Francesca Woodman’s Notebook by Francesca Woodman. Silvana Editoriale. 24 pages.

1. PROBLEM SETS

I WOULD PREFER to keep her as I wish to think of her, as an emigrant flitting between worlds, a kind of Franco-Italian woodsprite immured in the charismatic and frail perfection of her minority.

But she is a problem.

She and her figure, which is also her but is not, but which is also a she, and not an it. A problem as in, “How do you solve a problem like Maria,” and a problem as in a problem that is real.

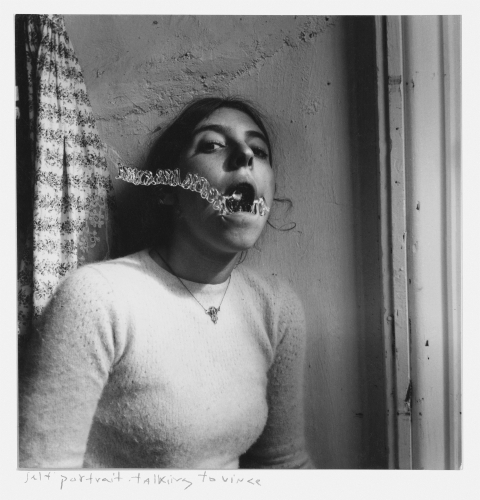

She is a problem because she is a seducer, and I — I mean we — love to be seduced, though we also resent it, and she is a problem because she is a suicide, and suicides are seductive because we all want to die sometimes, and dead young women artists and dead women artists of any age are a problem because it has always been easier for this culture to love their artworks when they, the women, are not alive to interfere with our relations with them, and her precocity was and remains a problem because of its completeness and because precocity is also always resented and dismissed, and she is a problem because it has historically been too easy to praise what is dead and too difficult to nurture what lives, and she is a problem because she is a martyr and ours is a culture addicted to martyrs and martyrology and powered by competition and self-loathing, which leads to the wrong kind of death, and she is a problem because the relation between life and nonlife or the animate and the inanimate is the subject of her photographs and this is too easily mistaken for merely gothy or pre-Raphaelite morbidity or Surrealistish oneirism, and she is a problem because when I look at her pictures I identify with them completely and therefore resent analyzing them as I resent mere praise or critique, and she is a problem because I cannot deny that I identify not only with her images but with real and documented aspects of her despair, and she is a problem because she was not only female but feminine in ways that have caused her work to have been seen as insufficiently critical or insufficiently conscious of its critical potential, and she is a problem because the fact that she appears in her own photographs has caused many to mistake them for self-portraits which they are not, and she is a problem because her photographs do not merely contain elements of nostalgia but they produce nostalgia plastically, though this ache of desire for something somehow lost or past cannot be located in mere mundane time and little resembles her actual times, in a manner analogous to the way Proust’s In Search of Lost Time manufactures its own time, which cannot but trump actual history even as it is generous enough to include it.

And by “she” as I said I mean the figure of her. I mean “Francesca Woodman” the name and everything it has come to signify, and her images and all the sensations they have produced and do produce, I mean every stupid thing and every true thing that has accreted around her aura and I mean the very idea of a figure in time, because time was her medium, not herself. Time itself was her medium. But also within her figure and enclosed within the aura of her figure is the fact that her body was the medium through which she transubstantiated or transfigured ordinary time into actual spirit and because of this there is the feeling she is constantly leaping to her death inside me, as though my spinal column had become the shaft between Manhattan buildings where my own figure, mine too, has always been leaping and falling and dying and has always wanted to smash itself to atoms in this impossible world, and I am confident this feeling and this figure dying forever within me is also beyond common and that maybe you person reading this now have felt or do have such a woman or such a figure leaping to her death inside you. Every woman or every woman artist or every person no matter the gender, every artist but especially every woman who has ever wanted to die or just said she did or had that feeling when she felt so maligned and so misunderstood and so defaced and loathed and ignored that she has either died or not, has died inside herself or has dreamed or longed for an exit like death, has been her and we who have promised ourselves to live have to live with that death and the fact it sometimes looks horrendously attractive although we reject it. The way we have felt cannot be divided from what we think, by which I mean I am committed to admitting the ways I have felt into the ways I must think. It has to be this way right now.

