Controversial Contest

America’s signature women’s pageant changes –– slowly –– with the rest of the country.

By Elwood WatsonJanuary 30, 2021

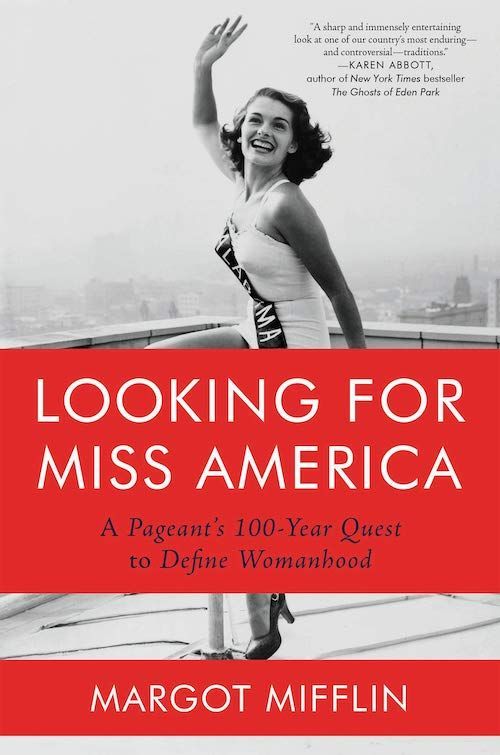

Looking for Miss America by Margot Mifflin. Counterpoint. 320 pages.

AFTER MONTHS OF INTENSE CONTROVERSY plaguing the Miss America Organization in 2018, Gretchen Carlson, Miss America 1989 and chairwoman of the governing body, announced that the nation’s most famous pageant for women would cease judging contestants on their physical appearance.

The pageant had grappled with this issue before — and punted. In 1995, viewers were invited to call in their votes to maintain or abolish the swimsuit competition. The vote ended with 80 percent of callers in favor of preserving the swimsuit competition.

Swimsuits aside, the fact is that the Miss America pageant has always been a locus of transformation. From its inception in 1921 to the present, the competition that overidealized femininity has earned admiration from many and intense disgust from others. As it moves into its centennial anniversary, it is an institution deeply endowed with a formidable amount of tenacity.

It has survived six years of cancellation (1928–’32 and 1934), the Great Depression, World War II, the second wave of feminism, the sexual revolution of the mid- to late 20th century, the Vanessa Williams nude photo scandal in 1984, increasingly low ratings for several decades, and the current #MeToo movement. But it is an institution that has managed to reincarnate itself with a remarkable degree of resiliency during its soon to be 100-year existence.

In her formidably researched book, Looking for Miss America: A Pageant’s 100-Year Quest to Define Womanhood, scholar Margot Mifflin provides a lavish and detailed account of the various milestones that have defined the pageant for decades. The chapters are divided into nine people-oriented categories: bathing beauties, dreamers, seekers, achievers, resisters, trailblazers, iconoclasts, believers, and survivors. The result is a spellbinding narrative replete with information about one of the nation’s more iconic events.

During the first decade of the pageant, scandals were as commonplace as the common cold: married women entering the pageant while hiding their rings, women falsifying their credentials, and barbs from religious groups — in particular, the Catholic Church, which saw beauty pageants as obscene. Others were inclined to believe rumors that young ladies from small towns were being corrupted by unscrupulous promoters and predatory men. Atlantic City, New Jersey, canceled the pageant for five years (1928–’32) and again in 1934, due to a combination of eroding financial support, the increasing belief among a growing segment of Americans that pageants were carnal in nature, and the onset of the Great Depression.

In 1935, the pageant tried to clean up its act by hiring Lenora Slaughter, a Southern White woman with years of experience in public relations. She helped add the notorious “rule number seven,” which stated that all contestants must be “of good health and of the White race.” This was abandoned in 1940, and Slaughter claimed amnesia when asked about it years later.

By 1955, the pageant hired singer and radio announcer Bert Parks to serve as emcee. With his folksy style, jovial antics, and down-home, engaging demeanor, he was enormously popular with viewers. It was during this period (1955–’70) that the pageant experienced its heyday. It consistently ranked among the top three programs. But as the times and the nation continued to evolve, the pageant found itself starkly at odds with much of the national sentiment. By the mid-1960s, the second wave of the feminist movement was in full force. It also guaranteed a clash of values, which arrived in visible fashion in 1968: more than 200 feminists descended upon the Atlantic City boardwalk — led by then-27-year-old Robin Morgan, who would later serve as editor of Ms. magazine — and threw curlers and girdles in trash cans, crowned a sheep, and fiercely voiced their opposition. That same year, Pepsi, a sponsor of the pageant, withdrew its support, stating: “Miss America as run today does not represent the changing values of our society.”

