Comping White

Laura B. McGrath looks at the data to find out why the publishing industry is still so white.

By Laura B. McGrathJanuary 21, 2019

ON NOVEMBER 9, Publishers Weekly broke the news that the publishing industry is overwhelmingly white — 86 percent white, to be exact.

Every year, Publishers Weekly (PW) releases its annual Salary Survey. Since 1994, the Survey has been circulated among industry professionals, who are asked to respond to demographic and opinion-based questions about their experience in publishing. True to its name, the Salary Survey reports on trends in compensation, wage gaps, and promotions. Since 2014, the Survey has focused on one particular problem: the staggering lack of diversity in the ranks of New York houses. The numbers are bleak, and suggest little change.

2014: 89 percent white

2015: 89 percent white

2016: 88 percent white

2017: 87 percent white

2018: 86 percent white

To their credit, PW acknowledges that the problem of representation in the workplace is also a literary problem. PW explained the connection in 2014: “The dearth of minority employees directly affects the types of books that are published, industry members agreed, and for this issue to be addressed, there needs to be more advocates for books involving people of color throughout the business.” Quite right. Yet, the problem is far more complicated, and far more entrenched, than the PW Salary Survey suggests. To be sure, these numbers are bad. But they are only one part of a large, institutional problem — a by-product of an industry that is discriminatory by design.

People of color are not only underrepresented on the payroll of publishing houses; they’re underrepresented throughout the literary world. And while the fact of their discrimination has been accepted anecdotally, it has yet to be thoroughly accounted for. In 2012, Roxane Gay responded to the annual VIDA “count” of Women in Media in an essay called “Where Things Stand”, arguing, “Race often gets lost in the gender conversation as if it’s an issue we’ll get to later. I’ve wondered about where race fits into the conversation and who will take up that issue with the same zeal VIDA has approached gender.” To date, no group or individual has taken up her challenge.

Instead, Publishers Weekly asks, in the 2016 Salary Survey: “Have strides been made in improving title diversity?” Strides — so flabby, undefined. It’s almost impossible to answer in the negative. The Salary Survey itself might well be credited with “making strides.” But does a three percent decrease in the number of white respondents count as a stride, or is it more of a stutter step?

One can imagine far more useful questions that would get us far more useful answers. How many books by writers of color are published annually? How many reviews are dedicated to books by writers of color? How many books feature people of color in a substantive manner (a sort of Bechdel test for racial diversity)? Counts like these could be extremely effective, because — here’s Gay, again — “when it comes to confronting inequities in representation, people want proof. They won’t just take your word that the sky is falling. They need to see the sky shattered, on the ground.”

So I set out to gather some proof.

¤

At the Stanford University Literary Lab, we use computational methods to study literary history on a large scale. I’m also writing a book that considers how the business practices of the Big Five have shaped contemporary fiction. All this is to say: The question of counting, and who counts, in literature is an important one to me.

To begin to tackle these questions, I turned to publishers’ seasonal catalogs, from 2013 up through the current 2019 season. These data come from the same span of time as the PW counts I was able to find online. Catalogs contain a wealth of information used to market books, from price to page length to blurbs to author Twitter handles. I studied Adult Catalogs, not YA or Children’s Literature (which seems to be doing much better on the diversity front, as Lee and Low and the Cooperative Children’s Book Center report). I also limited my study to fiction, not essay collections, memoirs, or biographies. In all, I extracted metadata about 10,220 new fiction releases. [1]

As I sifted through the data, it became immediately clear that most obvious fruit was not, in fact, low-hanging. Identifying author race in a dataset this large would be impossible for an individual researcher, and would likely take a team at the Lab months, at minimum. Even if we had access to the full text of all 10,000-plus books, we would likewise struggle to quantify “books involving people of color”: Involved how? How do we identify character race? Should secondary characters — or worse, racist caricatures — be counted in the same way as main characters? The questions multiply and multiply.

Instead, I decided to study the most important data that no one outside of publishing has ever heard of: Comp Titles. “Comps are king in this business,” an editor told me. (She works for a major house, and spoke under the condition of anonymity.) Comps, short for “comparable” or “comparative” titles, are the basis of all acquisitions. By predicting profits and losses, comps help editors determine if they should acquire a book or not. Comps are a sort of gatekeeper, determining what — and who — gets access to the marketplace.

