Collecting and Correcting

Martin Parr and Gerry Badger don’t discuss art, but rather they reevaluate what is and isn’t worthy of attention, whether it’s art or not.

By Geoff NicholsonApril 26, 2014

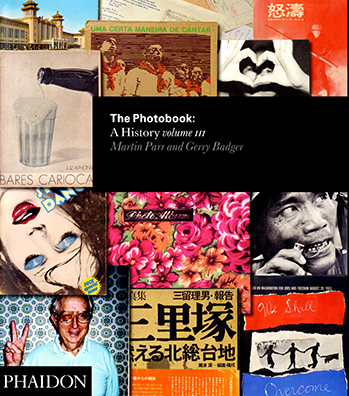

The Photobook: A History Volume III by Gerry Badger and Martin Parr. Phaidon. 320 pages.

I ONCE TALKED with a very rich collector who said he hated going to public museums and art galleries because nothing there was for sale. He wanted, and in many cases could afford, to buy the exhibits on display, and the fact that he wasn’t allowed to caused him endless frustration.

I often have the reverse experience when reading Martin Parr and Gerry Badger’s The Photobook: A History, the third volume of which is newly published. Together the books form a vast overview of photographic endeavors, as they have appeared in book form, covering a thousand or so titles. The reader is given a written description of individual books and their significance, along with a few images of the book itself, usually the cover and a couple of internal spreads. The dimensions of these reproductions vary, from half page down to the postage-stamp size.

The result is a catalog of a sort. Some (though by no means all) of the books included can indeed be bought from dealers, but the really good stuff comes at prices that make me swoon. In such cases these are books that will be owned by collectors with very deep pockets. In many cases the rest of us will never even see them, and certainly never touch them, turn the pages, smell them, have the crucial hands-on, physical experience that comes from a photobook. Did I mention frustration?

The introduction to the third volume says that the authors only conceived of a two-volume work, roughly chronological. The earliest book listed in volume one was Anna Atkins's Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions (1843-53); the most recently published in volume two came from 2005, Stephen Gill’s Hackney Wick and Jules Spinatsch Temporary Discomfort: Chapter I –V.

However, the project was always partly one of research, a quest to find undiscovered and unknown gems, and in doing so to create a revisionist history of photography. Much has evidently been discovered in the eight years since the second volume was published.

One of the most startling finds is a Japanese work titled Ginza Kaiwai/Ginza Haccho, which contains a foldout photographic panorama by Yoshikatsu Kanno, showing the buildings on both sides of a street in the Ginza district of Tokyo. It dates from 1954, 12 years before Ed Ruscha’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip did something very similar indeed in Los Angeles. If Ruscha knew the Japanese version, he’s not saying. Gerry Badger writes, “There is one important difference between the two. Ruscha’s was a ‘throwaway.’ Ginza Haccho is presented using all the panoply of fine Japanese book making.” Leaving aside the matter of just how many copies of Ruscha’s book were ever really thrown away, the market has in any case created a curious leveling off of value, or at least of price. Abebooks indicates that the committed collector can buy Ginza Haccho for about $11,000; a signed Every Building on the Sunset Strip runs about $8,000.

