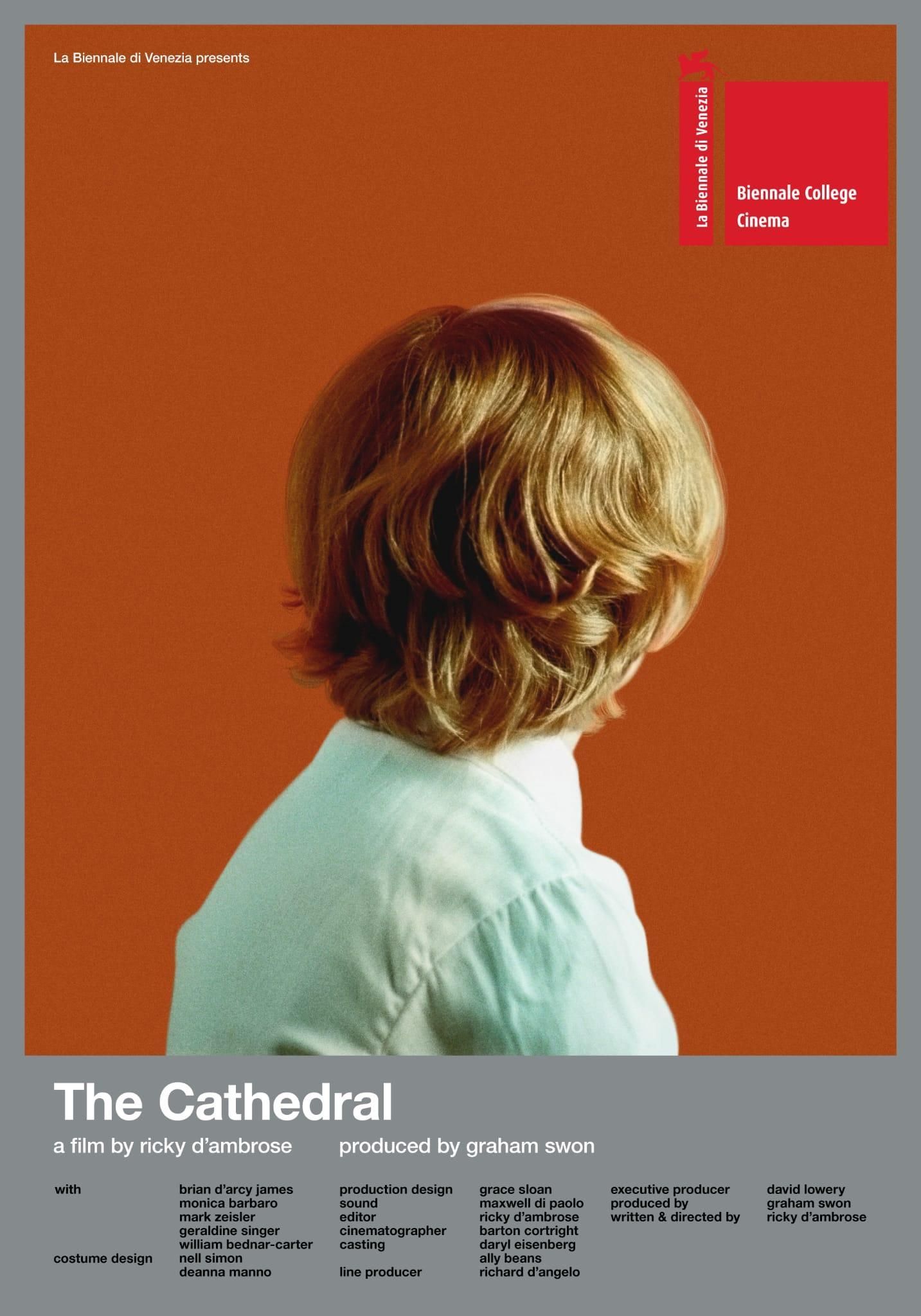

Clean Slate: On Ricky D’Ambrose’s “The Cathedral”

Max Levin writes about Ricky D’Ambrose’s autobiographical feature film, “The Cathedral.”

THE CATHEDRAL opens with a photograph — short sleeves and birthday cake, yellow tablecloth, late afternoon sun splashing on skin. An older man in the foreground turns to meet the gaze of the camera, but the shutter clicks early, freezing him in a torqued state of unfocused anticipation.

