Carceral Aesthetics

“Marking Time” is a compelling survey of the creative work of incarcerated artists.

By Daniel FernandezApril 28, 2020

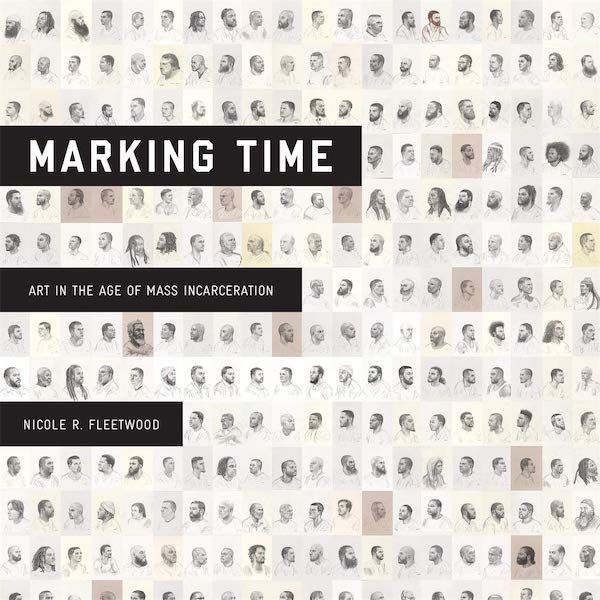

Marking Time by Nicole R. Fleetwood. Harvard University Press. 352 pages.

AMERICA’S FIRST PRISON REFORMER, Benjamin Rush, loathed the festivities that accompanied public punishment. These events, he argued, did little but make “bad men worse” because “a man who has lost his character at a whipping-post has nothing valuable left to lose.” Rush sought a more enlightened approach: the creation of penitentiaries in remote locales, nestled among mountain peaks or deep within boggy swamps. His fellow citizens did not share such a vision. Instead, they built the republic’s first house of punishment on Philadelphia’s Walnut Street, hoping that its public presence — and the promise of “unremitted solitude” inside its stone walls — would frighten the aspiring criminal while avoiding the public abuses that were routine under British rule.

As Walnut Street filled with prisoners, another monument to higher thinking emerged in Philadelphia: The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Together, these two institutions — the prison and the museum — spoke to the promise and peril of the new nation. As Alexis de Tocqueville later observed, America seemed to offer “the most extended liberty” for its citizens while promising the “spectacle of the most complete despotism” for anyone who erred.

This spectacle remains an immutable feature of American punishment. Prison memoirs have been a public fascination for almost two centuries, while uprisings and the routine mistreatment of incarcerated people continue to furnish material for radio programming and television. Films like San Quentin (1937) and 20,000 Years in Sing Sing (1932) shot scenes on location; Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song (1979) was only possible because Gary Gilmore auctioned off the rights to his “life story.” More recently, Netflix’s Orange Is the New Black generated seven seasons of award-winning television, and last May the streaming service ventured into near-dystopian territory when it debuted Jailbirds, a reality TV show about women incarcerated in a California jail.

These popular narratives have promised to make life behind bars visible and yet they often seem more interested in lurid violence than the concerns of incarcerated people. Put bluntly, mass culture has been remarkably successful in commodifying the horrors and humiliation of incarceration, but it has done little to create a movement that might challenge the laws, political actors, and institutions that permit these routine abuses to happen.

Nicole Fleetwood’s new book, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, is a corrective to this trend. Offering an explicit political message (“a future without human caging”), it directs attention away from outsiders’ depictions of incarceration toward the creative work of incarcerated artists and their allies. Over seven loosely related chapters, Fleetwood documents these artists’ practices — what she broadly refers to as “carceral aesthetics” — along with their efforts to critique and reimagine the United States’s systems of surveillance and punishment. She relies as much on her own experiences as a member of a family touched by incarceration as those of the artists in her book, and she brings together an impressive array of paintings, sculptures, murals, and photos that speak to the impact of incarceration on American life.

The artists she describes face considerable difficulty in both conceptualizing and executing their projects. Their prison cells limit, quite literally, the space available to them. They also only have access to limited supplies in commissaries and hobby shops, and they face prohibitions on certain materials (many facilities outlaw red and blue paints, for example, because they contain metals or other flammable elements). Some work with nothing but paper and pencil; those on Louisiana’s death row cannot make anything without the approval of a warden, as if all the powers of creation have been stripped away from them.