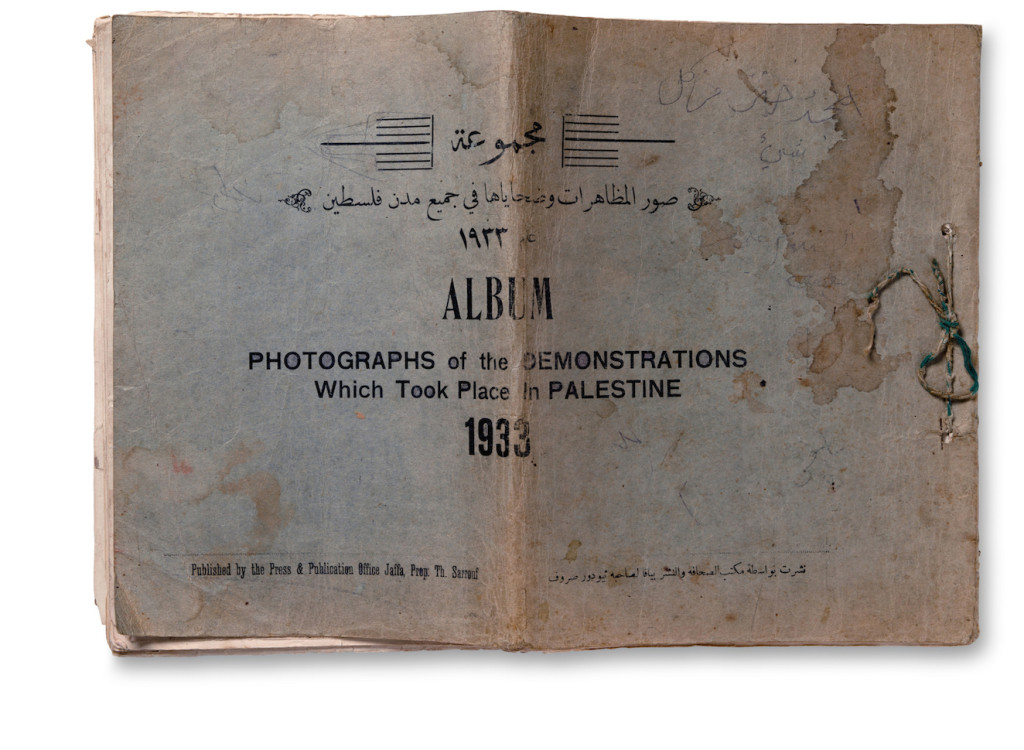

Some of the discoveries belong to history and politics as much as to photography. The book is divided into nine chapters with titles that include “Documents of Anger and Sadness,” “Killing Fields,” “Momenti Mori,” and “Cannibalizing Photography,” though none of these titles represents a watertight category.

