Big Sur Attracts People Who Are Seeking Something: A Conversation with Lexi Kent-Monning

Brian Frank speaks with Lexi Kent-Monning about her new novel “The Burden of Joy.”

By Brian Charles FrankNovember 11, 2023

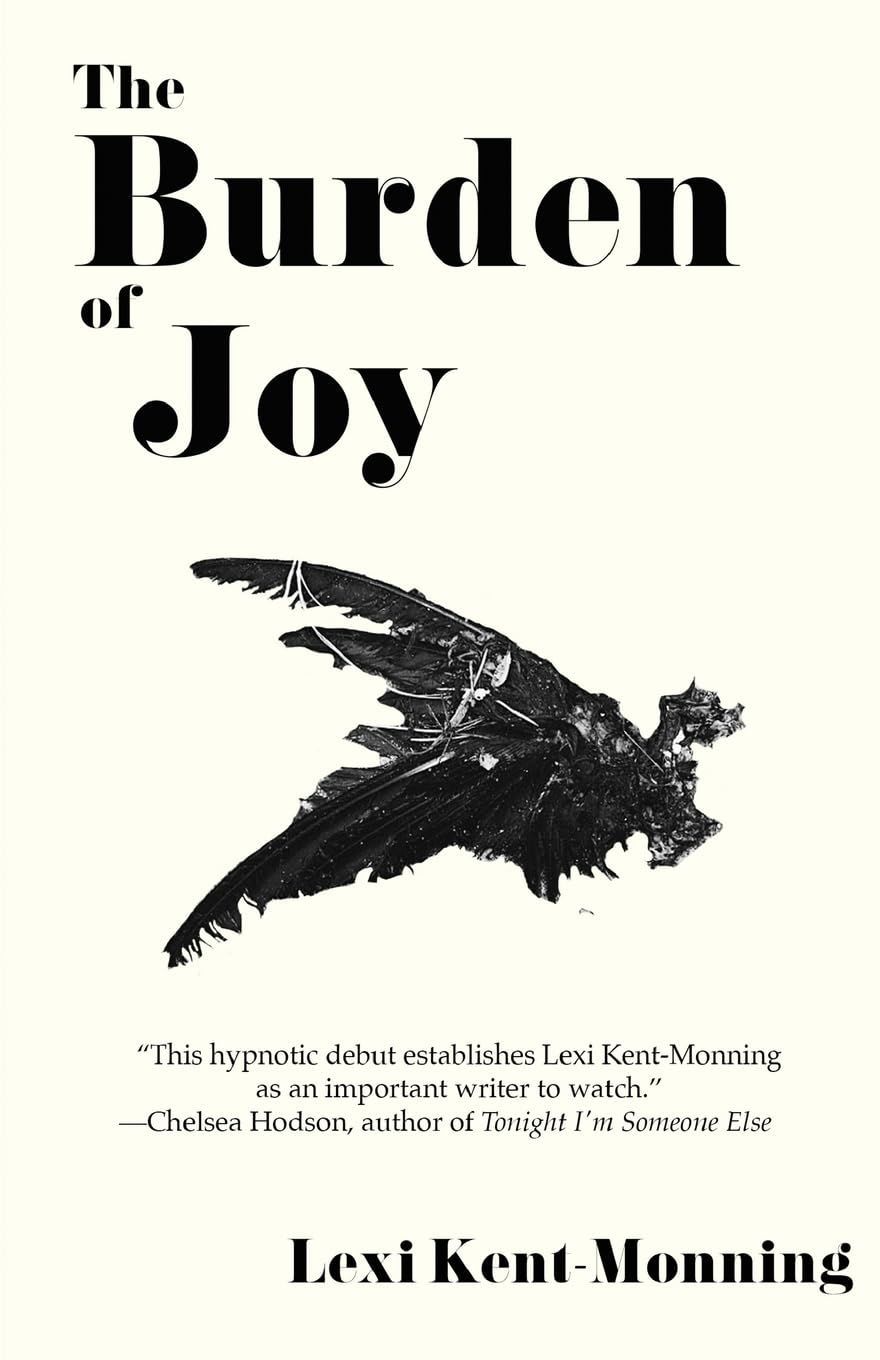

The Burden of Joy by Lexi Kent-Monning. Rejection Letters. 204 pages.