Incarcerated artists rely on a variety of techniques to overcome these barriers. Some create DIY objects like screwdrivers and tattoo guns in a process called “mushfake,” which Fleetwood likens to bricolage. Others, such as exonerated Ohio prisoner Dean Gillispie, “procure” state-controlled goods from a motley array of sources: discarded cigarette boxes, dental clay, copper wire, and textile scraps. Gillispie’s preferred creations are miniatures of midcentury Americana, such as movie theaters, trailers, and diners, which he made as a way to manage his two decades of wrongful imprisonment. He tells Fleetwood that gathering materials was often a months-long endeavor, requiring complex bartering with both guards and incarcerated people.

Gillispie might seem nostalgic for an earlier time, whether in his own life or in the mythic American past, but most artists strike more overtly political poses, exposing how the state robs and dispossesses marginalized communities through hyper-incarceration and over-policing. A few artists also consider the time they have taken from others, using their art as a means of healing and reconciliation in spaces where the state provides few opportunities for genuine transformation. Among the most striking pieces Fleetwood discusses are those created by artists living in the bare conditions of solitary confinement. Moliere Dimanche Jr. wrote his 2016 visual memoir It Takes a Criminal to Know One almost entirely on the back pages of legal proceedings, in a grotesque style filled with violent political imagery. Another artist, Ojore Lutalo, developed collages from newspapers and magazines to communicate the harrowing conditions inside New Jersey’s Management Control Units. For Lutalo, as for many others, art making conveys an identity — and presents an opportunity for self-representation — that penal authorities rarely, if ever, allow.

These barriers to expression hardly disappear after incarceration ends. One artist, Jesse Krimes, reports feeling rudderless after his release. Without the limitations imposed by prison life — including the constant need to improvise in his creative practices — he seems almost overwhelmed, especially when the day-to-day challenges posed by reintegration are added to the mix. “[Y]ou’re removed from society for such a long period of time,” he says, “that when you come home everything’s changed. […] It always feels like you have to catch up.” For others, incarceration looms large in a more material way: Jared Owens, a formerly incarcerated artist, goes so far as to use jars of soil from his former prison yard in his projects.

There are more conceptual challenges, too, especially because the label “prison art” leaves so little to the imagination. One expects motifs of stone and steel, barbed wire and metal chains, colorless goop served on plastic trays. As Baz Dreisinger notes in her 2016 book Incarceration Nation, “Art can be an obstacle because of the very thing it does so well: dazzle us, and then distract us, with beauty.” More than dazzle, art can overwhelm. In one of the book’s most intimate sections, Fleetwood describes the bulky packages she received from her cousin during the first few years of his incarceration. “I dreaded opening an envelope from him if I could feel that the contents included something akin to the thickness and flexibility of photo paper,” she writes. “I could not look.” It became easier with time, Fleetwood explains, but one has the sense that anxieties still linger. In one family photo with her incarcerated cousin, she yearns to alter his expression, “to paint his face over with a cold stare, a mischievous grin, something other than that look of resignation, of being caught up in a narrative that is bigger than the self.”

The problem Fleetwood and many of the artists in her book grapple with is how to convey this larger-than-life narrative. The digital artist Josh Begley poses the question explicitly when he asks, “What does the geography of incarceration in the United States look like?” His answer is 4,916 aerial images of facilities from across the country, a latticework of green and brown and orange hues, tiny buildings dwarfed by vast expanses of water, crops, and desert. Parsing Begley’s work, one is left with the unmistakable impression that the geography of incarceration is the geography of America, that the two are inseparable from one another. And yet, with their unearthly perspective, his satellite images render these sites almost anodyne.

A better answer comes from Sable Elyse Smith, the final artist to appear in Fleetwood’s book. Commenting on a recent exhibition, Smith remarks that “my life is like all these little fragments […] these unfinished stories, or bits that just have to be truncated.” But rather than try to unify, gloss, or paint over, Smith explodes: fragmentation becomes the core of her creative process, not some limitation. Fleetwood, like Smith, is at her best when she deals in the partial and personal, rather than fleeing to the vistas provided by art theory. But even if her treatment is occasionally meandering, Fleetwood finds a balance between abstraction and anecdote. And, in amplifying the stories of those marked by incarceration, she makes visible the individuals and families the carceral state has tried so hard to disappear and silence. “I was lost,” one man explains. “Art broke all my chains.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Daniel Fernandez is a writer and researcher based in New Jersey. His writing has appeared in Smithsonian, In These Times, and The Nation.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Carceral Progressivism: On Savannah Shange’s “Progressive Dystopia”

A new book shows why social justice “wins” are often really defeats for Black Americans.

The Carceral Invasion: On Brett Story’s “Prison Land”

A prison is less a maze of walls than “a set of relationships,” argues filmmaker Brett Story in a follow-up book to an acclaimed film.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!