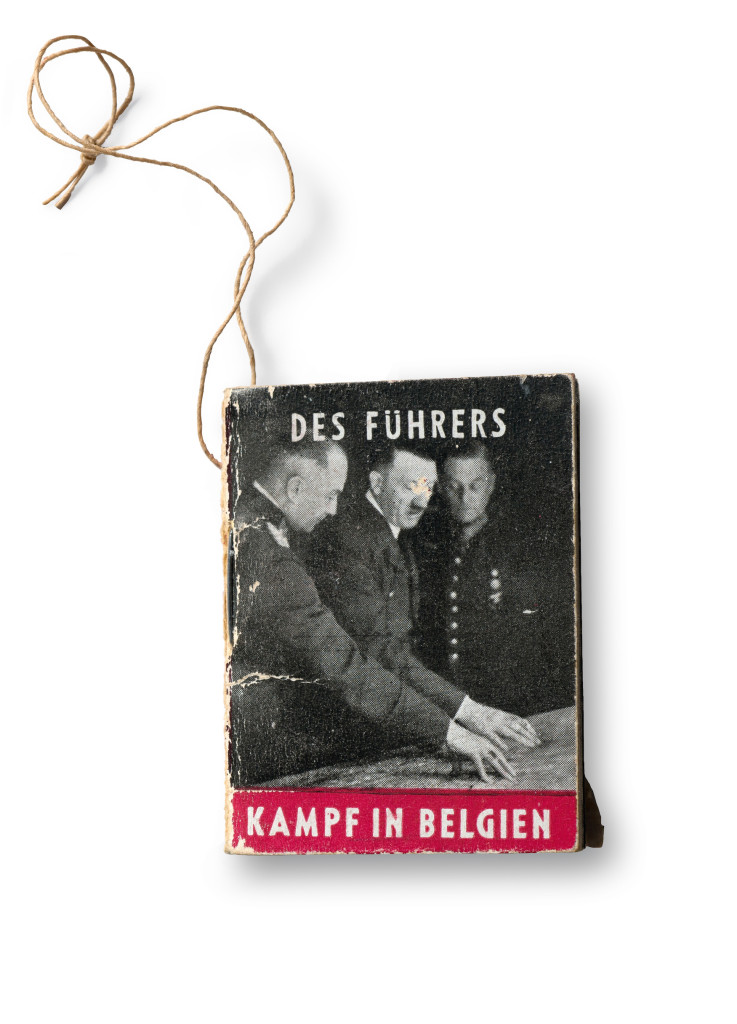

The chapter titled “Progress Report” is especially fascinating, chiefly featuring books of propaganda. There are photobooks from the Spanish Civil War, from both sides of the Palestine/Israel conflict, anonymous works from Angola, Libya, and Chile. New to me are the Winterhilfswerk-Heftchen, a series of tiny books, just slightly larger than an actual postage stamp, published in Germany between 1933 and 1945 by the Winter Relief Fund, a charity that gave contributors these books as small tokens of thanks. The text contains Nazi propaganda and the majority of the covers feature Adolf Hitler. They were published in sets of five or six, with a print run of 26 to 30 million. Even so, they seem to be thin on the ground, and not in fact very desirable to collectors, though perhaps that may change now that they’ve been given the Parr and Badger imprimatur.

Heinrich Hoffmann, ed., Winterhilfswerk-Heftchen (Winter Relief Fund Booklets), 1937–41

Anonymous, Album: Photographs of the Demonstrations Which Took Place in Palestine, 1933

