“Comrade, Can You Paint My Horse?” Soviet Kids’ Books Today

Ainsley Morse takes “The Fire Horse,” a collection of Soviet-era children’s poems translated by Eugene Ostashevsky, for a ride.

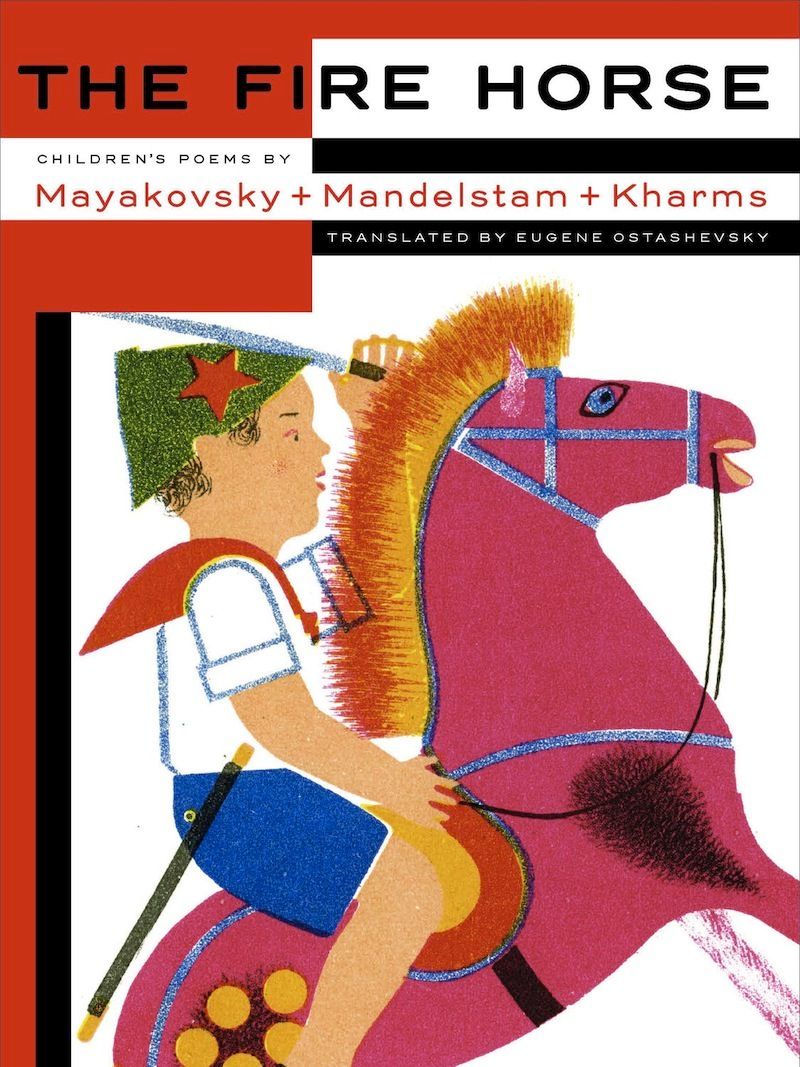

The Fire Horse by Eugene Ostashevsky. NYR Children’s Collection. 48 pages.

IF IT HAD LASTED, the Soviet Union would be celebrating its centenary this year — a “what if” that willy-nilly encourages thought experiments. The first 10 years or so of its existence are generally thought of as a happy time for the arts. Many avant-garde experimenters, whose aesthetic radicalism jibed nicely with political turmoil, emerged from obscurity to benefit from actual state sponsorship (imagine the Trump administration offering stipends to radically inclined artists right now!). And some of them offered their art, either wholeheartedly or with a certain calculation, “in service to the revolution.” In hindsight, it’s hard to observe this optimistic scene without wincing: all of these artists and writers getting cozy with the state machine that would shortly bring about their mental and physical destruction: imprisonment, exile, starvation, and suicide.