Francesca Woodman, Self-portrait talking to Vince, Providence, Rhode Island, 1975-78, © George and Betty Woodman

Rosalind Krauss’s well-known essay on Francesca Woodman is called “Francesca Woodman: Problem Sets”; it reminds the reader/viewer that some of Woodman’s most famous photographs were in fact meticulously done homework, careful experiments with form, in the context of the pedagogical methods then prevalent at the Rhode Island School of Design, where the young photographer went to school. Krauss decodes her images according to the simple “problems” to which they respond. By reorienting some of Woodman’s most famous pictures as plainly formal and procedural assays, Krauss cools off some of their erotico-mystical heat, their femininity, deftly aligning them with perhaps more respectable, more mathematical, more limpidly conceptual — more masculine? — modes. Krauss manages to show that Woodman’s photographs are less soft than they then may have seemed without going so far as defending or praising them. “Problem Sets” remains useful, because it is still common to hear Woodman’s photographs “feminized,” delegitimized, and dismissed as nothing more than promising student work, unfairly canonized because of the dramatics of her life and death. In any case, and notwithstanding the problems her oeuvre instigates and attracts, it is rare to encounter homework so ecstatically, and so completely realized. But I do not invoke Krauss in order to re-praise Woodman by her lights.

Instead, I hope to expand the field of her problems — the problems within and about her figure — which is not to say that I want to trivialize this figure into that of “a woman with problems” or to turn the critical potential in what I write into the caricature of myself as a woman with problems. Because this essay is being written for the Internet, which everybody knows is an erotic funhouse and a necropolis and a hall of mirrors in which the untrue and the idiotic can never be easily divided from the eternal or the real, not that meaning can ever really be restricted, not anywhere, it would be insufficient for me merely to appreciate or devalue the importance of Francesca Woodman’s photography in the context of recent publications devoted to it. I cannot write as though this were the 1980s and femininity needed to be justified by formality; I likewise cannot write with SFMOMA’s (apposite) reticence around the circumstances of Woodman’s death. This writing will not be protected by a museum nor enclosed within an exhibition catalog, but has to live among infinitely infectious contaminants online, possibly “forever” whatever that means, and insofar as Francesca Woodman and her work are alive because they have become genuinely canonical and undeniably respected, they are even more alive because living people on the Internet are in love with them, and everybody knows the “web” as it used, quaintly, to be called, exists to contain obscenities or excesses of feeling we don’t know what else to do with. An accumulation of problems that cannot be solved, of things from the past and undead things with which we live, in these times, perhaps more intimately than any age has ever lived with what is no longer contemporary, what is no longer biologically alive, and with what has finally become, more than ever, truly timeless.

Writing 31 years since Francesca Woodman’s death, and having come into this world just about when she left it, I see my task — and in several ways my problem — as the problem of reading her figure in time. It has taken me over a year and many sleepless nights to come to know, perhaps, what I felt when I first saw Woodman’s photographs at the SFMOMA retrospective two Novembers ago. I know what I felt when I looked at them, and I know both how I was seduced and how I identified with what seduced me in her pictures. When I first encountered her photographs I had no idea who she was or how she had died, when she had lived or whether she was dead at all. I found it hard to reconcile the way the pictures looked with the dates on the cards beside them and I didn’t want to think about them historically anyway, I just wanted to enter them and I did. I feel lucky that I was innocent of the facts when I found her, and that I could enjoy her pictures without either intellectualizing my delight in them or becoming, as so many have, an apologist for their merits, which have already been intricately and expertly enumerated. As I have said, I just identified. I recognized her photographs as soul-states with which I had intimate experience and I simply welcomed them, with gratitude and pleasure, as true.

