Define Yourself: Riva Lehrer’s and Jan Grue’s Disability Memoirs

Goldie Goldbloom compares Riva Lehrer’s “Golem Girl” to Jan Grue’s “I Live a Life Like Yours” and explores their contributions to literature.

By Goldie GoldbloomJanuary 2, 2022

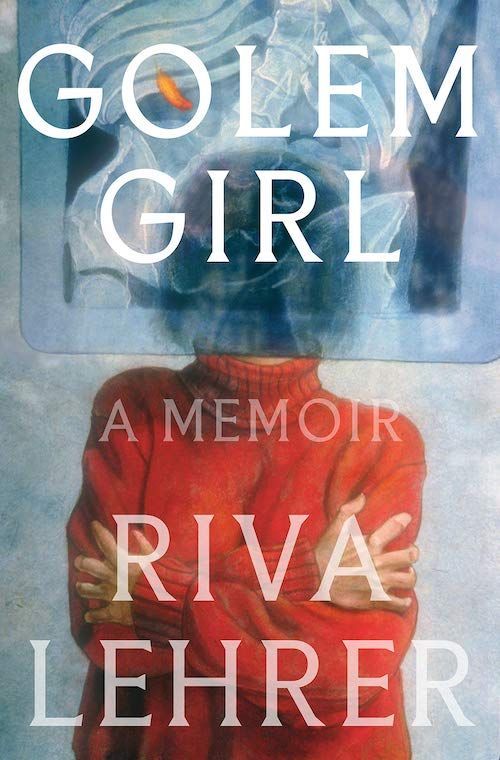

Golem Girl by Riva Lehrer. One World. 448 pages.

I Live a Life Like Yours by Jan Grue. FSG Originals. 272 pages.

GROWING UP, I used to go shopping with my sister, one of many chosen family members with disabilities who lived with us. She walked with the aid of sticks because a series of botched surgeries for spastic diplegia had left her paralyzed from the waist down. She was unable to push a grocery cart while simultaneously using her sticks. One day in the early 1980s, my sister’s crutch slipped in a puddle of water and she fell headfirst into a cabinet of frozen peas. We both roared with laughter as she of the incredible brain, the sophisticated sense of humor, the woman who had hoped to swim in the Arnhem Paralympics, mimed swimming through the veg. But when I asked for assistance in retrieving her from the freezer, management did not think it was funny. They did not like seeing a “person like that” doing the backstroke in their peas. They did not want to touch her. It took over half an hour for them to convince a police officer to lift her out. Though I had many times witnessed the way non-disabled strangers stared at my sisters, this was the first time I knew that behind that unholy gaze wasn’t just a curiosity born of ignorance. Behind the gaze was a powerful, inexplicable fear.

This, the way the disabled are viewed, is a painful refrain running through Riva Lehrer’s Golem Girl, recently released in paperback from One World, and in Jan Grue’s I Live a Life Like Yours, published by FSG in August 2021. In other ways, the memoirs couldn’t be more different: Lehrer’s book is ebullient, often comedic, saturated with specifics, printed on thick weighted paper with a hand-sewn spine, and liberally illuminated with her paintings and personal photographs. It documents in meticulous detail the life of the author: a well-known portrait artist, a professor, a disability activist, and one of the older survivors of spina bifida. Grue’s book is a slim paperback of sparse, wrenching prose, more Anne Carson than Proust. Even after finishing the book, I was unsure of Grue’s diagnosis, other than to say that he was originally diagnosed with muscular atrophy but now has been rediagnosed with something that causes widespread but not degenerative muscular weakness. (The author’s identity is similarly less public than Lehrer’s; I wasn’t sure of his position at the university either and looked it up online for this review, then had to use a magnifying glass to see the single tiny photograph of the author on the back cover.)

Early on, Grue quotes disability activist Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, saying, “The struggle for starees is how to look back.” This struggle to respond to the abled gaze is at the heart of both of these excellent additions to the slim roster of disability literature. In Golem Girl, Lehrer tackles the public’s underlying fear from the beginning: “I am a golem, a monster, a construct. Look at me! There’s nothing to be afraid of.” Being seen, for her, means displaying her diversity, the ways in which she has been taken apart and sewn back together again. She documents the way she grabbed life by the tail from the time she was an infant. Grue rejects that style of describing his experience and instead responds, in his aptly titled I Live a Life Like Yours, “Inside, I am just like you. Don’t judge me by my exterior!” His road to being seen focuses on the ways in which a disabled person is just like everyone else on the inside, what has been defined as inclusivity. He wants to love and be loved. He wants a family. He wants an education and respect. That wheelchair? It’s only a postscript to the man himself.

In published interviews, Lehrer states that for many, disability is performative. Being stared at all the time tends to cause the disabled to perform themselves in public as a coping mechanism. Like in a play or a film script, many of Lehrer’s adventures in school, with family, or with lovers open with a description of the clothes that were worn by the participants. Inevitably, Lehrer is wearing a dramatic costume, even as a two-year-old trying to wow her doctors. Her self-portraits, the ones that aren’t nudes, are full of glamorous clothing in bright colors, and her orthopaedic boots have glittering shoelaces. Her mother convinces a teenage Lehrer to agree to a major surgery by bribing her with a pair of sandals. As Lehrer says, “Even if I wear muted clothing, I still get stared at and I look shitty.” She’s not oblivious to the gaze. She knows she is being stared at and refuses to pretend otherwise. She sees your $20 and raises you $2,000.

