A Dirty Baker’s Dozen: My 13 Favorite Crime Novels of 2014

Woody Haut's favorite crime novels of 2014.

By Woody HautDecember 19, 2014

ONE MIGHT ARGUE whether these were beyond a doubt the best crime novels of 2014, but they were certainly my favorites.

(In no particular order.)

A Man Lies Dreaming by Lavie Tidhar (Hodder & Stoughton)

It’s 1939, a writer of Yiddish pulp fiction, Shomer, is ensconced in Auschwitz. There he imagines Wolf, a once-formidable German dictator, having escaped his native land following a communist takeover, working in London as a private eye. But Wolf, the humiliated schlemiel, who must suffer repeated indignities, isn’t the only ex-Nazi in town. The Big Smoke happens to be filled with émigrés, though Wolf’s paramour Leni Riefenstahl has decamped to Hollywood, where she’s starring opposite Bogie in Tangiers, a parallel-universe Casablanca, written by F. Scott Fitzgerald. Meanwhile, fascist Oswald Mosley is about to become prime minister. Reality and fantasy served up in subversive proportions by the author of Osama.

The Fever by Megan Abbott (Little Brown/Picador)

The latest entry from the new Queen of Noir. This time instead of cheerleaders, it’s the clique at the local suburban high school where illness and hysteria have made inroads into the female student body. Understanding teacher-dad Tom appears unflappable until offspring and parents cause him to lead with his chin, as Abbott proves once again there is nothing more noir than public education, particularly when mixed with the teenaged chattering classes. For me, not quite as good as her last couple outings, but unforgettable and affecting enough to give you nightmares.

Perfidia by James Ellroy (Knopf)

Close to 700 pages of hyper-driven narrative, forensic detail, fragmented vernacularisms, and fevered declarations, delivered in “real time” (as opposed to what? unreal time?) by a cast of obsessive individuals. The prequel to the L.A. Quartet, with most of the usual suspects. And a welcome return after Ellroy’s exasperating sojourn into gangsterland. It’s now December 1941, before, during, and after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Unavoidably political, with echoes of 9/11. As usual, the psychogeography (with an emphasis on psycho) of LA figures heavily. Forget the self-mythologizing, the Dog is nearly back on form, with fodder for three books to come. Can’t wait, even if, for me, this one, with its often poetic pulp prose, runs out of steam on the final lap. But, for Ellroy, it’s less about resolution than the process that gets you there.

