Freedom by Jonathan Franzen. Picador. 608 pages.

The Twenty-Seventh City

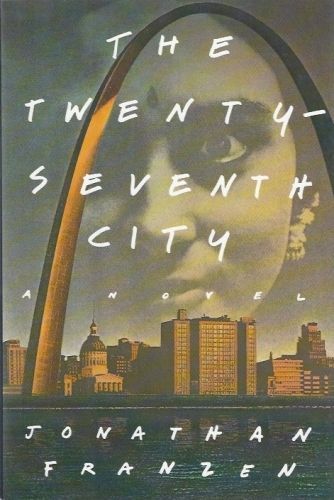

THIS MONTH MARKS 25 YEARS since Jonathan Franzen made his debut as a novelist. From all accounts it was an impressive debut — the critics called The Twenty-Seventh City masterly, riveting, even visionary; The New Yorker reviewed it properly, not in its Briefly Noted section; and Franzen received a fan letter from David Foster Wallace for pulling off such a “freaking first novel” — but the larger population failed to notice that this owlish New Yorker with Missourian roots had the makings of a Great American Novelist. The tinkle of popular fame was completely absent.

This was probably because the novel was not an easy read. Steeped in its own brilliance, it was that strange oxymoron, a bureaucratic thriller. Set in 1984, it tells the unlikely story of a police chief from Bombay who is hired to be the police chief of that most resolute of Midwestern cities, St. Louis, Missouri. Her name is S. Jammu — the initial S is meant to evoke the dark absurdity of Josef K. — and she proceeds through charm, espionage, terror, sex, kidnapping, and murder to blackmail, corrupt, and subjugate the influential citizens of St. Louis. She has a group of Indian confreres to help her, including a fake princess named Asha, and a former lover, Singh, an exceptionally well-sketched bisexual Sikh Marxist provocateur. Jammu’s ostensible goal as police chief is to revitalize the inner city by stamping out crime and driving investment toward it. This done, she will engineer a merger between the mainly black city of St. Louis and the affluent white county of St. Louis, and make a multimillion-dollar real-estate killing in the process. Her main opponent is the “Christ-like” and incorruptible businessman Martin Probst whom she calls “a self-righteous asshole.” Masterminding and bankrolling the Bad Brown vs. Upright White coup from faraway Bombay is Jammu’s stylish and ruthless Kashmiri Brahmin mother who happens to be a cousin of Indira Gandhi. The coup starts smoothly. In seven short months, Jammu, on the strength of her charm and ability, becomes a socialite and socialist, a ghetto goddess and Lion Club darling. Even the almighty New Yorker is beguiled into printing poems that go, “For Gary Cater, Frank Perdue,/ Bono Vox and S. Jammu!” Then, of course, stuff happens, and everything starts to go to hell.

Like many first novels out to impress, this one too was an overreach — and practically cross-eyed from all the clever postmodern winks dropped across in its 500 pages. Think of a Curry Midwestern flavored with Kafkaesque conspiracy, Pynchonian paranoia, and suburban noir in the DeLillo tradition. Add to this neurotic weave a sprinkling of nods made to St. Louis native T. S. Eliot’s "The Waste Land" (Jammu’s mother is called Shanti) and George Orwell (Jammu’s shadowy Big Sister surveillance unfolds in the year 1984). With its bewildering cast of Indian and American characters, spidery subplots, and toiling plotline of a city-county merger — “municipal science-fiction” is how The New Yorker elegantly described it — The Twenty-Seventh City came across as too clever by half. To use a proximate architectural analogy, it had the scale but not the beguiling simplicity of St. Louis’s Gateway Arch.

Two decades later, in 2010, Franzen, by then a world-famous writer promoted on Time magazine’s cover as a Great American Novelist, admitted as much in an interview to the Paris Review, disarmingly calling himself “a skinny, scared kid trying to write a big novel.” If that description sounds similar to Barack Obama calling himself “a skinny kid with a funny name who believes that America has a place for him,” there is certainly a parallel in the cheeky — and quintessentially American — audacity and hope that emblazoned the start-up ambition of both these men.

