Catalonia in Peril: On Manuel de Pedrolo’s “Typescript of the Second Origin”

Manuel de Pedrolo's "Typescript of the Second Origin" is a novel both born from and about politics: in particular, the politics of identity.

By Dale KnickerbockerSeptember 15, 2018

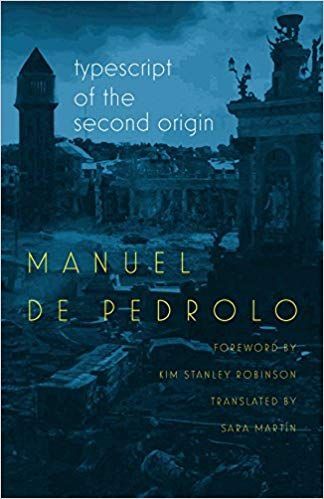

Typescript of the Second Origin by Manuel de Pedrolo. Wesleyan. 184 pages.

WHY SHOULD THE English-speaking world of 2018 be interested in Typescript of the Second Origin, a novel published originally in 1974 in Catalan, a language spoken by just over five million people in Northeastern Spain, written by an author little known outside of that community?

The fact that Hugo, Nebula, and World Fantasy Award winner Kim Stanley Robinson agreed to write the foreword testifies to the novel’s quality, as does the fact that it has been translated into 11 other languages. It is the best-selling novel of all time written in Catalan — a language and culture that, while small, boast their own rich literary heritage and whose capital, Barcelona, boasts one of the healthiest publishing industries in the world. The novel has enjoyed a recent resurgence in popularity and, for the first time, seems to be attracting serious consideration by scholars: a beautiful tri-lingual (Catalan, Spanish, and English) edition was issued to celebrate Barcelona’s hosting of the 2017 Worldcon, and was also timed to coincide with a special issue of the journal Alambique: Revista Académica de Ciencia Ficción y Fantasía (4.2, May 2017).

One could also note that the novel is a classic, a point of reference in Catalan culture. Since shortly after the 1975 death of dictator Francisco Franco, Typescript of the Second Origin (henceforth Typescript) has formed part of the standard curriculum in the region’s secondary schools. Moreover, the work’s “foreignness” does not make it inaccessible; it does not leave readers with the impression that they are “missing something.” Its story of two children who struggle to survive the aftermath of the destruction of civilization makes for a profoundly moving, human story with universal appeal. And Typescript treats many of the time-honored themes of science fiction. The post-apocalyptic narrative is both a utopian and dystopian fiction, one that reflects upon questions of gender, race, and power. As Robinson notes in his foreword, it also participates in the small genre known as the Robinsonade, and critics have posited the influence of such Anglophone classics as William Golding’s Lord of the Flies and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. This first English translation notably comes at a moment when Catalan nationalists’ efforts to separate from Spain have launched it onto center stage in European news outlets, and it may paradoxically be Typescript’s “otherness,” the quality that makes it very much a Catalan novel, that makes it most relevant to contemporary readers in Europe and the United States.

First things first: According to Sara Martín’s introduction, Manuel de Pedrolo (1918–1990) was born in a small village in Eastern Catalonia, the son of an impoverished aristocratic landowner and conservative Catalan independentista or nationalist (not to be confused with the Spanish nationalism of the dictatorship). The author himself was a fervent lifelong nationalist and a socialist, which made him one of the most frequently censored authors under the Franco regime (1939–1975). That regime forbade the teaching or publication of materials in Catalan as well as its use in public discourse such as newspapers, and also brutally repressed any form of expression that suggested Catalonia was a separate ethnic or cultural — much less political — entity. Pedrolo was as prolific as he was eclectic: his 128 works include novels, short stories, poetry, drama, and essays, as well as translations of works in English. They participated in literary genres and movements from the existentialist novel and the experimentalist nouveau roman to science fiction and detective fiction. His publications never quite coincided with what the academy considered important literature at the time — a fact that, combined with his refusal to be pigeonholed (or to participate in the required social aspect of literary self-promotion) caused scholars in Catalonia to virtually ignore his work until after his death. Pedrolo was equally out of step with his times politically: he was a hard-line supporter of complete independence for Catalonia during Spain’s transition to democracy, when the region’s leaders were negotiating what amount of independence and authority the autonomous community would have. His politics would fit right in with the procés, or program for independence, of the coalition of nationalist parties currently in power.