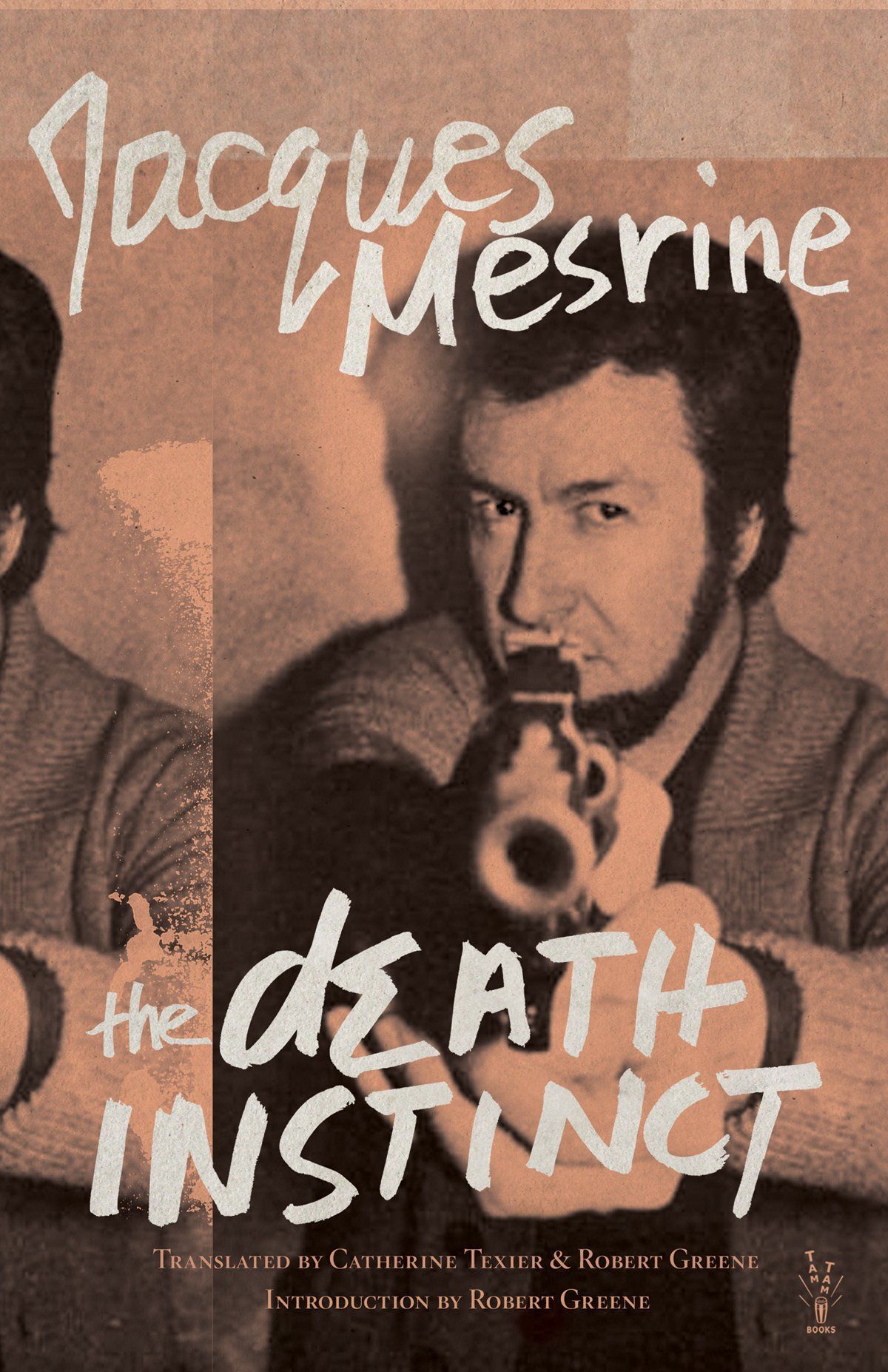

The Death Instinct by Jacques Mesrine (Tam Tam)

If Richet-Cassel’s film seemed enticing, Mesrine’s true crime memoir will give you a new appreciation for the criminal class. This is the inside scoop when it comes to master criminal and escape artist, a man not only of many disguises but bank robber extraordinaire, and the equal of any crime writer when so far as getting it all down on paper. Read this and you’ll understand why Mesrine was a hero, or antihero, to an entire generation of Situationists and les soixante-huitards. Mesrine claims never to have killed an innocent person. That’s more than you can say about most political leaders. And you can be sure, if he were alive, he’d know how to deal with those pesky banksters. From Tosh Berman’s stupendous Vian-oriented Tam Tam books.

Brainquake by Samuel Fuller (Hard Case Crime)

Fuller was not only one of our great directors, he was also a formidable novelist (144 Piccadilly, The Big Red One, Dark Page, et cetera), creating tabloid fiction as powerful as his films. Written during the 1980s in Paris where Fuller had exiled himself after the White Dog debacle. Incredibly, this is Brainquake’s first English publication, though it appeared in France some 20 years ago. Yet another example of Fuller as muckraker, observer, storyteller, and absurdist, it moves from New York to Paris, filled with surprises, as the author juggles points of view and characters — a bagman with a brain disorder, a duplicitous girlfriend, and a world turned upside down — as if trying to fight his way into his own brand of noir modernism. Too bad Fuller never got around to adapting it for the screen.

Half World by Scott O’Connor (Simon & Schuster)

Covert action, the identity breakdown, voyeurism, paranoia, brainwashing: what more could you ask for? In fact, one wonders why there haven’t been more novels about the CIA-run 1950s–1970s mind-control program, in which unsuspecting subjects in San Francisco and elsewhere were given LSD to break down their personalities. With the disappearance of official documents, O’Connor fills in the gaps in this story that continues to haunt the culture. Here a Company analyst, Henry March, moves to the coast with his family, his assignment to conduct the aforementioned mind-bending experiments. Personality disorders, side effects, and contact highs ensue. A couple decades later, a drug-addled agent is sent to Los Angeles to infiltrate a group of political bank robbers who claimed to have been brainwashed by the CIA. And still everyone’s on the lookout for Henry March. In the end, it comes across like nothing less than a well-ordered P.K. Dick novel, and that’s no bad thing.

There Ain’t No Justice by James Curtis (Jonathan Cape)

Curtis (1907–1977) is responsible for such London working class classics as The Gilt Kid and They Drive By Night. Originally published in 1937, There Ain’t No Justice uses boxing, and its effect on a kid from the slums of Notting Hill, to explore social life and the underworld in prewar London. As usual, Curtis’s characters unashamedly deploy the language, syntax, and slang of their class. In lesser hands, this might have been a clumsy, cliché-ridden effort, but here it sounds exactly right, and more astute than Pen Tennyson’s 1939 screen adaptation. Curtis hung out in Soho watering holes with the likes of Gerald Kersh and Robert Westerby, as well as an assortment of poets and painters. If you’re into bleak, prewar, London novels, you won’t be disappointed by this one.

