Dysphoria Blues: On Luke Dani Blue’s “Pretend It’s My Body”

Grace Byron reviews Luke Dani Blue’s “Pretend It’s My Body.”

By Grace ByronFebruary 14, 2023

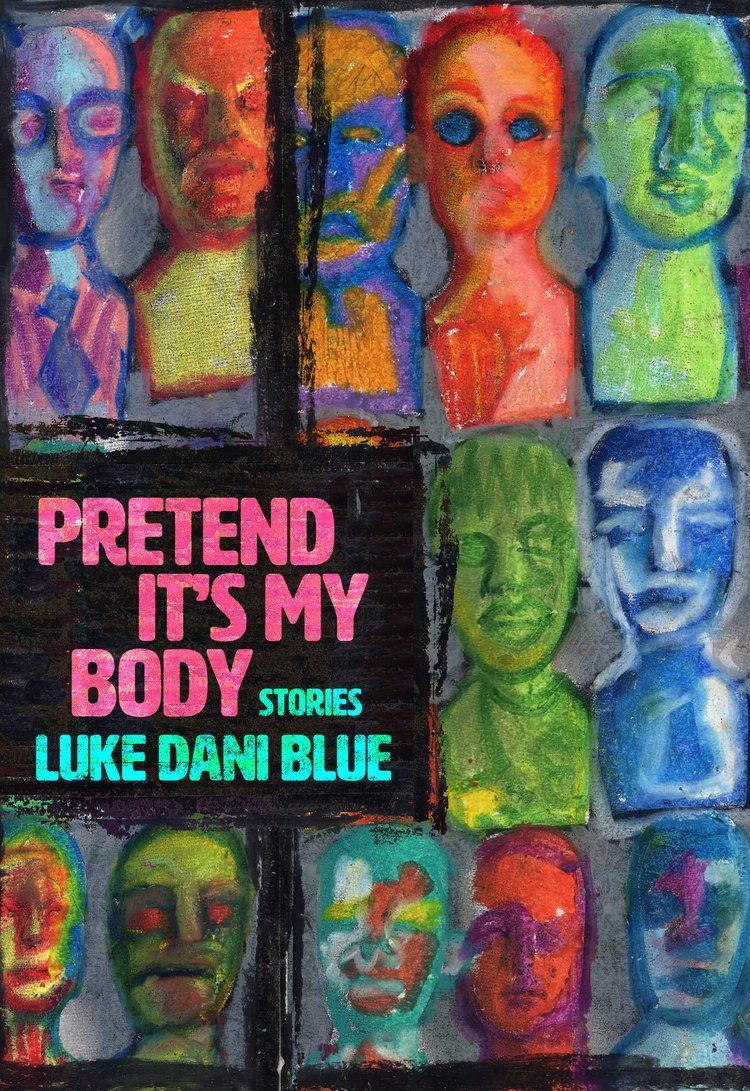

Pretend It’s My Body by Luke Dani Blue. Amethyst Editions. 256 pages.

JUST ANOTHER CASE of the dysphoria blues. Between online avatars, dysfunctional families, unruly Zoom rooms, and the ever-present threat of violence, the characters of Luke Dani Blue’s debut story collection Pretend It’s My Body struggle to feel at home in their bodies. Many are caught in gender friction, a stasis where change and staying the same both seem impossibly miserable. Pretend It’s My Body does not present easy narratives about relieving that friction; instead, Blue questions the way legible gender creates social mobility. This is the sticky, grim mess Blue leads us through, populated by paranoid mothers, women who may be men, and those who wish to do away with gender altogether. Apocalypse comes in small and big packages: a tornado roaring across the countryside, the Holocaust reaching Lithuania, fake shamans arguing over children, or the sun obliterating the planet as a girl goes down on her best friend who “smell[s] like sweet ruin.”

Blue often reaches for strange, inexplicable events to mirror the role of gender in the lives of their characters. “My Mother’s Bottomless Hole,” for instance, follows a woman named Hannah whose mother is buying a literal bottomless hole for their backyard. Hannah, who is plagued by gender trouble, fails to see a life beyond the one she’s living; instead, she is watching her life foreclose new possibilities, getting smaller and smaller as the hole gets bigger and bigger. She becomes weighed down by quarantining in a small town, sucked into the void of teaching and being the faculty sponsor for a Gay Straight Alliance. Both her mother and her students seem to feel that Hannah isn’t being honest about her gender. “If my mother said that I had always been a man, the genie would have escaped. I would have to become what I ached to be but of which I was petrified.” Hannah can’t imagine the freedom her GSA students feel, instead wishing they would encounter the mountain of transphobia and homophobia she knows all too well after having lived a bit longer. “I sometimes wished a small hate crime on my GSA students,” she sneers, thinking, “as if any of them knew what debt felt like […] prostrating before your friends with a tin cup.”

