Dignity Cannot Be Annexed

Jemimah Steinfeld presents excerpts from a compelling personal essay by Nariman Dzhelyal, a Crimean Tatar activist who is currently a political prisoner in Russian-occupied Crimea.

By Jemimah Steinfeld, Nariman DzhelyalMay 7, 2023

NARIMAN DZHELYAL IS a name we should all know. Dzhelyal is a Crimean Tatar—an ethnic Muslim minority indigenous to the Crimean Peninsula that has been on the receiving end of Vladimir Putin’s aggression since the occupation began in 2014. Members of the community and their supporters have faced countless cruelties: harassment, intimidation, threats, home searches, physical attacks, imprisonment, and enforced disappearances. Always standing in their corner and fighting against these cruelties has been Dzhelyal.

For this, Dzhelyal languishes in jail in Crimea, where he’s been since 2021. He was sentenced to 17 years on trumped-up charges of “sabotage,” and now, to make matters worse, authorities are threatening to move him somewhere remote. If this first deputy head of the Mejlis (a title best summarized as leader) gets lost in Russia’s penal system, the Crimean Tatars will be deprived of their most vocal advocate, and we too will be deprived of someone who boldly stands up to Putin’s tyranny.

I first heard Dzhelyal’s name last October when I had coffee with the Ukrainian writer Andrey Kurkov. A resident of Kyiv, Kurkov had a lot of things on his mind, but the plight of the Crimean Tatars seemed to fire him up the most. We kept in touch, and Kurkov later told me that Dzhelyal’s situation was getting desperate. He had written an essay from prison. Did I want to see it?

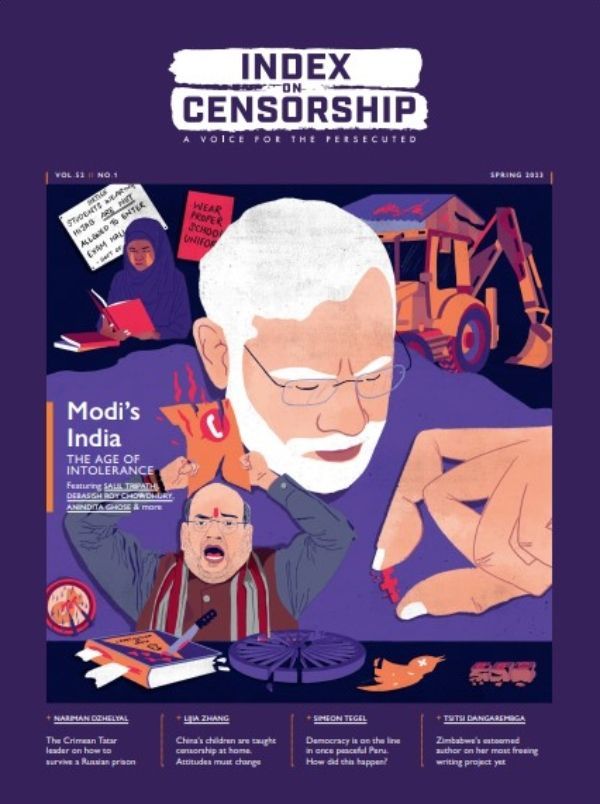

The quarterly magazine I edit, Index on Censorship, which focuses on challenges to free expression around the world, has worked with incarcerated dissidents since we debuted in 1972, and we often publish prison essays. The importance of such material cannot be overstated: it keeps a cause in the spotlight and ensures that those in prison know they’re not forgotten. And so, of course, I said I wanted to see the essay, and soon enough, thanks to Kurkov’s wife Elizabeth (a skilled translator), I had a copy in my hand.

The essay is remarkable. Dzhelyal has a clarity of mind that one would not expect from someone in such dire circumstances. Titled “Dignity Cannot Be Annexed,” the essay gives insight into Russia’s occupation of Crimea from the perspectives of those who are occupied and those doing the occupying (gleaned from conversations with prison guards as the author tries to understand their motivations). The tone is not self-pitying, though Dzhelyal would be forgiven if it were. Describing his current state, he draws comparisons with prisoners in Nazi concentration camps while still having the perspective and humility to say that his lot is not as bad.