The novel is presented as the diary of an adolescent girl, Alba (symbolically, “Dawn” in English), and her younger neighbor, Dídac. The two survive an attack by extraterrestrial flying saucers whose sonic weapons destroy buildings and cause the death of all mammals, though other life continues unharmed. The children survive because Alba was saving the boy, who is black, from drowning after being bullied by racist children, and the water prevents the sound waves from reaching them. For some unknown reason, the aliens do not invade, although the children do encounter one (who has both porcine and primate characteristics) that they must kill. The pair finds themselves the sole survivors in their village near Barcelona. Surviving at first by foraging in the remains of their village, Alba decides they should set out to preserve human knowledge by saving books from libraries. They learn to raise their own crops, she teaches herself to care for their health from medical books, and the boy demonstrates a remarkable aptitude for mechanics, salvaging generators and repairing first automobiles then a tug boat. The two youths set sail in it one summer, hugging the Mediterranean coast and visiting parts of Greece, Italy, and France. The few human survivors they encounter are either insane, or so savage (attempting to kill Dídac so they can rape Alba) that the girl must kill them to save herself and the boy. When Dídac matures, love grows between the two, and they eventually have a son. Although the young man dies when a building caves in on him, Alba plans to mate with their son to continue the species — no doubt a shocking ending at the time.

In Typescript’s dystopian setting, Alba’s leadership and wisdom — particularly in saving all human knowledge possible — constitutes the novel’s feminist message. Their child’s biracial genetics implicitly condemns racial or ethnic oppression. As is frequently the case in apocalyptic literature, the work employs the paradigm of destruction and rebirth both to reflect upon the ills of its own contemporary reality — racism, sexism, moral and political repression — and to suggest a path toward a new and better reality. The biblical influence is not limited to this narrative pattern, but also implied by the novel’s structure: the paragraphs of its five “Notebooks,” supposedly typescript versions of Alba’s handwritten notebooks, are numbered. Ironically and significantly, religion is entirely absent in the novel. This absence not only puts forth the author’s idea of what a utopia would look like, but also creates a silence that eloquently condemns the omnipresence of religion in the public sphere and discourse in Franco’s ultra-Catholic right-wing regime. The incest in Typescript’s ending seems to equate religion and guilt with a repression, in all senses of the word, that the children have shed. Pedrolo’s notion of utopia would thus seem to be post-patriarchal, post-racial, and perhaps post-moral. Therefore, though politics are not explicitly mentioned in any way (despite the Francoist repression alluded to on several occasions), Typescript is a novel both born from and about politics: in particular, the politics of identity. The only common criticism centers on how the children seem too intelligent for their age, and seem to learn complex skills too quickly, especially for autodidacts. The symbolic need for innocence, for a sort of moral tabula rasa, and for characters with whom any reader could sympathize, seems to have outweighed verisimilitude in the author’s decision.

Robinson’s foreword and the translator Sara Martín’s introduction both serve as paradigmatic examples of what such texts should be. The former offers a brief, plain-language explanation of how science fiction works, intended for the uninitiated reader, and outlines the novel’s main themes, explaining the allegorical relationship between the aliens’ attempted destruction of humanity and the Franco regime’s attempted destruction of Catalan language and cultural identity. The latter offers fine contextualization, thoroughly yet succinctly covering the author’s life, his times, and his status in Catalan letters. It discusses the novel’s place in his opus, its marketing and publication history, and, above all, provides an excellent summary of the political situation that made the work possible for those not versed in the complexities of the relationship between the region and the rest of Spain.

A word needs to be said about the translation itself. Martín overcomes the challenge of transforming the lengthy sentences, with the multiple subordinate clauses characteristic of romance languages, into the more paratactic structures of English, and the result is a prose that sounds natural in the mouths of the young characters. She avoids the flaw endemic to most translations: an overdependence on the use of cognates, common even in situations where they are inappropriate to the character’s idiolect, or so arcane as to be unknown by most readers. If readers did not know Typescript was a translation, it may never occur to them.