The logic is straightforward: Book A (a new title) is similar to Book B (an already published title). Because Book B sold so many copies and made so much money, we can assume that Book A will also sell so many copies and make so much money. Based on these projections, editors determine if they should pre-empt, bid, or pass on a title, and how much they should pay in an author advance. Above all, comps are conservative. They manage expectations, and are designed to predict as safe a bet as possible. They are built on the idea that if it worked before, it will work again.

Comps are about books, but they’re also about writers. This seems too obvious a claim to make, but it’s an important one. Because sales figures are determined by the size of the potential audience, editors pay special attention to these hypothetical readers when selecting comps and acquiring new titles. One editor explained, “You get into the type of author that somebody is, and the type of audience that they're reaching more than you do content. And that is very voice-driven. […] There’s a limited number of readers for a book like that, and you kind of know who they are and what books those people are responding to.” The writer’s identity — their voice — matters significantly to editors because it needs to align with a particular audience. Comps are proof of that author-audience alignment.

And if there’s no comp to be found? If a book hasn’t ever “worked” because it hasn’t ever happened? If the target audience for a book isn’t considered big or significant enough to warrant the investment? “If you can’t find any comps,” one editor explained, grimacing, “It’s not a good sign.” While intended to be an instructive description (“this book is like that book”), some editors suggested that comps have become prescriptive (“this book should be like that book”) and restrictive (“…or we can’t publish it”).

Comps perpetuate the status quo, creating a rigid process of acquisition without much room for individual choice or advocacy. One problem with the PW Salary Survey is the tacit assumption that People = Publications. If there were more people of color working behind the scenes, the thinking goes, then there would be more books by and about people of color published. But this assumption reduces a systemic problem to an individual problem. It assumes that “minority employees,” or, more broadly, “advocates for books involving people of color” might simply choose to acquire, market, and sell more diverse books. And, quite simply, acquisitions don’t work this way. The system, more than any individual, reinforces discrimination.

Comp title data don’t show us the output of this system — they show us the system itself. Comps are the books that most frequently influence editors’ decisions about what to acquire, the books to which new titles are often compared, the books whose effects the industry longs to reproduce. In other words, comps are evidence of what the publishing industry values.

It turns out the industry values whiteness.

From 2013 to 2019, publishers identified 31,876 comps — about three comp titles for every new title published. I wanted to know which comps get cited most frequently (and, by extension, communicate high value), so I winnowed the list of 30,000-plus comp titles down to the top 50 most frequently used comps. Because many books have been cited as comps the same number of times, this list is actually comprised of 225 titles. I then worked with my undergraduate research assistant, Jonathan Morales, to research the race of each of the authors whose books are listed here.

The majority of these comps — these books used to justify decisions about who gets published — have been written by white authors. Nine books by people of color appear on this list, including N. K. Jemisin’s A Hundred Thousand Kingdoms, Celeste Ng’s Everything I Never Told You, We the Animals by Justin Torres, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah. Just nine out of 225 books.

Granted, in a dataset this large, these top 50 comps represent a very small, exceptional group — these comps are just .1 percent of the entire dataset. Zooming out to the top 500 comps (the top two percent of the dataset) is equally staggering: 478 of the top 500 comps have been written by white authors. Justin Torres is just one of three Latinx writers. Celeste Ng is one of eight Asian Writers. And N. K. Jemisin is one of 10 Black writers. Together, writers of color make up just four percent of the top two percent of the dataset.

Comps reveal a great deal about the diversity of publishing and the experience of people of color within it. These data should give us pause about any self-congratulatory “strides.” Comp titles show us which books and which authors publishers most value; they become a target at which editors, agents, and aspiring authors aim. The dearth of writers of color as frequent and influential comps — both within and across genres — shows that writers of color still do not enjoy a broad influence behind the scenes. They don’t seem to be shaping acquisitions decisions at a high level. Even best-selling novels by writers of color are highly unlikely to change the decisions that publishers make about which books to acquire and by whom.