IN LITERATURE AND popular imagination, Big Sur is the glamorous ideal of California, an untamed Eden. Just check Instagram. Or ask Henry Miller, who wrote: “This is the California that men dreamed of years ago, this is the Pacific that Balboa looked out on from the peak of Darien, this is the face of the earth as the Creator intended it to look.” Big Sur is where the California Dream is most vibrant and uninhibited but also the most on edge.

Lexi Kent-Monning’s stunning debut novel The Burden of Joy (2023) is a tragicomedy about a marriage falling apart on the jagged rocks of Big Sur. The narrator, Lexi, and her husband, Daniel, leave Los Angeles for the wild coast, where he gets his “dream job” at a commune (which feels a lot like the famed Esalen Institute, though it is never named in the book).

Lexi loses her husband to the hot springs, art yurts, and sexual freedom of the area, while the landscape itself seems to turn against her. “I began stumbling upon the dead almost daily,” she says about the succession of animals she finds. A bridge on Highway 1 fails, isolating her further from Daniel. He gets a new commune name, “The Oracle,” and their distance grows spiritually, physically, morally. “I begged for the Bixby Bridge to crack under my tires and swallow me, for a landslide to expel me from the mountains into the sea.”

Eden lost, she must mutate to evolve. In the second part of the book, Lexi finds her hunger for life renewed in New York City in a relationship with a new lover, Leo, but this change comes with its own isolations, and eventually some hard-earned enlightenment.

I first encountered Lexi Kent-Monning’s voice in hilarious short works, but this book, which the author dubs autofiction, is something else: deeply personal, philosophical, and visceral, yet still funny and hopeful. I talked with her over Zoom on Labor Day from her home in Brooklyn.

¤

BRIAN CHARLES FRANK: You grew up in Salinas—Steinbeck country—and your narrator talks about having “Big Sur in her bones.” Have you always wanted to write about Big Sur?

LEXI KENT-MONNING: When I was growing up, Big Sur was so mythical—we would go camping there every summer—the lore of all these bohemians who went through there at some point, and the funky little restaurants and just the coastal beauty, compared to Salinas. Salinas smells like fertilizer and there’s crops everywhere, and it’s funny—to me, that is so “home.” When I smell fertilizer, I get homesick.

In my thirties, I ended up moving back to the Carmel Highlands, which is right at the mouth of Big Sur. It’s such an evocative place for me that I almost felt like I didn’t have a choice. I just had to start there.

And when you were living there, were you thinking of a novel?

I never intended to write it as a book. In the beginning, it was just therapeutic. I did actually start finding dead animals and a bridge literally fell down between the Daniel character and my character, and it all seemed too strange to ignore. I never would have used such a shitty metaphor, but because it was really happening, I had to write through it to try to make sense of it, or just to record that it was truly happening to me, that it wasn’t my imagination.

It started to form into something else when I applied to go to a writing workshop in Italy with Giancarlo DiTrapano and Chelsea Hodson, and they needed a 20-page writing sample. And I thought, well, I guess I can gather these scraps and make it into something cohesive. It might be just a journal that never ends up seeing the light of day. Then I got accepted, and I needed to bring 50 pages with me to the workshop. I brought all these fragments, and my whole cohort there really encouraged me to continue with it. And so it kind of unintentionally ended up being book-length.

And the structure of the book is interesting: it jumps between times …

Once I had all the fragments, I could start to see themes coming up and spot patterns. I thought I could jump around a little bit in time and in place as long as I had some of these themes that I kept coming back to, to ground the reader. So certainly Dead Animals and Colors and Big Sur and a Sense of Home were things that I just kept coming back to.

The writer Paul Beatty said recently about the geography of Los Angeles fiction: “[A]ll these LA books, including mine, are fundamentally about loneliness.” Reading your book, I wondered if all Big Sur novels are fundamentally about isolation?

