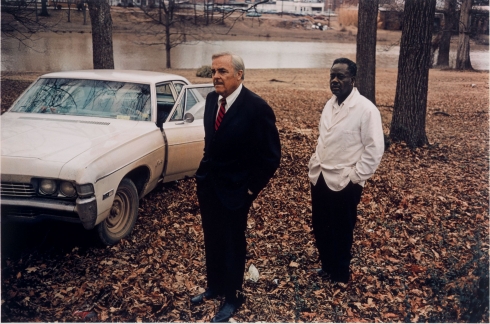

Image: William Eggleston, "Untitled," 1974

I WAS LATE FOR the start of William Eggleston’s signing session at Paris Photo Los Angeles, held at Paramount Studios earlier this year — though I wasn’t as late as William Eggleston. The signing was scheduled for 3 pm at the stand belonging to the Gagosian Gallery; I got there at about 3:20 (I had what I consider good reasons: I was watching Richard Misrach and John Divola in conversation, and it was hard to find the right moment to make an exit) and in any case my lateness didn’t seem to matter much since Eggleston was not in sight when I arrived, even though a lot of his fans were, lined up, snaking out the door.

Eggleston was coming to sign the “catalogue” for his Los Alamos show, seen at the Gagosian at the end of 2012, a fine exhibition containing some very familiar Eggleston images as well as some lesser known ones — a group of dolls sitting on the hood of a Cadillac, a Chevy Impala chained to a telegraph pole, a supermarket employee pushing a line of shopping carts; that last being one of the very first color pictures Eggleston ever took. But in reality, the thing he was signing was not so much a catalogue as a kind of boxed set, a black leatherette slipcase containing, as the bibliographic sources have it, “two sewn-bound folios, one with 10 vertically oriented plates and the introduction, another with 27 horizontally oriented plates, and an illustrated 16 page booklet with an essay by Mark Holborn.” And this was something of an issue for me. The fact is, I’m a collector of photography books, not on any grand, extravagant scale, but serious enough that I’m prepared to shell out $100 on the right volume — that indeed was the price of the Eggleston/Gagosian Los Alamos, but this catalogue wasn’t really a book. So I was thinking I probably wouldn’t buy one; I’d just go and gawk at Eggleston, a southern dandy and aristocrat, “the father of color photography,” and perhaps still a hell raiser at age 72.

But, since Eggleston wasn’t there, I went away and drank a cup of coffee, returning to the stand at about 10 to 4. The line had gone, but Eggleston was now in situ, behind a desk, still signing. And suddenly I thought, oh what the hell, I’ll buy the thing after all. I approached a Gagosian flunky and asked where I could pay my money, and she reeled back, faintly disgusted, and said I was far too late. Mr. Eggleston had been signing since 3:00, and he was tired out. Of course I was tempted to say, “Well he may be tired out, but it ain’t from signing since 3:00.” I knew he couldn’t have been signing for much more than half an hour, and just how tiring is that? But I held my tongue. I wasn’t going to cajole the Gagosian staff into taking my money, and there was some small satisfaction in knowing that I’d be making Larry Gagosian just a scintilla less rich. But I don’t think it was entirely sour grapes that made me decide I was better off without this Los Alamos catalogue: it really wouldn’t have fit within the parameters of my collection, and a collection is nothing without parameters.

¤

I know there are some who’d say I’m not much of a collector at all, and I wouldn’t give them an argument. I know enough about obsessive collectors to realize I don’t have the genetic makeup to be the genuine article. Martin Parr, for instance, the author with Gerry Badger of the two-volume The Photobook: A History, would no doubt think I was a complete trifler. I have stood with Parr in his air conditioned, humidity controlled, darkened book room, surrounded by his collection — literally priceless in that no amount of money would allow you to replicate it, given that some of the books in there are unique — and compared with him, I suspect nobody in the world is a real collector.

