Black Love Adrift in a Sea of Whiteness: On Asali Solomon’s “The Days of Afrekete”

A new entry in the genre of the Philadelphia Novel, characterized by a tangle of law enforcement, interracial romance, and social alienation.

By Miranda FeatherstoneMay 19, 2022

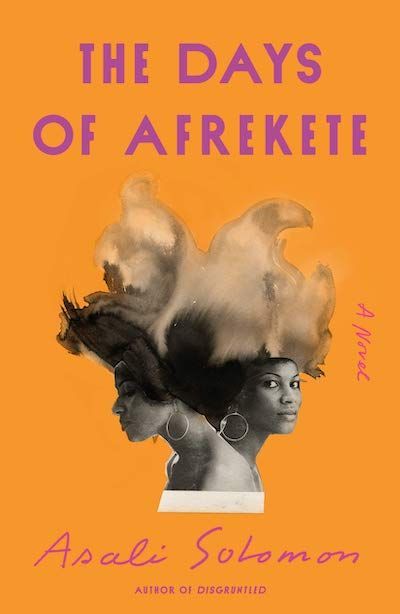

The Days of Afrekete by Asali Solomon. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 208 pages.

THE DAY I MOVED to Philadelphia, a large white van drove into my small, black car, which was parked outside my new apartment. The move had been prompted by my partner’s work; I was feeling guilty about taking a job (reluctantly, out of necessity) with an organization that was arguably leading the charge in privatizing the city’s beleaguered public schools. The van, as it turned out, belonged to the School District of Philadelphia. The driver (an older Black man) explained to me (a younger white woman) that he had fallen asleep at the wheel. I nodded and sadly assessed the damage to my modest, but new, Japanese car. The crash was not exactly propulsive — the man and I did not become friends, nor did I leave my questionable charter-school job. I simply became mired in the bureaucracy of the local school district and their whimsical approach to vehicle insurance. But the sickening crush of fiberglass outside my window, and the chaos that followed, became symbolic for me, in the six years in which I lived and worked in Philadelphia, of the city’s way of thrusting together wildly disparate people amid scarce resources, and forcing them to scramble through the ensuing squall. By day, I siphoned resources away from the school district, albeit indirectly; after work, I called their offices and begged them to cover my repairs.

The mess of America’s “poorest big city” — its tangled systems, its established aristocracy, and the miserable way in which its public institutions have been defunded and its Black and brown communities disregarded — begs for interpretation. Over the past few years, several novels have attempted some such interpretation, or at least made use of Philadelphia’s particular brand of racially and economically diverse disarray.

Kiley Reid’s Such a Fun Age became a best seller when it was published in 2019; its story of a young Black babysitter wrongly accused by police in a tony Center City grocery store of kidnapping the white toddler in her charge was a featured selection of Reese Witherspoon’s book club. Reid’s novel, while squirmily accurate in its depiction of the eagerness of a certain type of white folks to gain proximity to and curry favor with Black people, is a strange combination of the madcap and the static. Its characters, both white and Black, seem two-dimensional and inexplicable, all while making what can politely be described as questionable choices. Christine Pride and Jo Piazza’s We Are Not Like Them (2021) traffics in similar themes — female friendship, racial bias in policing, interracial dating relationships, white folly, motherhood — with a greater sense of compassion, if not much more nuance. The tale of a lifelong friendship between a Black reporter and the white wife of a police officer who kills an unarmed Black teenager, it was a pick for Good Morning America’s book club. These are the middlebrow entries in a new genre: the Philadelphia Novel, stories characterized by a tangle of law enforcement, alternating points of view, and romances between Black women and uninspired white men. (For the record, Reid and Pride are Black; Piazza is white.)

Asali Solomon’s new novel, The Days of Afrekete, is the latest entry in this genre. But Solomon’s slender dinner-party story is a more graceful and compelling effort, portraying this complicated city with an eye that is both tender and cutting. Liselle, a teacher at one of Philly’s numerous Quaker private schools, is married to Winn, a lawyer with political ambitions. Liselle is Black, raised in working-class West Philadelphia; Winn is white, and WASPy, an outsider who has made Philly his home. Liselle is throwing a dinner party, ostensibly to thank those who supported Winn in his unsuccessful bid for public office. But amid her goat cheese and her flowers, she is in turmoil: a handsome Black FBI agent has told her that Winn might be facing corruption charges. Federal agents could appear at any moment.

Through Liselle’s eyes, Solomon — who is also Black, and a born-and-raised Philadelphian — deftly sketches, and lampoons, the city’s moneyed class: the vaguely progressive, largely white, bourgeois residents of tastefully urban areas like Mt. Airy and Chestnut Hill. (Winn, attempting gratitude at the party: “I don’t know [Obama pause] what my future holds [pause] but I do know [pause] I want to see all of you in it.”) But while Liselle is “[d]izzy with alienation,” she is also skittering with worry about her family’s future and the potential for humiliation in the FBI’s looming charges. Underneath this unhappy blend of fear, anger, and regret, she finds herself returning to thoughts of Selena, a college girlfriend with whom she had a brief, intense relationship during her senior year at Bryn Mawr. (Bryn Mawr, one of several elite liberal arts colleges just outside the city, is a women’s school where Black students make up less than 10 percent of the undergraduate student body.) In a move that Liselle herself characterizes as “odd, sentimental, and desperate,” she calls Selena’s family home, identifying herself as “Afrekete” to Selena’s mother, who takes the message. (The name is an Audre Lorde–inspired code word between Selena and Liselle, employed to indicate that one of them was “about to punch somebody” at their Bryn Mawr feminist book group.) The dinner party, and Liselle’s life, lurch forward.