Franzen had to wait until his third book about another crumbling Midwestern family, The Corrections, to be “bathed in the bright publicity of the American air” — to use a tart phrase from one of his favorite novels, Edith Wharton’s The Custom of the Country. His second novel, Strong Motion, where earthquakes are used as a metaphor for the tremors that tear apart a couple, also got decent reviews but failed to sizzle. But after the symphonic success of The Corrections in 2001, every word Franzen has since written or spoken has made the headlines and been vigorously debated. He is now widely, and quite rightly, considered to be a preeminent novelist of his generation, celebrated for his exploration of the repressed sexual longings and dark material heart of the American family. In 2010, he published his fourth novel, Freedom. Once again it was set in the Franzenian comfort zone of the Midwest, and once again about a family that splits like sour milk, but eventually reunites (remorse over split milk, apparently, is worth it). The critics couldn’t find enough words to praise it, but among the laurels were a few dissenting nettles, and they were thistle-sharp. Freedom, said some critics, was a “schematic” and “sloppily written” literary soap op that ended on a happily-ever-after sentimental note.

I was among the nettled. Perhaps more disappointed than nettled for reasons that are, like all really credible reasons, entirely personal. It had to do with the depiction of Lalitha, the gorgeous, brainy, charming, honest, too-good-to-be-true Indian-American character in Freedom. I couldn’t help compare the hollow and tokenistic way she was treated to the masterfully complex portrayal of Franzen’s first Indian-American character, Jammu. Judging the two novels on the basis of the portrayal of two Indian characters may sound narrow, but in fact it offers a clear optic through which to track Franzen’s arc from a raw, skinny-kid novelist, desperate to strike out and write against the grain, to a formidably accomplished but ominously mainstream writer, who has too much at stake to go for broke.

A range of striking similarities between The Twenty-Seventh City and Freedom bolsters the Jammu-Lalitha comparison. At the heart of both novels is a crazy scheme. Jammu, a mixed-up Marxist revolutionary, creates an imaginary group of terrorists called the Osage Warriors to reduce the citizens of St. Louis to a gibbering mess — what she calls “the State” — so that she can manipulate them. In Freedom, the “greener than Greenpeace” Walter Berglund, in a naive attempt to save an endangered bird and fund a campaign on population control, climbs into bed with a Texas millionaire and agrees to a Faustian trade-off that involves mountaintop removal, one of the most destructive and widely condemned mining practices in the world. On a more specific familial level, too, the parallels are notable. In both novels, seemingly solid Midwestern families, the Probsts and the Berglunds, are torn apart. The first rip in both cases is caused by a teenage child storming out of the house — Luisa, Martin and Barbara Probst’s spoiled blonde daughter, decamps to live with her damp photographer boyfriend; and Joey, the precocious, selfish son of Walter and Patty Berglund storms out to shack up with the Republican neighbor’s besotted daughter. The loss of their beloved offspring blows open the deeply buried unhappiness in their doting-housewife mothers — explored by Franzen with extraordinary Friedanesque sensitivity in both cases — leaving both mothers vulnerable to sexual predators. Barbara is ravished and kidnapped by the sinister Singh, while Patty, in a queasy moral dodge typical of Freedom, sleepwalks into sex with Walter’s rock-star best friend. Knocked flat by the adulteries of their wives, the two staunchly loyal husbands, red-cheeked Walter Berglund and pink-cheeked Martin Probst, are rendered ripe for seduction by the brown-skinned sirens of the subcontinent, Jammu and Lalitha. One would not be overstating things to point out that Freedom is in many key ways The Twenty-Seventh City repurposed.

What makes the presence of Jammu and Lalitha in his oeuvre remarkable is that Indian-Americans — and for that matter Chinese, Arabic, African, and Latino immigrants — with meaningful roles are still a woeful rarity in the fiction of the major white American novelists, lending credence to the Nobel Prize committee’s longstanding charge of insularity leveled at American fiction (a charge that Franzen rejects). The fact is that while the USA might correctly vaunt its melting-pot credentials, its literary fiction is as creamy as a suburb with a good school district. A couple of rare Indian-American characters that come to mind are Anhil, the deliberately caricatured donut man in A. M. Homes’s This Book Will Save Your Life, and Ann Patchett’s half-Indian protagonist in State of Wonder, the pharmacologist Marina Singh. Otherwise, it is mostly left to Jhumpa Lahiri or Yiyun Li to write about their communities, and to wait for their novels to then be ghetto-garlanded as “immigrant fiction.”

