At Least He Reached Consummation: On Frank Bidart’s “Against Silence”

Nathan Blansett considers “Against Silence” by Frank Bidart.

By Nathan BlansettJanuary 27, 2022

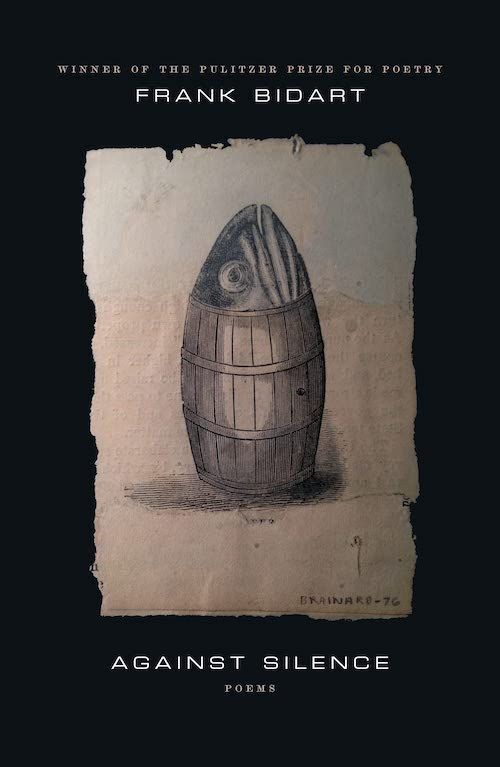

Against Silence by Frank Bidart. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 80 pages.

FRANK BIDART left Bakersfield in 1962 to attend Harvard and found himself the student-cum-confidant of Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell. Such inimitable voices, for any other fledgling poet, ought to prove annihilative (“Life to him,” said Keats of Milton, “would be death to me”). But the young Frank Bidart, preternaturally self-possessed, knew that his poems, if they were to be his, could not model, for example, the “brilliantly concrete world” of Life Studies, Lowell’s enormous achievement. Bidart’s poems demanded he dramatize his own “attempts to organize and order” his life, as well as his “failures” to do so. “That,” he says in an interview, “was my subject”: emphasis, as always, his.

For Bidart, looking different was pursuant to sounding different. Dynamic, radical enjambment; unconventional typography; expressive capitalization: his poems look, emphatically, like no one else’s. Yet his vers libre intoxicates a reader as much as any traditional prosodic shape: read Bidart aloud and hear how thoroughly a human voice can be “fastened” onto the page.

This task of transcription has sustained Bidart’s practice from the beginning. Early collections like Golden State (1973) and The Book of the Body (1977) demonstrate command of dramatic monologue; here is the unforgettable anorexic “Ellen West”:

— My doctors tell me I must give up

this ideal;

but I

WILL NOT … cannot.

Though gossip abounds that Maria Callas has “swallowed a tapeworm,” our speaker knows,

of course she hadn’t.

The tapeworm

was her soul …

— How her soul, uncompromising,

insatiable,

must have loved eating the flesh from her bones,

revealing this extraordinarily

mercurial; fragile; masterly creature …

Few poets have written a book as mercurial and masterly as Desire (1997), Bidart’s mid-career masterpiece, where a voice chants,

Oh yeah Oh yeah Oh yeah Oh yeah Oh yeah

until, as if in darkness he craved the sun, at least he reached

consummation.

— Until telling those who swarm around him begins again

(we are the wheel to which we are bound).

Readers of Bidart now have Against Silence: his 11th collection, and the first published since Half-light: Collected Poems 1965–2016 garnered him an overdue National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize.

The voice of Against Silence is raised in lament. The second poem locates us “At the Shore”:

The shore is in mourning. It mourns what it must soon

see, the sea

rising —

implacable, drowning chunks of the intelligible, familiar world.

Imminent, perhaps irrevocable ecological catastrophe is juxtaposed against a childhood memory of the speaker in his parents’ car, simultaneously “protected” and

Unprotected. Phantasmagoric enormous

tumbleweeds in the empty

landscape rolled endlessly outside the speeding car.