At the same time, many Black authors and cultural critics were examining the psychological, social, and emotional impact the pageant had on women of color. In 1970, Cheryl Browne, Miss Iowa, became the first Black woman to compete in the national pageant, breaking the way for future contestants and finalists. In September 1976, Deborah Lipford, Miss Delaware, made pageant history by becoming the first Black contestant to make the top 10. In the September 1980 pageant, two Black contestants, Lencola Sullivan, Miss Arkansas, and Doris Hayes, Miss Washington, made pageant history by winning preliminary awards. Sullivan cracked another barrier by being the first Black woman to make the top five, as she was fourth runner-up. During the September 1983 pageant, Vanessa Williams and Suzette Charles shattered another barrier and made history as they emerged as Miss America 1984 and first runner-up, respectively. Women of color continued to win the top honor, including Angela Perez Baraquio, an Asian woman from Hawaii who won Miss America 2001, and Nina Davuluri, who is of East Indian heritage and won Miss America 2014.

But these women, along with other contestants of color, faced racism from pageant fans who were resentful that a non-White woman was chosen as the representative of American beauty and womanhood. These are some of the book’s most riveting narratives. Mifflin shows the periodic moments of indecision that have plagued the pageant in lucid detail.

Yolande Betbeze Fox, Miss America 1951, is one of those many highlights. A product of the cotillion culture of the Deep South, she went on to study philosophy at the New School in New York City. After winning the crown, she refused to wear her swimsuit in public during her reign. Her defiance so angered the pageant’s swimwear sponsor, Catalina, that they parted company with the Miss America Pageant and created the alternative Miss USA and Miss Universe contests in 1952. Decades later, those pageants would eventually be purchased by Donald Trump. Betbeze Fox later became involved in the Civil Rights movement.

The first Black Miss America, Vanessa Williams, endured criticism both from racist Whites, who saw her win as an affront, and from some Blacks, who questioned whether her eye color, light skin, and brown hair made her “sufficiently Black.” Mifflin gives an intensely detailed description of Vanessa Williams’s selection as the pageant’s first Black Miss America and the backlash and racial fallout that followed. Mifflin’s perspective on the racial, cultural, and sexual stereotyping; the conspiracy theories; and on Williams’s resignation following the nude photograph scandal is deeply informative and compelling.

Beginning in 1989, pageant officials required all contestants to adopt a “personal platform” — a civic issue of personal interest that would demonstrate to the larger public that pageant contestants were socially conscious young women. But some platforms were more acceptable (and bland) than others. Miss America 1993, the late Leanza Cornett, adopted AIDS awareness as her platform, raising the blood pressure of the largely center/right-leaning pageant crowd. Her successor, Kimberly Aiken, Miss America 1994, took on homelessness for her cause. Kate Shindle, Miss America 1998, touted safe sex and condom distribution in public schools. This also sent segments of pageant-loving conservatives off the rails. Venus Ramey, Miss America 1944, attacked Shindle particularly strenuously in a revealing open letter that showed her own contempt for pageants: “All over the country, Miss Something-or-Others are using school podiums to enlighten our youth about the mysteries of sex,” she wrote,

[b]ut the real mystery is why administrators lend prestige to these charades. By their invitation to lecture on school premises, the principals and teachers tacitly intimate to students that young bathing-suit bimbos are cognizant of life’s intricacies.

Passions around the nontraditional sexual views of contestants had died down by the time Miss Missouri Erin O’Flaherty became the first open lesbian to compete in 2016. And this was two years before Deidre Downs, Miss America 2005, married her female partner in 2018.

Defining what the pageant represents is still up for debate. Is Miss America the girl next door? The sexy temptress slinking down the runway? The well-rounded Renaissance woman? A combination of all? Margot Mifflin’s Looking for Miss America: A Pageant’s 100-Year Quest to Define Womanhood is a fascinating and entertaining account for anyone interested in reading a first-rate analysis of the United States’s most distinctive beauty contest.

¤

LARB Contributor

Elwood Watson, PhD is a professor of history, African American studies, gender and sexuality studies, and popular culture. His book Keepin’ It Real: Essays on Race in Contemporary America was published by University of Chicago Press in 2019.

LARB Staff Recommendations

One Woman’s Century

Evan Pheiffer offers a portrait of his grandmother, Jayne, whose life spanned a tumultuous century.

"Never Have I Ever"...Seen Myself on TV

Linde Murugan considers Mindy Kaling's funny and frustrating take on religion, nationality, race, caste, and diasporic identity.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!