It comes as a pleasant surprise, therefore, to see that Indian-Americans bookend Franzen’s fiction, making them something of a rara avis. His first novel opens with S. Jammu with “blood-starved, bluish” lips and knee-length socks hunched like a bony schoolgirl over her police desk, and his last novel ends with a bird sanctuary named after Lalitha, “a pretty young dark-skinned girl.” The contrast between the two descriptions, the brooding child-like menace of the first and the ersatz lyricism of the second, are uncommonly revealing, but more on that later. Franzen’s interest in India goes back to his days as a schoolboy, when he wrote a comic play on the police in colonial India (the character of Jammu originated here). There is something intriguing about his interest in South Asia. After all, Franzen’s background is almost parodically White Christian Male American. He acknowledges this in The Discomfort Zone, describing his upbringing in suburban St. Louis as taking place in “the middle of the country in the middle of the golden age of the American middle-class.” He has never visited India — his research for The Twenty-Seventh City was based on reading, among others, the India books of The New Yorker writer Ved Mehta — nor do his numerous autobiographical essays hint at any Indian presence or influence in his life. What, then, drew his unremitting gaze all the way to the tropical subcontinent with its bewildering politics and history?

It’s hard to tell — an email to the writer got a polite but un-illuminating response. Perhaps the most plausible explanation is offered by Stephen J. Burn, author of Jonathan Franzen at the End of Postmodernism. ““I’d always assumed that the Indian link in Twenty-Seventh was a joke about language’s imprecision — the same word ambiguously denoting Native Americans (who make a great deal of sense in St. Louis) and the Indian subcontinent, which has a less obvious link,” said Burn in an email interview. “Since Pynchon is to some extent the novel’s hidden master, we can think of Franzen’s Indians as a parallel to the way Pynchon overloads the word Tristero with different referents in The Crying of Lot 49, and so drains it of any single meaning.” Indeed, The Twenty-Seventh City plays extensively and laboriously with this duality. Jammu is “the Indian chief” — or “Injun bitch” — out to “scalp” St. Louis and so on. Whatever the reasons, the accuracy and authority with which a young Franzen writes on India in his first novel, the capacious cultural and political detail, and the surprisingly accurate insights into the humor, ethics, idiom, and psychology of his Indian characters, is nothing short of virtuoso. With a few muscular swipes he touches on the caste system, the class system, and the endemic philosophy of expedience that dominates daily life in India. To cite a delightful example, one of Jammu’s henchmen complains dolefully that the Christ-like Martin Probst “is having no sins but morality.” Franzen is spot on here, he has his finger on the patois and the mojo. Which is why his “item-girl” — to use a Bollywood term — treatment of Lalitha comes as such a terrible letdown.

Like Jammu, Lalitha is a diminutive iron fist in a velvet glove. Her ferocious charm can bulldoze hard-bitten Texas millionaires into acquiescence. The problem is that she has the plasticity and depth of a Bollywood cardboard cutout. She is introduced interestingly enough — Walter’s lascivious rock-star friend thinks of her as a “hot little crackpot,” as crazy about saving birds and the Planet Earth from the cancer of overpopulation as Walter is. Her beauty and virtues are endlessly extolled: her glowing olive skin, her expert skills as a driver, the clink of silver bracelets on her slender brown arms, how she is at once rounded and slender, her clipped lilt, how sexily and percussively she pronounces her o's. As far as genealogy goes, we are told she is Bengali and born in Calcutta. This crumb is tossed our way for two reasons: it allows Walter to rhapsodize that his young Missouri-bred assistant “born in the warmth of southern Asia, was the sunny person who brought a momentary kind of summer to his soul.” And it allows her to express her disgust (italics not mine) at the “density and suffering and squalor” of the city. “Her disgust had pushed her, on her return to the States, into vegetarianism and environmental studies, with a focus, in college, on women’s issues in developing nations.” Lalitha is in a six-year relationship with an “arrogant but driven” Indian boyfriend who is studying to be a heart surgeon in Nashville, and she has engineer parents in Missouri who want her to marry and be a good wife. The perfect package then: the model hardworking, college-educated Asian immigrant with the sexual appeal of a harem. A “stereo-tropical character,” to borrow a knockout term from the mouth of Homes’s Indian donut man.