2. FIRE

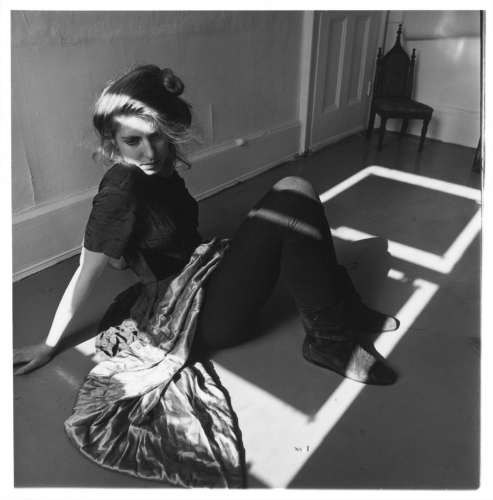

Francesca Woodman was born on April 3, 1958, in Denver, Colorado. Her father and mother, painter George and ceramicist Betty Woodman, maintained a rigorous devotion to art and artmaking; Francesca’s brother likewise became an artist. The family had a home in Antella, Italy, and Francesca’s fluency with Italian language and culture might account at least in part for the sense that in her images, she, or her spirit, never seems quite at home. It is almost as though her photographs were operations by which she could fuse with the spaces that contained her, to triumph over a sense of alienation from them. And also — as though she wished to make visible a certain wild radiance caught flimmering, like some mystic ancient moth drawn to lamplight and about to burn up in it. Her figure does not dwell, it haunts.

Francesca Woodman, Space2, Providence, Rhode Island, 1977, © George and Betty Woodman

Woodman began taking photographs in high school; even her earliest images are mythic in content and ambition, showing her nude, variously merging and inflecting the landscape. She continued her studies at the Rhode Island School of Design, with a productive junior year abroad in Florence, and a postgraduate stint at the MacDowell Colony. She moved to New York intending to earn a living as a fashion photographer while continuing her development as an artist, but she had difficulty finding work in fashion and likewise was unable to connect with collectors or gallerists who respected, much less understood, her photography. She leapt to her death on January 17, 1981, in New York City. There had been a previous suicide attempt, a mounting tendency (expressed in her letters) to agree with the criticisms and dismissals of her work with which she'd become increasingly familiar, a yearning to develop creatively in new directions, a budding — though unappreciated — architectural project exploring the relation between ancient Greek temples and the public bathrooms in New York City, painful ends to unhappy romances, and a rejected application for an NEA grant. Her body of work consists of about 800 prints, some thousand unprinted negatives, sketches and blueprints, as well as notebooks, letters, and related ephemera. Critical and institutional appreciation of her photographs has grown exponentially since her death, and one can only assume that the market for her work and for publications about it has likewise become more and more lucrative. If Francesca Woodman’s Notebook — a chapbook-sized pamphlet facsimile of just one of her many notebooks, sold in an absurdly fussy presentation box for $50 — is any indication of publishers’ optimism about public appetite for any scrap of unseen Woodman, it seems fair to deduce that her corpus has become important not only because authoritative voices have come to praise it, but also because her fame is supported by people who love and are famished for anything offering the faintest whiff of her. Fashion magazines invoke her romance the way they inevitably evoke Egon Schiele or Man Ray like clockwork, art students rhapsodize about her on unnumbered Tumblrs, an elegant and penetrating documentary about her family — of which she is the inevitable star and wound — was recently made. People who teach art bemoan the attraction her work exerts on their students the same way academics (used to?) lament the baleful influence of Sylvia Plath.

3. L’ORIGINE DU MONDE

Francesca Woodman’s corpus has little to do with self-portraiture, though it does comment wryly — and from very early in its already precocious beginnings — upon the deficiency of the very notion of that genre. Self-Portrait at Age 13, which was not included in SFMOMA’s 2011 catalog of her work, rhymes with the first (untitled) image in that exhibition. It dates from the beginning of her time at RISD, when she would have been 18 or 19. In both images, her face is completely obscured by her hair. At age 13, Francesca wears a thick fisherman’s sweater and pants, at RISD, she is nude; in both images her gaze is downcast; at RISD, her legs are spread wide and a mirror is set between them, partly obscuring the hair of her vagina. The gaze of the camera is deflected by a mirror and the gaze of Francesca is hidden by hair, as genitals are; her legs are open, signifying the frank disclosure that there is absolutely nothing to see here. Woodman’s oeuvre opens, as did SFMOMA’s exhibition, with a brilliant deflection of the merely psychological or merely documentary aspects of what can nevertheless be taxonomized as self-portraiture. First the face is veiled by hair, and later, the genitals too are veiled — indeed protected — by the deflecting light of a mirror: this figure will neither give her face nor her crotch to her own camera, to which she nevertheless gives more. It is as though, from the start, she set out to trump photography’s merely documentary aspect, or to use the medium to document a kind of truth that responds to a wholly other order. To borrow a phrase from John Ashbery, she protects what she advertises. To perceive in oneself — let alone in another, or in an image — an origine du monde means to confront what appears to be a disclosure and is in fact infinitely veiled and impossible to lay bare. From the very start, Woodman seems engaged in a game of restoring to industrial culture the sense that despite the fact that everything can now be shown, something divine nevertheless transpires in a person that need never merely give itself just because it can. Likewise, she insists, like Lacan, that there is and can be no sexual relation — at least not with her images. Period. Which is to say, however undeniable (and who would presume to deny them), her erotics belong fundamentally to themselves; no matter what they give over of themselves, they keep the better part of their mystery to themselves. A good control for this is a Google image search for photographs by others in which Woodman appears as the model. In many — if not most — of these pictures, her figure radiates none of the mystery or electric fugacity and a lot less of the beauty it exudes in the photographs in which she appears that she made herself. If you weren’t reading this online and if the times weren’t these, it might go without saying that in spite of the volcanic sexuality her photographs exude, they never become pornographic, much less narcissistic. But because part of what the Internet means is infinite obscenity, it has become important to distinguish a certain kind of image from performances of disclosure to which we have become accustomed, not only in visual culture, but in the ways we read and write.