A force beyond climate disaster surges and further threatens these pages. “Mourning What We Thought We Were” dates itself to a month after the 2016 presidential election: “We were born into an amazing experiment. // At least we thought we were,” the poem begins. The speaker dreads that “[w]hite supremacists, once again in / America, are acceptable, respectable,” which triggers an acknowledgment of familial racist complicity: “My grandmother’s fury when, at the age of seven or / eight, I had eaten at the home of a black friend.” Notably, this poem appropriates and rewrites an earlier poem by Bidart, “Race,” collected in Metaphysical Dog (2013):

Disconsolate to learn her

seven-year-old grandson

spent the afternoon visiting the house —

had entered, had

eaten at the house —

of his new black friend, her fury

the coward grandson sixty-five years

later cannot from his nerves erase.

“Race” mostly arraigns Bidart’s grandmother and “the dead world / she […] obeyed,” whereas “Mourning What We Thought We Were” saliently indicts the American plural. Still, these are lines we already know. This labor of refinement and clarification, while understandable and noble, does hamper some of the first section’s momentum.

“The Fifth Hour of the Night,” which closes the book’s first section, proves energizing for Against Silence and for Bidart’s “Hour of the Night” series. This series of poems proceeds from ancient Egyptian myth: the sun, before rising, must pass, during the 12 hours of the night, through the 12 gates of the underworld. Each enigmatic “Hour of the Night” has treaded new thematic territory and made new music. “The Fifth Hour of the Night,” mostly rent of classical or mythological or historical framing, more explicitly autobiographical, frequently digressive, features some of the most exhilarating verse in this book:

Aging men want to live inside sharp desire again before they die.

The terrible law of desire is that what quickens desire is what is DIFFERENT.

Thirst for the mirror on which is written: Fuck me like the whore I am.

Thirst for erasing the pretense of love.

“Eating today, however / satisfying,” Bidart is keen to remind, “frees no creature from having to eat / tomorrow.” Frank Bidart is 82 years old; the voice “fastened” onto the page in Against Silence is pitched lower than ever before. “Who knows how long this will go on?—” asks the poet, the poet who once hypnotically expressed in “The Second Hour of the Night” (1997) that “no creature is free to choose what / allows it its most powerful, and most secret, release,” who now plaintively confides,

(secretly, how relieved we are to find, yet again, for

each of us, what generates

lust—).

Many of the poems in the book’s second section have an insomniac’s strange clarity. “Last night after midnight, or would that be today? unable to sleep,” one poem both begins and ends. The nocturnal speaker, watching the “restored yet forever still- / butchered” Judy Garland version of A Star Is Born, dolefully recalls that, “at fifteen, in 1954,”

I could not

persuade my mother and step-father to drive

a hundred and twelve miles from Bakersfield to Hollywood

to see

in my lifetime I

cannot ever see.

As always, Bidart turns his gaze back toward his parents, especially the art he has made from his anguished relationship with them:

It was all a dialogue with flesh. Every

moment. Dialogue

with what you were not.

[…] I blamed

my mother and grandmother and father

as if they were

souls, not flesh —

The proximity of the expiration of flesh has made for some of the most affecting poems here, like “On My Seventy-Eighth,” whose alternating long and short lines veer between vigorous bel canto and solemn sotto voce:

Those who torment because you know you

loved them

refuse to remain buried. Is anything ever forgotten,

actually forgiven?

Shovel in hand, I saw how little I had

known you.

The poet ought to move us, says Wallace Stevens, “from the chromatic to the clear, from the unknown to the known.” Only by revealing the complexity of our desires may we even possibly achieve the dream of an immortal art. Against Silence memorably sees our greatest living poet of the flesh expressing and assessing fear of flesh’s end, of dispensability, of desire’s flame dimming to mere flicker.

Bidart, when fearful, is ever careful to remind himself what his poems have long reminded us: “Come, / give up silence,” he writes. The poet and reader keen to censor, ironize, or infantilize their own desires will find in the work of Frank Bidart a half-century-long rebuttal.

¤

LARB Contributor

Nathan Blansett’s recent poems appear in Ploughshares, New Criterion, American Chordata, and The Southern Review.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Joy of the Gamble: A Conversation with David Lehman

Aspen Matis in conversation with poet David Lehman, whose newest book is “The Morning Line.”

A Lifetime of Song: On Rita Dove’s “Playlist for the Apocalypse”

Teow Lim Goh considers “Playlist for the Apocalypse” by Rita Dove.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!