Grue seems to struggle with how he wishes to be seen or how he sees himself. His memoir does not adhere to a linear timeline and instead follows a series of memories and philosophical ruminations circling a single idea: Who am I? The narrative coalesces around his old medical records and letters; the poetry of Mark O’Brien; discussions with doctors and family members; and his own wishes, dreams, and thoughts. He does not write chronologically because he does not wish to write “a version of himself that no longer exists.” The past is “a projected image, a show of light and shadow.” Throughout much of the book, there is a sense of veiling and cool remove. When he does slow down and focus sufficiently to allow the reader to see his morning routine, or what it takes for him to exit a chair or hold his child, the transition between the speed and agility of his mind and the excruciating slowness and precision of his physical movements is stunning.

It is only in these glimpses that the reader has a sense of how Grue returns the stares of his readers. The most wrenching of these scenes takes place on the night his wife goes into prodromal labor with their first child. Due to the weight and size of his wheelchair, Grue cannot get into the taxi with his wife. He speeds through the dark and snowy streets of Oslo in his electric chair, trailing far behind the taxi, desperately hoping he will be present at the hospital for the birth of his son. He is utterly ferocious, determined, as powerful as a knight on a charging steed. He doesn’t allow himself a shred of self-pity, but instead, blazes with righteous indignation.

Perhaps because of Grue’s more complicated relationship with seeing and being seen, he describes avoiding disabled people at college and when he travels. He hated a camp he attended with other disabled children and felt that he wasn’t like them. Lehrer, who as a child attended Condon School for Handicapped Children in Cincinnati, is grateful, however, for finding “her people” when she was young. “I learned how to tell a good story,” she says. She learned how to perform being disabled from a cast of expert performers, all of whom had to convince their doctors and their teachers and the world that they were deserving of a chance at an ordinary life.

In many ways, neither Grue nor Lehrer is limited by outsiders’ definitions of their disabilities: the two are talented, intelligent, compassionate, and successful well beyond average. They have both far outlived their childhood doctors’ incorrect assessments of their life spans. Lehrer’s portraits have been acquired by the National Portrait Gallery and the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum. She teaches medical humanities at Northwestern University and portraiture at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Grue is a father, a husband, a former Fulbright scholar who now holds a prestigious professorship at the University of Oslo in the Department of Sociology and Human Geography. In their memoirs, however, these accolades are barely referenced. Instead, the focus is disability. The lives they write about are lives in which Lehrer can’t get a wheelchair at the airport because non-disabled people are using them to get through security lines. Grue is told to stand up and walk several hundred feet to a plane, as his chair is deemed too wide to enter school buildings.

Paradoxically, though both Lehrer and Grue have been indelibly scarred by the unwanted gaze of the starees, they chose to write books about their lives. A book is inherently something that is viewed; a memoir is one more way of being stared at. It is not unusual when reading a memoir or autobiography to feel like a voyeur, and this is perhaps particularly true when the subject is part of a marginalized group in which the reader is not included. I struggled reading a book like Cheryl Strayed’s Wild, because of the private intimacy of certain moments, such as Strayed consuming her mother’s ashes — but I felt guilty reading Lehrer’s and Grue’s memoirs, as if I was somehow perpetrating yet more crimes against their privacy, even though I had been invited to do so by the authors. Maybe that is part of the point, of course: to force the reader into inhabiting the gaze. However, at the end of each book, I felt buoyed by the writers’ ability to demand that disabled people be viewed as individuals, each in the particular way they chose to be portrayed.

In an interview with Christine Sneed in Zyzzyva, Riva Lehrer said that the “one permanent change [she wishes she] could effect in representations of people living with disabilities” would be “demystification about who we are and how we live. Half the time outsiders believe our lives are tragic, when they’re just difficult.” To Judy Bolton-Fasman at Forward, she added that she wants “to make people look at variant bodies with pleasure or openness again.” Which is to say, she wants disability and disabled bodies to be seen as an ordinary part of the human continuum.

Unfortunately, people with disabilities, despite being the largest minority in the United States at something like 25 percent of the population, are woefully underrepresented. Though Lehrer’s astounding catalogue raisonné (found in the back of Golem Girl) includes 50 portraits of the visibly disabled, the two portraits purchased by national galleries are of the well-known writers Alison Bechdel and Achy Obejas. Ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and even socioeconomic status are the mainstays of representation politics. Discrimination due to disability and age remain largely hidden among the ashes, Cinderellas to the media. In the past and even today, the disabled and the elderly are often hidden at home or in institutions, out of sight of the public.

Grue says, “At some point or another I stopped thinking about myself as someone who needed repairing.” He learned to exist instead as someone who had already “become himself” in the world, free of the tragic narratives written by outsiders. Both Grue and Lehrer pose a powerful and universal question: Who are we capable of becoming if we refuse to allow ourselves to be defined by others?

¤

LARB Contributor

Goldie Goldbloom’s most recent novel, On Division, was awarded the 2021 Prix des Libraires, as well as the Association of Jewish Libraries Book of the Year. She has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Brown Foundation. Her first novel, The Paperbark Shoe, won the AWP Prize and was placed on the NEA Big Reads List. Her writing has appeared in Ploughshares, The Kenyon Review, and in many other fine journals. Goldbloom writes, edits, and teaches in Chicago. She is the mother of eight children.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Snow Angel

Dagoberto Gilb on surviving the epic power outage in Austin.

Both/And: A Conversation with Emily Rapp Black

Emily Rapp Black challenges cultural narratives on disability, memoir, and gender in this interview with Gina Frangello.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!