Let’s return now to the work’s continuing relevance. The Spanish constitution approved in 1978 makes no allowance for secession from the nation by any of its constituent autonomic regions, and one of Spain’s powerful governing parties, the conservative Popular Party, refuses to consider any changes in that regard. For a number of years, a coalition of nationalist parties from left through right has governed in Catalonia and, given the Spanish government’s intransigence regarding Catalan self-determination, this coalition held a referendum on independence on October 1, 2017. It was not recognized as legitimate by Spain’s government and was ruled illegal by its Constitutional Tribunal. The boycotting of the plebiscite by all the major national parties and their regional affiliates allowed for an overwhelming victory by the independentistas, although every one of the many surveys done by groups of all political stripes invariably show Catalonians to be evenly divided between nationalists and those who wish to remain part of Spain. Due to reports of hundreds of citizens wounded by police, foreign news media offered a very sympathetic view of the nationalists’ cause. The reports were later shown to be greatly exaggerated, the result of a Twitter campaign urging people to flock to hospitals to say they’d been attacked by police. This sympathetic reaction was aggravated by conservative president Mariano Rajoy’s heavy-handed imprisonment of political leaders responsible for the plebiscite and invocation of Article 155 of the Spanish constitution, placing Catalonia under the direct control of the central government.

As I was originally writing this review earlier this year, I watched journalists react to the investiture of nationalist Quim Torra as the new president of the Generalitat, the Catalan government; he took the place of Carles Puigdemont, who was either in exile or on the lam (depending upon your perspective) in Berlin, where the crime of sedition with which he is charged is not recognized. Torra immediately pledged to continue the procés of transferring all government functions to the regional authorities. Catalonians today are not oppressed and enjoy the same rights as every other Spanish citizen, but many claim the right to self-determination. All of this seems quite innocent, even reasonable, until one notes the xenophobia of many of the independentista leaders’ comments, such as President Torra’s referring to Spaniards as “animals in human form who spew out hate” and “carrion-eating beasts, vipers, hyenas with defective DNA” (translation mine). Many independentista actions have also raised concerns about the status of non-Catalan speakers in a future Republic of Catalonia (the languages are currently co-official and bias against anyone based on language illegal): one decree in the Balearic Islands, for example, stipulates that physicians must attend all patients only in Catalan, whether the patient speaks it or not — a measure that makes their leaders look more like Boris Johnson or Marine Le Pen than Simón Bolívar or Thomas Jefferson.

On June 1, an unprecedented motion of censure brought down President Mariano Rajoy’s conservative government in Spain. With the support of Catalan pro-independence parties, an interim coalition government was installed with the secretary-general of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party Pedro Sánchez as prime minister. This new government has been much more conciliatory toward Catalonia, splitting the hard-line independentistas and those parties more willing to compromise. Even so, in the larger global context of Brexit, the elections of Donald Trump in the United States and Mateusz Morawiecki in Poland, and the formation of a far-right coalition to govern in Italy, we can see that Typescript of the Second Origin says something vital about the relevance of cultural difference in a world where we are witnessing the rise of xenophobic right-wing parties. Will a future Catalonia be independent or not? And if so, will it more closely resemble Pedrolo’s utopia or the Spanish regime that repressed its own cultural diversity?

¤

LARB Contributor

Dale Knickerbocker is Linda E. McMahon Distinguished Professor of Foreign Languages and Literatures at East Carolina University, where he teaches Hispanic languages, literatures, and cultures. He is an associate editor of the Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts and Alambique, and a member of the editorial advisory boards of Extrapolation, Brumal (Spain), and Abusões (Brazil). He is editor of the critical collection Lingua Cosmica: Science Fiction from Beyond the Anglophone Universe, and author of Juan José Millás: The Obsessive-Compulsive Aesthetic and the upcoming Spain Is Different? Historical Memory, Modernity, and the “Two Spains” in Turn-of- the-Millennium Spanish Apocalyptic Novels.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Russian Cosmism Versus Interstellar Bosses: Reclaiming Full-Throttle Luxury Space Communism

Aaron Winslow reviews the collection "Russian Cosmism," edited by Boris Groys.

Two Almodóvars

What happened to Pedro Almodóvar? Bécquer Seguín looks at "Julieta" to find out.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!