Beyond the Bathroom: Centering and Affirming Non-Binary Trans Perspectives in Heath Fogg Davis’s “Beyond Trans: Does Gender Matter?”

Jacob Lau on “Beyond Trans: Does Gender Matter?” and the importance of challenging the sex-discrimination regime at its administrative heart.

By Jacob LauOctober 22, 2017

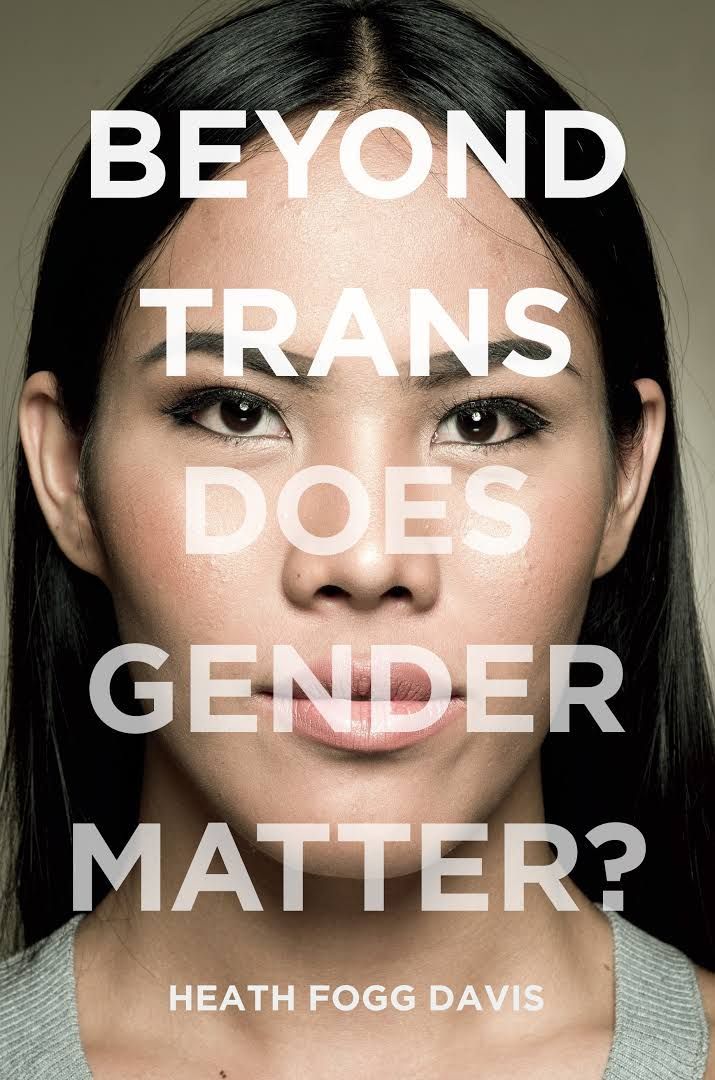

Beyond Trans by Heath Fogg Davis. NYU Press. 208 pages.

AT FIRST GLANCE, the title of political theorist Heath Fogg Davis’s new monograph Beyond Trans: Does Gender Matter? seems like an anti-feminist screed or a call for a post-trans rejection of gender as a schema for identity. The mistaken, latter reading would treat transgender as an outdated identity shot through with its own normative set of assumptions about the interface between identity, narrative, and gendered embodiment. This vision of transgender identity harkens back to the early 2000s’ call for an anti-identity politics, one that posited a kind of cultural utopia outside structural racism, sexism, and heterosexism. The politics readers might misidentify in Davis’s red herring title crystalized in arguments that, after the election of the United States’s first black and mixed-race president, Barack Obama, America had entered a post-racial moment. An analogous post-trans identity would insist on a similar irrelevance of gender to suggest that sexism is a structural problem of the past. Davis has no such illusions that we are in or even anywhere near such a moment.

Beyond Trans’s short answer of the title’s question is yes, of course gender matters, in part because systemic oppressions have not disappeared. However, Davis makes a thoroughly convincing case that what he terms “sex classification policies,” which bolster sex-identity discrimination by regulating gender, should not matter. Davis identifies sex-identity discrimination — the ways in which people are gendered according to the male/female binary — as a subcategory of sexism. Sex classification policies, thus, are informal and institutionalized ways in which sex-identity discrimination takes place in our everyday, routinized life: checking a sex-identity box on an employment application or policing who may enter the men’s or women’s restroom. In the book’s introduction, Davis asks if we might stop “trying to assimilate” transgender people into the binary regime of sex-classification policies and instead “tackle the genesis of ‘transgender discrimination’ — sex classification, itself.” That shift moves the conversation to the much more fundamental question of how and why we administrate sex as an identity category at almost every juncture of our lives. Liberalist equality, a strategy taken by the mainstream transgender civil rights movement (among others), prioritizes assimilation and accommodation into extant systems of binary sex-classification. This approach centers the idea that changing policies to explicitly allow trans people access to sex-segregated spaces and correcting identity documents to reflect their gender identity will prevent discrimination or at least make trans people feel more welcome.