Still, many laymen would no doubt think I have way too many photography books and spend far too much money acquiring them. True, I do write about photography sometimes, so the books are a kind of reference library, though I started collecting long before I started writing. And much as I like the material nature of books, and appreciate books as objects, I would say (and I don’t think I’m deceiving myself) that it’s the contents that are important, not the form. Having said that, I do think that the best photography books are works of art in themselves.

I’d also argue that books are the very best way of looking at a photographer’s work, preferable to seeing them on a gallery wall, for instance. Of course the gallery print is likely to be more “authentic,” closer to the source, closer to the photographer’s intentions, and often signed and therefore touched by the artist’s hand. But equally, in a gallery the print is going to be behind glass, there’s going to be some twerp standing in front of it, blocking your view, perhaps expressing loud, dreary insights. And there are real limits to how long anybody can stand in a gallery looking at photographs, how many images you can really look at in a session without getting sated, without losing your concentration and judgment.

Looking at a book is a private rather than public experience. You have the book in your hands, in your home. You can look at it while sitting in a chair, at a table, in bed, in the bathroom. You can view a certain number of photographs, put the book aside, then later pick it up again, as and when you please. You live with the images, develop a personal and sustained relationship with them.

I know you could say that there’s something inauthentic about the book as opposed to a print, but the fact is that one way or another, most of the photographs we see are reproductions. We see them printed or scanned, and in an age of digital reproduction, it’s hard even to know what an original is. Increasingly we also see photographs, and find photographers for the first time, online, where you’re sacrificing quality for quantity: low res JPEGs really don’t tell the whole story, but I’m not dissing them. The first Eggleston images I ever saw — the fire in the barbecue grill, the glowing cocktail on the airplane tray table — were on postcards, and I snapped them up, and I wouldn’t say the experience was entirely ersatz.

As my experience at Paris Photo Los Angeles demonstrates, I’m not an Eggleston completist. In fact, it’s pretty much impossible to be a completist with any very well known photographer. Books published before they were famous tend to be rare, desirable, and expensive, and contemporary editions are often published with the collector market in mind: numbered, signed, limited editions, slipcases, sometimes with an extra print and what not. Neither of these categories is usually for me. Still, I do tend to have clusters of books by certain photographers I especially like, some of whose books come within my budget.

The main names are Eggleston, Martin Parr, and Garry Winogrand; a bit of a boy’s club to be sure, but quite a diverse bunch of boys: Eggleston the master of subversively Zen imagery; Parr the covert class warrior who began photographing the misery of the English seaside and now photographs the vacuity of the super rich; Winogrand the boy from the Bronx, the man of the street, the obsessive who took photographs even when there was apparently nothing to photograph. It’s Winogrand who offers the fewest books to collectors. He died in 1984, missing out on the international photography boom, and he published just four books within his lifetime. Martin Parr’s bibliography, by my reckoning, now stands at 58 volumes.

¤

The most obvious thing to notice in my, or any, collection of photography books is that they’re not what they used to be: they’re generally much better and certainly bigger. Not very long ago 100 or so images was considered more than enough to make a book.

Two of the first books I ever actively “collected,” as opposed to just bought, were by Martin Parr (I realized these purchases were in a different league when I very politely and no doubt very pushily — I was young and shameless — arranged a meeting with Parr at the ICA in London and got him to sign them for me): Bad Weather published in 1982 (pictures of English folk battling through rain and snow) and A Fair Day: Photographs from the West of Ireland from 1984 (Irish folk in pubs and ballrooms, and at horse fairs). They’re books I couldn’t possibly afford at their current prices. Each of them has just over 50 plates.

Robert Frank’s The Americans (1958), broadly considered the Ur-document of 20th century photography, has just 83 images: Frank supposedly shot 28,000. A later 2009 version of the book, accompanying a travelling exhibition and titled, rather clumsily if you ask me, Looking In: Robert Frank's The Americans, Expanded Edition added a great deal of critical and historical apparatus, but the images, with a few minor tweaks, remained unchanged. This book led Anthony Lane to write in The New Yorker, “Inside every fat volume, of course, a thin one is signaling quietly to get out.”

