Box, Office: Eve Gleichman and Laura Blackett’s Queer Comedy of Tech Life

Marcie Bianco appreciates “The Very Nice Box,” the new book from Eve Gleichman and Laura Blackett.

By Marcie BiancoSeptember 23, 2021

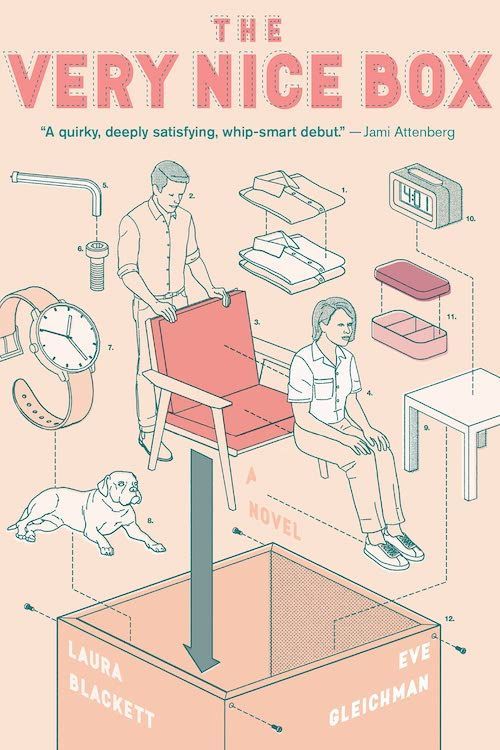

The Very Nice Box by Eve Gleichman and Laura Blackett. Mariner Books. 368 pages.

AVA SIMON, THE protagonist of Laura Blackett and Eve Gleichman’s The Very Nice Box, measures her life in boxes, boxes of time she refers to as “units.” But also literal boxes. As the senior product engineer at STÄDA — a modern furniture company evocative of that global Scandinavian company known for its compact, affordable furnishings as well as its meatballs — she specializes in designing boxes: the Sensible Bento Box, the Singular Shoe Box, the Memorable Archives Box. Her current, multiyear Passion Project, however, is a much larger box and also the book’s central conceit: the Very Nice Box. Using this box as both object and metaphor, The Very Nice Box provocatively and entertainingly explores how attempts to design our lives might directly conflict with actively living them.

Ava loves her work, the “meticulous engineering without frills or gimmicks, just the ideal intersection of geometry and utility, where each component existed for a reason.” And this functionality is the guiding ethic of her spartan, methodical life, where each day is conceived of

as a series of efficiently divided thirty-minute units. One unit for showering, dressing, and brushing her teeth. One unit for breakfast and coffee. One unit for walking [her dog] Brutus along the perimeter of Fort Greene Park. One unit driving to the STÄDA offices in Red Hook.

Her days, like her boxes, are “beautifully organized, uniform, and solitary,” save her one friendship with a longtime colleague who works on her team.

That Ava conceptualizes life in boxes may seem like a curio, and, in The Very Nice Box, the reader can certainly indulge in the authors’ dazzling latticework. Take, for instance, the fact that Ava’s deceased fiancée, Andie, was a STÄDA engineer who specialized in designing clocks — that is, machines that spatialize time, quantifying time to make it structured, measurable, and knowable. For their engagement, Andie presented Ava with a wristwatch instead of a ring — a watch that she crafted, called the Precise Wristwatch, with a face that measured 35 millimeters in diameter, representing the number of months they had lived together.

But boxes are more than just a personal obsession and a lifestyle, and what might initially seem conceptual or coy about The Very Nice Box’s attention to detail quickly becomes part of its substantive emotional heft. The day of Ava’s engagement, we learn, took a devastating turn that completely shattered her life. In light of this revelation, Ava’s carefully designed life reads as a response to the trauma of losing everyone she loves. Ava manages her life — she manages to get by — because of the safety, predictability, and reliability of compartmentalizing her life into boxes. There is no change, no disruption, just the comfort of monotony, habits that offer a prophylactic against her feelings of despair, guilt, and grief.