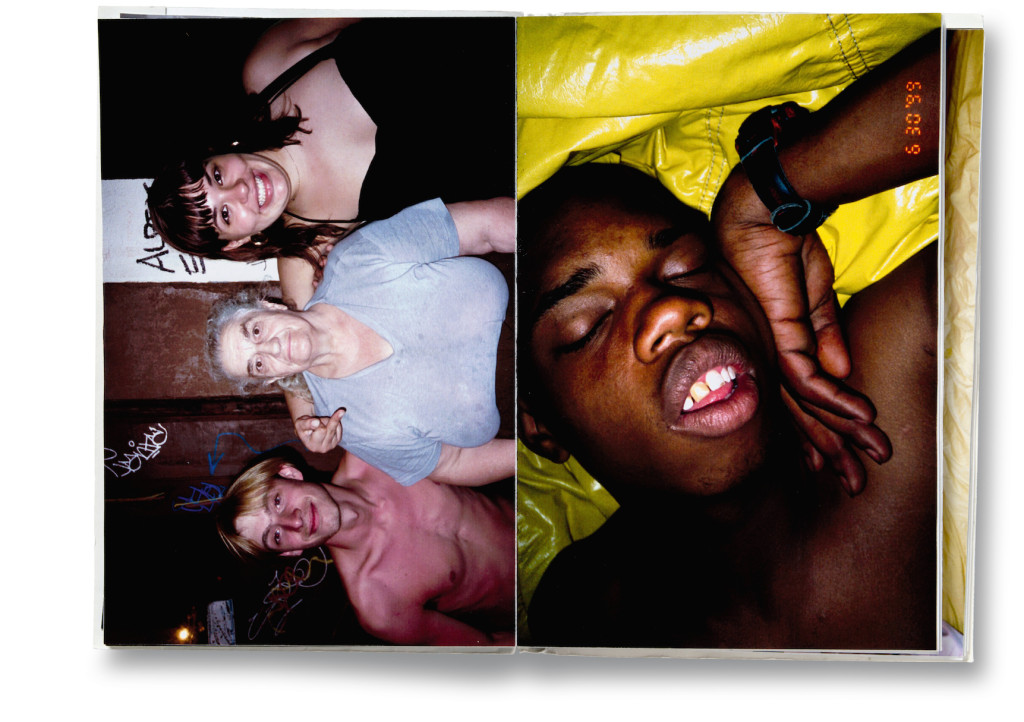

There’s a fair amount of sex and drugs in the new volume, (though the authors don’t seem to be great fans of rock 'n' roll, at least not its photography) especially in a chapter titled, with various layers of irony, “The Kids Are Alright.” That’s also the title of a book by Ryan McGinley (which originally came in an edition of 100 handmade copies — good luck acquiring that one), which is included here alongside work by fellow “bad boys” Dash Snow and Leigh Ledare. There’s Merry Alpern’s Hitchcockian Dirty Windows (1995), photographs taken surreptitiously, peering in through the rear window of a sex club near Wall Street, and Jessica Dimmock’s The Ninth Floor (2007), which documents life in a New York crack house. As Parr and Badger say of another book in the section, Self-publish, Be Naughty edited by Bruno Ceschel, there’s a conscious effort to blur the “boundaries between documentary and fantasy, between commerce and art.”

Ryan McGinley, The kids are alright, 2000

Ryan McGinley, The kids are alright, 2000

I’d say there’s also a blurring, or perhaps just a symbiosis between exhibition and voyeurism, though it’s a form of the latter that’s on display in a book titled Private Moments in Public Places, photographs by Stephanie Saia, text by Phyllis Prinz, published in 1979. It’s essentially images of the feet and legs of people while they’re using public toilets. I used to know this book very well when I was a bookseller in London in the 1980s. We stocked it, and it was the talk of the store. It satisfied a niche and (let’s face it) somewhat furtive market, and I admit I didn’t buy a copy at the time. It certainly seemed to make no great claims for itself as a work of photographic art.

And this, of course, is part of the Parr/Badger enterprise, not to hold some banal discussion about what is and isn’t art, but rather to reevaluate what is and isn’t worthy of attention, whether it’s art or not. The authors have benefited from a growing appreciation of (and demand for) photobooks, something for which they themselves are to a considerable extent responsible. Good for them, I say. Also, as magazine work has dried up for many freelance photographers, and as digital technology has turned us all into photographers, the publishing (often self-publishing) of quirky, limited-edition books has become a way for photographers to give their work status, and make it stand out from the virtual mush.

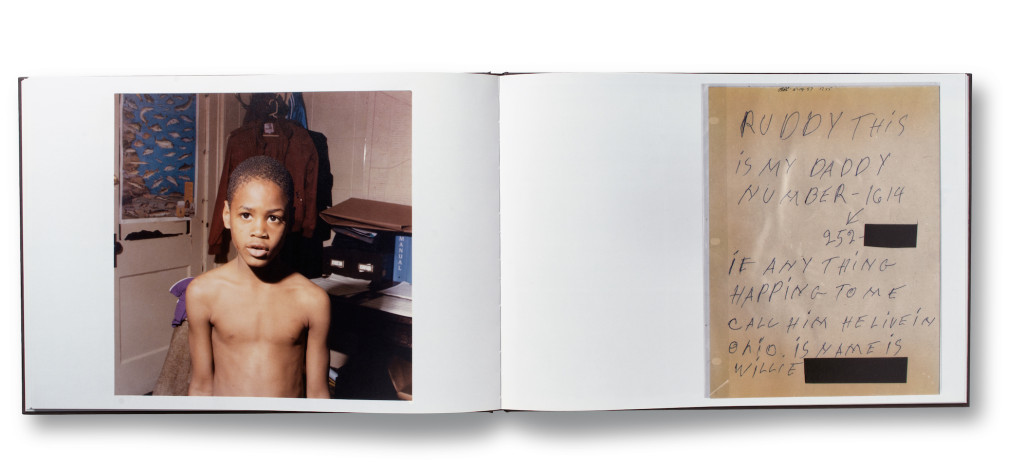

Parr and Badger make us aware of some of the amazing stuff that’s currently out there, and some of it’s even affordable, such as Found Photos in Detroit (2012) by Arianna Arcara and Luca Santese, a book of vernacular photographs and a few texts that the pair discovered while exploring the ruined streets of Detroit. The photographs are in poor shape, as are the people in them, and many of the images are from an abandoned police archive. The book came in an edition of 1,000, from Cesura, a (and I know these terms are far from straightforward) “real” publisher.