Back in the day, faced with these slim volumes, some of us certainly complained that they weren’t exactly great value. We wouldn’t have objected to getting a few more images for our money, but we accepted, grudgingly or otherwise, that we were in thrall to the economic realities of publishing. I don’t think many of us were crying out for (or even imagining) books like Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s Thousand — 1000 color plates, 2008 pages, or the Helmut Newton Sumo, 464 pages, 20 x 27.5 inches, and weighing 66 pounds — but we’re certainly glad they exist, even if we can scarcely afford them, or in the latter case, even lift it.

There has been a considerable trickle down effect; photography books with a couple 100 images are common, and they’ve become more affordable, if not exactly cheap. Mere mortals can actually afford to buy them, and if they still seem pricey, try buying a photographic print. Unless you have pockets of scarcely imaginable depth, you won’t be owning an original William Eggleston. A print of Memphis (Tricycle), the iconic image from the cover of William Eggleston’s Guide, a child’s trike photographed from bug’s eye level so that it towers over the ranch house and car behind it, sold at Christie’s in March 2012 for $578,500. A true first edition of Guide will set you back 1000 bucks or so, though a brand new copy of the currently available reprint can be had for less than 25.

¤

The collector of photography books might, in any case, think that the Gagosian catalogue was less desirable than the “real” book, published by Scalo in 2003, 175 pages, a similar number of plates, also titled Los Alamos. In both cases the images are a selection of photographs from the mid 1960s to mid 1970s, mostly taken on cross-country road trips: curator Walter Hopps drove, Eggleston took photographs.

The Scalo book works very well as a group of photographs, but it represents only a fragment of Eggleston’s original conception, which was to create a 20 volume work containing 2000 pictures — a massively ambitious, and perhaps deliberately unrealistic, enterprise that was duly abandoned. Test prints and unprinted negatives remained in various boxes and archives until 2000 or so, when editor Mark Holborn and Eggleston’s son, William III, made a concerted effort to collect, view, and edit the work, and finally make it available.

The art, photography, and publishing worlds, and indeed Eggleston’s reputation, have moved on so much and so rapidly that Steidl recently published a three-volume edition titled Los Alamos Revisited, which runs to a total of nearly 600 pages. Steidl has also announced publication of an expanded six-volume version of Eggleston’s 1989 book The Democratic Forest, originally just 176 pages, with about 150 images. Jackie Kennedy was the editor at Dutton who bought it and ordered a 20,000 print run for the first edition, which makes it one of Eggleston’s much less collectible books, by which we mean less rare and therefore more affordable, for which I’m very grateful. I picked up a remaindered copy for just $6.95: it still has the sticker on it.

Even the six-volume set will only be a sampling. Holborn, who has been involved with Eggleston’s work since the mid 1980s, wrote in the Financial Times magazine that when he first saw it, “The actual extent of The Democratic Forest was then uncertain, but [Eggleston] estimated there were more than 10,000 photographs so far. In fact, it never had a finale. It was truly endless and there was nothing it could not accommodate, hence the title.”

Well, this is fair enough in one way, and some series are indeed open-ended, but it’s not exactly what books are about, is it? A photography book is in itself a collection of images, similar in some respects to the way that a book of poetry or short stories is a collection, and the best of them share the same qualities. The contents have an internal coherence; the grouping has some parameters. A miscellaneous sampling, set within arbitrary or porous boundaries, is likely to leave us unsatisfied. We need the sense that certain things belong in it, that some things belong elsewhere.