Filmmaker Ricky D’Ambrose savors these moments before or after connection, placing the camera just outside the scope of the action and poring over intimacy from a distance. He tells me that this photo was taken on Long Island in 1988 or 1989, and that it shows his parents, aunt, cousins, grandmother, and grandfather. The image is warmer than much of the film to follow, but consistent in its elliptical gaze.

The first time I watched The Cathedral, I left the theater frustrated by what I read as an overly calculated representation exercise missing a beating heart. Screening D’Ambrose’s earlier films seemed to confirm this impression, revealing the filmmaker's intention of separating style from content and prioritizing the former. In these films, elegant stylistic choices keep attention on a highly-polished surface, so that any depth below characters or stories is not in focus, serving as banal and anonymous background. Upon rewatching The Cathedral, what I initially wrote off in a few words evolved into deeper considerations about why some narrative filmmakers approach cinema with a skepticism of content and identity. I came to see what works in the film, what lingers, and what fails to stick. After the first viewing, I hadn’t even remembered this opening photograph. I had remembered the film beginning in a hospital.

The family photo cuts to a hospital bed after just three seconds: a close-up of an upturned hand spilling out lifelessly and alone. Mechanical sounds clang and clipped narration begins: “Jesse Damrosch was born in 1987, two years after the death of his father’s brother, Joseph.” The voiceover explains that Joseph Damrosch died at 38 from AIDS-related complications, and that his father would not allow him to come home when he was ill, ultimately refusing to acknowledge the illness that would kill him. The elder Damrosch insisted that his son died from a sudden liver disease caused by using “unclean silverware.”

This is all we ever see of Joseph Damrosch. The Cathedral endures in the wake of his absence, propagating a cinematic world marked by disconnection and discontinuity, attending to moments of unfulfilled contact. It skips ahead and backwards, mimicking an eagerness to capture impressions quickly, as with the hasty family photograph. In one early sequence, we glimpse a festive room, empty of people but full of unwrapped birthday presents for a child. Bells toll, and then a cut brings us to the exterior of a church, where wedding guests exit in procession past newlyweds.

With Jesse’s toys spliced before his birth and the marriage of his parents, The Cathedral subtly disturbs chronology to create scenes of quiet disorder. Later, a static shot of the remnants of Jesse’s cake for his third birthday appears almost 10 minutes before the scene when Jesse’s father moves to cut that cake, and he moves to cut the cake before the candles are even lit. Jesse sits silently as his mother chastises his father, who backs off so the perfunctory rituals can proceed. A flow of beautiful shots woven with dislocated sound, The Cathedral is a purposely awkward pageant of domestic life in which D’Ambrose seems to want to lose himself, and us, in the crowd.

Though it is never mentioned in promotional material, The Cathedral is an autobiographical film. Jesse Damrosch is a nominally altered version of the filmmaker, and the house where Jesse grows up and opens presents is D’Ambrose’s childhood home. The man at the center of the family photo is the same man who kicked his dying son out of his house. If the first image quietly links The Cathedral to autobiography and the family archive, it also previews how the film wrestles with absence, obfuscation, and the turbid space around silence. D’Ambrose would have been one or two years old at the time of the family photo, but he is nowhere to be seen.

In casting actors to perform scenes from the family history, The Cathedral excuses itself from the responsibilities of nonfiction storytelling, generating a sort of hollow realism reminiscent of Todd Solondz or Wes Anderson. The film is formally tremendous, but runs out of steam when it comes to producing sincere, embodied representations of sociality. Why does D’Ambrose handle his subject matter so coldly, especially considering how close to home it is? Even in the most heated moments, the digitally shot film retains a cool temperature with low saturation that looks ungraded. Instead of leaning into moments of intensity and confrontation, D’Ambrose’s roving cinematic gaze flinches away or operates with ambivalence.

Close-ups of hands, tables being set, and the exchange of money recall the gestural, aestheticized approach of Robert Bresson, but, in D’Ambrose’s films, these operate as intellectual exercises and formal homage. D’Ambrose is equally indebted to Chantal Akerman, whom he interviewed and filmed in 2013. Akerman spoke with compassionate clarity on the role of improvisation in her work — “Nothing is ever intellectual with me […] I’m much more intuitive and it’s through the process that I find out what to do” — and D’Ambrose’s filmic record of the exchange is exquisite. Yet, D’Ambrose’s precisely scripted films are far from this.