4. IN BOCCA AL LUPO

The name Francesca would seem to be Italian for “French lady,” or Frenchesque, or perhaps even a free, or freeish, girl. Like an earthier transposition of some Parisian evening gown, like something luxurious and imported into a place slightly more sanguine, and differently voluptuous. The name Francesca likewise bears the French-accented mark of the Surrealist bookshop in Rome called Maldoror, which gave the photographer her first solo show, one of whose proprietors she lovingly addressed, in her letters, as “Ducasse.”

In any case, photography itself, like Lautréamont, originated in France. The medium would develop, within Francesca Woodman, in Italy — both throughout her childhood at her family’s home, and during her junior year abroad in Rome. Insofar as her photographic influences seem to stretch from Daguerre to the Surrealists, especially Claude Cahun and Hans Bellmer and Man Ray, while also invoking the sculpture of classical antiquity, Flemish still lives, and the occasional experiments with portraiture by way of Cézanne or Matisse — Francesca Woodman can be said to have practiced, throughout her short life, a kind of photography alla francese.

The conjunction of a curvaceous, pre-Raphaelite spectrality crossed with French Surrealism, and decayed into post-fascist Rome — echoing through the crumbling interiors and cemeteries where she liked to work in the US — all this is contained within her first name alone.

And then there is the patronymic, as masculine as her first name is not, as frank as her first name is filigreed, as arboreal as her first name seems urban, right down to its rhythm — two syllables for two legs walking through the woods, against the sophisticated waltz at the other end of her signature. Both the wood and the man, or the woodsman inside her, are also clearly visible in her photographs, from the pictures in which her body fuses with the roots of a tree plunged into water or passes ghostlike through headstones to the images shot in decaying interiors in which her figure writhes or flickers creature-like through burning bands of sunlight or melts into shadows or merges with walls or simply shimmies up a doorframe to fuck the wainscoting, as though to make the walls come alive. Consider the woodsman from Snow White: the evil Queen orders him to find and kill her stepdaughter, and commands him to return with Snow White’s heart in a box. But when the woodsman finds the girl, among her dwarf and animal friends, he is so overcome by her goodness and purity that he kills a deer instead, and delivers the beast’s heart to the Queen, whose magic mirror of course instantly reveals his deception. In many ways, the woodsman stands for what is — and will always remain — good and simple in the world. He is the salt of the earth, which neither evolves nor becomes degraded, in spite of the most intricate depredations of societal unfolding. The woodsman represents a certain promise in the slow and steady goodness of life itself, or of the almost animal sense inside us that every once in a while is very, very clear about the difference between Good and Bad. The woodsman is neither subtle nor is he complex, and he manages to hold fast to the good in the world even though his employer is evil. In many ways, the other members of the Woodman family, if they can be known at all via the documentary named for them, seem largely to incarnate this principle of the woodsman entirely: the pursuit of art sutures them to life, not death; the sometimes strange work of mourning — with the twinges of envy or repression that attend it — inflecting what seems in them a sort of simplicity; a goodness. They pursue what is for them The Good (artmaking) with dogged and committed simplicity, slowly but surely earning for themselves the respect of their peers and the appreciation of collectors, all the while maintaining their family with thrift and earthy good sense.

