him and scant employment prospects. Nothing could surpass his beloved, glittering world of MGM stars. Unlike the rest of the prominent studios, which routinely consigned much of their old product to the junk heap, MGM had a long-standing policy of preserving its films — as Lambert did in his prose.

Lambert’s best book is his biography Norma Shearer, which returned to the very MGM star whose signed publicity shot had endeared him to Lindsay Anderson 50 years earlier. Shearer’s biography served in part as pretext for Lambert to explore the historical bond between “celluloid women” and gay and lesbian audiences. He was captivated by Hollywood divas’ on-screen presence, which seemed to access an open structure of feeling, alien to postwar heterosexual masculinity. Lambert himself was a very close friend and acolyte of one of the last studio-produced “celluloid women,” Natalie Wood. Like Shearer, Wood was an actress who deeply needed the company and reassurance of gay men. “This loneliness won’t leave me alone” was the lyric scribbled down in her last handwritten message. The note was found on the boat, moored off Catalina Island, from which she either slipped or jumped to her death.

Lambert’s biography of Wood, written shortly before his own death, exhumes the deep melancholy of his beloved friend. In her best movie roles, he found that Wood’s characters shared the paradoxical quality of his own life: resilient yet vulnerable, socially precocious yet marked by loneliness. Coming of age, like Daisy Clover, as a child actress at the heart of Hollywood, Wood exhibited a restless conflict between performance and interiority. One of the best scenes Lambert wrote for her in Inside Daisy Clover probes this tension, as Daisy enters into a sound booth to post-synch her voice to a musical number:

As the loop of her close shot in the movie appears over and over again on the screen, she finds it difficult, then impossible, to sychronise its lip movements. Permanently out of sync with her star image on the screen, the real Daisy beats on the glass wall of her cage in a hysterical attempt at escape. Then she screams.

Nazimova, Shearer, and Wood — three divas from Hollywood’s Silent, Golden, and Postwar Eras — all exhibit this paradox of identity. In one very real sense, this is what gay and lesbian actors, directors, and writers throughout the history of Hollywood always had to live with: the command to accept a false identity and a dual persona. Perhaps ironically, for Lambert, this paradox was liberating. The protean possibilities of cinema stars fulfilled his desire to move beyond the self — to project beyond the screen and to take on the identities of others.

Indeed, throughout his long relationship with American cinema, Gavin Lambert was drawn, ghostlike, to inhabit this shape-shifting landscape and medium. As a gay Englishman, his relationship to Classical Hollywood would always be one of alterity and voyeurism. Obsessed with the studio system, its legacy, and its secrets, he nonetheless remained distant. He was a privileged but critical outsider, someone forever caught, as he himself wrote, in a reverie between that “broken spotlight” and that “flight of stairs leading nowhere.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Alex Harvey is a writer and director based in Los Angeles. His book Song Noir: Tom Waits and the Spirit of Los Angeles was recently published by Reaktion Books in the United Kingdom and University of Chicago Press in the United States. He is currently making a film about Satyajit Ray and Kolkata.

LARB Staff Recommendations

On the Hoof, On the Barrel: “On Prime Cut”

"Prime Cut" is a sardonic report from the battle to define what America was and who it was for.

The Cartoon Bodies of “Mad Max: Fury Road”

"Mad Max: Fury" Road" is a live-action film with a distinctly cartoon sensibility.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!