For instance, one small Eggleston gem I own, not much spoken of and still cheaply available, is Horses and Dogs, published by the Smithsonian in 1995, and the images it contains are exactly what the title suggests, photographs featuring hoof and hound, just 26 of them. If the book isn’t considered a highpoint of Eggleston’s career, the images are very fine and unmistakably his, and the collection has a quirky consistency and unity. I’m sure that over the years Eggleston must have taken further photographs of dogs and horses, may have found some old ones in his files, and an expanded edition might well be possible, but nobody seems to be working on that, and those of us who care about these things are perfectly happy with the book as it is: it’s not in need of modification or expansion.

This is not a trivial matter, I think. Supposing you suddenly discovered that James Joyce had written a couple of dozen short stories for Dubliners, ones that hadn’t made their way in, or supposing a stash of 100 Sylvia Plath poems had been found that she’d intended to include in Ariel but for some reason or other hadn’t; well of course you’d want to read those stories and poems, but you wouldn’t exactly be reading Dubliners or Ariel. The original version has an authority that later, amended or amplified versions lack.

The analogy, I know, is imperfect. All photographers shoot far more frames than they can ever realistically show. In the age of digital photography any damn fool can, and evidently does, shoot a couple 100 frames in a day, many of which they may scarcely even look at. This is hardly an option for writers. While it’s common enough for writers to reclaim or reevaluate works they’ve abandoned or even forgotten, no writer looks through his or her files and suddenly finds a couple 100 great unpublished works. Photographers apparently do it all the time, and you can see why that’s possible.

Historically, a photograph, taken in a fraction of a second, has always been essentially complete in itself. It may have been in need of a bit of cropping or retouching, but there was no sense in which a photograph was ever a rough draft or half-finished. Develop it and print it and, for better of worse, the job was done. Of course there have always been exceptions: William Mortensen’s pictures were worked on until they looked more like drawings than photographs. And today when “anything” can be done with Photoshop, the situation has changed out of all recognition: a David LaChapelle digital file when it comes from camera to computer, bears little relation to the finalized, extravagantly worked on image.

¤

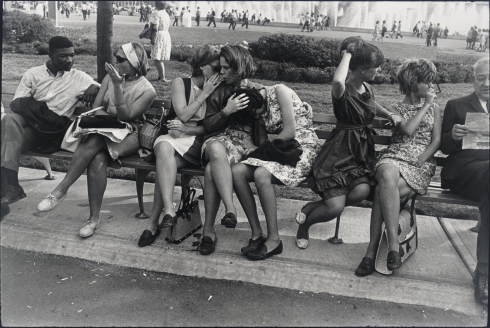

Which inevitably brings us back to Garry Winogrand. There’s currently a huge traveling retrospective of his work (it closed this month at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and will appear in Washington, New York, Paris, and Madrid in due course), displaying 300 of his photographs, a third of which have not been on public display till now. The catalogue delivers even more: 401 plates, 152 of them previously unseen. Exhibition and catalogue describe this latter category of images as “posthumous digital reproductions.” There are good reasons for this curious terminology.

Garry Winogrand, New York World's Fair, 1964

Gelatin silver print; 13 15/16 in. x 11 1/16 in. (35.4 cm x 28.1 cm);

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Dr. L. F. Peede, Jr.;

© The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Toward the end of his life Winogrand, famously, notoriously, shot film like a man who knew his time was running out. In those last years he shot prolifically, obsessively, perhaps manically. As Erin O’Toole writes in the exhibition catalogue, “Winogrand left behind approximately 2,500 rolls of exposed but undeveloped film, and some additional 4,100 rolls that he had processed but not contact printed.” As a zesty headline in Popular Photography put it at the time, “Winogrand leaves One-Third of a Million Unedited Frames Behind.” This is an impressive number even in these days of unrestrained digital shooting, though of course if digital photography had been available to Winogrand, he’d have been spared the trouble and expense of processing, and might have been more inclined to peruse and organize what he’d shot.