He often bases his films on his own life, self-marginalizing the protagonist to the point of invisibility and disappearance. Many of his films hinge on this displacement and an inability to realize himself (or his characters) as active and complex participants in their chosen communities. D’Ambrose opts out of depicting warmth or generative value in interpersonal connections, eschewing self-compassion and self-criticism alike. What could be thought of as an emotionally spartan film, The Cathedral can also be read as resentful and entitled in the way that D’Ambrose pulls back from his own particulars and instead leaves us with a generalized sense of alienation — from himself, from others, and from speech.

¤

Four actors play Jesse Damrosch in The Cathedral as he ages from infancy to young adulthood, but we rarely hear any of them speak. Jesse’s first words arrive just over 20 minutes into the film. In an elementary school assembly, he gazes off at a red bell before a reprimanding clap by his teacher returns him to attention. Jesse finally speaks to tell his classmate Pamela that her nose is bleeding. She stares back wordlessly, blood dripping toward her mouth. Lines that demarcate sickness or difference always flow away from or outside the central character, as if he is a neutral island untouched by the currents that surround him.

In “The Aesthetics of Silence” (1967), Susan Sontag identified the mythos of the artist’s need for self-estrangement, or “a craving for the cloud of unknowing beyond knowledge and for the silence beyond speech.” One can imagine D’Ambrose’s film in this spirit, trading dialogue for wordless extrospection. Sontag cites Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966) to demonstrate varied attributions of silence that can range from “the wish for ethical purity” to a “position of strength from which to manipulate and confound.” This grave complexity is also present in The Cathedral, which from the beginning links to the virus known for the equation silence = death.

Silence, death, and the scrubbing of identity in search of ethical purity are of key importance to D’Ambrose’s first feature, Notes on an Appearance (2018). In the film, David Hidell is a 28-year-old from Westchester, New York, who moves to Brooklyn and finds work assisting with research for the rehabilitative biography of a fictional philosopher, Stephen Taubes. Doctored New York Times headlines and Verso book covers contextualize Taubes as once lauded by the Left but viewed as an infamous reactionary, anti-Semite, and even alleged murderer at the time of his death. David is motivated to help on the large-scale project that unites archival research, philosophy, cancel culture, and reputation laundering. Halfway through the film, however, David disappears, and Notes becomes not so much a mystery about what happened to him as a sendup of social circles in Brooklyn.

It is eventually revealed that David’s decomposing body has been found near the beach in Jacob Riis Park, perhaps killed by strangulation. Employing David as a booster for a right-wing militant before inexplicably locating David’s corpse within a well-known zone for queer pleasure and activism, D’Ambrose’s film intermingles reactionary and leftist politics. The New Yorker’s Richard Brody includes Notes on an Appearance in a list of recent American films Brody calls “resistance cinema” — films that respond “to the rise of the far right and related tenets and syndromes.” D’Ambrose’s work thematically addresses right-wing politics, but it does not depict or encourage any kind of resistance. In a discussion with me, D’Ambrose suggested that Notes anticipated the politically fraught zone of Dimes Square, an infamous block in Downtown Manhattan where factions of the Far Left and Far Right infuse over lattes and negronis, interested in cynicism more than resistance.

It’s not very cool to talk about politics. Whenever I’ve gone to Dimes Square, I’ve heard people talking about Instagram. In his 2016 essay in The Nation, D’Ambrose lamented the Instagramification of visual culture, with preset filters and endless scroll allowing for an instantly achievable and digestible “look” without any hard-wrought (and, in his telling, more meaningful) “style.” In contrast to his glowing reviews of both of D’Ambrose’s feature films, Brody called this writing “a reactionary screed dressed in progressive rhetoric,” pointing out how D’Ambrose “picks, anoints, & exalts an aspect of classic art, claims the moderns haven't got it, & drubs them with it.”

The Cathedral is D’Ambrose’s feature-length elaboration on his essay’s bitter credo, with a nostalgic, classically rigorous style meant to serve as a reprieve from the flashy self-indulgence and noisy advertisements of social-media platforms. And yet, the film is self-centered, even as it looks outward and includes television ads for Kodak film and a commemorative coin for the 1986 centennial of the Statue of Liberty. The latter ad proclaims how “liberty is an idea, handed down from generation to generation, people to people,” and encourages purchasing the coin to “keep liberty in mint condition, forever.”