The way Francesca was a Woodman was in many respects very like the way her parents and brother are Woodmans, but there is an added dimension to her particular earthiness. In her photographs, flashes of her caryatid flesh disperse wraithlike into crumbling walls and fields of mud; a sweet solid girl tests out the space and limits of her own skin. The earthy “naturalness” she radiates in some pictures — the solidity and health of her body, her armpit hair and biceps, the very fact of her comfort photographing herself nude. Like the she-wolf who suckled the founders of Rome, even Woodman’s most refined experiments with light, geometry, and form are nourished on — even originated by — something wild, ferociously driven, utterly female, and dangerous.

The signature of these two fields of spirit — first name and last name — does not merely characterize the pictures she made. The figurations within her images have become engraved upon her name for all time, just as they were announced by her name before she ever became what she would become in life, and then in death. We might say that her life, like ours, was simply a question of living up to the name, fame or no fame, with which she entered the world at birth. In thinking of her this way, we don’t remove any of the prestige that has accreted around what she made, but rather, we attempt to apprehend this prestige from a healthier vantage than American culture’s lurid and often idiot attachment to haloes of death.

Romans have a special way of wishing each other good luck, which invokes their city’s very origins, and effectively tells them to fuck off: In bocca al lupo, one person will say — In the wolf’s mouth. Crepi! answers the other: To hell with the wolf — let it die.

5. VANITAS

To judge from the letters, postcards, and ephemera gathered in the publisher AGMA’s recent compilation of Woodman’s time in Rome — Francesca Woodman: Photographs 1977—1981 — an affectionate constellation of young artists and friends, both expatriate and Italian, gathered around the Maldoror bookshop, in a kind of parallel to what seems to have been going on concurrently in New York: young artists of all genres were forging their styles out of French symbolism, English decadence, Dada, and Surrealism. It would be difficult to call what she was doing punk exactly, but it would also be disingenuous to ignore that rock bands in New York were suffused with the filth, rebellion, and scrofulous splendor of France’s 19th-century malaise. Francesca Woodman often resembles a kind of supercharged, spiritualized reincarnation of the eternal artist’s model immured in her decaying era — unwashed whores and slums memorialized with such tenderness and tact by Eugène Atget. But Francesca Woodman is of course her own model, so her invocations of some of early photography’s greatest hits become witty riffs on the question of whether modernism even took place — and if it did, for some of her more cinematic images evoke it, whether an hourglass figure like hers can ever not make whoever gazes upon it think of time — in particular, time past. It is in this way that her photographs begin to become literary, often exuding both a morose confinement and a wild, elemental drive toward escape. There is a kind of quiver between Victorian sexual frustration and the more bookish malaise of the brilliant and liberated modernist woman, or the cinematic banality of depression at study abroad, the plight of the gifted bluestocking who nevertheless has to work as a secretary or nude model to get by while talent alone is good enough for the men who are her peers, but no matter what she does or refuses to do, ends up feeling like a whore. If one can judge from the letters she wrote toward the end of her life, (which will be discussed below), reading the wry and melancholy romance of her photographs through them, Francesca Woodman’s two years in New York were as miserably modern as a Jean Rhys novel.

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, New York, 1979-80, © George and Betty Woodman

Woodman’s photographs do not merely evoke her medium’s earlier days, nor is their sole ambition to reproduce the feel, as in well-styled magazine photography, of antiques. Nostalgia is a complicated thing to deal with critically, especially because it tends to be seen as a rapturous embrace of “the fathomless abyss of time” — to borrow a line from John Wieners — when men do it, whereas in women’s hands a formal relation to the past, even a melancholy mode, imperils the seriousness with which her work might be taken — after all, such things can easily veer into the territory of period pieces on Lifetime television, a kind of suspect and overly-fashion-conscious affectedness. In one sense, it is true that nothing could be more bourgeois than the kind of ache period pieces are designed to evoke, but in another sense, to deny our sentimental apparatus as having been forged upon the bulwarks of capital, what it kills, and its dream machines, is simply to lay claim to an immunity to the past that cannot exist — and never has. Variously alert or sensitive souls have been escaping the hells of their respective ages into whatever they could forge of an imagined past since well before the Renaissance drove the brightest minds of the age into ecstatic communion with ancient Greece and Rome. From the banality of Emma Bovary’s shopaholic binges to Proust’s fascination both with the medieval and with whatever, socially, would exclude him. I can neither deny nor avoid an attempt at reading Francesca’s style of backward-looking romance (and perhaps embedded within all romantic sensations are creepy, creeping nostalgias) — nor can I see this romance as anything but an absolute affirmation both of the force of depicting soul-states in space, and as an indictment of the blindness; the deadening effects of an at least somewhat dead world that failed to see as richly as Francesca Woodman herself could. Not even to imagine — simply to see, to perceive within the present, within the real, much more than what was merely present. And yet her pictures are documentary, insofar as they depict, with great intensity and charm, what it feels like (for a girl I guess, but not necessarily only); what longing feels like, what play feels like, not so much what it looks like to be alive, but what it feels like.