Trauma reminds us of the fragility of life, and the experience can make us want to hold tight to what we can control. And so the novel, through the box as a metaphor for this containment, presents both Ava and the reader with this question: what happens when what we do to get by stops us from actively living? Ava, plagued with survivor’s guilt, lived through a horrible experience, but it is immediately clear to the reader that her life lacks vitality — not only spontaneity, but also any emotional intensity. Primarily, she lacks what boxes themselves foreclose, or are structurally foreclosed to: relationships.

But life always finds a way of unlatching our boxes. This unlatching, of course, is a plot necessity — even Ottessa Moshfegh’s protagonist, who arguably does nothing in My Year of Rest and Relaxation, desires a year of sleep. Similar to this dark comedy, Blackett and Gleichman leave the austere philosophizing to others and engage with Big Questions about life with delicious wit and clever wordplay that strip bare our basest human impulses. Doing so, they show how these impulses are summarily marketed and commodified. In our world, like the novel’s world, growth and solutions now go hand-in-hand — businesses can brand themselves as social enterprises, and “designing your life” becomes both a university course and a wellness mantra.

In Ava’s case, this unlatching occurs with the introduction of a new head of product at STÄDA, Mat Putnam, who Ava quickly dismisses as a “douchebag bro.” If Ava’s life is symbolized by a box, then Mat’s life is represented by a disco ball — for him, a literal disco ball hanging from the rearview mirror of his red sportscar, which, he says, “symbolizes my own personal change and growth.” Mat’s character provides Blackett and Gleichman their most fun, as they gleefully use him to skewer douchebag bro rhetoric. As Mat rebrands STÄDA as a “solutions-based company,” he shouts, “Hey, amigo!” at Jaime while offering up a high-five, and says eyeroll-inducing phrases like, “I really need to fire my unhappiness so that I can hire my desire to work for me instead.” The authors taunt the reader with a character so hyperbolically stereotypical as to defy stereotype. Mat is even an active member of the Good Guys, which he calls a self-care program to help men “do good in the world” but which feels eerily like a men’s rights group caping as a professional fraternity. Blackett and Gleichman’s indictment of douchey tech-bro language runs parallel to their interest in boxes — language, too, places limits on what complexities can be felt or acknowledged.

And yet, just as the authors are about to cast their line into a sea of absurdity that would relinquish the novel to the realm of corporate culture satire, they pull back. Mat is no simple foil. Ava, to her own astonishment, finds Mat charming and soon develops what she regards as a “warmth” toward him, as if being with him nurtures her back to life. Here, the characters’ names are symbolic: in Hebrew, Mat/Matthew means “gift of god” while Ava, a derivative of Chava, means “life.” When Mat buys Ava a cheeseburger — something she has not indulged in for years — he tells her that she is “allowed to enjoy her life.” And, with this permission, she takes a bite and gives herself “this small pleasure.” Mat does indeed bring Ava back to life, or life back to Ava. His disco ball swings like a wrecking ball into Ava’s “relatively small life.”

With Mat, Ava emerges from her proverbial box. “Falling in love with Mat was the feeling of jumping from a very high perch, yet somehow it was also the feeling of safety.” By opening herself up to Mat, by inviting him into her life, the established intimacy also does some necessary emotional work for Ava. Blackett and Gleichman demonstrate this through flashback chapters that flow seamlessly from and into the present relationship with Mat, that show an incremental working through of her trauma as her relationship with Mat deepens. And Ava acknowledges this growth in her — how, before Mat, she had boxed herself in and refused all relationships for fear of additional loss that would obliterate her. With Mat, “she could let someone in” and no longer “avoid [her] own life.”

Entering into a relationship — sexual or otherwise — with another person opens up a different way of orienting ourselves toward the world. Attraction offers us pleasure and also can promise some kind of use value — a personal leveling up or growth, or what the theorist Lauren Berlant referred to as the inherent optimism of all attachments. They describe this optimism as “the force that moves you out of yourself and into the world in order to bring closer the satisfying something that you cannot generate on your own.” And this aspect of relationships invokes what the theorist Barbara Johnson called the ethical importance of using people. That is, each relationship presents us the opportunity, Johnson explains, “to trust, to play, and to experience the reality of both the other and the self.”