A lesser-known product of early Soviet support for the arts was the breathtaking flowering of Soviet children’s literature, as witnessed by NYRB’s The Fire Horse, with its faithful reproductions of three books from 1925 to 1930, translated and edited by Russian-American poet and critic Eugene Ostashevsky. Unsurprisingly, the new Soviet government was very interested in questions of child-rearing and education — building an entirely new world is easier with people who have only dim memories of the old one. The content and quality of children’s literature were seen as problems of revolutionary significance. Luckily, the people first entrusted to address them were writer-critics of great creativity and imagination, some of them chummy with the avant-garde. And yet, the story of children’s literature hardly has a fairy-tale ending (unless we have in mind a Grimm fairy tale). A lavishly illustrated collection of pictures from these books, Inside the Rainbow (Redstone Press, 2013), has an apt subtitle: Beautiful Books, Terrible Times.

Early children’s books by artists like Kazimir Malevich and El Lissitzky are masterpieces of abstraction, but don’t offer much by way of either ideology or pedagogy. As the 1920s wore on, though, children’s literature got pulled into bitter cultural debates — highlights include a major brouhaha over the fairy tale, seen either as innocuously accessible or heinously corruptive. By the time Vladimir Mayakovsky, Osip Mandelstam, and Daniil Kharms — the authors featured in The Fire Horse — came to children’s literature, it was more of a minefield than a playground. Moreover, as it transitioned from grand experiment into established industry, children’s literature began to attract writers less interested in forming the new homo sovieticus than in just scraping by on freelance honorariums.

Of the three writers featured in The Fire Horse, Mayakovsky had the most straightforward political motivations. A pioneering member of the pre-revolutionary Cubo-Futurists, he had scandalized bourgeois audiences with his loud staccato verses and infectious neo-Romantic poetic persona, a lovelorn pariah eager to topple idols and win hearts with unprecedented metaphors and facepaint. When the revolution hit, Mayakovsky became a foghorn for socialism. His children’s poems, of which the “The Fire Horse” is a prominent example, are transparently didactic (if not moralistic, as in the neatly titled “What is Good and What is Bad” [1925]). True to demands of the time, “The Fire Horse” demonstrates a proper ideological orientation: the child-hero wants to grow up to be a Soviet cavalryman, and his father is a worker. It also explains in detail how the horse is made, and at the cost of whose labor. Still, Mayakovsky’s style shines through even the densest material, and Ostashevsky’s translation marvelously captures its combination of sprightly rhythm and tautology:

Riding experts

have revealed

There’s no riding without the wheel.

“The Fire Horse” is gorgeously illustrated by the avant-garde artist Lidia Popova. Artists’ books with interdependent text and illustration were a mainstay of Futurist production before the 1917 revolution. Mayakovsky and his brash young comrades were aware of the similarities between their chapbooks and books for kids, all the more since many of them were strongly drawn to a primitive or childlike aesthetic. So it wasn’t much of a leap to start illustrating children’s books — even better if the author of the text also had avant-garde inclinations. In the case of Mayakovsky’s poem, Popova’s illustrations really save the day, helping the ideological message along with bright portraits of the individual workers. And images like the horse under construction at a crazy angle, swarming with busy workers, enliven sections of less inspired verse (“But the work keeps pressing forward: / They cut up a sheet of cardboard”).

Illustrations also take center stage in “Two Trams,” one of Osip Mandelstam’s few attempts at children’s literature. Mandelstam had made his name before the revolution as an Acmeist poet, a kind of Russian High Modernist, with intricately allusive poems full of strikingly beautiful music and densely concentrated images. The mid-1920s found him anxious, creatively frustrated, and chronically short of money — hence the turn to children’s poetry. In her memoirs, Mandelstam’s wife, Nadezhda, recalled that these poems did not come easily to her husband, and that his more successful pieces were written as funny little “occasional” verses, not specifically child-oriented: “Short little poems, like sayings or proverbs. You fry an egg — write a poem about it. Forgot to turn off the kitchen sink — write a poem…”

But “Two Trams” is a sweet and mournful little tale with a classic children’s literature plot — a kind of Are You My Mother? for public transportation. Click and Zam come across as ordinary, rather weary citizens:

Rattling and clattering over joints on the track

Gave Click a shattering platform-ache.