As Dzhelyal emphasizes, we do not know what tomorrow brings, a fact he takes solace in. But if you would allow me to speculate for a moment, I would say that Dzhelyal is likely to be a future Václav Havel—the Czech playwright, essayist, and political prisoner who played an instrumental role in the Velvet Revolution and became the first president of an independent Czech Republic—a global statesman-in-waiting who will be integral in building a post-Putin order. It’s nothing short of a privilege that we could publish his essay (an excerpt from which appears below) in our spring 2023 issue, and nothing short of a travesty that these eloquent words were written in prison.

¤

“You were warned!” said a strong, rough voice.

A few hours after the search of my house and my arrest, I was sitting on a chair—handcuffed, with a bag over my head—in a basement, no one knows where.

“About what?”

“Not to go to the Crimean Platform.”

There it was! Finally, after a rather lengthy conversation about the gas pipeline explosion and my alleged participation in it, I finally heard the real reason for my arrest. Up to that point, the conversation had been so outlandish, the statements so far-fetched, that I kept waiting for the main point to be voiced.

My attendance at the international summit in Kyiv was certainly not the only reason for my arrest. But more on that later. It was necessary to go to the Crimean Platform, although the risk was higher that year than ever before. The Russian leadership reacted extremely sharply to this event. It was obvious that activists who dared to go from Crimea to Kyiv would attract some serious attention.

Of course, the platform would have taken place without us. The presence at the summit of a handful of people who had come directly from occupied Crimea—formal representatives of the occupied peninsula, living witnesses of what was happening there, participants in peaceful resistance—may have remained unappreciated then, but it would acquire significance later. The Kremlin was well aware of this significance and, therefore, did not want anyone to go. We were tailed until we had left Crimea. We were detained on the road, at the border checkpoint where we had a stilted conversation with the border guards.

No one directly said: “Don’t go! You’ll regret it!” But apparently, the six-hour grilling was the warning I was now being reminded about.

It didn’t stop me.

I had to go for another reason as well. Since 2014, fear had spread throughout Crimea. Using administrative, legislative, and informational methods, all residents of Crimea have been taught to refrain from any actions that are not sanctioned by the state, and under no circumstances to go beyond the limits of permitted behavior. As people succumb to these rigid taboos, they restrain themselves, construct barriers, and isolate themselves. Free civic activity, although it had not completely disappeared, had sharply declined, acquiring a sporadic and fragmented character.

It was impossible to remain indifferent to this process. People needed to see examples of different behavior. Providing such examples was dangerous in the conditions of occupation, but it could inspire hope.

Once, after listening to my friend’s emotional speech about his plans to liberate Crimea, it occurred to me that he might not be in time—that there may be no one to liberate. There will someday be very few people who value freedom and are willing to fight for it, who will continue to see the occupation of Crimea as illegal and will want it to end. Under the onslaught of propaganda and fear for their safety, they will not only submit to change; they will also change themselves.

Few realize that we have actually ended up in a prison, in a kind of concentration camp for the 21st century. Its fences are hidden, camouflaged by new schools, roads, bus stops, cranes towering over new building sites, etc. Yet it is a concentration camp with strict rules and cruel guards—where the loyal get treats and the disobedient are punished. In a concentration camp, the goal of the authorities is to turn everyone into a faceless, homogeneous mass, absorbing those who disagree or resist …

We went to the summit so that people could see that it is possible to overcome your fear, to act by your principles and beliefs.

Let cautious folk consider us fools!

¤

“While you were writing your posts on the internet and did not cross the line, no one touched you,” said the owner of the rough, strong voice, who talked to me immediately after my arrest.

He came to my room in the FSB [Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation] office where people under investigation are kept and demanded that I follow him. On the day of my detention, I heard only his voice. I immediately recognized it now. I did not know what place he occupied in the local hierarchy, but he spoke imposingly, with a sense of superiority. As in the first meeting, he tried to make me feel guilty.

“It was you who dragged the other guys into this story. You messed up their lives.” He meant the Akhtemov brothers, Asan and Aziz, who were arrested before me in the same case. According to the text of the accusation, I “recruited” them as saboteurs. Subjected to physical and psychological pressure, both of them “confessed” and made video-recorded statements that they probably read off a prompter.

This video was broadcast by propaganda TV channels. As soon as independent lawyers got through to them, however, they refused to testify and declared that they had been put under psychological and physical pressure.