Franzen then tries, lazily, to tweak the stereotype. Unlike most good Indian girls, we are told that Lalitha, who lives on soy lattes, can’t even cook an egg. She coldly rebuffs an offer by Walter’s daughter to cook a Bengali meal even though the daughter has, like a good liberal, carefully researched the foreign cuisine. A great entry point into Lalitha’s past one thinks — how did this vegetarian girl grow up in a carnivorous, fish-eating house? But no, Franzen can’t be bothered to describe Bengali food. This is a fundamental lapse for a novelist who uses food as one of his most visceral sociological probes. Who can forget the sensuousness with which he depicts the awfulness of Caucasian vegetables — think of little Chip in The Corrections staring at his plate of mashed rutabaga that has “the texture and temperature of wet dog crap on a cool morning”? Or the deft way he conveys the strong and (to some noses) repugnant odors of certain ethnic foods, whether it is street gyros, “a heavy stinking bag of lowest-grade meats and pita” or the sour reek of pickles of a Korean college roommate? Disappointingly, then, we learn nothing about the food and customs that Lalitha grew up on.

Finally, Franzen decides to detonate the stereotype. Lalitha blithely announces to an embarrassed Walter that she is going to have her tubes tied. This is where things fall apart. If this spunky young woman is so radical in her reproductive choices, why would she be in a six-year relationship with a conservative boyfriend who almost certainly wants children? She tells Walter she is “a freak,” but even gullible Walter wants to learn about the emotional and ideological springs that drive his young lover. “Do you know why? Why you’re different?” he asks. It’s the question on every reader’s lips. “No, but I know what I am. I’m the girl that doesn’t want a baby,” is all we get from Lalitha. Where did this bourgeoisie Bengali girl get her activist fire? What is Lalitha all about? Why is she in the novel? What’s her surname? What’s her backstory? And that indeed is the crux of the matter: there is none.

Franzen’s greatest strength as a novelist is his ability to create compelling backstory. He excels at telling the reader where his characters come from in order to illuminate and soften their cruelties and kinks, their sexual and moral pathologies. Sometimes, he errs on the side of excess. Walter Berglund’s story is traced all the way back to when his abusive, poverty-stricken father emigrated from Sweden to America (the name Berglund could be a nod to the Swedish Bergson family in Willa Cather’s O Pioneers!). Too discursive a backgrounding perhaps, but it helps us understand that Walter Berglund’s Pierre Bezukhov-like blandness hides a black rage at the world — the rage of the self-made man. (Martin Probst, who dropped out of college, simmers with a similar rage; when pressed, he calls his upper-class wife a “cunt.”) We are told about Patty’s super-liberal parents, her wealthy grandfather, his tightness with wine, his old-man perversions. For crying out loud, even Joey’s college roommate gets more airtime than Lalitha. She hatches into the novel, fully formed, like a hot little crackpot from an exotic eggshell and crashes out — literally — in what must be the most blushful plot device, when her car is hit by a coal truck and flies off an embankment in West Virginia. It’s almost as if she cares so deeply about overpopulation that she whacks herself out of the picture — parodic, but that’s the impression one is left with. Her death allows for an eventual reconciliation between Walter and Patty. The Berglunds are reunited and Lalitha gets a ceramic tile with her name on it outside a bird reserve. As the London Review of Books so mockingly titled its review of Freedom: "So long, Lalitha."

Logically, since Lalitha is good and Jammu bad, we should like the former and dislike the latter. This doesn’t happen. Jammu is evil but endlessly fascinating in the energy she exudes. When this young woman from Bombay is chosen as the police chief of St. Louis, the city is “appalled,” but she takes charge “before anyone could stop her.” The reader, too, is appalled by her thuggish schemes, but she gets a lock on our sympathy before anyone can stop her. Martin Probst is bowled over when he finally sees his bête noire, in a trench coat, small, assured, and attractive, and the reader feels the draw of her amoral animal magnetism. Probst asks Jammu the same question Walter asks Lalitha: Who are you? Deftly, she doesn’t answer, but Franzen does. He takes the reader back to Kashmir to show us how Jammu, a vulnerable half-Indian, half-American student of electrical science joins Singh’s group of revolutionaries. Her mother wants to marry her off to a 43-year-old landowner “because she was a bastard and the landowner had asked.” The mother, a minor character but with an iron influence on her daughter, vibrates with vitality — an upper-class Kashmiri Brahmin who elopes with an American journalist, dumps him, returns to India with baby Jammu, mixes herself a drink every evening, has a Muslim cook, eats beef at home, reads Asimov, and loathes Singh. Jammu, named for the Hindu part of the strife-torn Jammu and Kashmir Valley, remains an enigma, but an entirely convincing one. We never really understand what makes her into this conscience-stricken monster drunk on speed and power. Franzen hints at the persistence of an internal conflict between the idealistic, thumb-chewing child Susan (that’s what the mysterious S stands for) and the feral woman Jammu, and eventually the child wins. Haggard and sour and beaten by an apathetic referendum that votes against the city-county merger, Susan Jammu stands alone in the police washroom. In a brilliantly executed Jamesian scene reminiscent of Isabel Archer staring into the dying fire as she reflects on her disastrous marriage, Jammu reflects on her misdeeds and the death of Barbara Probst, as she methodically soaps her hands with the “pink ooze” from the spigot. It’s as if she’s washing her hands with gore — a repulsively paradoxical image. Cleansed, she shoots herself.