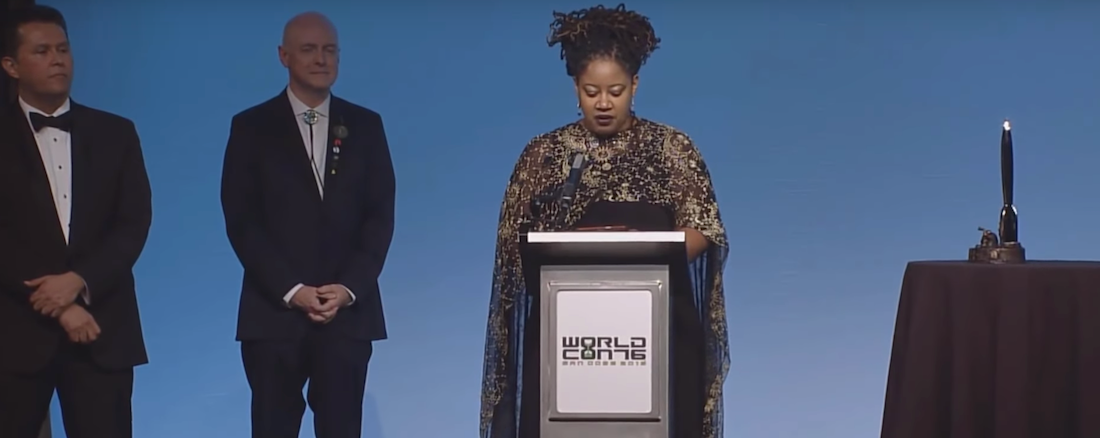

But these numbers shouldn’t surprise us. Writers of color have long spoken and written about their experiences of discrimination in the publishing industry, but we — and here, I indict my fellow white readers and writers — haven’t listened. Or we’ve dismissed their stories as “just one person’s experience.” These data show how those experiences fit within a larger system. Take N. K. Jemisin’s 2018 Hugo acceptance speech. Jemisin explained all of the difficulties that she faced in the historically white genre of science fiction: “I have kept writing even though my first novel, The Killing Moon, was initially rejected on the assumption that only black people would ever possibly want to read the work of a black writer.” In other words, editors couldn’t find the comps. They could not envision an audience that would make Jemisin’s work profitable and justify their investment in her first novel. We can, and should, commend Jemisin on her determination and talent. But it is a mistake to understand her searing speech as simply a story of a determined writer who overcame rejection — it’s also the story of a system hell-bent on keeping her out. Not incidentally, these are the exact sorts of systems that Jemisin’s novels challenge.

Some might read Jemisin’s presence on the top 50 list as evidence of meritocracy at work. Jemisin has earned many accolades since her first days of rejection — comps must work, assuring that the system honors and promotes the best of the best! But “meritocracy” cannot explain notable absences of people of color. Despite the substantial critical acclaim awarded to both Salvage the Bones and Sing, Unburied, Sing, Jesmyn Ward didn’t make the cut. Neither did Colson Whitehead, Min Jin Lee, Mohsin Hamid, Alexander Chee, or any number of brilliant writers of color. Perhaps editors would protest: these books aren’t good comps! And perhaps they aren’t. They might be too literary, or appeal to too small an audience. Or, perhaps they aren’t “universal” enough — which, in Jemisin’s words — “mostly just means ‘the ability to write something that appeals to white readers.’”

Even if acquisitions were a meritocratic system, the system is surely stacked against writers of color if N. K. Jemisin is the standard for inclusion. Jemisin is exceptional, on all counts. She was the first person to have won the Hugo Award three years in a row, for each book in a trilogy. The only person. Full stop. (And she endured Gamergate levels of harassment in the process.) This is a near-unattainable goal for any writer, let alone a writer of color. Meanwhile, the majority of books by white writers in the top 50, including those that outrank Jemisin, are entirely forgettable — neither best sellers nor award winners. Likewise, white writers can churn out book after book in a trendy series (for example, James Patterson’s Alex Cross). They can publish three or four novels before their breakout (The Middlesteins was Jami Attenberg’s fourth book). Jemisin is exceptional on all counts: she is an exceptional writer, and an exception to the rules of publishing that prize white writers for white audiences.