The words of my interlocutor sounded unconvincing to me. Some of the actions that the investigation attributed to me I did not do at all. And those that I did were motivated by intent that was different from that attributed to me in the investigation.

I had been living on the edge, although it didn’t seem to me that I was asking for trouble. How many of my friends and colleagues “crossed the line” and were expelled from Crimea, fined, arrested, or even abducted? How many times had my friends and foes been surprised that I was still at large? Some rejoiced, others resented it.

The Crimean Platform had apparently become my “red line.” I don’t regret crossing it at all. However, I did feel that the criminal prosecution was aimed not only at isolating me and punishing me for my dissent and beliefs; my arrest was also aimed at intimidating everyone who shared my thoughts and acted as I did. What I could not understand was the accusation of sabotage. After all, sabotage did not fit in with my activities. The Kremlin had much more “convincing” grounds for my arrest—for example, membership in the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people, an organization that has been banned in Russia since 2016. Or my “calls” to violate the territorial integrity of the Russian Federation. I had said and done many things that had become punishable due to hasty changes to the criminal code made by the State Duma.

It would have been easier for the prosecution to find plausible evidence of those “crimes” since I did not hide my status and public position, and my posts, comments, and speeches at events were certainly recorded by authorities.

Of course, there is in fact no need to prove anything in these investigations. They are traditionally based on the testimony of classified witnesses. And the prosecutor and the judge will once again become accomplices in a crime—the custom-made incrimination of innocent people.

My interlocutor, although I did not understand the purpose of our conversation, was frank: “Do you understand that after your case, the issue of recognizing the Mejlis as a terrorist organization is likely to be raised?”

This revelation did not surprise me. A few hours earlier, my lawyers, Emine Avamileva and Nikolai Polozov, and I had already thought about this threat. The purpose of my arrest was now clear.

The logic was extremely simple. All “leaders of the Mejlis” had now become objects of criminal prosecution by the Russian authorities—Mustafa Dzhemilev, Refat Chubarov, Akhtem Chiygoz, Ilmi Umerov, and others. But the FSB needed something dirty, discrediting, for their plan. Directly linking the Crimean Tatars’ representative body with terrorist actions was just what they needed. Nobody would doubt that these people were inveterate terrorists and that the entire Crimean Tatar people were terrorists. Very soon, the use of the Crimean Tatar people’s symbols—the flag and the anthem—could become justification for a further round of political repression.

Naturally, the Russian authorities would try to use this “achievement” in the international arena as well, discrediting the Crimean Tatar people, their national movement, their representative bodies, leaders, and activists—their collective ideas and goals.

However, I know that Russia’s lies will not mislead anyone. No one will believe that the Crimean Tatar people, who for many decades have been waging an absolutely nonviolent struggle for their fundamental rights, could suddenly descend to primitive and dirty terrorism. No, the main purpose of this crime—the creation of a new big lie about the small group of Indigenous people of Crimea—is the repression of the peninsula itself, its population, and the Crimean Tatars.

To commit monstrous crimes—genocide, deportations—it is necessary to inflate political mythology. To justify the mass destruction of people and the creation of concentration camps, you have to come up with a terrible conspiracy of enemies of the people. You have to put the spotlight on a network of vigilant traitors, and you have to create theories of racial inferiority. In today’s Russia, a myth has formed about the total threat of terrorism, which has little in common with real global problems.

Crimea has turned into a concentration camp—a hybrid concentration camp, with the illusion of free life.

¤

Translated by Elizabeth Kourkov.

¤

Jemimah Steinfeld is the editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship.

LARB Contributors

Jemimah Steinfeld is the editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship, an award-winning quarterly themed around free expression. She is also a published author whose work has appeared in The Guardian, The Telegraph, and CNN, among many other venues.

Nariman Dzhelyal is a Crimean Tatar activist who is currently a political prisoner in Russian-occupied Crimea.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Prisoner

LARB presents excerpts from Vladimir Pereverzin’s memoir “The Prisoner: Seven Years Behind Bars in Putin’s Russia.”

The Soul of Post-Maidan Ukraine: On Andriy Lyubka’s “Carbide” and Oleg Sentsov’s “Life Went on Anyway: Stories”

Kate Tsurkan explores the post-Maidan prose of Andriy Lyubka and Oleg Sentsov.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!