However, Davis contests liberal equality for not going far enough to prevent discrimination, and for failing to address the architecture of binary sex-classification that still remains intact. Davis reframes the failings of liberalist equality, outlining in practical terms how to assess and remove the administration of sex across identity documents, bathrooms, college admissions, and athletics. Arguing that there are more pertinent ways to classify bodies and verify identities than sex and gender, Davis recounts the ways that medical, legal, and social science have thoroughly debunked the myth of sex and gender as immutable characteristics. In doing so, Beyond Trans avoids the intellectual quagmire through which discussions about trans identity and the official administration of trans people often devolve, as I’ve witnessed many times as a transgender professor and recently finished PhD. I highlight these potential misreadings of Davis’s book (for those judging simply by the cover), because they are sure to arise given the systemic social, cultural, and political investment in the gender binary. Even with the recent rediscovery of the profitability of trans narratives, bodies, and lives in mass media, it seems there are some stories we just can’t stop telling ourselves and this, too, is what Davis puts to critique.

In moving beyond those narratives, Beyond Trans points to what I see as the future of Transgender and Gender Studies as academic fields: centering the needs and concerns of non-binary people, whether or not they are trans identified. Despite purporting to challenge the gender binary when the field emerged in the 1990s, trans studies has often focused on affirming trans women or men (as well as trans masculine or trans feminine folks) in their respective genders from the perch of a cisnormative ivory tower that often neglects the experiences of gender nonconforming, genderqueer, and non-binary trans people. In order to push non-binary and gender nonconforming perspectives to the heart of trans politics, Davis outlines the history of reading racialized gender and sexuality as nonnormative as a way of containing and administering the bodies of people of color. Davis recalls Khadijah Farmer’s 2007 case against Caliente Cab bar and restaurant for being thrown out of the women’s restroom by a bouncer who misgendered the black masculine lesbian as a man. Despite telling the bouncer that she was in the correct restroom, and having an identity document that listed her as female, Farmer was thrown out. Davis uses this case study to suggest that what really happened that night was that Farmer “had violated heteronormative standards of femininity” but also that she had violated the norms of a racist society.

Davis writes:

When Farmer was accused of being a man in a women’s restroom, she was more pointedly accused of being a black man in a women’s restroom. Even more pointedly, she was accused of being a young dark-skinned black man who was deemed threatening and out of place in a female-marked public space.

When the Transgender Legal Defense Fund filed a lawsuit on behalf of Farmer, they cited Caliente Cab for illegally discriminating against Farmer’s sexual orientation and gender expression, but as Davis notes, these were simultaneously compounded by the ways the bouncers and clientele of the restaurant read Farmer’s gender and assumed sex through her race and darker skin tone.

In such moments, Davis’s engagement with questions of race and sex undergirds the imperative of thinking beyond the importance of sex to administrative documentation. Expanding on Farmer’s case, Davis claims that “[s]ex-identity discrimination is about intersectional sexual affinity, about where and with whom we belong in the racialized social scheme of sex.” The culture of gender policing in restrooms — particularly the rhetoric around privacy, cleanliness, and safety — have roots in prioritizing the comfort of those privileged by race, class, and gender-conformity. Davis gives the example of white women workers participating in labor strikes during the 1950s against workplace integration because they would have to share bathrooms with black women, whom they believed would pass them syphilis via towels and toilet seats. Thinking the history of sex-identity discrimination through its intersection with the history of race discrimination, Beyond Trans aligns with a long genealogy of women of color feminist political thought that remains central to contemporary political discourse.

Davis demonstrates that not only are the oft-cited reasons for federally mandated data collection of sex demographics based on the outdated and inaccurate belief that sex (and the assumption of gender from sex assigned at birth) is immutable and monolithic, but the sacrosanct place of birth certificates in the cultural and political imagination renders trans, gender nonconforming, and intersex people as exceptional citizens. This discourse of exception frames such individuals as needing accommodation within the gender binary so that they may be assimilated into the sex-segregated practices, spaces, and institutions inscribed by it. The burden of proof falls on the individual trans person to qualify for exceptional status in order to be accommodated and/or assimilated within binary venues with no regard to the ways in which inconsistent policies regarding sex and gender in administrative forms and procedures render them an at-best fraught, and often dangerous, experience for trans people. National attention to this issues has usually focused on the case of trans students who want to use a bathroom corresponding with their gender identity. What often gets left out of media coverage is how these students rely on the acceptance of guardians, parent(s), and school officials to lobby for their admittance to a gendered restroom. Davis claims that this state of affairs puts trans students in a precarious position, reliant on a politics of respectability in terms of being white (the documented cases are mostly of white students wanting admittance to one binary restroom), adhering to middle-class niceties, and citing the gender norms of that student’s gender identity. As Davis asks:

How will the school district handle a case in which a student self-identifies as neither male or female, or as both male and female? Or, to follow the logic of the case, would the case have been so compelling, and clearly seen as sex discrimination, if the transgender student had not been accepted as male by his parents, teachers, and classmates? Would school officials have reacted differently if the transgender student had been black, working class, and/or poor?