Francesca Woodman, House #4, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976, © George and Betty Woodman

Francesca Woodman seems to have been fated to carry some of the formal and political investigations of her time back both to the origins of photography itself, and to more ancient — and of course transpersonal, and politically problematic — aspects of divine femininity that, however common and dismissible they might still seem, especially under certain light, have always haunted human image-making. In AGMA’s volume of letters and ephemera, we discover that she was a spirited and affectionate correspondent, filling her letters with florid descriptions — florid like her first name — of rather simple daily affairs like eating and drinking, which suggest the more masculine aspect of her patronymic. A process of enchanting — and also of haunting — mundane affairs and relatable soul-states is likewise always at work in her images. Ghostly bodies merge with the decaying walls that enclose them, a blurred girl ducks translucently behind an old mantelpiece; peeling wallpaper becomes material for a sepulchral fan-dance that manages both a gothic satire of burlesque and a witty intersection of youth and age, of the animate with the inanimate — or to put it more bluntly, of sex and death.

6. “IN THE PINK AND LACY FASHION”

Francesca Woodman wrote that she found herself to be, unlike her down-to-earth ceramicist mother, “very feminine in the pink and lacy fashion.” Her letters occasionally refer to her “bratty” tendencies, and whenever emotional havoc is (euphonically) mentioned, she tends to blame herself for it, whether or not her flirtatiousness, ambition, charm, or sense of her own specialness really were the cause of romantic upheaval or rough patches in friendships. Her letters are so suffused with creaturely sweetness that one wonders at some of the vaster and more terrible forces of nature that could sometimes pass through her. Like some of her photographs, her letters are girlishly funny, charged with erotic promise, putting both expansive emotional generosity and an almost prissy Victorian vagueness on display in nearly the same breath. They feel charming and fanciful, they do put on airs, and yet they are strangely humble in the grandiloquence of their intimacies, in the way of certain imaginative girls — brilliant, evasive, gushy, flirtatious, and oddly chaste in that special style that comes naturally to some. The letters, like many of the photographs, admit as much self-deprecating humor, and as much charm, as they let in banality, simplicity, the occasional ugliness, and courage. This femininity — this girlishness — or these femininities, these girlishnesses — caused her trouble.

In a letter to the feminist artist Suzanne Santoro, which Woodman typed on June 18, 1980, seven months and a day before her suicide, she writes with a kind of desperate seriousness, both of recent creative developments in her work, and of the professional misery against which she was struggling:

I wanted to talk about lofty and calm things, since my life is niether [sic], and also to get away from the very intuitive personal pieces that have carahterized [sic] my work in reacent [sic] years. This fall 3 seperate [sic] art dealers insinuated in various ways that to understand my work they would have to sleep with me and the idea that my pieces seems to evoke that kind of response revolts me is diametrically opposed to what I was trying to express. Have you ever had similar problems?

If we can judge by the unfolding of these sentences, Woodman’s desperation to escape the “intuitive” and the “personal” in her work seems to come directly out of those three revolting experiences with art dealers.

Now that Woodman is dead, anybody is free to fantasize about her (“her”), unencumbered by the annoying intrusion of her actual existence as separate from the work itself. This is not to negate the fact that a steadily growing chorus of critical voices has praised and parsed her oeuvre with great care, even reverence. SFMOMA’s catalog affirms a great respect for Woodman’s technical mastery and privileges her more serene and classical photographs over some of the wilder compositions involving nature and the occult, not to mention fashion. The catalog likewise cools off some of the frankly scandalous and idiotic things that have been said in connection to Woodman’s work (Philippe Sollers being perhaps the most stupendously chauvinist commentator of them all) by stitching them into an essay that is, basically, a compendium or précis of some of the darndest things that have been said about Francesca Woodman, for better and worse, since her death. And, as noted above, the SFMOMA catalog likewise tactfully refrains from indicating the method by which Francesca Woodman ended her life —perhaps implicitly acknowledging suicide’s distorting power on the public’s relation to a given artist or works — while simultaneously rendering “francesca woodman how did she kill herself” a popular Google search term.