“Universality,” or appealing to white readers, seems to matter a great deal in this dataset. Consider, for instance Everything I Never Told You. Written by Celeste Ng, who identifies as Chinese American, the novel is ranked the 34th most frequent comp, the second-highest-ranking book by a person of color. Ng has written extensively about her experience as a Chinese-American woman in publishing, including an essay entitled “Why I Don’t Want to Be the Next Amy Tan.” Ng argues that the comparisons made between authors of the same race imply “that we’re all telling the same story,” which is “first and foremost A Story About Being Chinese, not stories about families, love, loss, or universal human experience.” Again, this might be read as a positive outcome, a more inclusive redefinition of universality. The data tell a different story. When Everything I Never Told You was initially acquired, it was not, in fact, compared to The Joy Luck Club. Instead, publishers identified The Yonahlossee Riding Camp for Girls by Anton DiSclafani, Bent Road by Lori Roy, and Reconstructing Amelia by Kimberly McCreight as suitable comps. Other books about mothers of teenagers and missing girls. Ng’s second novel, Little Fires Everywhere, was comped to novels by Lauren Groff, Liane Moriarty, and Emmas Straub and Cline. As far as publishers were concerned, Ng was not going to be the Next Amy Tan; she was going to be the Next Reese Witherspoon Adaptation.

I’ll admit, comp title data might not produce the same sort of sky-shattering effect that a total “count” might. Comps may be too complicated a data point, the system of acquisitions too convoluted. Despite the complexity of the system and the dataset, the conclusion is actually quite simple. The data suggest that there are two options available for writers of color within this system, neither of which is equitable or promising: beat the odds, or comp white.

¤

If, during the second week of November, you were watching the results of the National Book Award instead of the Publishers Weekly Salary Survey, you were treated to a different story about race and publishing in the United States. Not a different story, really, but a more complicated one. You would have seen a very representative group on the shortlist: Lauren Groff, Jamel Brinkley, Rebecca Makkai, Brandon Hobson, and Sigrid Nunez (whose novel The Friend was awarded the prize). For three years running, the National Book Award for Fiction has been awarded to a writer of color (Jesmyn Ward, Colson Whitehead, now Nunez). You would have learned about the National Book Foundation’s 5 Under 35, an equally diverse set of promising writers. You would have seen Isabel Allende win a Lifetime Achievement Award. Some critics have looked to the recent intentional diversification efforts of the National Book Awards as a sign that we no longer need to care about diversity in publishing because the problem has been fixed, as evidence of “overcorrection” and acquiescence to “PC culture,” or, at the very least, that people of color stand a good a chance as anybody to be successful in the industry. And that’s simply false. By design, literary awards are not a representative sample; they are exemplary. As such, they are hardly a bellwether for the marketplace.

Comps tell us a different story — a story of value and influence, of unreasonable expectations, and systems of exclusion. Not every writer will be fortunate enough to be published, let alone nominated for a major literary prize. But every writer, no matter their skill or success, will watch as their book’s acquisition, advance, and advertising is determined by comp. Of course, publishing was discriminatory long before such data-driven acquisitions were a common practice. But comps codify the discrimination that writers of color have long faced, perpetuating institutional racism through prescription: this should be like that — if you want to be published — if you want to be well paid. Whether or not comps cause discrimination in the industry, they certainly help keep books white.

¤

Laura B. McGrath is associate director of the Stanford University Literary Lab.

¤

Banner image from N. K. Jemisin's 2018 Hugo Acceptance Speech.

¤

[1] My thanks to Ross Ewald, Ryan Heuser, and Jonathan Morales for assistance with data scraping and wrangling.

LARB Contributor

Laura B. McGrath is an assistant professor of English at Temple University.

LARB Staff Recommendations

It’s Up to Us: A Roundtable Discussion

Kellye Garrett interviews Walter Mosley, Barbara Neely, Gar Anthony Haywood, Kyra Davis, and Rachel Howzell Hall.

The Craft Is All the Same: A Conversation with Victor LaValle

Ayize Jama-Everett interviews Victor LaValle about horror and diversity.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!