Yeah, I think Big Sur really attracts people who are trying to find something. And some people, it just really exacerbates their loneliness, or they’re seeking something and they don’t find what they’re hoping to find. And then especially, during the time I was living there when the Pfeiffer Canyon Bridge broke [due to landslides in 2017], it created a true island, and then there was such a huge sense of isolation. I wasn’t stranded in that weird island that Big Sur became with no way in or out. But the person I wanted was on that island, so I felt so removed.

But what you’re asking about the novels, it’s true. I think Big Sur attracts people who are seeking something, and I think a lot of writers write towards what they’re seeking.

Speaking of writers, the area has a weighty literary history. Henry Miller, Jack Kerouac, Hunter S. Thompson, Richard Brautigan, etc. First of all, why do so many dudes write about Big Sur?

Yeah, I know, right? Where are the women?

Were you thinking about these books when you were writing?

I was definitely thinking about Henry Miller while I was writing it. And part of that was because he had a presence in the place I was living. When he lived in Big Sur, he used to visit friends in that actual cabin where I was staying, and even got married there. And my godmother, who lived next door, she would always tell a story about “Henry.” And I’d be like, “Are you talking about Henry Miller?” And she’d say, “Oh yeah.” So, whether I wanted him to be present or not during the writing of it, he totally was. So I did end up going back and reading Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch (1957) multiple times when I was living in that spot.

The other ones less so … but I’m a major Brautigan fan. I think he’s my favorite writer. I adore him. And I kind of intentionally didn’t read him during the time I was writing this. And then when I was done, I did a deep dive right back. I was feeling like I missed him.

There’s also an otherworldly vibe around Big Sur. Certain times when I was reading your book, it felt like I was in a Brontë sisters novel. Except, instead of roaming across the moors, your narrator is walking her dog through the woods and the reader’s just afraid of what she’s going to find next. Do you think Big Sur is haunted?

I don’t think it’s necessarily haunted. But I do think that just the structure of the geography there makes it seem like that. There’s always something biblical happening. There’s always “the biggest storm or landslide” in 100 years. I mean, I guess that’s a lot of California now.

But speaking of the vibe, it reminds me of another big inspiration point for me. I love Nine Inch Nails. They’re my favorite band. I’m obsessed with Trent Reznor. He moved to Big Sur for a while to write a record and only came away with one song called “La Mer,” which is on his 1999 double record The Fragile, and I listened to that song constantly, when I was writing the book, when I was living in Carmel Highlands in that cabin, and I would just drive into Big Sur until I got to the broken bridge and would have to turn around; I would listen to that song on repeat over and over. And it’s almost entirely instrumental. There’s three lines of lyrics, but they’re in French, but it is so evocative of Big Sur, and knowing that he wrote it sitting on those same cliffs, watching the same ocean … There’s this weird tension in that song, where it feels kind of desperate but then kind of hopeful, and I wanted the book to feel that way too.

Reinvention is another big theme of California stories, and in your book, Daniel is able to become The Oracle at the commune, but it’s not always so easy for Lexi.

It’s interesting to me that the goal for Daniel was “I just have to put in all my time and working all these crazy jobs and sacrificing so much of my life, but I’ll eventually earn getting to live in Big Sur.” And then, once he does feel like he’s earned it, he becomes The Oracle and he thinks, I’ve made it. This is it. But I have to cast away everything that reminds me of my previous life.

And Lexi is trying to catch up with stuff all the time. Life is happening to her instead of her deciding what’s going to happen. She’s always in a reactive position, and I think that can make it a lot harder to reinvent yourself. She was trying to help Daniel achieve his life. And then, once he does, she’s like, “Oh shit, now what about my life? I didn’t think about that. I forgot about me.”

But she does eventually mutate when she ends up up with Leo in New York. In fact, her eyes literally change color …

I genuinely thought that happened to me at one point. I thought, “Oh my God, my eyes look green. This is so crazy. I thought they were blue my whole life.” I genuinely thought that because I was so under the illusion of love.

So I think, for me, that mutation for the character is kind of a flawed or failed endeavor because she thinks that she has reinvented herself but it’s really just the influence of another man in her life. It’s just this hollow premise.

And so it was fun to write the epilogue and kind of poke fun at myself: “Oh yeah, my eyes changed color.” Like I had solved everything and I wanted that to be visible to other people. And it never will be until you actually make the changes yourself and aren’t just influenced by someone else.