In another centerpiece story, a young woman named Suzuki wants to upload her consciousness to the internet and get rid of her body altogether. She chants what she learns in therapy: “I am in my body, not of my body.” She begins to dissociate from the world, not caring about the chattering woman next to her on the plane or being forcibly removed from a ball pit in a fast food restaurant. Even so, she can’t understand why her mother eventually comes out as a trans man. One bodily transition does not lend itself to understanding another. Suzuki can’t link the way they may both feel that “anything would be better than being trapped in a body.”

Wendy, the protagonist of the story “Crush Me,” short-circuits as she navigates the wilderness of friendship. She has a good job and a man who loves her. But in many of these stories, the problem is not having something; it’s having the right thing. There’s an itch that undoes everything else. In this case, the itch is a more traditional literary device: an affair. The thing Wendy wants most is an intimate relationship with her friend Jillian, a lesbian in a committed relationship. Even Jillian’s friends seem to see through Wendy, believing she’s a repressed lesbian, but Blue digs deeper into these psychic wounds. While Wendy cannot commit to her relationship nor confess her feelings to Jillian, she begins to see boulders moving along a riverbed. The failed coming-out narrative becomes imbued with the power of magical realism. Wendy becomes obsessed with convincing Jillian the boulders are moving, but ultimately fails. Instead, she and Jillian drift. Wendy is not someone who knows how to think positively, nor, she admits by the end of the story, has she ever wanted to.

In “Other People’s Points of View,” a trans girl in elementary school can read people’s minds, though she struggles to change them. Blue’s work often mines the intergenerational differences of queer people. The easy narrative is that things have gotten easier, but Blue complicates this through depicting children who still fight against parental apathy, internal confusion, and systemic inaction. Reading the story in the wake of recent bills that would ban minors from accessing trans-related healthcare is all the more chilling.

Sometimes, Blue’s stories get bogged down in the same haze that their characters do, which raises the question — how do you clearly write about the fuzziness of not knowing? The strength of Blue’s stories is the way they take seriously the lost, confused, and dysphoric without making judgments about how their lives could or should be. They are certainly responsible for navigating their lives: “Sly says it’s because I’m trans, but I know it’s not. Trans guys figure out those things too. Everyone does.” But they also bump into powerful mechanisms beyond their control. The ability to transition and reclaim bodily autonomy is a rupture against multiple systems, from the medical-industrial complex to the family unit.

The final story, “Dogs of America,” focuses on Avi, a trans guy who is still wrestling with staying afloat even after figuring out some of the basics. His friend, tired of having him on her couch, has finally kicked him out. He tries to scam the bus system and ride across the desert and on to Michigan so that he can reunite with his family. He’s worried about the reunion since his parents recently converted to Christianity. Avi’s friend thinks this is hypocritical — haven’t they both undergone a transition of sorts?

Near the end of the book, a mother buys a camper in the hopes of securing a better life for her daughter. “To drive was to become pure movement,” she thinks. It reminds me of Maria, the eternally biking narrator of Imogen Binnie’s Nevada. My friend recently read Nevada and told me that they related to the way Maria found biking to be a space free from dysphoria. Pure movement. Even within the daily grind of living as a trans person, spaces like these exist and point to the ways we can slip in and out of our bodies, upload and download the digital and physical avatars we so badly crave.

¤

LARB Contributor

Grace Byron is a writer from Indianapolis based in Queens. Her writing has appeared in The Baffler, The Believer, The Cut, Joyland, and Pitchfork, among other outlets.

LARB Staff Recommendations

They Toss Bodies at You: On Mariana Enríquez’s “Our Share of Night”

Elizabeth Gonzalez James reviews Mariana Enríquez’s “Our Share of Night.”

Fracture and Assembly: On Lizzie Borden’s “Regrouping”

Laura Nelson reviews Lizzie Borden’s “Regrouping.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!