Arianna Arcara and Luca Santese, Found Photos in Detroit, 2012

Arianna Arcara and Luca Santese, Found Photos in Detroit, 2012

Far less conventional is a series of 96 books attributed to Joachim Schmid titled Other People’s Photographs. Each book contains 32 thematically related images harvested from online photo-sharing sites. Titles include: Cash, Cheques, Cleavage, Feet, Maps, Hotel Rooms, Objects in Mirror, Sex, Shadows. These books are print on demand and come via the online publisher Blurb, which not only makes everybody a photographer, but also can make every photographer the author of a photobook.

There’s clearly some serious intervention on Schmid’s part. He’s the one who selected, organized, and to a limited extent designed the book (using Blurb templates), although I suspect that not everybody who finds their work appearing in these books will be placated by the website’s disclaimer: “Copyright notice: All of the photographs used in this work as documentary material are merely integrating parts of a larger artwork. They do not constitute reprints or duplications in breach of the fee provisions of copyright law.” I think we might have a discussion about that, don’t you Joachim?

Some volumes in the Schmid series focus on food, and books featuring food photography have popped up throughout the Parr and Badger histories, including The Book of Bread, a 1903 baker’s manual described as looking like the work of a 1980s conceptual artist, as well as Nobuyoshi Araki’s Banquet (1993), a heartbreaking photo journal of the meals the photographer ate with his wife while she was dying of cancer.

The current volume contains a wonderful oddity titled The Catalogue of Meat Products, Conserves and Lard (1973), photographs by Jiøí Putta made for a Czech government department. It shows a series of deadpan yet somehow surrealist arrangements of sausages and meat products. It’s great, but I wonder what we’d have made of this book prior to the Parr and Badger history. Many would surely have dismissed it out of hand. And this is perhaps the authors’ greatest achievement. Photographic high art could always take care of itself. It was the eccentric and the ephemeral that most needed to be preserved, cherished, and celebrated.

For my own part, last month I bought a volume called Inside Chocolate: The Chocolate Lover’s Guide to Boxed Chocolates, by Hal and Ellen Greenberg, 1985, bound in gold foil. It’s a book for people who, unlike Forrest Gump, want to know what they’re going to get in their box of chocolates. So it’s a series of still lifes of open boxes of chocolates, with a guide to what each individual chocolate contains. It’s kind of magnificent, kind of comical, kind of stupid, and I’m sure I’d never have appreciated it, much less bought it, if it hadn’t been for the curiosities I’d seen in the Parr and Badger books. Rare and valuable it most definitely is not, but I have a suspicion that this may be one of the very few photobooks I own that Martin Parr doesn’t.

Images are taken from The Photobook: A History Volume III, by Martin Parr and Gerry Badger, Phaidon Press, $100.

¤

Geoff Nicholson’s books include the novels Bleeding London and The Hollywood Dodo, and the nonfiction The Lost Art of Walking. He blogs about “food, sex, obsession, and the madness of the mouth” at psycho-gourmet.blogspot.com.

LARB Contributor

Geoff Nicholson is a contributing editor to the Los Angeles Review of Books. His books include the novels Bleeding London and The Hollywood Dodo. His latest, The Miranda, is published in October.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Wish I Weren’t Here

The pleasures of postcards

Photography’s Chattering Ghosts

Why do we trust, or distrust, photographs? What are the forces that exist behind these images and why do they command such authority?

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!