Even though I cannot be sorry that certain dead visionary women have attained in death the adoration they deserved in life — I’ve already mentioned Sylvia Plath, or Anne Frank or Virginia Woolf (Marilyn Monroe? Amy Winehouse?) — there is also something creepily avuncular and overheated about the culture industry “cumming” all over what it either never honestly bothered to nourish or insisted on taking only exactly the way it wanted to. Female commentators, including the brilliant ones, are often beset by the problem of (over)identification when they write about such figures, while male commentators cannot seem to give praise or produce readings, however just, without betraying a kind of respectful arousal (or aroused respect?) rendering themselves the somewhat abashedly horny liberal uncles of the world, free to jizz into history on the figure of the actual woman whose intention it was decidedly not, via her photographs, to merely physically seduce them.

And at the same time I suppose there is nothing wrong with being in love with the dead, with making a dead figure into the repository of mystical lust. Maybe that is what romance really is — a kind of organ that produces a story of desire in us, to which we all — beyond the simplistic gender binary I’ve just erected — have a right.

7. RITUALS IN TRANSFIGURED TIME

What I do in my films is very … oh, I think very distinctively … I think they are the films of a woman, and I think that their characteristic time quality is the time quality of a woman. I think that the strength of men is their great sense of immediacy. They are a now creature and a woman has strength to wait because she’s had to wait. She has to wait nine months for the concept of a child. Time is built into her body in the sense of becomingness. And she sees everything in terms of it being in the stage of becoming. She raises a child knowing not what it is at any moment but seeing always the person that it will become. Her whole life from her very beginning — it’s built into her — a sense of becoming. Now, in any time form, this is a very important sense. I think that my films, putting as much stress as they do upon the constant metamorphosis — one image is always becoming another. That is, it is what is happening that is important in my films, not what is at any moment. This is a woman’s time sense and I think it happens more in my films than in almost anyone else’s.

— Maya Deren

Unlike the photographs we take of ourselves today, whether using our computers or smartphones, and whether or not we take these images of ourselves so seriously as to consider them self-portraiture, much less any other form of art, time itself went into Francesca Woodman’s pictures — not the kind of time spent creating effects after the photograph was taken, and not in particular the time spent making magic in the darkroom, a dimension of image-making that did not interest her beyond the most straightforward processing of her negatives. The “timeless time,” to borrow a phrase from her contemporary Nico, inside Woodman’s photographs, was the time it took to select the elements for their semi-improvisatory making, plus the time it took to take them, behind which was, of course, each contour of every single thing she ever saw or did in her life, as is true for all artists. And yet the sense her photographs exude, of having captured a soul-state somehow live, like a bug in amber, is rare. It may be that making images that evoke and isolate complex inner states is itself an antique thing even to want to do.

The tendency in these times seems, both within and without the domain of art, is to infer inner states or underlying realities by examining the outward evidence. To put this another way, the degree to which surveillance culture has shaped the way we see and conceptualize those aspects of lived reality that transcend or escape mere visibility should not be underestimated. In the same way that looking at pornography engenders arousal inside the body looking at it, image culture tends either to simply show what is there or to depict exactly what it imagines in order to engender effect in the viewer as calculated consequence or inference. Zones suffused with the more classically uncanny interplay between illusion and document, between what can be seen and what can only be sensed, are not easily found. Zones whose substance is time itself, but which are also somehow detached from time.

Francesca Woodman’s photographs don’t feel like the famous photographs of the late 1970s. They don’t even feel like the 1970s, not that I could possibly really know, since I was never there. And yet their magnetic power — their ability to suck the viewer into the flashes of eternity they capture — accounts for their tremendous, and ever-increasing, popularity. Insofar as, in certain ways, there is no such thing as innovation when it comes to what it feels like to be human, the timelessness and accuracy — even the universality — of Woodman’s pictures is the most important thing about them.