The Winogrand situation has created some delicate problems for editors and curators, as well as opportunities for a certain amount of aesthetic posturing. The big question: is it ethical to make a posthumous selection and display of works that the photographer didn’t edit, in many cases didn’t even see? Well, the short answer, for all the agonizing, is that it appears to be just fine: “new” Winogrands keep appearing, and as a fan of the work it’s hard to object to this. Sure, it would have been better if Winogrand had been involved, but circumstances rather got in the way of that. As for whether Winogrand himself would have objected, from what we know of that man, it seems likely he’d have shrugged and said, “Do what you like,” an attitude he displayed toward many editors who used his work.

Great as the Winogrand show is, it does present practical problems. Confronting 300 photographs in a museum would be hard enough at the best of times, but when 100 of them are, so to speak, brand new, the task becomes Herculean: multiple visits are recommended, but really, wouldn’t you rather have the book?

There’s a temptation to play a guessing game: greatest hit or posthumous digital reproduction? Of course the greatest hits are easy to spot — the women in 1960’s dresses walking toward the LAX Theme Building, the legless veteran crawling along the street in Dallas — but without an eidetic memory you might be hard pressed to tell the difference between the new and old images of men in suits walking the streets of Manhattan or people sitting in parked cars.

In some cases, however, there’s no chance of making a mistake. One of the most striking, previously unseen images, which appears on the back of the catalogue and in much of the publicity material, shows a woman lying in the gutter outside a Denny’s in Los Angeles, a Porsche disappearing out of the left hand side of the frame. It’s a strange, cruel, startling image. We’ve seen nothing quite like this before, not even from Winogrand, and yet it remains a thoroughly authentic example of his work. How could he not have wanted it seen?

I’m also very grateful to the SFMOMA catalogue for reprinting a quotation from Winogrand, in which he asserts that photographers are always collectors of a sort. He said:

Understand Walker Evans as a collector of exquisite Americana. Understand the photographer as that. So, if you understand framing in terms of what you want to collect, you include what you want to collect in the frame; you exclude what you don’t want to collect. In other words, the photographer doesn’t have ideas of nice pictures in his head. He’s looking out there and decides what he wants to collect, and lets the look of the picture take care of itself.

¤

As it happens, there is also currently a William Eggleston exhibition on at the Met in New York. Eggleston famously declared that he was “at war with the obvious” and that’s the title of the exhibition. I’ve never actually found Eggleston’s remark all that profound. Is any self-respecting artist not at war with the obvious? Still, it’s a terrific exhibition, the opposite of the Winogrand in some respects, small and perfectly formed, a selection from the Met’s holdings: 14 photographs (dye transfer prints to be strictly accurate) from a portfolio titled 14 Pictures, published in 1974 in a edition of 15, then 15 images that appear in William Eggleston’s Guide, including that half-million dollar tricycle, and six others, for a total of just 35, though the Met website suggests they own at least 50.

William Eggleston, Untitled (Sumner, Mississippi, Cassidy Bayou in Background), 1971

Dye-transfer print; 14 1/2 x 21 7/8 in.;

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (2012.283); © Eggleston Artistic Trust

Again, some of the images are very familiar, some less so, though all have been exhibited or published before. However, one image suddenly popped out at me in a way it never had when I’ve seen it in Guide: yes okay, shoot me, I didn’t say books are always the complete answer. It’s untitled, as so many Egglestons are, but it’s labeled “Huntsville, Alabama” and it shows a fleshy, balding man standing on the tarmac at an airport, a red and white checkered hangar behind him. He seems to be posing willingly enough, though he doesn’t look quite at ease, and beside him is a freestanding wooden sign that reads, “Stay clear of propellers at all times.” Seems like good advice.

There’s no catalogue or book accompanying the exhibition, which is a great disappointment: it would have fitted very nicely into my collection. It would be even better if it were signed.

¤

Geoff Nicholson is a contributing editor to the Los Angeles Review of Books.

LARB Contributor

Geoff Nicholson is a contributing editor to the Los Angeles Review of Books. His books include the novels Bleeding London and The Hollywood Dodo. His latest, The Miranda, is published in October.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!