A Spy Among Friends by Ben Macintyre (Crown)

About spy and proverbial toff — British public school, Cambridge, et cetera — Kim Philby and, to a slightly lesser extent, his associate and eventual adversary, fellow toff Nicholas Elliott. Add to that mix Philby’s other friend and nemesis, US spook, poet, and CIA architect James Jesus Angleton. Macintyre’s fast-paced book begins with Philby’s and Elliott’s childhood and education and ends with Philby’s July 1963 defection to the USSR. A true crime tale that reads like a John le Carré novel. In fact, le Carré contributes an illuminating afterward — illuminating not so much about Philby as about le Carré’s assignation with Elliott. This is a book about class, the old boys network, and the British establishment, the remnants of which are still with us, though the current UK Bullingdon Club government are sloppy amateurs in comparison.

Of Cops and Robbers by Mike Nicol (Old Street)

A Cape Town–set novel that, in switching between the past and present, demonstrates that corruption, greed, and violence follow no color or party line. Opening with a cack-handed theft of rhino horns from a Cape Town museum, then moving to a variety of characters representing different segments of South African society, including a blond surfer-investigator like someone out of a Don Winslow novel, and his girlfriend, a mixed-race lawyer with a gambling problem. Together, they come up against the powerful, and those, including an Apartheid era death squad, who do their bidding. Clearly, in the new South Africa, with its racial mix and past, it isn’t easy to distinguish the cops from the robbers, while multiple traces of the past inevitably linger. As well as having written a handful of crime novels, Nicol was responsible for Mandela’s official biography and A Good Looking Corpse, on the influential township-oriented Drum magazine.

Darkness, Darkness by John Harvey (Pegasus)

The world-weary, jazz-loving Nottingham copper Charlie Resnick is back, tracking down a case with origins in the UK’s 1980s miners’ strike. This is one of the always-interesting Harvey’s best, mixing, as it does, the personal and the political. If, as advertised, this really is Resnick’s final appearance, he goes out, after some three decades traipsing across the mean streets of Nottingham, in style. Harvey’s Darkness, Darkness, like Nicol’s novel, switches between the present — Thatcher has only recently keeled over at the Ritz — and the past. A heartfelt portrait of the East Midlands then and now, it’s further evidence of not only how the past affects the present, but how the present demands a revision of the past.

Goodis: A Life in Black and White by Philippe Garnier (Black Pool Productions)

I know, it’s a biography, but, nevertheless, an essential book for any noir enthusiast. It’s more than 30 years since the French edition of Garnier’s groundbreaking book David Goodis: La Vie en Noir et Blanc first appeared. Finally, thanks to noir supremo Eddie Muller, we have an English edition, translated by Garnier himself. But to say it’s a strict translation of the original would be somewhat misleading. Garnier has made more than a few alterations, adapting it for an American readership, which means he’s added some bits and taken away others. Nevertheless, the essential information remains intact; likewise, the function and drift of Garnier’s narrative, making it, along with Polito on Thompson, Sallis on Himes, and Freeman on Chandler, one of the best studies yet of a hardboiled writer.

The Mad and the Bad by Jean-Patrick Manchette (NYRB Classics)

Anything by Manchette is bound to be on my list of favorites. This is an early novel, first published in France in 1972. Maybe not his best, but still a cut above most novels published this or any year. Occasional architect Michel Hartog has morphed into a powerful businessman and philanthropist. Since the death of his brother in an accident, Michel’s fortune has mysteriously grown. Meanwhile, his orphaned nephew Peter is a spoiled brat. Michel hires Julie, straight out of the loony bin, to look after Peter, then hires a hitman to kill them both. Naturally, it all goes wrong. Manchette, writing as always in the white heat of cool, creates a narrative meant to lay bare society’s contradictions and hypocrisy, not to mention the everyday habits of the bourgeoisie. Fast-paced, with its fair share of violence, this is noir at writing degree zero from France’s finest exponent of the genre.

Futures by John Barker (PM Press)

Written two decades ago, and published in France in 2001, this is its first appearance in an English edition. And it’s every bit as, if not more, relevant today. A Londoner, Barker, a one-time member of the legendary Angry Brigade who has done more than his fair share of porridge, lays into the financial class with a vengeance. Here he takes the reader back to where it all went wrong, namely the Thatcher era and its deregulation of the financial sector. In doing so he compares the world of high finance with the economics of small-time cocaine dealing, as Carol, a coke dealer with a daughter to support, gets involved in a scheme entailing financial analysts, cocaine futures, the “Black Monday” stock market crash, and a hurricane that is sweeping through London. Intelligently written, it’s what happens when worlds collide.