By her own admission, Liselle “has never had [her mother’s] easy way with regular Black folks. First she had been shy, then she’d been a lesbian. Now she lived in a big house in Mt. Airy with Winn, and spent most of her time with white people and [her son].” Their marriage is one of the more confounding elements of Solomon’s story, and perhaps its starkest parallel to the stories of Reid and Pride and Piazza. How Liselle — Black, queer, ambitious — came to find herself married to Winn, and how she became someone now characterized as a “gracious hostess,” is a question that the novel takes seriously, even if it does not provide an entirely satisfactory answer. Suffice to say: Liselle is adrift — personally, professionally — in a sea of whiteness. But if whiteness and its discontents give the plot its propulsive momentum, Black love is at the novel’s emotional center. Perhaps this — as well as Solomon’s sharp, funny, unadorned prose — is what lifts The Days of Afrekete above the fray.

The novel’s success rests on its coupling of a wide social lens and a delicately interior perspective. Solomon has made explicit the novel’s debt to Mrs. Dalloway, but it seems to draw, too, from the The Age of Innocence. Flipping between accounts of Liselle’s party prep, Selena’s day-to-day routines (the stabilizing structures she has built to avoid annihilation by mental illness), and the women’s brief courtship and its aftermath, the novel creates two delicate, miniature portraits of Black womanhood, and a tender, scrutinizing snapshot of an intimate relationship. It brings us into Philadelphia’s neighborhoods and among its residents, and into the dinner party that draws some of these people together. It is also a reflection on compromise: those that cities make, those necessitated by the pursuit of precarious sanity, those required by marriage and financial stability. But it’s also a deeply romantic love story about people who find one another in a landscape in which they are both made to feel out of place (in their Blackness, their queerness), and about the fragility and power of an intimacy that emerges out of alienation.

In its tangled engagement with a city that Liselle’s estranged father describes as “gray and sad and segregated,” the novel is perhaps closest to Liz Moore’s beautiful and harrowing thriller Long Bright River (2020). Moore’s novel, which similarly employs Philadelphia as both character and setting, plays with readers’ ideas about the integrity of police forces, and about the cultural tendency to typecast Black men as aggressors and criminals. It is similarly adept in its handling of class and its rendering of the painful divisions between people who might want — or need — to connect with one another, and the connections that endure between disparate types. Like Solomon’s novel, it is a love story. Moore is white; her protagonist, Mickey, a white cop in one of Philly’s hardest-hit neighborhoods, loves her young son and her sister, an addict, in ways that are fraught, fierce, tender, and alarmingly resonant. Where Solomon is able to capture the ways in which two young people cloister themselves and create a world of intellectual and emotional separateness, Moore shows how love can make one afraid of the city’s seemingly infinite capacity to harm. (“I’m lucky to have you,” Mickey tells her four-year-old. “‘Do you know that?’ Saying it aloud — even acknowledging my gratefulness for Thomas too frequently in my thoughts — seems to me to be a kind of jinx, an invitation, an open window through which some creature might come in the night and spirit him away.”)

In Solomon’s novel, there is always a sense of this dangerous city just outside Liselle’s house, pressing uncomfortably to get in. The FBI. The panhandlers whose needs fluster her. And the tantalizing — and terrifyingly disruptive — possibility of Selena. Her party guests, who traipse noisily into her gracious home, could be colluding with her husband in criminal ways; they could be informants, tipping Liselle’s wine down their throats as they plot Winn’s demise. By the end of the novel, it is impossible not to be terrified of whomever might next ring the doorbell.

Liselle’s stability is tenuous: a door can always be breached. Selena, plagued by the evils of the world, has a history of serious mental illness and institutionalization. At her worst, she lies awake fretting over Christopher Columbus, the cruelty of the settlers’ treatment of indigenous peoples, plantation slavery, contemporary child abuse: the horrors of whiteness. These preoccupations keep her from being whole, and at arm’s length from Liselle. Liselle, whose reluctant respectability is, by the time of the dinner party, an entrenched fact, spends her early adulthood dogged by loneliness and depression. In her established middle age, she sees the precarity of her situation: “[T]he sight of every unhoused, insane, uncared-for Black woman chipped away at her.”

The Days of Afrekete is, ultimately, terribly romantic. Rather than muse for too long on the ways that people betray one another, knowingly or unthinkingly, Solomon focuses on the enduring magnetism of young love, feeling seen by and connected to someone in a world that can be threatening and cruel. While it examines the compromises that one makes in the name of frugality and stability, it takes as its central theme the limitless possibilities that love allows. Philadelphia is part of what makes this possible. Solomon draws the city’s mess deftly, but she finds in it a romance: a story of Black love, of two women perpetually tossed by rough seas, and their fragile togetherness. She fashions them a delicate, breakable raft.