Her images feel strangely protected, not only from her own times, but from ours. Despite the many influences she had in common with some of the East Village’s more on-trend heroines, Woodman either would not or could not transpose her sexuality, or her (hardly unpopular) influences into the more overtly punk rock precincts of pleasure and pain. She did not resemble the stars or sick muses I associate with those times: I’m thinking of the glamorous dissolution in Nan Goldin pictures, of the brilliant screenwriting and acting of East Village junkie Zoe Lund, the relatedly voracious child genius Lydia Lunch, or the absolute sex beyond gender of Patti Smith. I’m even picturing Woodman’s neighbor on East 12th Street, Richard Hell, in all his photogenic malaise two or three buildings away. Madonna, Basquiat, Downtown 81 — all of these people lived in similar hellholes, if not the same world. And yet Francesca Woodman seems to have existed utterly apart from them. I wonder what it was like for her to get dumped, to type the earnest and desperate letters of her last months, to try to work, fall apart around her shit jobs, to shop for slightly less Victorian clothes, to try to seduce herself into becoming someone new, which is a thing, which is a thing you do to yourself in New York and when it works it works and when it doesn’t. I wonder about the parties and whether she ever went to them. Whether everyone felt as lonely and alien as she might have, but seduced themselves into their times while she could only magic herself out of them in the images she made. I think about her brilliant architecture project called Temple, about Greco-Roman flourishes in the public bathrooms of New York, about whatever remained of the notion of an imperial sacred space that was truly open to anyone having become the grandeur, filth, banality, and sainted grace of public toilets (which incidentally no longer exist). I wonder whether anyone she knew saw what was inside her the way she did, and whether she felt it was fundamentally an intellectual failure that she couldn’t figure out how to make anybody get her, just get what she was about, which could have been why she tried to change, despaired of changing, got tired of trying, and died.

There is a way I feel, or simply want to feel, that she wasn’t made for the city. The City, as in New York. There is so much less melancholy in the merging of her figure with a field of mud or the roots of a giant tree, as in images dating from her high school days, than in the sense of caged wildlife that her later pictures radiate. I prefer the child raised by wolves, the genius daughter of the Venus of Willendorf, to the sadder and perhaps more “relatable” figure she cuts when she gets a bit older — a brilliant and misunderstood young woman trying to make it and failing, a brilliant young woman in New York looking for love and not finding it. The crumbling interiors in which she liked to work evoke a life in the lap of Miss Havisham. Which is to say, they capture the soul-state of a free spirit trapped in embittered and forgotten interiors whose long-decayed romances and salad days parallel the (no-less-miserable-to-endure-because-deserved) decline and sexual misery of Occidental culture. The suggestion that her work is too “archetypically feminine” to be considered feminist critique should be trashed.

8. IN SEARCH OF LOST TIME

In a letter to Giuseppe Gallo, one of the owners of the Maldoror bookshop, dated January 4, 1980, Francesca Woodman writes that while recovering from a prolonged sickness, she read “the complete works of Proust, which inspired me a lot. I’d really like to create a work of art like that, rooted in and linked to everyday life, but addressing questions of great scope.”

“I got really sick,” she writes, euphemizing or candidly describing — depending on your perspective — an anguished depression and her first suicide attempt, which, at least rhetorically, within the sphere of this particular letter, issues out of her attempt to come to grips with the criticism that her work was too self-involved:

[Y]ou remember that my work used to be very personal, feminine, too much to do with myself and I wanted to create a bit of distance and also to do something with a more universal significance. Then this fall I was really unwell and I let myself go, I couldn’t sleep etc etc and I got really sick, I couldn’t understand what was happening, you know I’m not the delicate type at all. I ended up in hospital and then at my mom’s house to recover. It wasn’t all bad because I had the time to read the complete works of Proust.

Her convalescence wasn’t all bad because it gave her time. Which she had not, perhaps, realized before was something she already had, or which had not formerly been something she wanted. Few of us want time when we are 22. I wanted everything but it. The forsaken ancientness that can fill a young woman whose fame, for whatever reason, has failed to measure up to her gifts and ambition — shows in Francesca's eyes in her late pictures. It's as though she can no longer enchant herself, or that the soul looking out no longer knows what or where it is.

And yet it seems, at least from here in 2013, that she had already made the corpus to which her experience of Proust caused her to aspire. Woodman’s photographs produce something of Nico’s "timeless time," which I guess will only become easier to enter the further we get from 1981.

¤

LARB Contributor

Ariana Reines is a poet, playwright, and translator. She was born in Salem, Massachusetts; right now she lives in Queens.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Ballad Continues: On Nan Goldin

On her classic 'The Ballad of Sexual Dependency'

C’est Pas Moi: On Kate Zambreno’s “Heroines”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!