And Zam is characterized by his “stooped back and red platform.” While loyally searching for the temporarily disabled Click, he encounters all kinds of other vehicles and urban phenomena, illustrated with mobile abstraction against stark cityscapes. In contrast to Mayakovsky’s literalism, Mandelstam throws in metaphors with a (perhaps too) generous hand: a clock tower has “two lines [going] around a plate / Like a black mustachio”; trams are “clumsy as geese.” Ostashevsky shines in his renderings of the beautiful, often unmotivated wordplay:

But Zam spirk-sparks,

[…] He clangs clangier than anybody else.

“I will ask the horses, the horses,

If they saw an openmouthed tram pass,

Not a trim tram – a traipser, a doofus.”

A side note on Ender’s illustrations: While pleasingly symmetric, their flatness and starkness almost seem to work against the story line. Mandelstam’s poem strives to endow clanking, blinking trams with a kind of humble pathos, and freely anthropomorphizes everything it comes across — the “sweet street, mama of all trams,” the moustachioed clock-tower, and a glowering seven-story house. The illustrations, meanwhile, resolutely avoid faces (the few tiny human figures are literally faceless, outfitted with white orbs à la later Malevich); though there is a melancholy charm to the image of a tiny red tram doggedly seeking his cousin against the backdrop of a featureless high-rise.

The final selection in the book, Daniil Kharms’s “Play,” is the best children’s book qua children’s book. Kharms, a brilliant and tortured absurdist who liked to proclaim his hatred for children, remains one of Russia’s best-loved children’s poets. His poetry (for children and adults alike) has an immediately recognizable, driving physical rhythm, captured perfectly in Ostashevsky’s translation:

Peter ran down the road,

down the road

along the pavement,

Peter ran

along the pavement,

and he hollered

“Roo-roo-roo!”

According to the godfather of Soviet children’s poetry, the poet and translator Korney Chukovsky, the “tenth commandment of children’s poetry” was that it should optimally be written in trochees (BAM-bam BAM-bam), and another commandment was to avoid adjectives and favor verbs above all else. Ostashevsky’s Kharms fulfills both brilliantly in this passage:

jumping, skipping, hopping, springing

loudly shouting

“Zoo-zoo-zoo!”

Ostashevsky doesn’t struggle to jam the English into regular trochees, but he keeps the spirit of that meter, as well as the insistent repetition that produces a nearly cinematic immediacy of action and image. Poets, take note: Kharms’s fellow poets in the late avant-garde OBERIU circle also worked day jobs in children’s literature, and some of the tricks they learned writing for kids proved marvelously applicable in experimental “adult” poetry as well.

Published in 1930, “Play” is the latest of the three books featured in The Fire Horse, but its illustrations are curiously “old-fashioned.” Vladimir Konashevich had been illustrating children’s books since before the revolution, and his pictures — even with their stylized sketchiness and the modest village setting — evoke the more refined and elegant tastes of the pre-revolutionary intelligentsia. The poem, too, gestures minimally toward contemporary mores: the steamboat and airplane are occasionally qualified as “Soviet,” something that might be part of the boys’ imaginary game or might just have provided Kharms with a couple of missing syllables.

1930 was also the year Mayakovsky killed himself; Mandelstam would die in imprisonment and exile in the late ’30s, and Kharms starved to death in 1942, imprisoned in a psychiatric hospital in besieged Leningrad. I don’t think you have to talk to your kids about the authors’ wretched ends as you read them this book, but it’s hard to ignore the bright red star on the child-sized Red Army cap on the cover. Just as the boy wearing the cap follows all the steps it takes to make a hobbyhorse, we can trace the complicated yet uniformly tragic fates of virtually all the people involved in making these exquisite, politically fraught little books.

¤

LARB Contributor

Ainsley Morse is a literary translator and Russian literature scholar specializing in poetry and the 20th century.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Both a Fish and an Ichthyologist: On Viktor Shklovsky’s Diverse Achievement

Adrian Nathan West appreciates the diversity of “Viktor Shklovsky: A Reader” edited by Alexandra Berlina.

Pure Literature: On Herta Müller and Svetlana Alexievich

James Thomas Snyder considers the work of two Nobel laureates from Central and Eastern Europe, Herta Müller and Svetlana Alexievich.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!