With his bizarre plot involving what he referred to in his Paris Review interview as “a bunch of Indians” — The New Yorker reviewer, somewhat more insultingly, called them “dark subversive hordes” — Franzen went out on a limb. The Indians in his novel, to the woman, are portrayed as immoral and ruthless. A shallow reading could easily point the finger of racial prejudice against Franzen, but only if one is stupid enough to conflate the pervasive prejudice of the characters with the voice of the author. In one passage Jammu is described through the eyes of Martin Probst, as “unconcealably Third World” looking “like she needed a bath.” This could come across as offensive, but it is saved from that vulgarity by the fact that it reflects, and damns, the provincial American gaze of anything un-White and non-Western. And also because Jammu’s diabolism has cheapened her into a haggard and unclean heap. In contrast, Franzen’s repetitive harping on Lalitha’s dark skin — including in the closing line — is jarring and makes one query his fixation with it. That, along with his persistent pigeonholing of her as Bengali. Yes, she is Bengali, but she is also as American as Walter’s Swedish daughter. That is never taken into account.

Which is why the sexual-colonial metaphor that Franzen uses for the seductions of Martin and Walter works in the first case but not the other. Singh quips that Jammu’s conquest of Probst symbolizes the black city-white county merger, and indeed Jammu’s entrapment of Martin Probst is just that, a ruse to get him to support the merger, to which he is implacably opposed. Fresh from her conquest, she is in a phone booth giving Singh orders to kill Martin’s wife even as “Martin’s semen was falling into her underwear.” The metaphor also feeds into Franzen’s “Indian” duality theme. Jammu, a Marxist, and therefore a “Red Indian,” has avenged history by subjugating a white man whose wife she will now dispatch. Later, when Asha, the fake princess, breaks a sacrosanct rule and flies her plane — what else but a Cherokee — through the Gateway Arch, and “the Arch spreads its legs” to permit her to pass through, the sexual phrasing is unmistakable. In Freedom, Lalitha follows her boss, Walter, around on her knees offering to give him sex. Walter is desperate to sleep with Lalitha, who is as young as his daughter — Lalitha, Lolita, get it? — but is afraid of being “another overconsuming white American male who felt entitled to more and more and more: saw the romantic imperialism of his falling for someone fresh and Asian, having exhausted domestic supplies.” Overconsumption may be Walter’s pet peeve, but the “romantic imperialism of his falling for someone fresh and Asian” is an utterly gratuitous thought, and comes off sounding like some fancy geopolitical erotica that Franzen has stirred in. Especially because a few pages later Walter rapidly gets over his colonial compunctions and ends up with his face and nose “impregnated with the smell of her vagina.”