In order to be exceptional and therefore easier to accommodate and assimilate within a binary structure, the onus of doing gender correctly means being respectable within a normative framework of manhood or womanhood.

In addition to its imbrication with histories of race discrimination, Davis also explores the history of sex discrimination as part of the case he builds against the sex and gender administration of public life. Davis unpacks the ways in which patriarchal institutions were engineered to exclude women from social and political life in four areas: state identity documents, college admissions, public restrooms, and athletics. Historically, elite colleges and universities admitted white men only, leading to the founding of women’s colleges in a separate-but-equal formulation. Likewise, Victorian-era feminists had to organize for the inclusion of women’s public restrooms in schools, workplaces, and commercial spaces since public restrooms were then provided only for men. Similarly, the separate-but-equal logic organized women’s sports, which Davis demonstrates were molded into an imitation of men’s sports without questioning the sexism already at play in those institutions (and continues to play out in the sex-based justifications for lower salaries and worse playing conditions for women’s teams). This is familiar ground for students of gender and feminist studies introductory courses, but Davis’s work differs dramatically from past approaches to framing administrative practices and analyses of legal rhetoric from trans (especially non-binary) affirmative perspectives.

Rather than incorporating non-binary trans folks into a binaristic, cisnormative framework of sex, Davis historically contextualizes the integration of gender and sexually marginalized people into systemically exclusionary spaces, and particularly why liberalist approaches of assimilation and accommodation have fallen far short of what could have, and should have, been the goal: the removal of sex classification on administrative forms and identity documents, and the sexual desegregation of public space. Davis argues that, rather than equalize the playing field, moves to accommodate women effectively created a second-class version of male-designed spaces and institutions. One example is the lack of “potty parity” in restrooms: there are dramatically fewer stalls per restroom in women’s bathrooms than in the mix of stalls and utilitarian urinals in men’s restrooms. The separate-but-equal approach to integrate gender-marginalized people did not translate to equality for cisgender women and, unsurprisingly, this form of equality has not become equity as it has been extended to trans people. Even this paltry form of equality has shown itself to be increasingly out of reach since Trump took office in January.

Davis argues that instead of relying on reactive or proactive approaches to assimilate or accommodate trans people in sex-segregated spaces, the current moment offers an opportunity to dismantle sex and gender segregation. This would start by outlining a clear definition of sex or gender and its relevance to any intake form or application within an organization or institutional practice. Davis astutely argues that filling such line items on forms is confusing to the trans and/or gender nonconforming applicant or patient if it is not specified whether sex or gender is determined by what is on their identity documents (and, if so, which identity document: birth certificate, state identity card, social security, et cetera) or by the applicant or patient’s personal gender and/or sex identity, which may contract their identity documents. By putting pressure on why an organization or institution asks for sex identification information, we might see if a given sex-classification policy is rationally related to a legitimate policy or administrative goal.

Davis’s solution-oriented Beyond Trans is a necessary voice in current debates about the administration of sex and transgender identity. From the infamous bathroom bills to cis citizens’ objection to financing the medical expenses of trans military personnel (the specter of which Donald Trump backhandedly invoked during his transgender ban tweets), to women’s colleges determining that sex-segregation and defining the boundaries of womanhood were necessary to a feminist project of education, Davis’s book offers applicable solutions and applies the knowledge gained from the positionality of trans, intersex, and non-binary viewpoints. By reframing these debates and topics as new iterations of a larger structural problem (sex-identity discrimination) that has operated for years on gender nonconforming and trans people under the public radar, Davis puts to print what gender nonconforming, genderqueer, and non-binary trans folks have known all their lives, that what needs to be rethought and reworked is the purpose of such administrative systems. To that end, Davis includes a very practical gender audit for organizations interested in putting Davis’s suggestions into practice in the appendix. Davis’s tremendous efforts in Beyond Trans makes for both an exceptionally readable and engaging political salvo, and one immensely useful beyond the halls of academia.

¤

LARB Contributor

Jacob Lau is a University of California President’s Postdoctoral Fellow at University of California, Irvine. His work theorizes transgender through postcolonial, queer of color, and historical materialist theorizations of time and historicism. Along with Cameron Partridge, he is an editor of Dr. Laurence Michael Dillon’s 1962 trans memoir Out of the Ordinary: A Life of Spiritual and Gender Transitions, for which he also co-authored an introduction. Lau received his PhD in Gender Studies from UCLA, and holds a BA in English from UC Berkeley, as well as a MTS in Women, Gender, Sexuality, and Religion from Harvard Divinity School.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Gaming Gone Queer

A new collection of essays probes how queerness intersects with the video game as an industry and an art form.

When Being Counted Can Lead to Being Protected: Pakistan’s Transgender and Intersex Activists

Kyle Knight argues for the right of Pakistan’s transgender and intersex activists to be counted, and heard.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!