D’Ambrose’s work aspires toward mint-condition aesthetics, unmuddied by the complicating forces of sexuality, dreams, or even social life. The Cathedral avoids any reference to these elements of Jesse’s life, and in D’Ambrose’s preference for framing his film as a dynastic “rise and fall” of a family without the psychosexual layers of its protagonist, I am reminded of Lacan’s comment that the “starting point” of capitalism is “getting rid of sex.” While identity politics and depictions of queerness are profitable in art, D’Ambrose takes a different approach from current and earlier generations of queer filmmakers. In conversation with me, he praised Safe (1995) by Todd Haynes for its formal invention and daring, noting that the film “queers the form” without depicting many queer people. D’Ambrose prefers this to more recent “literal-minded and theatrical” films and “TV pilots in which you have upwardly mobile, conveniently diverse, Jonathan Demme–esque celebrations of humanity.” This prejudice emerges from D’Ambrose’s “fear that anything [he does] in which identity becomes foregrounded puts [him] in a ghetto.”

D’Ambrose cites Akerman in his defense of making films that cannot be ghettoized into the arena of queer cinema. The Belgian filmmaker told D’Ambrose that the need to place labels on filmmakers and films was an American impulse tied to the tradition of consumerism. Queer filmmakers are not obligated to make “queer films” anyhow, just as Jewish people are not obligated to make “Jewish films,” and so on. But it is one thing to make great films that are compelling enough on myriad fronts to transcend any one identitarian prescription. It is another thing to be a filmmaker who works away from the pack and crafts picturesque scenes only to obscure reactionary undercurrents. D’Ambrose tells me that his arrival to New York in 2007 with “grand ambitions about insinuating [himself] with a certain group of people” led to his being “sidelined,” and that David in Notes is a proxy for D’Ambrose. The shivers of isolation and injury extend through most of D’Ambrose’s work. While he is successful at avoiding the idealized, adolescent haze and sexual awakening of Richard Linklater’s Boyhood (2014), the prevailing mode of neutered complaint from the perspective of a silent, innocent son ends up feeling derivative of Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life (2011).

And I can’t help thinking that for Akerman, the daughter of Holocaust survivors, the term “ghettoize” surely meant something different than it does for D’Ambrose. Indeed, Akerman’s work is considered important to the development of what would become known as New Queer Cinema, even though Akerman did not allow her films to be shown in women’s film festivals or lesbian film programs. Notably, Akerman did screen her films in Jewish film festivals.

Centering characters who are sensitive and bookish but not gay, D’Ambrose rejects any association as a queer filmmaker. When asked by a friend years ago why he did not have gay characters in his films, D’Ambrose replied that he did not necessarily have straight characters in his films either. Making films from the perspective of an undifferentiated outcast by not announcing (or even by renouncing) sexuality, D’Ambrose aims for a carefully cropped middle ground through which he can sail to art-house stardom.

But there is no spirit or breath in these sails, and the ship must be evaluated on its own terms. Identities of artists are under more scrutiny than ever, but so should be the art itself. The long-standing tendency for white male artists to make work as if their subject positions are blank or neutral can perpetuate supremacy. Here, it is not power as much as sadness, regret, and pity that radiates for and from the family. D’Ambrose was inspired to make The Cathedral after a long-simmering feud flared up with one family member harshly delivering the silent treatment to her sister while at the funeral of their mother. In the film, this scene reveals generations of pain folding over itself, and The Cathedral is an uneven attempt to unravel and understand — perhaps in vain — how we got here.

¤

In the June 21, 1993, issue of The New Yorker, the short-story writer and novelist Harold Brodkey published “To My Readers.” The writing begins bluntly: “I have AIDS. I am surprised that I do.” Brodkey located his “adventures in homosexuality” in the distant past, taking a position of prideful resignation about his mysterious illness. Ailing but not too disappointed about what he will be missing after death, he writes that he is grateful for having accomplished much in his life and glad that he is not a young person cut down in or before the prime of their life. He thanks his wife for her unwavering support and embraces death as “a silence and a privacy and an untouchability,” adding that “[d]eath is preferable to daily retreat.” Later on, Brodkey admits that “underneath the sentimentality and obstinacy of [his] attitudes” is “a quite severe rage and a vast […] extensive terror, anchored in contempt.”