Bubbling under the list:

Chance by Kem Nunn (Scribner)

Not his usual surf-noir fare, but, set in San Francisco, this novel focuses on a neuropsychiatrist, Chance, a high achiever from a wealthy family whose life is unraveling all around him. About to be divorced, he’s got problems with his daughter and his practice has hit the skids, with most of his income deriving from appearances in court as an expert witness. Unfortunately, he falls for one of his few patients, a woman with multiple personalities who’s married to a violent and corrupt cop. Chance needs help and has it thrust upon him in the guise of an overgrown psychopathic vigilante-type whose sleeplessness gives him that extra edge. Flawed — perhaps the result of excessive TV work (Deadwood, Sons of Anarchy). On the other hand, if it’s Nunn it can’t be bad.

Third Rail by Rory Flynn (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

With its corrupt Boston politicians and insidious mobsters, this high-octane thriller reads like a cross between Jack O’Connell and Andrew Coburn. “Harvard cop” Eddy Harkness’s observational skills and power of deduction might be second to none, giving him the inside line when it comes to finding money, corpses, drugs, and firearms, but fail to prevent the World Series death of a young Red Sox fan. For which Harkness is put to pasture, emptying parking meters in a nearby suburb. Hopes of re-establishing his career and reputation receive a setback when, after a night drinking, he loses his trusty Glock. In trying to retrieve it, he discovers a new addictive and delusion-enhancing drug has hit the streets. Flynn being a nom de plume for Stona Fitch, who, in his non-Boston-Irish guise penned the brilliant Senseless and Give+Take.

The Getaway Car by Donald Westlake, edited by Levi Stahl (University of Chicago Press)

Not a novel, but a collection of Westlake ephemera. You don’t have to have read the great man’s entire oeuvre to be charmed by this volume, though obviously some familiarity will help. Among its far-ranging nonfiction contents are essays, short and long, on the likes of Peter Rabe, Charles Willeford, Rex Stout, and Jim Thompson, a fragment of an autobiography, book intros, interviews, letters, and, believe it or not, some recipes. And throughout it all is Westlake’s self-deprecating humor, demonstrated most obviously in “Hearing Voices in My Head,” a tongue-in-cheek panel discussion with Westlake and his various pen personalities — Richard Stark, Tucker Coe, and Timothy J. Culver — which soon descends into chaos.

North Beach Girl/Scandal On the Sand by John Trinian (Stark House Press)

Born in Salinas, in 1933, Trinian settled in the Bay area, supplementing his writing in the 1950s by working as a bartender in a Sausalito waterhole, reminiscent of a character in a Don Carpenter novel. Trinian had quite a reputation at the time, not all of it laudatory. Pulp pundit Rick Ollerman calls him “one of the most realistic of the Gold Medal writers.” Indeed, both North Beach Girl (1960) and his final Gold Medal novel Scandal on the Sand (1964) read like minor classics. Included in this volume are essays by Ollerman, Trinian’s daughter (the artist Belle Marko), and his former partner, the novelist (and in later years, wife of Bonzo Dogger Vivian Stanshall) Ki Longfellow.

The Whitehall Mandarin by Edward Wilson (Arcadia Books)

A complex, well-researched spy novel featuring a cast of spooks, as well as Lady Penelope Somers, head of the UK’s Ministry of Defense. It moves rapidly through the Cold War years, including the Profumo affair, the Bay of Pigs, Malaya, Vietnam, and China’s growing importance. Granted, it takes some suspension of disbelief, if only because so many events of earthshaking importance are included. But with enough real personalities to keep the reader googling until the spies come home. Wilson was an American Special Forces Officer in Vietnam, who, after the war, moved to England and renounced his US citizenship. Not quite up to, but not far off, the likes of Ambler, Furst, McCarry, and le Carré.

¤

Woody Haut is the author, most recently, of Cry For a Nickel, Die For a Dime.

LARB Contributor

Raised in Pasadena, but now living in London, Woody Haut is the author of Pulp Culture: Hardboiled Fiction and the Cold War; Neon Noir: Contemporary American Crime Fiction; Heartbreak and Vine: The Fate of Hardboiled Writers in Hollywood; and of the novels Cry For a Nickel, Die For a Dime and Days of Smoke.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Tom's Book Club: James Ellroy

Andrew Coburn: The Understated Noirist

Andrew Coburn writes the suburb’s voyeurs, misfits, the covetous, the deranged, and the eccentric.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!