I found the New York parts of the book very unique, because Lexi and Leo don’t really exist in public spaces like in most New York stories.

I’m glad that that came through, the feeling of kind of claustrophobia, of being in an enclosed space with somebody. It’s based on a real feeling of that relationship for me. We were always altered somehow, whether it was drugs or sex or whatever, it was this total nonreality where we wouldn’t even go out, we would call in sick to work because we didn’t want to leave that little space.

There’s a hedonistic aspect of nurturing for the Lexi character, in relation to both Daniel and Leo. At one point, you write, “There’s selfishness in my selflessness.”

I think a big part of of the retrospective for me of the Daniel relationship while I was writing it was realizing how often I was making things happen almost like a parent. Like you’re setting your kid up for success, you’re getting them ready to go to soccer practice or whatever it is. And then it extended itself to being a personal assistant for people, which I did in Los Angeles in my twenties. And that’s like you’re someone’s parent, basically—not to infantilize the people who I did that for, but—you know, making sure that someone’s wearing the right thing, they’ve used the bathroom, they’ve eaten something, they’re somewhere on time. So much of that stuff seems so maternal. And so only in writing this book did I start to deal with that.

And I was thinking: Why do I do this for other people? I started to realize that it’s what makes me feel validated. It’s what makes me feel good and it comes naturally to me. And so I started to feel like I get this high from doing this, and taking care of somebody else would start to feel like taking MDMA—I feel fucking great, this feels awesome.

And so I definitely leaned into that with the Leo relationship too, because that was even more so than it was with the Daniel character. Leo’s thing was that he was such a hedonist. And I thought that was great. He’s always going to need someone to take care of him because he’s always going to be calling at five in the morning and being like, “I don’t know how to get home,” or whatever it is.

Right, and it reminds me of one of the funniest bits in the book to me, when Leo tells Lexi they should fuck a couple, because “you’re such a nurturer, you’d be the perfect swinger.”

Yeah, because he means it so seriously. Like at the commune also, with Daniel, there would be things that I just thought were so funny, and other people took them so seriously. And so I think I tried to portray that in my description of it, of this place that is so surreal and so absurd, and I just need people to know how crazy it is. And I wanted some moments of levity in there because it’s pretty dark the whole way through.

I think you came to writing somewhat later later in life; is that true?

I always loved writing. I grew up in a major reading family. My grandma was an English teacher, so it was just always part of my life. I never thought it could be a big focus of my life for some reason. I think partially because it was the one thing anyone told me I was good at. And I thought, Oh well, then I can’t fuck it up. So I can’t pursue it. What if I’m bad? What if I try it in earnest and I suck at it?

I worked in the music industry, and being a personal assistant in L.A. And I always kind of secretly wrote and I always read a ton of stuff. But I started taking it more seriously and learning about the literary scene and indie lit magazines, I think a year before I got divorced. I started working a remote job that allowed for a lot more time and space for creativity. Then I got divorced and this book just came out of me, and going to that writing workshop in Italy was huge. I felt like that just uncorked me, and I’ve just been writing with urgency ever since, so that was a life-changing thing for me. I still have a job and I like having a job and not having to worry about the finances of making money from art.

¤

Lexi Kent-Monning is an alumna of the Tyrant Books workshop Mors Tua Vita Mea in Sezze Romano, Italy. Her work has been published in XRAY, Joyland, Tilted House Review, Neutral Spaces, Little Engines, Words & Sports Quarterly, and elsewhere.

LARB Contributor

Brian Charles Frank (a.k.a. BF O’Gnarly) is a Los Angeles–based writer and musician who wrote the original story for the independent movie/cult classic Hesher (2010) with Natalie Portman and Joseph Gordon-Levitt. He has written travel books, commercials, songs, and a forthcoming novel, due in 2024.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Refuge Through Insurrection: On M. E. O’Brien and Eman Abdelhadi’s “Everything for Everyone”

Shinjini Dey reviews M. E. O’Brien and Eman Abdelhadi’s “Everything for Everyone.”

On Autotheory and Autofiction: Staking Genre

Teresa Carmody deliberates upon the feminist histories and radical possibilities of autotheory and autofiction.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!