In early 2020, my partner accepted a job that would eventually carry us away from Philadelphia. I read the first of these Philly novels with an eye toward our exit, curious how they depicted a place that would soon be my past, rather than a pulsing, ever-changing present. One morning, on my way to work (by that point I had left my charter school job for another problematic sector), I drove through the streets of Mantua, a neighborhood toward which those in power seem indifferent except as a potential site of gentrification. The residential streets are pocked with empty lots, and the rowhouses that remain vary in condition: some have fallen into dramatic disrepair, some are tidily maintained, others have been spruced up by developers with a craven eye toward opportunity and cash. My car made its way down a street clustered with these low houses and emerged at the open edge of the Schuylkill River, in full view of the trim boathouses and the ostentatious neoclassical pile that is the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The juxtaposition of peeling, painted brick and rushing water and satellite dishes and vinyl siding and soaring columns and the mythological creatures that flank the museum’s roof was too much: I burst into white-lady tears. Perhaps I was primed to fall for a Philly love story.

One year later, in April 2021, the pandemic, which had brutalized Philadelphia’s Black community — disproportionately killing its residents, flooding the hospitals that remained after reckless closures, shuttering its schools and stores and restaurants — was in full swing. News broke that two local Ivy League schools — the University of Pennsylvania and Princeton — had been making exploitative use of the remains of two children killed in the 1985 city-sanctioned bombing of the MOVE Collective, a Black liberation group. Eleven people died in the bombing, five of them children. Philadelphians’ rage at this discovery was palpable, and fully warranted; protestors took to the streets outside my home in West Philadelphia, and the health commissioner was forced to resign. Our movers already booked, I marveled at the cruelty of the city’s institutions. I was a white interloper — like Winn, or Reid’s debased would-be white savior, Alix — leaving something messy to which I had become deeply attached, in which I felt painfully invested. By this time, I had traded in my old car for something larger and more durable, my apartment for a house. I was grief-stricken — I wanted better for my adopted city — but Philly didn’t care if I stayed or went.

Selena, spiraling toward a breakdown, tells Liselle that the Bryn Mawr library contains no record of the MOVE bombing — that any mention of it has been removed from the microfilm. This isn’t true, as it turns out: Selena’s encroaching madness tend to flatten the facts, render stark what is frighteningly complex. Despite its aggressive whiteness, the college library does contain the legacy of the MOVE bombing, just as it introduced Liselle and Selena to writers like Audre Lorde, and to each other.

While the Philadelphia novel of the early 2020s strongly engages issues of race and race relations, what does the genre make of class structures and struggles? Like Solomon’s earlier work — her 2015 novel, Disgruntled, and her debut collection of stories, Get Down (2006), both set in Philadelphia — The Days of Afrekete is careful not to generalize when it comes to the intersections of race, socioeconomics, education, and politics. Liselle’s and Selena’s financial backgrounds are different — one working class, one middle class — even as they both arrive at Bryn Mawr from neighborhoods in West Philly. Nor is the hierarchy within Liselle’s domestic sphere obvious or stable. The Latinx woman who cleans her house sends her daughter Xochitl, a PhD student and activist who confounds Liselle, to help with the dinner party. Around the pair, Liselle “felt her ever twoness as the Black mistress of a tiny plantation.” Nothing is easy. Nothing is pat.

Equally thoughtful is Moore’s exploration in Long Bright River of education as a slippery escape from the white working class. While Pride and Piazza do not seem to take much care with these class questions, they do make a point of subverting stereotypes around education and money: the two protagonists grow up in the same working-class neighborhood, but Riley is glossily upwardly mobile while her white counterpart, Jen, flounders in debt.

Solomon offers no sweeping sound bite, just a detailed snapshot of the way money twists and turns around race in a single city. Nor does she offer readers a handy take on interracial marriage, on what happens when Black worlds collide with — and threaten to be engulfed by — white worlds. Instead of the explosive conflict of Such a Fun Age, or the tragic abuses and misunderstandings (and corresponding olive branches) offered by We Are Not Like Them, Solomon simply draws a picture of two Black women, and the ways in which whiteness simultaneously offers them shiny gifts and squeezes the air out of their lives. “At times,” Solomon writes, “Liselle remembered being waited on by tuxedoed white servers at Le Bec-Fin at her first wedding anniversary, the heavy gleaming silver dessert cart. She thought about how the ability to select and eat a confection from that cart made her part of something not larger, but smaller.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Miranda Featherstone is a writer and social worker. Her essays have appeared in The New York Times, The Yale Review, and The Virginia Quarterly Review. She lives in Rhode Island.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Holding and Unfolding Woolf’s Treasure: On “The Annotated Mrs. Dalloway”

An indispensable critical guide to Virginia Woolf’s masterpiece.

How “Such a Fun Age” Came to Be: An Interview with Kiley Reid

Jabeen Akhtar talks to author Kiley Reid about her debut novel, “Such a Fun Age.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!