Some relationships encourage us out of our own box and into what Johnson calls a “space of play and risk.” Other relationships box us in. They entrap us. Knowing the difference can be harder than you think. And despite Mat’s positive demeanor as the “solutions guy,” there is something slippery about him. Here, the authors play frankly with the storytelling method of “showing not telling” — and we all know that when someone professes to be “a profoundly good person,” they are usually trying to persuade you to not look behind the curtain.

It is ominous that Mat gives Ava the nickname “Lamby,” and as the story progresses, the reader witnesses Mat’s attempts to lead Ava astray of the truth. Mat ostracizes Ava from her only friend, Jaime, whose repeated warnings that Mat is a “total scammer” are dismissed as jealous pecks at Ava’s newfound happiness. Alone in his orbit, Mat’s lies soon become “disagreements,” which quickly turn into simple “misunderstandings.” The Good Guy dissolves into Cruel Optimism personified: the relation, Berlant explains, where the possibility of happiness is forever unattainable because it is “actually an obstacle to your own flourishing.” And, like all relations of cruel optimism, Ava just cannot let go, because Mat has brought back “some semblance of normalcy to [her] life.”

On the subject of “normalcy,” a significant aspect of this relationship, for Ava, is that it is with a man. And yet, to their credit, Blackett and Gleichman refrain from dramatizing this difference by refusing to make sexual identity a box, or a categorical fixture, for Ava. To have done so would have rendered this an entirely different — and hackneyed — novel. Reading this treatment of sexual identity through my own lesbian spectacles, I find one of the authors’ most intentional overtures concerning the question of how to live life. Life should be formed outside categorical boxes that are both prescriptive and descriptive, and that do not reflect life’s dynamism. Rather than boxing in queerness, the authors suggest queerness as a lens for seeing, reading, and, arguably, for their own storytelling, which refuses trite or stereotypical generic moments.

There are certainly humorous moments, such as when Ava reflects on how constant the excitement of her relationship was with Andie in comparison to how she feels things with Mat are slowing down: “Was this what it was like to settle into a long-term relationship with a man?” But, more importantly, it is the lens of queerness that enables Jaime, a gay man, to see Mat’s facade as “some cis het bro” who is a “special combination of inept and entitled.” And, while the rose-colored glasses of love taint Ava’s vision, it is eventually her own queer lens that saves her by allowing her to identify elements of Mat’s actions and behavior as dangerous forms of control — in common parlance, the “toxic masculinity” of a “fragile, manipulative man.”

The suspenseful unraveling of Mat and Ava’s relationship hinges, quite humorously, on Ava’s Very Nice Box. The irony of life threaded through the book — that the feeling of being alive often conflicts with ability to stay alive — deepens as the box reveals its Pandora-like nature. The box is not an either/or metaphor for life but a both/and. Boxes protect us but they also limit us. They keep us alive while restricting our aliveness. The lesson Ava learns from her relationship is in fact the ethical use value that Johnson spoke about. Ava realizes that, regardless of the design, living one’s life is found in connections that “expand [her] world.”

While the conclusion suffers slightly from too much exposition — reminiscent of a tidy Scooby-Doo ending — the reader is left in awe of the realization that the authors successfully pulled off playing Mat Putnam themselves. The story charms, it entices, and it keeps the reader in their hands, wanting more.

¤

LARB Contributor

Marcie Bianco is a writer and editor based in California. Her writing projects include a feminist manifesto on freedom and a novel about lesbian academic affairs.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Not Your Grandfather’s Hollywood Novel

“Chinatown” meets “Barton Fink” in this brilliant dark fantasy about Hollywood — and the deserts that surround it.

Semi-Plausible Histories: On Torrey Peters’s “Detransition, Baby”

A sparkling debut novel challenges ideologically charged notions of gender and motherhood.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!