What gives The Twenty-Seventh City its power is its sure-footed evocation of the political climates of two very different democracies, the world’s oldest and the world’s largest. The reader is immersed in the USA of the 1970s and 1980s, the “Era of the Parking Lot”; the era when white flight from the inner cities is complete; the era when the country is emerging from the horror of Vietnam and Nixon’s crookedness. The reader is also slam-dunked into an India emerging from the Indira Gandhi–declared 1975 Emergency, the darkest chapter in its democracy, so brilliantly satirized in Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children. (Incidentally, like Franzen, Rushdie too read Ved Mehta before writing his novel.) What is Jammu but a rapacious child of Indira’s Emergency, with its forced sterilizations, jailing, and bulldozers? She imports a version of these unconstitutional tactics with her to St. Louis, and is brazen enough in a post-Watergate environment to bug the homes, offices, and clubs of her enemies. Her streak of asymmetrical gray hair emphasizes her connection to the “Enlightened Despot,” and when she sinks low enough to order Singh to kill Barbara Probst, Singh thinks of her as “Indira.” Franzen also touches momentarily but searingly on the shameful phase that engulfed India after Indira Gandhi’s assassination, when hundreds of innocent Sikhs were hunted down and lynched as revenge for the two Sikh bodyguards who killed her. Significantly, Shanti, the name of Jammu’s mother, Indira Gandhi’s sinister cousin, means peace or nonviolence, a word that has as hallowed a place in India’s political scripture as “freedom” does in America’s. Both Indira and Shanti have subverted Mahatma Gandhi’s idea of nonviolence, and here is Franzen commenting on it all. The Twenty-Seventh City is as much an Indian novel as it is an American one.

Freedom is nakedly political too. Franzen’s derisive satire of Indira who has “a smile in which Jammu saw nothing but machinery” is matched by the radioactive hatred he pours on Bush and Cheney in Freedom. He distills this hatred into a grotesque cameo, a rich pro-Israel “philosopher” with a small skull and “white, white smile,” who tells Joey: "We have to learn to be comfortable with stretching some facts.” But while Jammu’s evil catches up with and destroys her, in Freedom, Franzen pulls his characters back from the abyss (except for poor Lalitha). Walter sees his Faustian compact for what it is, has a public meltdown, and becomes a YouTube hero. His redemption is less troubling than his son Joey’s. Joey, like Joe Keller in Arthur Miller’s All My Sons and Milo Minderbinder in Catch-22, sells defective goods to the US army. Keller’s defective aircraft engines cause the death of 21 pilots, and finally guilt drives him to suicide. But there is no bloody blowback in Freedom. A conscience-stricken Joey stops being evil, repents, and ends up rich and happy, growing shade-grown coffee instead. What happens to the rust-encrusted junk he sells to the army in Iraq for military trucks? How many lives and limbs are lost because of them? Are the parts ever used? We never know because Franzen never tells us. Joey comes out of his greedy venture unpunished, his “shell of coolness” intact, a toothless cautionary tale. Unless of course there is an even more cynical critique at work here. That in the world of Halliburton wars, there are no consequences, just happy endings all around. So long, consequences.

To return to Franzen’s India foray, the full force of how deeply he has digested his research came home to me not in the India-heavy Twenty-Seventh City, but in a throwaway detail at the climax of The Corrections. It occurs when Alfred Lambert, the upright, sexually repressed, turd-and-enema obsessed patriarch of the family is finally forced to acknowledge that he has been unraveled by dementia. He appears distraught and hysterical before his family dressed like this: “A lunatic dhoti of bunched and shredded diapers hung from his loins. ‘Look at this,’ he said…” The droll deployment of the word dhoti in conjunction with the word loins is a masterstroke because it ingeniously inverts the standard Western description of Gandhi’s loincloth or dhoti as diaper. Even more attractive is that Franzen doesn’t care to explain dhoti, just as in The Twenty-Seventh City he doesn’t explain Hindi words like lathi (brass-tipped bamboo stave used by the police as a baton) or pakora (a batter-fried snack), forcing the reader to look it up if he or she cares enough to do so. Looking it up helps. As Jammu says: “You know, the Kama Sutra enjoins you to linger.”

Franzen does not linger with Lalitha. It’s as if he wrote her in because he already had all this India research from his first novel and found her a convenient channel through which to recycle it, and, in the process, add pigment to the story. A pert bit of affirmative action. Nothing is more telling than this telltale slip: both S. Jammu and Lalitha have glossy black hair that smells of “coconutty shampoo.” Really? Two women from two different backgrounds, generations, and geographies just happen to both use “coconutty shampoo?” Why? Because they are Indian? Whatever happened to that skinny, scared kid out to write a big novel?

¤

Nina Martyris has written for several publications including The Times of India, The Guardian, The New Republic, Slate, Salon and The Millions.

LARB Contributor

Nina Martyris has written for several publications including The Times of India, The Guardian, The New Republic, Slate, Salon and The Millions.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Our Distraction: Franzen’s Kraus Project

Jonathan Franzen has done something of real consequence, making Karl Kraus known and available in a new way.

Essays on Jonathan Franzen’s Latest Book and His First

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!