After the novelist and critic Samuel R. Delany read Brodkey’s text, he set out on writing what would become his 20th book of fiction, The Mad Man (1994), which opens with the lines: “I do not have AIDS. I am surprised that I don’t.” The story draws on HIV-negative Delany’s own decades of homosexual adventures in New York City’s parks and other public spaces. The novel follows a graduate student, John Marr, whose research about a problematic and brilliant philosopher, Timothy Hasler, leads him into a messy and revelatory “pornotopic fantasy.” Inverting and rejecting the shame and moral superiority in Brodkey’s text, Delany envisages queer possibilities for pleasure and partnership even in the face of a deadly virus and the “discursive disarticulation that muffles and muddles all.” Delany was so incensed by the murderous discourse around AIDS and the lack of scientific research about the disease that he included a 1987 peer-reviewed medical journal article investigating behavioral risk factors for HIV infection — at the time of Delany’s writing, the most recent one — as an appendix to The Mad Man. There, at the end of the book, fact joined fiction not with admonitions against what to put in your mouth but an imaginative foray into what you can put into it and what can come out of it. Silence is not the problem but, instead, what happens around it. In 1983, Delany wrote that the work of the artist is to make noise in “an attempt to shape a silence in which something can go on.”

The Cathedral is a parade of marriages, birthdays, graduations, and funerals, with moments of lying in beds and looking out windows and under doors. Television footage from natural disasters, war, and terrorism is intercut, such that an aerial view of a man walking in Katrina floodwaters marks the advance of time. The most compelling stretch in the film occurs when Jesse receives a video camera for his 13th birthday. Voiceover recounts Jesse’s response to the gift:

He recorded indiscriminately, although rarely as a way to memorialize the things around him. The many hours of moving images […] reflected less an interest in memory than in measure. For the great distance that had opened up between Jesse and the world, on the eve of his adolescence, could now effectively be scaled, by videotape and light.

There is still a gulf between D’Ambrose and the world, which his films address by focusing on characters who stand handsomely and silently alone. Solitude reigns, and what, if any, is the obligation that a solitary individual has to their family or to other collective bodies? Conceiving of disconnection as a generative void to be measured with curiosity and warmth gestures toward what The Cathedral might have been. Instead, the narrative is preoccupied with the minutiae of the filmmaker’s family tree, becoming a highly stylized memory exercise that abdicates responsibility of meaningfully shaping silences.

And what about the name? Cathedrals are soaring architectures of power, enclosure, and sonic manipulation. Recently, in some right-wing circles organized around Curtis Yarvin, “the Cathedral” has become a favored term for “mainstream academia, journalism, and education” organized into a “set of institutions that produce and propagate” synoptic progressive values for which there is manufactured consent. To those who believe in the Cathedral and the Synopsis, this progressivism — justice, equality — is eroding social order, and they favor a hard reset for our society gone haywire.

D’Ambrose was unaware of this alt-right association when he titled his film, and The Cathedral is less militant yet similarly concerned with coercion and the ideal of a clean slate. At one point in the film, Jesse flips through a book about the building of the Chartres Cathedral, reading about flying buttresses and other architectural achievements as well as the people who died in the construction of the church and were buried inside of it. Jesse survived, and yet D’Ambrose still seems trapped in structures built by those around him. In The Cathedral, there is no way out except for light and sound, which shine through the hearty gap under bedroom doors.

¤

LARB Contributor

Max Levin is a writer and artist with interests in sound, performance, documentary, science fiction, and the essay form. He has written for X-TRA, Screen Slate, and the art galleries 56 Henry in New York City and Lauren Powell Projects in Los Angeles. His sound work has been presented at Andrew Edlin Gallery and performed elsewhere in New York City. He lives in Brooklyn.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Nightmares Worth Indulging: On Feminist Press’s “It Came from the Closet”

Grace Byron reviews “It Came from the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror” from Feminist Press and editor Joe Vallese.

Masculinity Is the New Prey: On Ander Monson’s “Predator”

Adam Fleming Petty reviews Ander Monson’s memoir-in-criticism, “Predator.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!